Shadow Theaters of the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: the Life Cycle of the Child Performer

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: The life cycle of the child performer by Lyndsay Barnbrook A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Humanities Faculty School of Music April 2016 \A person's a person, no matter how small." Dr. Seuss UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON Abstract Humanities Faculty School of Music Doctor of Philosophy The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: The life cycle of the child performer by Lyndsay Barnbrook The purpose of the research reported here is to explore the part played by children in musical theatre. It aims to do this on two levels. It presents, for the first time, an historical analysis of involvement of children in theatre from its earliest beginnings to the current date. It is clear from this analysis that the role children played in the evolution of theatre has been both substantial and influential, with evidence of a number of recurring themes. Children have invariably made strong contributions in terms of music, dance and spectacle, and have been especially prominent in musical comedy. Playwrights have exploited precocity for comedic purposes, innocence to deliver difficult political messages in a way that is deemed acceptable by theatre audiences, and youth, recognising the emotional leverage to be obtained by appealing to more primitive instincts, notably sentimentality and, more contentiously, prurience. Every age has had its child prodigies and it is they who tend to make the headlines. However the influence of educators and entrepreneurs, artistically and commercially, is often underestimated. Although figures such as Wescott, Henslowe and Harris have been recognised by historians, some of the more recent architects of musical theatre, like Noreen Bush, are largely unheard of outside the theatre community. -

Storytelling and Community: Beyond the Origins of the Ancient

STORYTELLING AND COMMUNITY: BEYOND THE ORIGINS OF THE ANCIENT THEATRE, GREEK AND ROMAN by Sarah Kellis Jennings Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors in the Department of Theatre Texas Christian University Fort Worth, Texas May 3, 2013 ii STORYTELLING AND COMMUNITY: BEYOND THE ORIGINS OF THE ANCIENT THEATRE, GREEK AND ROMAN Project Approved: T.J. Walsh, Ph.D. Department of Theatre (Supervising Professor) Harry Parker, Ph.D. Department of Theatre Kindra Santamaria, Ph.D. Department of Modern Language Studies iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................iv INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1 GREEK THEATRE .............................................................................................................1 The Dithyramb ................................................................................................................2 Grecian Tragedy .............................................................................................................4 The Greek Actor ............................................................................................................. 8 The Satyr Play ................................................................................................................9 The Greek Theatre Structure and Technical Flourishes ...............................................10 Grecian -

Mapping the History of Malaysian Theatre: an Interview with Ghulam-Sarwar Yousof

ASIATIC, VOLUME 4, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2010 Mapping the History of Malaysian Theatre: An Interview with Ghulam-Sarwar Yousof Madiha Ramlan & M.A. Quayum1 International Islamic University Malaysia It seems that a rich variety of traditional theatre forms existed and perhaps continues to exist in Malaysia. Could you provide some elucidation on this? If you are looking for any kind of history or tradition of theatre in Malaysia you won’t get it, because of its relative antiquity and the lack of records. Indirect sources such as hikayat literature fail to mention anything. Hikayat Raja-Raja Pasai mentions Javanese wayang kulit, and Hikayat Patani mentions various music and dance forms, most of which cannot be precisely identified, but there is no mention of theatre. The reason is clear enough. The hikayat generally focuses on events in royal court, while most traditional theatre developed as folk art, with what is known as popular theatre coming in at the end of the 19th century. There has never been any court tradition of theatre in the Malay sultanates. In approaching traditional theatre, my own way has been to first look at the proto- theatre or elementary forms before going on to the more advanced ones. This is a scheme I worked out for traditional Southeast Asian theatre. Could you elaborate on this? Almost all theatre activity in Southeast Asia fits into four categories as follows: Proto-Theatre, Puppet Theatre, Dance Theatre and Opera. In the case of the Philippines, one could identify a separate category for Christian theatre forms. Such forms don’t exist in the rest of the region. -

History of Theatre the Romans Continued Theatrical Thegreek AD (753 Roman Theatre fi Colosseum Inrome, Which Was Built Between Tradition

History of theatre Ancient Greek theatre Medieval theatre (1000BC–146BC) (900s–1500s) The Ancient Greeks created After the Romans left Britain, theatre purpose-built theatres all but died out. It was reintroduced called amphitheatres. during the 10th century in the form Amphitheatres were usually of religious dramas, plays with morals cut into a hillside, with Roman theatre and ‘mystery’ plays performed in tiered seating surrounding (753BC–AD476) churches, and later outdoors. At a the stage in a semi-circle. time when church services were Most plays were based The Romans continued the Greek theatrical tradition. Their theatres resembled Greek conducted in Latin, plays were on myths and legends, designed to teach Christian stories and often involved a amphitheatres but were built on their own foundations and often enclosed on all sides. The and messages to people who could ‘chorus’ who commented not read. on the action. Actors Colosseum in Rome, which was built between wore masks and used AD72 and AD80, is an example of a traditional grandiose gestures. The Roman theatre. Theatrical events were huge works of famous Greek spectacles and could involve acrobatics, dancing, playwrights, such as fi ghting or a person or animal being killed on Sophocles, Aristophanes stage. Roman actors wore specifi c costumes to and Euripedes, are still represent different types of familiar characters. performed today. WORDS © CHRISTINA BAKER; ILLUSTRATIONS © ROGER WARHAM 2008 PHOTOCOPIABLE 1 www.scholastic.co.uk/junioredplus DECEMBER 2008 Commedia dell’Arte Kabuki theatre (1500s Italy) (1600s –today Japan) Japanese kabuki theatre is famous This form of Italian theatre became for its elaborate costumes and popular in the 16th and 17th centuries. -

Evolution of Street Theatre As a Tool of Political Communication Sangita

Evolution of Street Theatre as a tool of Political Communication Sangita De & Priyam Basu Thakur Abstract In the post Russian Revolution age a distinct form of theatrical performance emerged as a Street Theatre. Street theatre with its political sharpness left a crucial effect among the working class people in many corner of the world with the different political circumstances. In India a paradigm shift from proscenium theatre to the theatre of the streets was initiated by the anti-fascist movement of communist party of India under the canopy of Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA). In North India Street theatre was flourished by Jana Natya Manch (JANAM) with the leadership of Safdar Hashmi. This paper will explore the background of street theatre in India and its role in political communication with special reference to historical and analytical study of the role of IPTA, JANAM etc. Keywords: Street Theatre, Brecht, Theatre of the Oppressed, Communist Party of India (CPI), IPTA, JANAM, Safdar Hashmi, Utpal Dutta. Introduction Scholars divided the history of theatre forms into the pre-Christian era and Christian era. Aristotle’s view about the structure of theatre was based on Greek tragedy. According to the scholar Alice Lovelace “He conceived of a theatre to carry the world view and moral values of those in power, investing their language and symbols with authority and acceptance. Leaving the masses (parties to the conflict) to take on the passive role of audience...........The people watch and through the emotions of pity & grief, suffer with him.” Bertolt Brecht expressed strong disagreement with the Aristotelian concept of catharsis. -

![Curriculum Vitae [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0393/curriculum-vitae-pdf-1260393.webp)

Curriculum Vitae [PDF]

1 CURRICULUM VITAE 1. John Emigh Professor Theatre, Speech, and Dance and English 2. 3591 Pawtucket Ave Riverside, RI 02915 3. Education: Ph. D. Tulane University (Theatre: Theory and Criticism) 1971 Dissertation: "Love and Honor,1636: A Comparative Study of Corneille's Le Cid and Calderón's Honor Plays" M.F.A. Tulane University (Theatre: Directing) 1967 Thesis: "Analysis, Adaptation, and Production Book of Georg Büchner's Woyzeck" B.A. Amherst College (English and Dramatic Arts) 1964 Thesis: Production of Samuel Beckett's "Waiting for Godot" Additional education and training: 1999-2000 – I Gusti Ngurah Windia (private study, Balinese masked dance]–7/99, 7/01 1983-84 - Intensive workshop in Feldenkrais technique - 1/84 1976-77 - Valley Studio Mime School (corporal mime) - 8/76 - Kristen Linklater and the Working Theatre (intensive workshop in voice and movement for the stage) - 6/77 1974-75 - I Nyoman Kakul (private study, Balinese masked dance -12/74-4/75 1971-72 - American Society for Eastern Arts (Balinese music and dance, Javanese shadow puppetry) - 6-8/72, also 8/76 1967-68 - Columbia University (voice) - 7-8/67 1966-67 - Circle in the Square Theatre School (acting) - 7-8/66 1961-62 - University of Malaga, Spain (curso para estranjeros)-12/61-2/62 4. Professional Appointments: Brown University: 1990- Professor of Theatre, Speech, and Dance and of English 1987- 92 Chairperson, Department of Theatre, Speech, and Dance 1974- 90 Associate Professor of English and Theatre Arts (1986: Theatre, Speech and Dance); Associate Director, University -

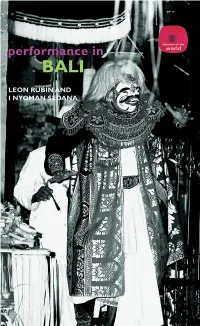

Performance in Bali

Performance in Bali Performance in Bali brings to the attention of students and practitioners in the twenty-first century a dynamic performance tradition that has fasci- nated observers for generations. Leon Rubin and I Nyoman Sedana, both international theatre professionals as well as scholars, collaborate to give an understanding of performance culture in Bali from inside and out. The book describes four specific forms of contemporary performance that are unique to Bali: • Wayang shadow-puppet theatre • Sanghyang ritual trance performance • Gambuh classical dance-drama • the virtuoso art of Topeng masked theatre. The book is a guide to current practice, with detailed analyses of recent theatrical performances looking at all aspects of performance, production and reception. There is a focus on the examination and description of the actual techniques used in the training of performers, and how some of these techniques can be applied to Western training in drama and dance. The book also explores the relationship between improvisation and rigid dramatic structure, and the changing relationships between contemporary approaches to performance and traditional heritage. These culturally unique and beautiful theatrical events are contextualised within religious, intel- lectual and social backgrounds to give unparalleled insight into the mind and world of the Balinese performer. Leon Rubin is Director of East 15 Acting School, University of Essex. I Nyoman Sedana is Professor at the Indonesian Arts Institute (ISI) in Bali, Indonesia. Theatres of the World Series editor: John Russell Brown Series advisors: Alison Hodge, Royal Holloway, University of London; Osita Okagbue, Goldsmiths College, University of London Theatres of the World is a series that will bring close and instructive contact with makers of performances from around the world. -

Drama 204.3 History of Drama and Theatre from 1850 to the Present

Drama 204.3 History of Drama and Theatre From 1850 to the Present History of Theatre, dominantly in the Western Tradition, from the rise of the modern theatre to the present day. Evolution of theatrical production (acting, directing, production, theatre architecture) will be emphasized, with assigned plays being examined largely within the context of the production and performance dynamics of their period. Instructor Moira Day Rm 187, John Mitchell 966-5193 (Off.) 653-4729 (Home) 1-780-466-8957 (emergency only) [email protected] http://www.ualberta.ca/~normang/Pika.html Office Hours MW 11:00 - 1:00 Booklist ***Klaus, Gilbert, Field, ed. Stages of Drama (5th edition). Boston: Bedford/St.Martin’s, 2003. Brockett, Oscar. History of the Theatre (9th edition). Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2003. *** Theatre History Notes Package. Bookstore Grades and Course Information ***Mid-Term 10% Quizzes 10% Response Papers (4 x5%) 20% Group work 20% Participation 10%*** Final Exam 30% ---- 100% I will be in class five minutes ahead of time for consultation, and begin and end lectures on time. I will also return quizzes within TWO class periods after giving them, and return exams within TEN DAYS after giving them. Exams, quizzes and papers not picked up at that class time can be picked up during office hours. Students are expected to be punctual and to submit all classwork on time. Any requests for an extension must be submitted *** ***one week in advance of the formal deadline. ***Unexcused late assignments***, except in the case of certifiable illness or death in the family, will be heavily penalized (10% per day deducted). -

History of Theatre Naomi Holcombe KS3 KS3

History of theatre Naomi Holcombe KS3 KS3 Introduction Naomi Holcombe is a drama teacher and Head of Year 8 at Queen Elizabeth’s The main aim of this scheme is for students to understand different periods in Hospital school in Bristol. She has been theatre history and to learn to perform in those styles. teaching the Edexcel course at GCSE for 10 years. As drama teachers we often cover a range of theatre styles and genres from different time periods at KS3, but it is helpful for students to be able to contextualise these styles in terms of theatre history. Learning about the origins of drama and how it has developed can help students to understand how modern drama has evolved and gives them an overview of theatre across the world, from many thousands of years ago to the present day. Organised into six one-hour lessons delivered over six weeks, this scheme can then be followed by a more in-depth study of particular periods or plays. It is suitable for Years 7, 8 or 9 and can be tailored to the ability level of your students. There are opportunities to stretch and challenge within the lessons or develop lessons further in order to take more time than is suggested here. In this scheme I have referenced and made use of some wonderful National Theatre videos that are on YouTube. These are very useful as they clearly explain and introduce students to key aspects of each style of theatre. Learning objectives Students will gain the following knowledge/skills during the 6 lessons: Resources to be sourced: f An awareness of the first forms of drama f Camera/iPad to record performances f Turning rituals into drama f Internet (YouTube clips) f Understanding the importance of Greek theatre within drama history f Original texts (extracts are provided f Consideration of how the Church used drama to convey morals and messages in the Resources at the end of this scheme, full length texts need to be f Have used example scenarios to create their own commedia dell’arte scenes sourced): Everyman; The Tempest; and characters Waiting for Godot. -

History of Theatre Review

Name: _____________________________________ Date: _______ Period: _______ History of Theatre Review 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Across 24. This French Neoclassical playwright who wrote 9. This Restoration playwright wrote "The Way of the 4. ___________ is credited with being the first actor "Tartuffe" was born Jean Baptiste Poquelin, but is better World." in Ancient Greek theatre. know as _______________. 10. This was a crane that the Ancient Greeks used to 7. This French Cardinal was responsible for 25. The god whose worship by the Ancient Greeks was lower an actor playing one of the Olympian gods from maintaining the purity of French language and literature the beginning of Western theatre. "heaven" to "earth." and "policing" French drama. Down 12. Means "seeing place" for the Ancient Greeks. 11. These were triangular prisms that allowed the 1. During the Italian Renaissance, this type of theatre 13. In Ancient Greek theatre, tragedy masks were Ancient Greeks to make 3 different background scenes. was the most prevalent; travelling companies of beautiful, but comedy masks were ___________. 15. Means "dancing place" for the ancient Greeks. professional actors toured the countryside, performing in 14. This famous Greek playwright wrote the tragedy 16. This is where the "groundlings" viewed the plays in towns and villages across Italy. "Oedipus Rex" (Oedipus the King). Elizabethan theatres. 2. ___________________ plays were based on 17. The Greek word for "goat," which would be sacrificed 18. This Elizabethan playwright wrote "The Tragical stories from the Bible in Medieval times. -

Theatre Arts (THEAT) 1

Theatre Arts (THEAT) 1 THEAT 033 Technical Theatre in Production 1-3 Units THEATRE ARTS (THEAT) Students gain practical experience in technical theatre production in one or more of the following activities: building and maintaining sets, THEAT 002 Beginning Acting 3 Units properties, and costumes; rigging, focusing and running lights; setting up Students will apply basic acting theory and techniques to in-class and using sound equipment; stage and house management. (C-ID THTR performances. They will develop skills of interpretation of drama using 192) script analysis and characterization. Special attention is paid to skills Lecture Hours: None Lab Hours: 3 Repeatable: Yes Grading: L for performance: memorization, stage movement, vocal production, and Advisory Level: Read: 3 Write: 3 Math: None improvisation. (C-ID THTR 151) Transfer Status: CSU/UC Degree Applicable: AA/AS Lecture Hours: 2 Lab Hours: 3 Repeatable: No Grading: L CSU GE: None IGETC: None District GE: None Advisory Level: Read: 4 Write: 4 Math: None Transfer Status: CSU/UC Degree Applicable: AA/AS THEAT 040 Introduction to Film 3 Units CSU GE: C1 IGETC: None District GE: C1 Students will be introduced to film and television media through viewing and analysis of cinema and video productions from a variety of THEAT 003 Intermediate Acting 3 Units cultures. The work of filmmakers is examined including screenwriting, Students apply intermediate acting techniques to character study and cinematography, editing, visual and sound design, acting, and directing. scene work. Students will expand their understanding of the acting Lecture Hours: 2.5 Lab Hours: 1.5 Repeatable: No Grading: L process through in-class performances, monologues, and scenes. -

Understanding Drama.Pdf

mathematics HEALTH ENGINEERING DESIGN MEDIA management GEOGRAPHY EDUCA E MUSIC C PHYSICS law O ART L agriculture O BIOTECHNOLOGY G Y LANGU CHEMISTRY TION history AGE M E C H A N I C S psychology Understanding Drama Subject: UNDERSTANDING DRAMA Credits: 4 SYLLABUS One-act Plays Introduction to One-Act Plays, The Bishop's Candlesticks, Refund, The Monkey's Paw Macbeth Background Study to the Play & Discussion, Characterisation & Techniques A Doll's House: A Study Guide Introduction to Drama, Themes and Characterisation, Critical Analysis: Acts and Dramatic Techniques, Arms and The Man: A study Guide Ghashiram Kotwal : A Study Guide Dramatic Techniques, Themes and Characterisation, Background and Plot, Ghashiram Kotwal Suggested Readings: 1. Indian Drama in English : Chakraborty Kaustav 2. The Cambridge Companion To George Bernard Shaw: Christopher Innes 3. Dramatic Techniques: George Pierce baker CONTENTS Chapter-1: Origin Of Drama Chapter-2: The Elements Of Drama Chapter-3: Asian Drama Chapter-4: Forms Of Drama Chapter-5: Dramatic Structure Chapter-6: Comedy (Drama) Chapter-7: Play (Theatre) Chapter-8: Theories Of Theatre Chapter-9: Theater Structure Chapter-10: Shakespeare's Plays Chapter-11: American Drama Chapter-12: Othello – William Shakespear Chapter-1 Origin of Drama Drama is the specific mode of fiction represented in performance. The term comes from a Greek word meaning "action" (Classical Greek: drama), which is derived from the verb meaning "to do" or "to act‖. The enactment of drama in theatre, performed by actors on a stage before an audience, presupposes collaborative modes of production and a collective form of reception. The structure of dramatic texts, unlike other forms of literature, is directly influenced by this collaborative production and collective reception.