A Performance Evaluation of Dynamical Downscaling of Precipitation Over Northern California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Point Downscaling of Surface Wind Speed for Forecast Applications

MARCH 2018 T A N G A N D B A S S I L L 659 Point Downscaling of Surface Wind Speed for Forecast Applications BRIAN H. TANG Department of Atmospheric and Environmental Sciences, University at Albany, State University of New York, Albany, New York NICK P. BASSILL New York State Mesonet, Albany, New York (Manuscript received 23 May 2017, in final form 26 December 2017) ABSTRACT A statistical downscaling algorithm is introduced to forecast surface wind speed at a location. The down- scaling algorithm consists of resolved and unresolved components to yield a time series of synthetic wind speeds at high time resolution. The resolved component is a bias-corrected numerical weather prediction model forecast of the 10-m wind speed at the location. The unresolved component is a simulated time series of the high-frequency component of the wind speed that is trained to match the variance and power spectral density of wind observations at the location. Because of the stochastic nature of the unresolved wind speed, the downscaling algorithm may be repeated to yield an ensemble of synthetic wind speeds. The ensemble may be used to generate probabilistic predictions of the sustained wind speed or wind gusts. Verification of the synthetic winds produced by the downscaling algorithm indicates that it can accurately predict various fea- tures of the observed wind, such as the probability distribution function of wind speeds, the power spectral density, daily maximum wind gust, and daily maximum sustained wind speed. Thus, the downscaling algo- rithm may be broadly applicable to any application that requires a computationally efficient, accurate way of generating probabilistic forecasts of wind speed at various time averages or forecast horizons. -

Off-Line Algorithm for Calculation of Vertical Tracer Transport in The

EGU Journal Logos (RGB) Open Access Open Access Open Access Advances in Annales Nonlinear Processes Geosciences Geophysicae in Geophysics Open Access Open Access Natural Hazards Natural Hazards and Earth System and Earth System Sciences Sciences Discussions Open Access Open Access Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 1093–1114, 2013 Atmospheric Atmospheric www.atmos-chem-phys.net/13/1093/2013/ doi:10.5194/acp-13-1093-2013 Chemistry Chemistry © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. and Physics and Physics Discussions Open Access Open Access Atmospheric Atmospheric Measurement Measurement Techniques Techniques Off-line algorithm for calculation of vertical tracer transport in the Discussions Open Access troposphere due to deep convection Open Access Biogeosciences 1,2 1 3,4,5 6 7 8 Biogeosciences9 10 D. A. Belikov , S. Maksyutov , M. Krol , A. Fraser , M. Rigby , H. Bian , A. Agusti-Panareda , D. Bergmann , Discussions P. Bousquet11, P. Cameron-Smith10, M. P. Chipperfield12, A. Fortems-Cheiney11, E. Gloor12, K. Haynes13,14, P. Hess15, S. Houweling3,4, S. R. Kawa8, R. M. Law14, Z. Loh14, L. Meng16, P. I. Palmer6, P. K. Patra17, R. G. Prinn18, R. Saito17, 12 Open Access and C. Wilson Open Access 1Center for Global Environmental Research, National Institute for Environmental Studies, 16-2 Onogawa,Climate Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Climate 305-8506, Japan of the Past 2 of the Past Division for Polar Research, National Institute of Polar Research, 10-3, Midoricho, Tachikawa, Tokyo 190-8518, Japan Discussions 3SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research, Sorbonnelaan -

Climate Scenarios Developed from Statistical Downscaling Methods. IPCC

Guidelines for Use of Climate Scenarios Developed from Statistical Downscaling Methods RL Wilby1,2, SP Charles3, E Zorita4, B Timbal5, P Whetton6, LO Mearns7 1Environment Agency of England and Wales, UK 2King’s College London, UK 3CSIRO Land and Water, Australia 4GKSS, Germany 5Bureau of Meteorology, Australia 6CSIRO Atmospheric Research, Australia 7National Center for Atmospheric Research, USA August 2004 Document history The Guidelines for Use of Climate Scenarios Developed from Statistical Downscaling Methods constitutes “Supporting material” of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (as defined in the Procedures for the Preparation, Review, Acceptance, Adoption, Approval, and Publication of IPCC Reports). The Guidelines were prepared for consideration by the IPCC at the request of its Task Group on Data and Scenario Support for Impacts and Climate Analysis (TGICA). This supporting material has not been subject to the formal intergovernmental IPCC review processes. The first draft of the Guidelines was produced by Rob Wilby (Environment Agency of England and Wales) in March 2003. Subsequently, Steven Charles, Penny Whetton, and Eduardo Zorito provided additional materials and feedback that were incorporated by June 2003. Revisions were made in the light of comments received from Elaine Barrow and John Mitchell in November 2003 – most notably the inclusion of a worked case study. Further comments were received from Penny Whetton and Steven Charles in February 2004. Bruce Hewitson, Jose Marengo, Linda Mearns, and Tim Carter reviewed the Guidelines on behalf of the Task Group on Data and Scenario Support for Impacts and Climate Analysis (TGICA), and the final version was published in August 2004. 2/27 Guidelines for Use of Climate Scenarios Developed from Statistical Downscaling Methods 1. -

Verification of a Multimodel Storm Surge Ensemble Around New York City and Long Island for the Cool Season

922 WEATHERANDFORECASTING V OLUME 26 Verification of a Multimodel Storm Surge Ensemble around New York City and Long Island for the Cool Season TOM DI LIBERTO * AND BRIAN A. C OLLE School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York NICKITAS GEORGAS AND ALAN F. B LUMBERG Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken, New Jersey ARTHUR A. T AYLOR Meteorological Development Laboratory, NOAA/NWS, Office of Science and Technology, Silver Spring, Maryland (Manuscript received 21 November 2010, in final form 27 June 2011) ABSTRACT Three real-time storm surge forecasting systems [the eight-member Stony Brook ensemble (SBSS), the Stevens Institute of Technology’s New York Harbor Observing and Prediction System (SIT-NYHOPS), and the NOAA Extratropical Storm Surge (NOAA-ET) model] are verified for 74 available days during the 2007–08 and 2008–09 cool seasons for five stations around the New York City–Long Island region. For the raw storm surge forecasts, the SIT-NYHOPS model has the lowest root-mean-square errors (RMSEs) on average, while the NOAA-ET has the largest RMSEs after hour 24 as a result of a relatively large negative surge bias. The SIT-NYHOPS and SBSS also have a slight negative surge bias after hour 24. Many of the underpredicted surges in the SBSS ensemble are associated with large waves at an offshore buoy, thus illustrating the potential importance of nearshore wave breaking (radiation stresses) on the surge pre- dictions. A bias correction using the last 5 days of predictions (BC) removes most of the surge bias in the NOAA-ET model, with the NOAA-ET-BC having a similar level of accuracy as the SIT-NYHOPS-BC for positive surges. -

Seasonal and Diurnal Performance of Daily Forecasts with WRF V3.8.1 Over the United Arab Emirates

Geosci. Model Dev., 14, 1615–1637, 2021 https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-14-1615-2021 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Seasonal and diurnal performance of daily forecasts with WRF V3.8.1 over the United Arab Emirates Oliver Branch1, Thomas Schwitalla1, Marouane Temimi2, Ricardo Fonseca3, Narendra Nelli3, Michael Weston3, Josipa Milovac4, and Volker Wulfmeyer1 1Institute of Physics and Meteorology, University of Hohenheim, 70593 Stuttgart, Germany 2Department of Civil, Environmental, and Ocean Engineering (CEOE), Stevens Institute of Technology, New Jersey, USA 3Khalifa University of Science and Technology, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates 4Meteorology Group, Instituto de Física de Cantabria, CSIC-University of Cantabria, Santander, Spain Correspondence: Oliver Branch ([email protected]) Received: 19 June 2020 – Discussion started: 1 September 2020 Revised: 10 February 2021 – Accepted: 11 February 2021 – Published: 19 March 2021 Abstract. Effective numerical weather forecasting is vital in T2 m bias and UV10 m bias, which may indicate issues in sim- arid regions like the United Arab Emirates (UAE) where ex- ulation of the daytime sea breeze. TD2 m biases tend to be treme events like heat waves, flash floods, and dust storms are more independent. severe. Hence, accurate forecasting of quantities like surface Studies such as these are vital for accurate assessment of temperatures and humidity is very important. To date, there WRF nowcasting performance and to identify model defi- have been few seasonal-to-annual scale verification studies ciencies. By combining sensitivity tests, process, and obser- with WRF at high spatial and temporal resolution. vational studies with seasonal verification, we can further im- This study employs a convection-permitting scale (2.7 km prove forecasting systems for the UAE. -

Downscaling of General Circulation Models for Regionalisation of Water

Climate Change Causes and Hydrologic Predictive Capabilities V.V. Srinivas Associate Professor Department of Civil Engineering Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore [email protected] 1 2 Overview of Presentation Climate Change Causes Effects of Climate Change Hydrologic Predictive Capabilities to Assess Impacts of Climate Change on Future Water Resources . GCMs and Downscaling Methods . Typical case studies Gaps where more research needs to be focused 3 Weather & Climate Weather Definition: Condition of the atmosphere at a particular place and time Time scale: Hours-to-days Spatial scale: Local to regional Climate Definition: Average pattern of weather over a period of time Time scale: Decadal-to-centuries and beyond Spatial scale: Regional to global Climate Change Variation in global and regional climates 4 Climate Change – Causes Variation in the solar output/radiation Sun-spots (dark patches) (11-years cycle) (Source: PhysicalGeography.net) Cyclic variation in Earth's orbital characteristics and tilt - three Milankovitch cycles . Change in the orbit shape (circular↔elliptical) (100,000 years cycle) . Changes in orbital timing of perihelion and aphelion – (26,000 years cycle) . Changes in the tilt (obliquity) of the Earth's axis of rotation (41,000 year cycle; oscillates between 22.1 and 24.5 degrees) 5 Climate Change - Causes Volcanic eruptions Ejected SO2 gas reacts with water vapor in stratosphere to form a dense optically bright haze layer that reduces the atmospheric transmission of incoming solar radiation Figure : Ash column generated by the eruption of Mount Pinatubo. (Source: U.S. Geological Survey). 6 Climate Change - Causes Variation in Atmospheric GHG concentration Global warming due to absorption of longwave radiation emitted from the Earth's surface Sources of GHGs . -

Downscaling Climate Modelling for High-Resolution Climate Information and Impact Assessment

HANDBOOK N°6 Seminar held in Lecce, Italy 9 - 20 March 2015 Euro South Mediterranean Initiative: Climate Resilient Societies Supported by Low Carbon Economies Downscaling Climate Modelling for High-Resolution Climate Information and Impact Assessment Project implemented by Project funded by the AGRICONSULTING CONSORTIUM EuropeanA project Union funded by Agriconsulting Agrer CMCC CIHEAM-IAM Bari the European Union d’Appolonia Pescares Typsa Sviluppo Globale 1. INTRODUCTION 2. DOWNSCALING SCENARIOS 3. SEASONAL FORECASTS 4. CONCEPTS & EXAMPLES 5. CONCLUSIONS 6. WEB LINKS 7. REFERENCES DISCLAIMER The information and views set out in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the offi- cial opinion of the European Union. Neither the European Union, its institutions and bodies, nor any person acting on their behalf, may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained herein. The content of the report is based on presentations de- livered by speakers at the seminars and discussions trig- gered by participants. Editors: The ClimaSouth team with contributions by Neil Ward (lead author), E. Bucchignani, M. Montesarchio, A. Zollo, G. Rianna, N. Mancosu, V. Bacciu (CMCC experts), and M. Todorovic (IAM-Bari). Concept: G.H. Mattravers Messana Graphic template: Zoi Environment Network Graphic design & layout: Raffaella Gemma Agriconsulting Consortium project directors: Ottavio Novelli / Barbara Giannuzzi Savelli ClimaSouth Team Leader: Bernardo Sala Project funded by the EuropeanA project Union funded by the European Union Acronyms | Disclaimer | CS website 2 1. INTRODUCTION 2. DOWNSCALING SCENARIOS 3. SEASONAL FORECASTS 4. CONCEPTS & EXAMPLES 5. CONCLUSIONS 6. WEB LINKS 7. REFERENCES FOREWORD The Mediterranean region has been identified as a cli- ernment, the private sector and civil society. -

Challenges in the Paleoclimatic Evolution of the Arctic and Subarctic Pacific Since the Last Glacial Period—The Sino–German

challenges Concept Paper Challenges in the Paleoclimatic Evolution of the Arctic and Subarctic Pacific since the Last Glacial Period—The Sino–German Pacific–Arctic Experiment (SiGePAX) Gerrit Lohmann 1,2,3,* , Lester Lembke-Jene 1 , Ralf Tiedemann 1,3,4, Xun Gong 1 , Patrick Scholz 1 , Jianjun Zou 5,6 and Xuefa Shi 5,6 1 Alfred-Wegener-Institut Helmholtz-Zentrum für Polar- und Meeresforschung Bremerhaven, 27570 Bremerhaven, Germany; [email protected] (L.L.-J.); [email protected] (R.T.); [email protected] (X.G.); [email protected] (P.S.) 2 Department of Environmental Physics, University of Bremen, 28359 Bremen, Germany 3 MARUM Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen, 28359 Bremen, Germany 4 Department of Geosciences, University of Bremen, 28359 Bremen, Germany 5 First Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, Qingdao 266061, China; zoujianjun@fio.org.cn (J.Z.); xfshi@fio.org.cn (X.S.) 6 Pilot National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao 266061, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 24 December 2018; Accepted: 15 January 2019; Published: 24 January 2019 Abstract: Arctic and subarctic regions are sensitive to climate change and, reversely, provide dramatic feedbacks to the global climate. With a focus on discovering paleoclimate and paleoceanographic evolution in the Arctic and Northwest Pacific Oceans during the last 20,000 years, we proposed this German–Sino cooperation program according to the announcement “Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) of the Federal Republic of Germany for a German–Sino cooperation program in the marine and polar research”. Our proposed program integrates the advantages of the Arctic and Subarctic marine sediment studies in AWI (Alfred Wegener Institute) and FIO (First Institute of Oceanography). -

Cccma CMIP6 Model Updates

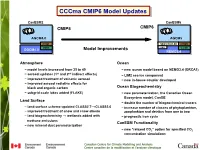

CCCma CMIP6 Model Updates CanESM2! CanESM5! CMIP5 CMIP6 AGCM4.0! AGCM5! CTEM NEW COUPLER CTEM5 CMOC LIM2 CanOE OGCM4.0! Model Improvements NEMO3.4! Atmosphere Ocean − model levels increased from 35 to 49 − new ocean model based on NEMO3.4 (ORCA1) st nd − aerosol updates (1 and 2 indirect effects) − LIM2 sea-ice component − improved treatment of volcanic aerosol − new in-house coupler developed − improved aerosol radiative effects for black and organic carbon Ocean Biogeochemistry − subgrid scale lakes added (FLAKE) − new parameterization, the Canadian Ocean Ecosystem model, CanOE Land Surface − double the number of biogeochemical tracers − land-surface scheme updated CLASS2.7→CLASS3.6 − increase number of classes of phytoplankton, − improved treatment of snow and snow albedo zooplankton and detritus from one to two − land biogeochemistry → wetlands added with − prognostic iron cycle methane emissions CanESM Functionality − new mineral dust parameterization − new “relaxed CO2” option for specified CO2 concentration simulations Other issues: 1. We are currently in the process of migrating to a new supercomputing system – being installed now and should be running on it over the next few months. 2. Global climate model development is integrated with development of operational seasonal prediction system, decadal prediction system, and regional climate downscaling system. 3. We are also increasingly involved in aspects of ‘climate services’ – providing multi-model climate scenario information to impact and adaptation users, decision-makers, -

A Numerical Case Study of Upper Boundary Condition in MM5 Over

A CASE STUDY OF THE IMPACT OF THE UPPER BOUNDARY CONDITION IN POLAR MM5 SIMULATIONS OVER ANTARCTICA Helin Wei1, David H. Bromwich1, 2 , Le-Sheng Bai1, Ying-Hwa Kuo3, and Tae Kwon Wee3 1Polar Meteorology Group, Byrd Polar Research Center, The Ohio State University 2Atmospheric Sciences Program, Department of Geography, The Ohio State University 3MMM Division, National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, Colorado 1. Introduction generally applied numerical models because the 1In limited area modeling, the upper boundary vertical wavenumber and frequency of the radiated condition was not addressed extensively until waves must be specified. Second, it also requires nonhydrostatic models became widely available a relatively deep model domain so that the vertical for numerical weather prediction. Ideally, the radiation of gravity wave energy is of secondary boundary condition should be imposed in such importance at the model top, otherwise the way that makes the flow behave as if the spurious momentum flux is not negligible (Klemp boundaries were not there. and Durran, 1983). In the past, the rigid lid upper boundary Another prominent scheme is the absorbing condition was utilized because it purportedly upper boundary condition. It is designed to damp eliminated rapidly moving external gravity waves out the vertically propogating waves within an from the solutions, thereby permitting longer time upper boundary buffer zone before they reach the dp top boundary by using smoothing, filtering or some steps. This condition requires ω = = 0 at the other approach, such as adding frictional terms to dt model momentum equations. model top. The effectiveness of this approach has Previous studies show that the radiation and been demonstrated when the model top is set far absorbing upper boundary conditions reduce the above from the region of interest or the advective wave reflection to a great extent, however little effects are dominant in comparison to the vertical work has been done to investigate how they propogation of internal gravity wave energy. -

Future Crop Yield Projections Using a Multi-Model Set of Regional Climate Models and a Plausible Adaptation Practice in the Southeast United States

atmosphere Article Future Crop Yield Projections Using a Multi-model Set of Regional Climate Models and a Plausible Adaptation Practice in the Southeast United States D. W. Shin 1, Steven Cocke 1, Guillermo A. Baigorria 2, Consuelo C. Romero 2, Baek-Min Kim 3 and Ki-Young Kim 4,* 1 Center for Ocean-Atmospheric Prediction Studies, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306-2840, USA; [email protected] (D.W.S.); [email protected] (S.C.) 2 Next Season Systems LLC, Lincoln, NE 68506, USA; [email protected] (G.A.B.); [email protected] (C.C.R.) 3 Department of Environmental Atmospheric Sciences, Pukyung National University, Busan 48513, Korea; [email protected] 4 4D Solution Co. Ltd., Seoul 08511, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-2-878-0126 Received: 28 October 2020; Accepted: 27 November 2020; Published: 30 November 2020 Abstract: Since maize, peanut, and cotton are economically valuable crops in the southeast United States, their yield amount changes in a future climate are attention-grabbing statistics demanded by associated stakeholders and policymakers. The Crop System Modeling—Decision Support System for Agrotechnology Transfer (CSM-DSSAT) models of maize, peanut, and cotton are, respectively, driven by the North American Regional Climate Change Assessment Program (NARCCAP) Phase II regional climate models to estimate current (1971–2000) and future (2041–2070) crop yield amounts. In particular, the future weather/climate data are based on the Special Report on Emission Scenarios (SRES) A2 emissions scenario. The NARCCAP realizations show on average that there will be large temperature increases (~2.7 C) and minor rainfall decreases (~ 0.10 mm/day) with pattern shifts ◦ − in the southeast United States. -

Statistical Downscaling

Statistical downscaling of the Community Climate System Model (CCSM) monthly temperature and precipitation projections White Paper by Tim Hoar and Doug Nychka (IMAGe/NCAR) April 2008 Statistical Downscaling The outputs from the Community Climate System Model (CCSM) may be relatively coarse for applications on regional and local scales. This results from an attempt to balance the computational cost of producing many long simulations and the cost of running at higher resolutions. W hile useful for their intended purpose, it is also desirable to use this information at a local scale. The spatial resolution of climate change datasets generated from the CCSM runs is approximately 1.4 x 1.4 degrees (Figure 1). Figure 1: Centroids of CCSM grid cells at approximately 1.4 degree spatial resolution Downscaling is the general name for a procedure to take information known at large scales to make predictions at local scales. Statistical downscaling is a two-step process consisting of i) the development of statistical relationships between local climate variables (e.g., surface air temperature and precipitation) and large-scale predictors (e.g., pressure fields), and ii) the application of such relationships to the output of Global Climate Model (GCM) experiments to simulate local climate characteristics in the future. Statistical downscaling may be used in climate impacts assessment at regional and local scales and when suitable observed data are available to derive the statistical relationships. A variety of statistical downscaling methods have been developed, ranging from seasonal and monthly to daily and hourly climate and weather simulations on a local scale. The majority of methods have been developed for the US, European and Japanese locations, where long-term observed data are available for model calibration and verification.