Performance in the Cabinet of Curiosities Or, the Boy Who Lived in the Tree

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Luis Venegas What to Read, Watch, Listen To, and Know About to Become a Bullet-Proof Style Expert

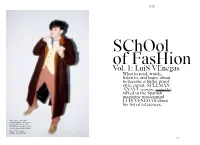

KUltur kriTik SChOol of FasHion Vol. 1: LuiS VEnegas What to read, watch, listen to, and know about to become a bullet-proof style expert. SULEMAN ANAYA (username: vertiz136) talked to the Spanish magazine mastermind LUIS VENEGAS about his list of references. coat, jacket, and pants: Lanvin Homme, waistcoat: Polo Ralph Lauren, shirt: Dior Homme, bow tie: Marc Jacobs, shoes: Pierre Hardy photo: Chus Antón, styling: Ana Murillas 195 KUltur SChOol kriTik of FasHion At 31, Luis Venegas is already a one-man editorial powerhouse. He produces and publishes three magazines that, though they have small print runs, have a near-religious following: the six-year-old Fanzine 137 – a compendium of everything Venegas cares about, Electric Youth (EY!) Magateen – an oversized cornucopia of adolescent boyflesh started in 2008, and the high- ly lauded Candy – the first truly queer fashion magazine on the planet, which was launched last year. His all-encompassing, erudite view of the fashion universe is the foundation for Venegas’ next big project: the fashion academy he plans to start in 2011. It will be a place where people, as he says, “who are interested in fashion learn about certain key moments from history, film and pop culture.” To get a preview of the curriculum at Professor Venegas’ School of Fashion, Suleman Anaya paid Venegas a visit at his apartment in the Madrid neighborhood of Malasaña, a wonderful space that overflows with the collected objects of his boundless curiosity. Television ● Dynasty ● Dallas What are you watching these days in your scarce spare time? I am in the middle of a Dynasty marathon. -

The Hat Magazine Archive Issues 1 - 10

The Hat Magazine Archive Issues 1 - 10 Issue No Date Main Articles Workroom Process ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 1 Apr-Jun 1999 Luton - Ascot Shoot - Sean Barratt Feathers - Dawn Bassam -Trade Shows - Fashion Museums & Dillon Wallwork ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 2 Jul-Sep 1999 Paris – Marie O’Regan – Royal Ascot Working with crinn with - Student Shows – Geoff Roberts Frederick Fox ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 3 Oct-Nov 1999 Hat Designer of the Year ’99 - Block Making with Men in Hats, shoot – Trade Fairs Serafina Grafton-Beaves ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 4 Jan-Mar 2000 Mitzi Lorenz – Philip Treacy couture Working with sinamay (1) show Paris – Florence – Bridal shoot with Marie O’Regan Street page – Trades Shows ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 5 Apr-Jun 2000 Coco Chanel – Trade Fairs Working with sinamay (2) Dagmara Childs – Knits Shoot with Marie O’Regan Street page - Trade Shows ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 6 Jul-Sep 2000 Luton shoot – Royal Ascot Working with -

ROSITA MISSONI MARCH 2015 MARCH 116 ISSUE SPRING FASHION SPRING $15 USD 7 2527401533 7 10 03 > > IDEAS in DESIGN Ideas in Design in Ideas

ISSUE 116 SPRING FASHION $15 USD 10> MARCH 2015 03> 7 2527401533 7 ROSITA MISSONI ROSITA IDEAS IN DESIGN Ideas in Design in Ideas STUDIO VISIT My parents are from Ghana in West Africa. Getting to the States was Virgil Abloh an achievement, so my dad wanted me to be an engineer. But I was much more into hip-hop and street culture. At the end of that engi- The multidisciplinary talent and Kanye West creative director speaks neering degree, I took an art-history class. I learned about the Italian with us about hip-hop, Modernism, Martha Stewart, and the Internet Renaissance and started thinking about creativity as a profession. I got from his Milan design studio. a master’s in architecture and was particularly influenced by Modernism and the International Style, but I applied my skill set to other projects. INTERVIEW BY SHIRINE SAAD I was more drawn to cultural projects and graphic design because I found that the architectural process took too long and involved too many PHOTOS BY DELFINO SISTO LEGNANI people. Rather than the design of buildings, I found myself interested in what happens inside of them—in culture. You’re wearing a Sterling Ruby for Raf Simons shirt. What happens when art and fashion come together? Then you started working with Kanye West as his creative director. There’s a synergy that happens when you cross-pollinate. When you use We’re both from Chicago, so we naturally started working together. an artist’s work in a deeper conceptual context, something greater than It takes doers to push the culture forward, so I resonate with anyone fashion or art comes out. -

FASHION IS STILL MADONNA's PASSION Final 6.7.2012 1030Am

FASHION IS STILL MADONNA’S PASSION LOS ANGELES, CA (June 7, 2012) - Madonna’s MDNA Tour which opened in Tel Aviv on May 31 st includes over 700 costumes elements, six costume changes for the Material Girl and costume changes for the dancers with each song. The show is already being heralded as her most stunning and grandest extravaganza ever. Longtime Madonna stylist, Arianne Phillips, and her staff of 25 have put together an array of big name designers and emerging talent including Jean Paul Gaultier Couture, Brooks Brothers shirts and canes, Prada/MiuMiu shoes, club and street style innovators Jeremy Scott & Adidas, Dolce & Gabanna and several new creative partnerships, as well as her own Truth or Dare line encompassing lingerie and shoes that are scheduled to come out in the Fall. The Material Girl’s MDNA tour essentially runs the gamut from long time collaborators and new partners, fashion designers, retailers and artists along with dazzling elements of Swarovski crystals. “I see Madonna as one of the greatest performing artists and entertainers of our generation,” commented Phillips, a two time Oscar nominee, who has collaborated with Madonna for over l5 years and four tours. The wardrobe reflects new twists on familiar themes including spirituality, prophecy, light, super-vixen, Americana/sassy, majorette with a message, masculine, feminine, redemption and celebration. With styles including Truth or Dare lingerie with crosses, colorful metal mesh tee shirts, specially designed accessories including gargoyle and bunny masks, Brooks Brothers shirts and canes, swords, gun holsters, jeweled accessories, mirrored track suits, Lord of War tee shirts, Phillips designed Joan of Arc ensembles, a majorette costume with a l940’s inspired silhouette and Shaolin warrior costumes, fashionistas will easily find a wide range of styles and likely some new trends. -

The Ethics of the International Display of Fashion in the Museum, 49 Case W

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 49 | Issue 1 2017 The thicE s of the International Display of Fashion in the Museum Felicia Caponigri Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Felicia Caponigri, The Ethics of the International Display of Fashion in the Museum, 49 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 135 (2017) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol49/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law 49(2017) THE ETHICS OF THE INTERNATIONAL DISPLAY OF FASHION IN THE MUSEUM Felicia Caponigri* CONTENTS I. Introduction................................................................................135 II. Fashion as Cultural Heritage...................................................138 III. The International Council of Museums and its Code of Ethics .....................................................................................144 A. The International Council of Museums’ Code of Ethics provides general principles of international law...........................................146 B. The standard that when there is a conflict of interest between the museum and an individual, the interests of the museum should prevail seems likely to become a rule of customary international law .................................................................................................149 IV. China: Through the Looking Glass at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.......................................................................162 A. Anna Wintour and Condé Nast: A broad museum interest for trustees and a semi-broad museum interest for sponsors .................164 B. -

Marcas E Editoriais De Moda Em Diferentes Nichos De Revistas Especializadas

UNIVERSIDADE DA BEIRA INTERIOR Engenharia Marcas e Editoriais de Moda em Diferentes Nichos de Revistas Especializadas O caso Vogue, i-D e Dazed & Confused Joana Miguel Ramires Dissertação para obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Design de Moda (2º ciclo de estudos) Orientador: Prof. Doutora Maria Madalena Rocha Pereira Covilhã, Outubro de 2012 Marcas e Editoriais de Moda em Diferentes Nichos de Revistas Especializadas II Marcas e Editoriais de Moda em Diferentes Nichos de Revistas Especializadas Agradecimentos Ao longo do percurso que resultou na realização deste trabalho, foram várias as pessoas que ajudaram a desenvolve-lo e que disponibilizaram o seu apoio e amizade. Desta forma, o primeiro agradecimento vai para a orientadora, Professora Doutora Maria Madalena Rocha Pereira, que desde o início foi incansável. Agradeço-lhe pela disponibilidade, compreensão, por me ter guiado da melhor forma por entre todas as dúvidas e problemas que foram surgindo, e por fim, pela força de vontade e entusiamo que me transmitiu. A todos os técnicos e colaboradores dos laboratórios e ateliês do departamento de engenharia têxtil da Universidade da Beira Interior agradeço o seu apoio e os ensinamentos transmitidos ao longo da minha vida académica. Agradeço em especial á D. Lucinda pela sua amizade, e pelo seu apoio constante ao longo destes anos. Às duas pessoas mais importantes da minha vida, pai e mãe agradeço do fundo do coração por todo o amor, carinho, compreensão, e por todos os sacrifícios que fizeram, de modo a me permitirem chegar ao final de mais esta etapa de estudos. Aos meus avós e restante família que também têm sido um pilar fundamental na minha vida a todos os níveis, os meus sinceros agradecimentos. -

Download The

The House of an Artist Recognized as one of the world’s most celebrated perfumers, Francis Kurkdjian has created over the past 20 years more than 40 world famous perfumes for fashion houses such as Dior, Kenzo, Burberry, Elie Saab, Armani, Narciso Rodriguez… Instead of settling comfortably into the beginnings of a brilliant career started with the creation of ”Le Mâle” for Jean Paul Gaultier in 1993, he opened the pathways to a new vision. He was the first in 2001 to open his bespoke fragrances atelier, going against the trend of perfume democratization. He has created gigantic olfactory installations in emblematic spaces, making people dream with his ephemeral and spectacular perfumed performances. All this, while continuing to create perfumes for world famous fashion brands and designers, as fresh as ever. Maison Francis Kurkdjian was a natural move in 2009, born from the encounter between Francis Kurkdjian and Marc Chaya, Co-founder and President of the fragrance house. Together, they fulfilled their desire for a sensual, generous and multi-facetted landscape of free expression, creating a new emblem of French know-how and lifestyle. A high-end fragrance house Maison Francis Kurkdjian’s unique personality is fostered by the creative power of a man who has a taste for precision. The Maison is guided by enchanting yet precise codes: purity, sophistication, timelessness and the boldness of a classicism reinvented. Designed in the tradition of luxury French perfumery, the Maison Francis Kurkdjian collection advocates nevertheless a contemporary vision of the art of creating and wearing perfume. Francis Kurkdjian creations were sketched like a fragrance wardrobe, with myriad facets of emotions. -

Alexander Mcqueen: El Horror Y La Belleza

en el Metropolitan Museum of Art de Nueva York en 2011. (Fotografía: Charles Eshelman / FilmMagic) (Fotografía: en 2011. York en el Metropolitan Museum of Art de Nueva Savage BeautySavage Una pieza de la exposición Alexander McQueen: el horror y la belleza Héctor Antonio Sánchez 54 | casa del tiempo A mediados de febrero de 2010, durante la entrega de los Brit Awards, Lady Gaga presentó un homenaje al diseñador Alexander McQueen, cuya muerte fuera divul- gada en medios apenas una semana antes. La cantante, sentada al piano, vestía una singular máscara con motivos florales que se extendía hacia la parte superior de su cabeza, hasta una monumental peluca à la Marie-Antoinette: a sus espaldas se erguía una estatua que la emulaba, una figura femenina con una falda en forma de piano- la y los icónicos armadillo shoes de McQueen que la misma cantante popularizara en videos musicales. La extravagante interpretación recordaba por igual algunos momentos de Elton John y David Bowie, quienes hace tanto tiempo exploraron las posibles y fructífe- ras alianzas entre la moda, la música y el espectáculo, y recordaba particularmente —aunque con menor fortuna, como en una reelaboración minimalista y reduc- tiva— cierta edición de los MTV Video Music Awards donde, acompañada de su corte de bailarines, Madonna presentó “Vogue” ataviada en un exuberante vestido propio de la moda de Versalles. No vanamente asociados al camaleón, Madonna y Bowie han abrazado como pocos las posibilidades de la imagen: el vínculo entre la moda y la música popular ha creado —sobre todo en nuestros días— una plétora de banalidad, tontería y aun vulgaridad, pero en sus mejores momentos ha logrado visiones que colindan con el arte. -

Media Guide 1 Contents

Tuesday 19th - Saturday 23rd June 2018 MEDIA GUIDE 1 CONTENTS WELCOME TO ROYAL ASCOT FROM HER MAJESTY’S REPRESENTATIVE 4 VISITOR INFORMATION 5 RACING AT ROYAL ASCOT 6 RECORD PRIZE MONEY OF £13.45 MILLION AT ASCOT IN 2018 7 ROYAL ASCOT 2017 REVIEW 8 ROYAL ASCOT 2018 ORDER OF RUNNING AND PRIZE MONEY 10 ROYAL ASCOT GROUP I ENTRIES 12 A GLOBAL EVENT: ROYAL ASCOT’S RACE PROGRAMME MILESTONES 14 THE WEATHERBYS HAMILTON STAYERS’ MILLION 16 FOUR BREEDERS’ CUP CHALLENGE RACES TO BE HELD AT ROYAL ASCOT IN 2018 17 WORLD HORSE RACING LAUNCHES THE ULTIMATE DIGITAL RACING EXPERIENCE 18 CUSTOMERS INVITED TO BET WITH ASCOT 19 2018 GOFFS LONDON SALE GIVEN A NEW LOOK AT SAME ADDRESS 20 THE ROAD TO QIPCO BRITISH CHAMPIONS DAY 21 THE BELL ÉPOQUE 22 VETERINARY FACILITIES, EQUINE AND JOCKEYS’ FACILITIES 26 CHRIS STICKELS, CLERK OF THE COURSE 27 BROADCASTERS AT ROYAL ASCOT 28 NEW AT ROYAL ASCOT 30 COMMONWEALTH FASHION EXCHANGE 31 ASCOT RACECOURSE SUPPORTS 32 SCULPTURES 34 SHOPPING: THE COLLECTION 39 PARTNERS & SUPPLIERS 42 ASCOT’S OFFICIAL PARTNERS 43 ASCOT’S OFFICIAL SPONSORS AND SUPPLIERS 46 FASHION & DRESS CODE 50 ASCOT LAUNCHES THE SEVENTH ANNUAL ROYAL ASCOT STYLE GUIDE 51 THE HISTORY OF FASHION AT ROYAL ASCOT - KEY DATES 52 THE ROYAL ASCOT MILLINERY COLLECTIVE 2018 54 ROYAL ASCOT DRESS CODE 56 FINE DINING AT ROYAL ASCOT 58 FINE DINING AT ROYAL ASCOT CONTINUES TO DIVERSIFY AND DELIGHT 59 ASCOT HISTORY 66 ASCOT STORIES AND OTHER PROMOTIONAL FILMS 67 ROYAL ASCOT - THE ROYAL PROCESSION 68 THE BOWLER HAT AND ASCOT 71 ROYAL ASCOT FACTS AND FIGURES 72 ASCOT RACECOURSE -

Andrew Bolton, Il Nuovo Responsabile Del Costume Institute Del Metropolitan Di New York, Ci Spiega Il Suo Senso Della Moda

Andrew Bolton, il nuovo responsabile del Costume Institute del Metropolitan di New York, ci spiega il suo senso della moda. E come creare sintesi elettriche tra innovazione e tradizione, lasciando gli oggetti liberi di raccontare. L’ a r t e d e l l a seduzione Testo di Foto di OLIVIA FINCAto FRANCESCO LAGNESE DATING Crossover «Essenziale è sedurre visivamente il visitatore. Solo quando è sedotto, potrà leggere i signifi- cati dietro un oggetto» i visitatori» precisa il curatore, «Solo quando il pubblico è sedotto, potrà leggere i significati dietro un oggetto, oppure se ne andrà, con una memoria vivida». La mostra Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty del 2011, co-curata con il suo predecessore Mr. Koda, ha attratto (ed emo- zionato) più di 650mila visitatori. Racconta Bolton: «Fu inaugurata a un anno dal suicidio di McQueen, c’era ancora un incredibile senso di amarezza. Gli abiti erano imbevuti della sua intensità. Trascinavano gli spettatori dalla gioia alla rabbia, dalla quiete al dolore. Sublime». Per il nuovo responsabile del Costume Institute, intrattenimento ed educazione devono convivere, sti- molando l’immaginazione. Come il maestro Harold Koda anche Andrew Bolton indaga il presente con la lente del passato, creando sintesi elettriche tra novità e tradizione e lasciando gli oggetti liberi di parlare e, come dice lui, respirare. Il curatore arrivò dall’Inghilterra a New York nel 2002, con solo due anni di esperienza nel mondo della moda. Cresciuto in un piccolo villaggio in Lancashi- re, dopo la laurea in antropologia all’università di East Anglia, conseguì un master in Non-Western Art. La sua carriera accademica iniziò al dipartimento East Asia del Victoria and Albert Museum di Londra: «Mi innamorai In apertura, Andrew Bol- ton al The Met (completo dell’idea di raccontare storie attraverso gli oggetti. -

The First Monday in May

A Magnolia Pictures, Relativity Studios & Planned Projects In Association with Condé Nast Entertainment, Mediaweaver Entertainment & Sarah Arison Productions Present A Fabiola Beracasa Beckman Production THE FIRST MONDAY IN MAY A film by Andrew Rossi 91 minutes Official Selection 2016 Tribeca Film Festival – Opening Night World Premiere Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR 1352 Dundas St. West Tel: 416-488-4436 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1Y2 Fax: 416-488-8438 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com @MongrelMedia MongrelMedia 1 An unprecedented look behind the scenes of two of New York’s premier cultural events, The First Monday in May follows the creation of “China: Through The Looking Glass,” the most attended fashion exhibition in the history of The Costume Institute at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the 2015 Met Gala, the star-studded fundraiser that celebrates the opening of the exhibition. Acclaimed filmmaker Andrew Rossi (Page One: Inside the New York Times) follows Anna Wintour, Artistic Director of Condé Nast and editor-in-chief of Vogue magazine and longtime chair of the Met Gala, and Andrew Bolton, the iconoclastic curator who conceived the groundbreaking show, for eight months as they prepare for an evening they hope will take the worlds of art and fashion by storm. Documenting one of the most exclusive parties in the world side-by-side with an exhibition that drew more than three-quarters of a million visitors during its four-month run, The First Monday in May is a captivating portrait of the private side of a pair of high-profile public events. -

Christian Dior Exhibition in the UK

News Release Sunday 1 July 2018 V&A announces largest ever Christian Dior exhibition in the UK Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams The Sainsbury Gallery 2 February – 14 July 2019 vam.ac.uk | #DesignerofDreams “There is no other country in the world, besides my own, whose way of life I like so much. I love English traditions, English politeness, English architecture. I even love English cooking.” Christian Dior In February 2019, the V&A will open the largest and most comprehensive exhibition ever staged in the UK on the House of Dior – the museum’s biggest fashion exhibition since Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty in 2015. Spanning 1947 to the present day, Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams will trace the history and impact of one of the 20th century’s most influential couturiers, and the six artistic directors who have succeeded him, to explore the enduring influence of the fashion house. Based on the major exhibition Christian Dior: Couturier du Rêve, organised by the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, the exhibition will be reimagined for the V&A. A brand-new section will, for the first time, explore the designer’s fascination with British culture. Dior admired the grandeur of the great houses and gardens of Britain, as well as British-designed ocean liners, including the Queen Mary. He also had a preference for Savile Row suits. In 1947, he hosted his first UK fashion show at London’s Savoy Hotel, and in 1952 established Christian Dior London. This exhibition will investigate Dior’s creative collaborations with influential British manufacturers, and his most notable British clients, from author Nancy Mitford to ballet dancer Margot Fonteyn.