Colloque Vol 65.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catholic Educational Exhibit Final Report, World's Columbian

- I Compliments of Brother /Tfcaurelian, f, S. C. SECRETARY AND HANAGER i Seal of the Catholic Educational Exhibit, World's Columbian Exposition, 1893. llpy ' iiiiMiF11 iffljy -JlitfttlliS.. 1 mm II i| lili De La Salle Institute, Chicago, III. Headquarters Catholic Educational Exhibit, World's Fair, 1S93. (/ FINAL REPORT. Catholic Educational Exhibit World's Columbian Exposition Ctucaofo, 1893 BY BROTHER MAURELIAN F. S. C, Secretary and Manager^ TO RIGHT REVEREND J. L. SPALDING, D. D., Bishop of Peoria and __-»- President Catholic Educational ExJiibit^ WopIgT^ F^&ip, i8qt I 3 I— DC X 5 a a 02 < cc * 5 P3 2 <1 S w ^ a o X h c «! CD*" to u 3* a H a a ffi 5 h a l_l a o o a a £ 00 B M a o o w a J S"l I w <5 K H h 5 s CO 1=3 s ^2 o a" S 13 < £ a fe O NI — o X r , o a ' X 1 a % a 3 a pl. W o >» Oh Q ^ X H a - o a~ W oo it '3 <»" oa a? w a fc b H o £ a o i-j o a a- < o a Pho S a a X X < 2 a 3 D a a o o a hJ o -^ -< O O w P J tf O - -n>)"i: i i'H-K'i4ui^)i>»-iii^H;M^ m^^r^iw,r^w^ ^-Trww¥r^^^ni^T3r^ -i* 3 Introduction Letter from Rig-lit Reverend J. Ij. Spalding-, D. D., Bishop of Peoria, and President of the Catholic Educational Exhibit, to Brother Maurelian, Secretary and Manag-er. -

Cni January 8

January 8, 2021 Image of the day - Epiphany, Henry Clarke [email protected] Page 1 January 8, 2021 New stamp to mark 150 years since disestablishment of the C of I (L-R) Bishop of Cork, Cloyne and Ross, The Right Reverend Dr. Paul Colton and Archbishop of Dublin & Glendalough The Most Revd Michael Jackson reviewing the new stamp last month. A stunning image of the sun, moon and the stars reflecting in a stained glass church panel will adorn a new series of stamps unveiled by An Post today to mark the 150th anniversary of the Disestablishment of the Church of Ireland. The new national €1 stamp bears the image of the iconic panel that graces the window of the Cathedral of Saint Fin Barr in Cork city. Alison Bray reports in Independent.ie. [email protected] Page 2 January 8, 2021 The new series, designed by Dublin’s Vermillion Design company, pays homage to the Church of Ireland’s break from the Church of England and the State when it was officially disestablished on January 1, 1871. The act, along with the introduction of Home Rule and the Land Act under then British Prime Minister William Gladstone was among his efforts to deal with the so-called ‘Irish question’ while removing the status of a State church “that had commanded the allegiance of only a minority of the population,” according to An Post. Commemorative postage The Most Revd Dr Michael Jackson, Archbishop of Dublin and Bishop of Glendalough, gave his blessing to the new series. He said: "Disestablishment has enabled the Church of Ireland to be free to shape its own future. -

Salina Is Named See City in Northwestern Kansas DENVER

I 'Member of Awilt Bureau of ClreuXatiora Salina Is Named See City in Northwestern Kansas —----------------------------- - 4- + .+. + Content* Copyrighted by the'Catholic Press Society, Inc. 1945— Permission to Reproduce, Except on Articles Otherwise Marked, Given After 12 M. Friday Following Issue Salina, be. Supplants Concordia Church of Sacred Heart I;;. dral of the diocese in the transfer o f the seat o f the diocese to that rily from Concordia in a change announced this week by Bishop As Diocesan Center; Frank A. Thill. The Rt. Rev. Monsignor Richard Daly, V.G., present DENVER CATHOLIC pastor. o f Sacred Heart church, becomes the rector o f the new Ca thedral. The transfer of the diocesan headquarters from Concordia to Salina was deemed necessary, chiefly because o f the more con Decree Bead Mar. 12 venient idlation o f the new headquarters. Salina is considerably larger than Concordia. The Bishop hat announced that all official Pontifical Holy Week services will be conducted in tbe Salina Cathe Transfer Authorized by Pius XII Dec. 23,1944, REG ISTER dral for the first lime this year. Reveals Bishop Frank A . Thill; No The National Catholic Welfare Conference News Service Supplies The Denver CathoUc Register. We Have Also the International News Service (Wire and Mail), a Large Special Service, Seven SmaUer Changes Made in Officials Services, Photo Features, and Wide World Photos. (3 cents per copy) Salina, Kans.—At a meeting of the Diocesan Consultors VOL. XL. No. 28. DENVER, COLO., THURSDAY, MARCH 15, 1945. $1 PER YEAR held in Sacred Heart church March 12, Bishop Frank A. -

John L. Burke Papers

Leabharlann Naisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 63 JOHN L. BURKE PAPERS (Mss 34,246-34,249; 36,100-36,125) ACC. Nos. 4829, 5135, 5258, 5305 INTRODUCTION The papers of John Leo Burke (1888-1959) were donated to the National Library of Ireland by his daughter Miss Ann Burke. The major part of this Collection was received in two sections in September 1997 and January 2000 (Accession 5135). Other material was donated as follows: September 1994 (Accession 4829); June 1998 (Accession 5258) and November 1998 (Accession 5305). These various accruals have been consolidated in this List. The Collection also includes a biographical note on John Leo Burke by Robert Tracy (MS 36,125(4)). LETTERS TO JOHN L. BURKE MS 36,100(1) Actors’ Church Union. Irish Branch 1953 Oct.: Circular in support of the Irish Branch. Autograph signature of Lennox Robinson. 1 printed item. MS 36,100(2) Allgood, Sara 1923 Dec. 12: Thanking JLB for sending story; Abbey production of T.C. Murray’s Birthright. 1 sheet + cover. MS 36,100(3) Bodkin, Thomas 1959 June 16: Gift of print for John Costello. Portrait of Joyce. Unhappy about conditions at National Gallery – “God save us all from the machinations of incompetence.” 1 sheet. MS 36,100(4) Colum, Padraic 1949 Sept. 6: Thanking JLB for photograph of Joyce. Good quality of articles in The Shanachie. “Joyce used to frequent Aux Trianons, opposite Gare Montparnasse. The food is good …”. 1 sheet + cover. MS 36,100(5-6) Cosgrave, W. T. 2 items: Undated: Christmas card. -

Ireland and the Anglo-Norman Church : A

Cornell University Library BR794.S87 A5 1892 Ireland and the Anglo-Norman church : a 3 1924 029 246 829 olln B9, SB7 AS IRELAND AND THE ANGLO-NORMAN CHURCH, §g % aawi ^ai^at. THE ACTS OF THK APOSTLES. VoL I. Crown BvOf cloth, price ys. 6cl. A volume of the Third Series of the Expositor's Bible. IRELAND AND THE CELTIC CHURCH. A History of Ireland from St. Patrick to the English Conquest in 1172. Second Edition, Crown Zvo, chth, price gs. "Any one who can make the dry bones of ancient Irish history live again may feel sure of finding- an audience sympathetic, intelligent, and ever-growing. Dr. Stokes has this faculty in a high degree. This book will be a boon to that large and growing number of persons who desire to have a trustworthy account of the beginning of Irish history, and cannot study it for themselves in the great but often dull works of the original investigators. It collects the scattered and often apparently insignificant results of original workers in this field, interprets them for us, and brings them into relation with the broader and better-known facts of European history."— Westminster Review. " London : Hodder & Stoughton, 27, Paternoster Row, IRELAND AND THE ANGLO-NORMAN CHURCH. S iM0rg 0f ^xilmii rair ^mlg Cj^mfewrtg from tlgi ^nQla- REV. G. T. STOKES, D.D., Professor of Ecclesiastical History in the University of Dublin j Keeper of St/ Sepulchre's Public Library, commonly called Archbishop Marsh's Library ; and Vicar of All Saints', Blackrock. SECOND EDITION. HODDER AND STOUGHTON, 27, PATERNOSTER ROW, MDCCCXCII. -

Catholic Boarding Schools on the Western Frontier

FATHER SHANNON is the newly named president of the College of St. Thomas in St. Paul. The present article is based on his doctoral dissertation, which he has revised for publication by the Yale University Press. Under the title "Catholic Colonization on the Western Frontier," it is scheduled to appear in the spring of 1967. Catholic Boarding Schools on the WESTERN FRONTIER JAMES P. SHANNON TWELVE YEARS after Minnesota entered across the Great Plains to the boom towns the Union and five years after the Civil of the Black Hflls and toward the ports of War, the Red River trails were still the the Pacific. One great hindrance to such only major traces through western Minne expansion, however, was the scarcity of sota. At this late date, in 1870, a huge settlers in the Great Plains region. Gold in triangle of fertile farm land, bounded the Black Hills, wheat in the prairie states, roughly by imaginary lines connecting the and cattle from western grasslands might present cities of St. Paul in Minnesota, provide occasional pay loads for the rafl Fargo in North Dakota, and Sioux City in roads; but rail lines through unsettled re Iowa, remained for the most part unsettled gions could not pay their way. Nor could and uncultivated. they wait for the normal process of settle Then the trans-Mississippi railroads, de ment by gradual infiltration to reach the layed by the war, began building their lines West. Hence the more enterprising lines, especially those financed by federal land grants, undertook to subsidize the settle ^ Harold F. -

NOVEMBER 10, 2019 Very Rev

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Charlotte The Most Reverend Peter J. Jugis Bishop of Charlotte NOVEMBER 10, 2019 Very Rev. Christopher A. Roux 32ND SUNDAY OF ORDINARY TIME Rector & Pastor SUNDAY CYCLE: C — WEEKDAY CYCLE: I — PSALTER: WEEK IV WEEKEND MASSES Saturday Vigil: 5:30 pm Sunday: 7:30 am, 9 am, 11 am, and 12:30 pm WEEKDAY MASSES Monday - Friday: 12:10 pm Friday (school year): 8:30 am Saturday: 8 am HOLY DAY SCHEDULE 7:30 am, 12:10 pm, 7 pm CONFESSION Thirty minutes before daily Masses Saturday: 4 - 5 pm Sunday: 10 - 11 am ADORATION Wednesday: 8 am - 6 pm Sunday: 10 - 11 am PARISH OFFICE HOURS Monday - Friday: 9 am - 5 pm Closed Fridays during the summer Mission Statement We the members of The Cathedral of St. Patrick, through the mercy of God the Father, the grace of Jesus Christ, and the power of the Holy Spirit, seek to grow continually in knowledge of and love for God. We strive to enable ongoing conversion to Christ of our adults, to inspire faith in our children, and to be witnesses of His love in the greater community. Address: 1621 Dilworth Road East, Charlotte, NC 28203 Phone: (704) 334-2283 Fax: (704) 377-6403 Email: [email protected] Website: www.stpatricks.org DATE MASSES EVENTS 7:30 AM—Confession 8:00 AM † Sgt. Scott A. Koppenhafer 9:00—11:00 AM—Ablaze High School Program Saturday Requested by Sarah Myers 9:00 AM—YAM—Serving Lunch @ 1217 N. Tryon St. November 9th 5:30 PM † Arnaldo Crespo 2:00 PM—Wedding—Baker/Osborne Requested by the McNulty Family 4:00 PM—Confession 4:00 PM—Children’s Choir Practice 7:30 AM Pro Populo Sunday 9:00 AM † Scott Andrews November 10th Requested by the Carter Family 10:00—11:00 AM—Confession and Adoration 11:00 AM Joseph McGoldrick 10:15—11:30 AM—Adult Group Study 32nd Sunday of Requested by David McGoldrick Ordinary Time 12:30 PM Ramona McGoldrick Requested by David McGoldrick Monday 11:30 AM—Confession 12:10 PM Medeleine Villadolid November 11th 5:30 PM—Pietra Fitness Class Tuesday 12:10 PM Mary K. -

The Catholic University of America A

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA A Manual of Prayers for the Use of the Catholic Laity: A Neglected Catechetical Text of the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By John H. Osman Washington, D.C. 2015 A Manual of Prayers for the Use of the Catholic Laity: A Neglected Catechetical Text of the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore John H. Osman, Ph.D. Director: Joseph M. White, Ph.D. At the 1884 Third Plenary Council of Baltimore, the US Catholic bishops commissioned a national prayer book titled the Manual of Prayers for the Use of the Catholic Laity and the widely-known Baltimore Catechism. This study examines the Manual’s genesis, contents, and publication history to understand its contribution to the Church’s teaching efforts. To account for the Manual’s contents, the study describes prayer book genres developed in the British Isles that shaped similar publications for use by American Catholics. The study considers the critiques of bishops and others concerning US-published prayer books, and episcopal decrees to address their weak theological content. To improve understanding of the Church’s liturgy, the bishops commissioned a prayer book for the laity containing selections from Roman liturgical books. The study quantifies the text’s sources from liturgical and devotional books. The book’s compiler, Rev. Clarence Woodman, C.S.P., adopted the English manual prayer book genre while most of the book’s content derived from the Roman Missal, Breviary, and Ritual, albeit augmented with highly regarded English and US prayers and instructions. -

Thesis Approved Major Adviser Dean

Thesis Approved Major Adviser Dean THE HISTORY OF THE DIOCESE OF OMAHA (1910-1928) BY SISTER M. MAURICE ARMBRUSTER A THESIS Submitted to the Faculty of the Creighton University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Philosophy in the Department of History OMAHA, 1937 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page FOREWORD ........................................ IV INTRODUCTION .................................... VI I. THE ADMINISTRATION OF RIGHT REVEREND RICHARD SCANNELL, D. D., 1910-1916 1. Building of the New Cathedral................ 1 2. Reorganization of Parishes................... 3 3. Division of the Diocese in 1912.............. 7 4. Construction of New Churches and Schools..... 9 5. Erection of New Institutions and Enlargement of Old ...................................... 15 6. Work of Charitable Societies................. 19 7. Death of Bishop Scannell..................... 21 8. Growth in Catholicity........................ 23 9. Second Division of the Diocese............... 25 II. THE ADMINISTRATION OF MOST REVEREND JEREMIAH J. HARTY, D. D., 1916-1926 1. Appointment and Installation of the Archbishop 27 2. His Efforts to Secure Funds for the New Cathe dral and to Complete Its Construction......... 33 3. Reorganization of Parishes................... 35 4. Construction and Dedication of New Churches Schools...................................... 45 5. Introduction of New Institutions and Growth of Old................................... 52 6. Catholic Social Work in the Diocese.......... 59 7. Investiture of Two Monsignors................ 61 8. The Archbishop’s Departure for the West....... 62 III. THE ADMINISTRATION OF MOST REVEREND FRANCIS J. BECKMAN, D. D., 1926-1928 1. His Appointment as Administrator of the Diocese....................... 64 2. Investiture of Three Dignataries............. 66 3. Dedication of New Buildings.................. 68 4. Changes Effected in Missions and Parishes..... 69 5. Death of the Archbishop..................... -

Public Art in Parks Draft 28 03 14.Indd

Art in Parks A Guide to Sculpture in Dublin City Council Parks 2014 DUBLIN CITY COUNCIL We wish to thank all those who contributed material for this guide Prepared by the Arts Office and Parks and Landscape Services of the Culture, Recreation and Amenity Department Special thanks to: Emma Fallon Hayley Farrell Roisin Byrne William Burke For enquiries in relation to this guide please contact the Arts Office or Parks and Landscape Services Phone: (01) 222 2222 Email: [email protected] [email protected] VERSION 1 2014 1 Contents Map of Parks and Public Art 3 Introduction 5 1. Merrion Square Park 6 2. Pearse Square Park 14 3. St. Patrick’s Park 15 4. Peace Park 17 5. St. Catherine’s Park 18 6. Croppies Memorial Park 19 7. Wolfe Tone Park 20 8. St. Michan’s Park 21 9. Blessington Street Basin 22 10. Blessington Street Park 23 11. The Mater Plot 24 12. Sean Moore Park 25 13. Sandymount Promenade 26 14. Sandymount Green 27 15. Herbert Park 28 16. Ranelagh Gardens 29 17. Fairview Park 30 18. Clontarf Promenade 31 19. St. Anne’s Park 32 20. Father Collin’s Park 33 21. Stardust Memorial Park 34 22. Balcurris Park 35 2 20 Map of Parks and Public Art 20 22 21 22 21 19 19 17 18 10 17 10 18 11 11 9 9 8 6 7 8 6 7 2 2 5 4 5 4 1 3 12 1 3 12 14 14 15 13 16 13 16 15 3 20 Map of Parks and Public Art 20 22 21 22 21 19 19 1 Merrion Square Park 2 Pearse Square Park 17 18 St. -

Notre Dame Scholastic, Vol. 22, No. 01

xV rCH :t; PTRETIAHESEHDIIAJTIE ^iSCE'QMSI.SEHPEfi.YlCTimirS YIYE- QU55I • CB3S • HORITURUs VOL. XXII. NOTRE DAME, INDIANA, AUGUST 25, 1888. No. i. CariJien. LTp through the ether, blue, serene. ^^'Q'X'^^ Crowned by God's angels, borne by His might Into His Heart; O Virgin Queen, Thou dost ascend to the Lord of Light. Brush of the painter Raphael, Soul of ]Murillo, pious, high. Heart of Angelico,—each did well Three Song's. A part of Love's work in days gone by! Up throug'h the ether, blue, serene. IN HONOR OF THE VICRY REV. ED\V.\RD SORl.V, C. S. C. Towers Vour dome in the New World's light; August ij, iSSS. To the Old World's tributes its golden sheen Adds n&w splendor, through Love's great might. r.Y JCAURICK l--R.4.XCrS KGAX. Brusli of the painter Raphael, Soul of Murillo,grave and high; Love from all lands has brought you golden gifts, Artists of old, your best thoughts dwell Hope from all lands wafts golden prayers on high. Around this dome in the azure skvl Faith in all lands the golden chalice lifts,— For you, O Blessed, Earth entreats the sky. O Father, I will add a little song— Rome blesses you—the Pope, in his yeai", sends .A. little song of longing and of youth : His love most gracious on Our Lady's Day; Not writ to-day. but not writ very long. A train of pilgrims to your cloister wends. Of that dear land you love in very truth. -

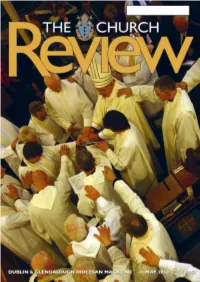

May 2004 Front

St. Brigid’s Church May Fair Stillorgan at Saturday, 29th May Church Grounds 10.00am. to 2.30p.m. St. Brigid’s, Church Road Rain – No Problem Most stalls under cover! A great family day out! *Plants *Cakes and Deli *Bottle Stall *Clothes *Books *Hats and Accessories *CD’s *Bric-a-Brac *Toys *Aladdin’s Cave *Sweets *Teas *Hamburgers *Smoothies *Bouncy Castle *Music *Games and much much more! 2 CHURCH REVIEW ChurCh of Ireland unIted dIoCeses of dublIn CHURCH REVIEW and GlendalouGh ISSN 0790-0384 The Most Reverend John R W Neill, M.A., L.L.D. Archbishop of Dublin and Bishop of Glendalough, Church Review is published monthly and Primate of Ireland and Metropolitan. usually available by the first Sunday. Please order your copy from your Parish by annual sub scription. €40 for 2010 AD. POSTAL SUBSCRIIPTIIONS//CIIRCULATIION Archbishop’s Lette r Copies by post are available from: Charlotte O’Brien, ‘Mountview’, The Paddock, Enniskerry, Co. Wicklow. E: [email protected] T: 086 026 5522. MAY 2010 The cost is the subscription and appropriate postage. the month of may this year is going to be one of some COPY DEADLIINE change. We will be welcoming the General synod of the Church All editorial material MUST be with the of Ireland back to its former home within the precincts of Christ Editor by 15th of the preceeding month, Church Cathedral. the dean of Christ Church is to be no matter what day of the week. Material commended for the vast amount of effort that he and all should be sent by Email or Word attachment.