Buayanyup River Action Plan BUAYANYUP RIVER Action Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Restoration After Removal of Pines at Gnangara Final

RESTORATION OF BANKSIA WOODLAND AFTER THE REMOVAL OF PINES AT GNANGARA: SEED SPECIES REQUIREMENTS AND PRESCRIPTIONS FOR RESTORATION A report prepared on behalf of the Department of Environment and Conservation for the Gnangara Sustainability Strategy Kellie Maher University of Western Australia May 2009 Restoration of Banksia woodland after the removal of pines at Gnangara: seed species requirements and prescriptions for restoration Report for the Department of Environment and Conservation Kellie Maher University of Western Australia Gnangara Sustainability Strategy Taskforce Department of Water 168 St Georges Terrace Perth Western Australia 6000 Telephone +61 8 6364 7600 Facsimile +61 8 6364 7601 www.gnangara.water.wa.gov.au © Government of Western Australia 2009 May 2009 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 , all other rights are reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Department of Conservation and Environment. This document has been commissioned/produced as part of the Gnangara Sustainability Strategy (GSS). The GSS is a State Government initiative which aims to provide a framework for a whole of government approach to address land use and water planning issues associated with the Gnangara groundwater system. For more information go to www.gnangara.water.wa.gov.au 1 Restoration of Banksia woodland after the removal of pines at Gnangara: seed species requirements and prescriptions for restoration A report to the Department of Environment and Conservation Kellie Maher University of Western Australia May 2009 2 Table of Contents List of Tables .................................................................................................................... -

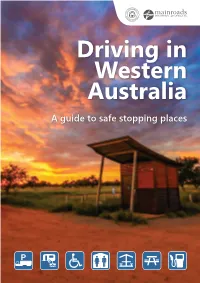

Driving in Wa • a Guide to Rest Areas

DRIVING IN WA • A GUIDE TO REST AREAS Driving in Western Australia A guide to safe stopping places DRIVING IN WA • A GUIDE TO REST AREAS Contents Acknowledgement of Country 1 Securing your load 12 About Us 2 Give Animals a Brake 13 Travelling with pets? 13 Travel Map 2 Driving on remote and unsealed roads 14 Roadside Stopping Places 2 Unsealed Roads 14 Parking bays and rest areas 3 Litter 15 Sharing rest areas 4 Blackwater disposal 5 Useful contacts 16 Changing Places 5 Our Regions 17 Planning a Road Trip? 6 Perth Metropolitan Area 18 Basic road rules 6 Kimberley 20 Multi-lingual Signs 6 Safe overtaking 6 Pilbara 22 Oversize and Overmass Vehicles 7 Mid-West Gascoyne 24 Cyclones, fires and floods - know your risk 8 Wheatbelt 26 Fatigue 10 Goldfields Esperance 28 Manage Fatigue 10 Acknowledgement of Country The Government of Western Australia Rest Areas, Roadhouses and South West 30 Driver Reviver 11 acknowledges the traditional custodians throughout Western Australia Great Southern 32 What to do if you breakdown 11 and their continuing connection to the land, waters and community. Route Maps 34 Towing and securing your load 12 We pay our respects to all members of the Aboriginal communities and Planning to tow a caravan, camper trailer their cultures; and to Elders both past and present. or similar? 12 Disclaimer: The maps contained within this booklet provide approximate times and distances for journeys however, their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Main Roads reserves the right to update this information at any time without notice. To the extent permitted by law, Main Roads, its employees, agents and contributors are not liable to any person or entity for any loss or damage arising from the use of this information, or in connection with, the accuracy, reliability, currency or completeness of this material. -

Coastal Land and Groundwater for Horticulture from Gingin to Augusta

Research Library Resource management technical reports Natural resources research 1-1-1999 Coastal land and groundwater for horticulture from Gingin to Augusta Dennis Van Gool Werner Runge Follow this and additional works at: https://researchlibrary.agric.wa.gov.au/rmtr Part of the Agriculture Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, Soil Science Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Recommended Citation Van Gool, D, and Runge, W. (1999), Coastal land and groundwater for horticulture from Gingin to Augusta. Department of Agriculture and Food, Western Australia, Perth. Report 188. This report is brought to you for free and open access by the Natural resources research at Research Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Resource management technical reports by an authorized administrator of Research Library. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. ISSN 0729-3135 May 1999 Coastal Land and Groundwater for Horticulture from Gingin to Augusta Dennis van Gool and Werner Runge Resource Management Technical Report No. 188 LAND AND GROUNDWATER FOR HORTICULTURE Information for Readers and Contributors Scientists who wish to publish the results of their investigations have access to a large number of journals. However, for a variety of reasons the editors of most of these journals are unwilling to accept articles that are lengthy or contain information that is preliminary in nature. Nevertheless, much material of this type is of interest and value to other scientists, administrators or planners and should be published. The Resource Management Technical Report series is an avenue for the dissemination of preliminary or lengthy material relevant the management of natural resources. -

Perth and Peel Green Growth Plan for 3.5 Million

v Government of Western Australia Department of the Premier and Cabinet Perth and Peel Green Growth Plan for 3.5 million Strategic Assessment of the Perth and Peel Regions Draft EPBC Act Strategic Impact Assessment Report Appendix C: Threatened Ecological Community Profiles December 2015 Acknowledgements This document has been prepared by Eco Logical Australia Pty Ltd and © Government of Western Australia Open Lines Consulting. Department of the Premier and Cabinet Disclaimer Dumas House This document may only be used for the purpose for which it was 2 Havelock Street commissioned and in accordance with the contract between Eco Logical Australia Pty Ltd and the Department of the Premier and West Perth WA 6005 Cabinet. The scope of services was defined in consultation with the Department of the Premier and Cabinet, by time and budgetary Website: www.dpc.wa.gov.au/greengrowthplan constraints imposed by the client, and the availability of reports Email: [email protected] and other data on the subject area. Changes to available information, legislation and schedules are made on an ongoing Tel: 08 6552 5151 basis and readers should obtain up to date information. Fax: 08 6552 5001 Eco Logical Australia Pty Ltd accepts no liability or responsibility Published December 2015 whatsoever for or in respect of any use of or reliance upon this report and its supporting material by any third party. Information provided is not intended to be a substitute for site specific assessment or legal advice in relation to any matter. Unauthorised use of this report in any form is prohibited. Strategic Assessment for the Perth and Peel Regions 1. -

Level 2 Fauna Survey MEELUP REGIONAL PARK

Level 2 Fauna Survey MEELUP REGIONAL PARK APRIL 2015 suite 1, 216 carp st (po box 470) bega nsw 2550 australia t (02) 6492 8333 www.nghenvironmental.com.au e [email protected] unit 18, level 3, 21 mary st suite 1, 39 fitzmaurice st (po box 5464) surry hills nsw 2010 australia wagga wagga nsw 2650 australia t (02) 8202 8333 t (02) 6971 9696 unit 17, 27 yallourn st (po box 62) room 15, 341 havannah st (po box 434) fyshwick act 2609 australia bathurst nsw 2795 australia t (02) 6280 5053 0488 820 748 Document Verification Project Title: MEELUP REGIONAL PARK Project Number: 5354 Project File Name: Meelup Regional Park Level 2 Fauna Survey v20150115 Revision Date Prepared by (name) Reviewed by (name) Approved by (name) DRAFT 27/03/15 Shane Priddle Nick Graham-Higgs Nick Graham-Higgs (SW Environmental) and Greg Harewood Final 17/04/15 Shane Priddle Shane Priddle Shane Priddle (SW Environmental) (SW Environmental) (SW Environmental) nghenvironmental prints all documents on environmentally sustainable paper including paper made from bagasse (a by- product of sugar production) or recycled paper. nghenvironmental is a registered trading name of NGH Environmental Pty Ltd; ACN: 124 444 622. ABN: 31 124 444 622 suite 1, 216 carp st (po box 470) bega nsw 2550 australia t (02) 6492 8333 www.nghenvironmental.com.au e [email protected] unit 18, level 3, 21 mary st suite 1, 39 fitzmaurice st (po box 5464) surry hills nsw 2010 australia wagga wagga nsw 2650 australia t (02) 8202 8333 t (02) 6971 9696 unit 17, 27 yallourn st (po box 62) room 15, 341 havannah st (po box 434) fyshwick act 2609 australia bathurst nsw 2795 australia t (02) 6280 5053 0488 820 748 Level 2 Fauna Survey MEELUP REGIONAL PARK CONTENTS LEVEL 2 FAUNA SURVEY ..................................................................................................................... -

Australia's National Programme of Action for the Protection of The

case study 21: the geographe bay region 2 Australia’s National Programme of Action for the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-Based Activities case study 21: the geographe bay region executive summary The Geographe Bay region, like many other Western Australian coastal areas, is facing the stress of excess nutrient loading to the coastal waterways and the adjacent marine ecosystem. Also like several other regions, the symptoms of this are the highly damaging toxic algal blooms that occur frequently in the fresh and estuarine waters of the region, and the major impacts for agriculture, tourism, public health and biodiversity. These issues were first recognised in the Geographe Bay region in the 1990s, and a community-led process was initiated to develop and implement an integrated catchment management plan designed to reduce nutrient inputs and restore environmental values to their former levels. The catchment management plan is now implemented by Geographe Catchment Council (GeoCatch), a small community-based organisation established for this purpose. The catchment management plan is a voluntary instrument designed to re-orient rural and urban management practices towards more desirable objectives through education and awareness raising, through demonstrated examples of best practice, and through promotion of specific measures for adoption by local and state government agencies. A large number of important strategies have been developed and implemented, and new strategies are being developed. However, although the catchment management plan provides for monitoring and evaluation to be conducted, there appear to be very few examples that demonstrate the success of the plan in facilitating improved catchment health (such as by reducing nutrient loading to rivers or the bay). -

11.3 Infrastructure Services Attachments

SHIRE OF AUGUSTA MARGARET RIVER ORDINARY COUNCIL MEETING 10 OCTOBER 2018 11.3 Infrastructure Services Attachments ITEM NO SUBJECT PAGE 11.3.1 LEEUWIN NATURALISTE 2050 CYCLING STRATEGY – FOR ADOPTION 1 11.3.3 CLOSURE OF OLD BURNSIDE ROAD ALIGNMENT, BURNSIDE 102 SHIRE OF AUGUSTA MARGARET RIVER ORDINARY COUNCIL MEETING 10 OCTOBER 2018 11.3 Infrastructure Services 11.3.1 LEEUWIN NATURALISTE 2050 CYCLING STRATEGY – FOR ADOPTION Attachment 1 – Leeuwin Naturaliste 2050 Cycling Strategy (final) Attachment 2 – Implementation Program 1 Department of Transport LEEUWIN- NATURALISTE 2050 CYCLING STRATEGY A LONG-TERM VISION TO REALISE THE SUBREGION’S CYCLING POTENTIAL 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Cities and towns with high levels of cycling enjoy a range of economic, environmental and social benefits. Not only is cycling proven to reduce traffic congestion and improve air quality, it also helps to create more vibrant and welcoming communities. Cycling can facilitate new forms of industry (such as cycle-tourism) and more generally, it enables people to live happier, healthier and more active lives. Fundamentally, increasing cycling mode share is about improving quality of life – something that is critical for attracting and retaining people in regional areas. The key to increasing cycling mode share is The Leeuwin-Naturaliste 2050 Cycling Strategy will providing infrastructure which is not only safe help inform future investment through the Regional and convenient, but also competitive against Bicycle Network Grants Program and potentially other modes of transport. To achieve this, cycling other funding sources. needs to be prioritised ahead of other modes in In developing this strategy, extensive consultation appropriate locations and integrated with adjoining has been undertaken with key stakeholders and land use. -

Ministerial Decisions at at 12 October 2018

MINISTERIAL DECISIONS AS AT OCTOBER 2020 Recently received Awaiting decision pursuant to section 45(7) of Pending submission to Pending decision by Ministerial decision the Environmental Protection Act 1986 Minister for Aboriginal Affairs Minister for Aboriginal Affairs APPLICANT / MINISTERIAL LAND PURPOSE LANDOWNER DECISION September 2020 Lot 140 on DP 39512, CT 2227/905, 140 South Western Highway, Land Act No. 11238201, Lot 141 on DP 39512, CT 2227/906, 141 South Western Highway, Land Act No. 11238202, 202 Vittoria Road, Land Act No. 11891696, Glen Iris. Pending Intersection Vittoria Road Lot 201 on DP 57769, CT 2686/979, 201 submission to Main Roads South Western Highway South Western Highway, Land Act No. Minister for Western Australia upgrade and Bridge 0430 11733330, Lot 202 on DP 56668, CT Aboriginal Affairs replacement, Picton. 2754/978, Picton. Road Reserve, Land Act No.s 1575861, 11397280, 11397277, 1347375, and 1292274. Unallocated Crown Land, South Western Highway, Land Act No.s 11580413, 1319074 and 1292275, Picton. Pending Fortifying Mining Pty Ltd – Tenements M25/369, P25/2618, submission to Fortify Mining Pty Majestic North Project. To P25/2619, P25/2620, and P25/2621, Minister for Ltd undertake exploration and Goldfields. Aboriginal Affairs resource delineation drilling Reserve 34565, Lot 11835 on Plan Pending 240379, CT 3141/191, Coode Street, Landscape enhancement submission to City of South South Perth, Land Act No. 1081341 and and river restoration. To Minister for Perth Reserve 48325, Lot 301 on Plan 47451, construct the Waterbird Aboriginal Affairs CT 3151/548, 171 Riverside Drive, Land Refuge Act No. 11714773, Perth Pending Able Planning and Lot 501 on Plan 23800, CT 2219/673, submission to Lot 501 Yalyalup Urban Project 113 Vasse Highway, Yalyalup, Land Act Minister for Subdivision. -

In This Issue in This Issue

No. 14 Hakea IN THIS ISSUE DHakea The first collection of This issue of Seed Notes Hakea was made in 1770 will cover the genus by Joseph Banks and Daniel Hakea. Solander from the Endeavour D Description expedition. The genus was described in 1797 by Schrader D Geographic and Wendland, and named distribution and habitat after Baron von Hake, a 19th century patron of botany, D Reproductive biology in Hanover. Plants were D Seed collection introduced into cultivation in England before that time. D Seed quality D assessment Hakea neurophylla. Photo – Sue Patrick D Seed germination D Recommended reading Description DMost hakeas are shrubs, woody and persistent; whereas ranging from small to low Grevillea has non-woody and medium height. They can non-persistent fruits. Most be useful for screening or as Hakea species have tough, groundcovers. Without fruits, pungent foliage that may be Hakea and Grevillea can be terete (needle-like), flat or confused. Both have flowers divided into segments. The with four tepals (petals and leaves are generally a similar sepals combined), an erect colour on both sides. Plants or recurved limb in bud and are usually single or multi- a similar range of leaf and stemmed shrubs, with smooth pollen presenter shapes. But bark, although there are the fruits are very different. ‘corkwood‘ hakeas with thick, Hakea fruits are generally deeply furrowed bark. Many Hakea can resprout after fire or disturbance, and these tend to be the species exhibiting multiple stems. The flowers are generally bisexual and range in colour from cream to green to pink, red, orange and mauve. -

Ludlow Titanium Minerals Mine, 34 Kilometres South of Bunbury

Ludlow Titanium Minerals Mine, 34 Kilometres South of Bunbury Cable Sands (WA) Pty Ltd Report and recommendations of the Environmental Protection Authority Environmental Protection Authority Perth, Western Australia Bulletin 1098 May 2003 ISBN. 0 7307 6734 5 ISSN. 1030 - 0120 Assessment No. 1385 Summary and recommendations Cable Sands (WA) Pty Ltd proposes to develop a mineral sands mine in a section of State Forest No.2, near Ludlow. This report provides the Environmental Protection Authority’s (EPA’s) advice and recommendations to the Minister for the Environment and Heritage on the environmental factors relevant to the proposal. Section 44 of the Environmental Protection Act 1986 requires the EPA to report to the Minister for the Environment and Heritage on the environmental factors relevant to the proposal and on the conditions and procedures to which the proposal should be subject, if implemented. In addition, the EPA may make recommendations as it sees fit. Relevant environmental factors The EPA decided that the following environmental factors relevant to the proposal required detailed evaluation in this report: (a) Tuart conservation; (b) Rehabilitation; and (c) Fauna. There were a number of other factors which were relevant to the proposal, but the EPA is of the view that the information set out in Appendix 3 provides sufficient evaluation. Conclusion The EPA has considered the proposal by Cable Sands (WA) Pty Ltd to develop a mineral sands mine in a section of State Forest No.2, 34 km south of Bunbury. Cable Sands (WA) Pty Ltd has worked hard with the community and government to develop an environmentally acceptable proposal in a region which has high significance for conservation. -

ABSTRACT One Htmdy'ed and Ni.Nefu -Fout Lichen Species Are Reported from Westerm Australia Ui,Th Infornation on Their Dlstr

WESTERNAUSTRALIAN HERBARIUM RESEARCH NOTES No. 7, 1982: 17-29 SYSTEMATICLIST WITH DISTRIBUTIONSOF THE LICHEN SPECIES OF WESTERNAUSTRALIA, BASEDON COLLECTIONSIN THE WESTERNAUSTRALIAN HERBARIUM By R.M. Richardson and D.H.S. Richardson Westem Austnalian Herbariun, GeoxgeSt., South Perth, l{ .A. 6151 (Present address: School of Botany, Trinity College, Dublin 2, Ireland). ABSTRACT One htmdy'edand ni.nefu -fout Lichen species are reported from WestermAustralia ui,th infornation on their dLstr"tbution. The Li,st of species is based on prouisionalLy deternrined speci.mens deposited in the Westerm Austt'alitt Herbar"iwn. ?he Lichen flora of the state i,s il:Luerse, the most Lzrcur"ient grotsth occurrLng i,n the south-uesltem comey. As LittLe i-s kraan of the Lichern of the z:emaird.er of the state " parti.cular:Ly the north-east, tnrch research remaina to be done on thei.r. taronom7 and distr"ibut ion. INTRODUCTION Little intensive research has been done on the lichen flora of Western Australia though collections were nade at quite an early date, The earliest taxononic publication appears to be that of Fries (1846), who described 25 species, the Tesult of collections by L. Preiss fron Rottnest Island and the south-west part of the state. The following year Taylor (1847) listed 1"6 lichens from Western Australia in his catalogue of the W.J. Hooker Herbariun. Mueller (1887) collated the early records and produced a list of Australian lichens, includlng two species from Western Australia which had not previously been recorded:. Cladia aggregata and CLadon'Laretipot u", the latter now segregated in Western Australia as Cla&ia ferdi,nandii. -

Shrubland Association on Southern Swan Coastal Plain Ironstone (Busselton Area) (Southern Ironstone Association)

INTERIM RECOVERY PLAN NO. 215 SHRUBLAND ASSOCIATION ON SOUTHERN SWAN COASTAL PLAIN IRONSTONE (BUSSELTON AREA) (SOUTHERN IRONSTONE ASSOCIATION) INTERIM RECOVERY PLAN 2005-2010 by Rachel Meissner and Val English Photo: Rachel Meissner March 2005 Department of Conservation and Land Management Species and Communities Branch PO Box 51, Wanneroo, WA 6946. FOREWORD Interim Recovery Plans (IRPs) are developed within the framework laid down in Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM) Policy Statements Nos 44 and 50. IRPs outline the recovery actions that are required to urgently address those threatening processes most affecting the ongoing survival of threatened taxa or ecological communities, and begin the recovery process. CALM is committed to ensuring that Critically Endangered ecological communities are conserved through the preparation and implementation of Recovery Plans or Interim Recovery Plans and by ensuring that conservation action commences as soon as possible and always within one year of endorsement of that rank by CALM's Director of Nature Conservation. This Interim Recovery Plan replaces plan number 44 – „Shrublands on southern Swan Coastal Plain Ironstones‟, Interim Recovery Plan 1999-2002, by V. English. This Interim Recovery Plan will operate from March 2005 to February 2010 but will remain in force until withdrawn or replaced. It is intended that, if the ecological community is still ranked Critically Endangered, this IRP will be reviewed after five years and the need for a full Recovery Plan will be assessed. This IRP was given Regional approval on 21 November 2005 and was approved by the Director of Nature Conservation 13 December 2005. The allocation of staff time and provision of funds identified in this Interim Recovery Plan is dependent on budgetary and other constraints affecting CALM, as well as the need to address other priorities.