Redeployment by Phil Klay Reading Guide Discussion Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11 Th Grade American Literature Summer Assignment (20192020 School Y Ear)

6/26/2019 American Lit Summer Reading 2019-20 - Google Docs 11 th Grade American Literature Summer Assignment (20192020 School Y ear) Welcome to American Literature! This summer assignment is meant to keep your reading and writing skills fresh. You should choose carefully —select books that will be interesting and enjoyable for you. Any assignments that do not follow directions exactly will not be accepted. This assignment is due Friday, August 16, 2019 to your American Literature Teacher. This will count as your first formative grade and be used as a diagnostic for your writing ability. Directions: For your summer assignment, please choose o ne of the following books to read. You can choose if your book is Fiction or Nonfiction. Fiction Choices Nonfiction Choices Catch 22 by Joseph Heller The satirical story of a WWII soldier who The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace by Jeff Hobbs. An account thinks everyone is trying to kill him and hatches plot after plot to keep of a young African‑American man who escaped Newark, NJ, to attend from having to fly planes again. Yale, but still faced the dangers of the streets when he returned is, Bastard Out of Carolina by Dorothy Allison The story of an abusive “nuanced and shattering” ( People ) and “mesmeric” ( The New York Southern childhood. Times Book Review ) . The Known World by Edward P. Jones The story of a black, slave Outliers / Blink / The Tipping Point by Malcolm Gladwell Fascinating owning family. statistical studies of everyday phenomena. For Whom the Bell Tolls by Ernest Hemingway A young American The Hot Zone: A Terrifying True Story by Richard Preston There is an anti‑fascist guerilla in the Spanish civil war falls in love with a complex outbreak of ebola virus in an American lab, and other stories of germs woman. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

Award Winners

RITA Awards (Romance) Silent in the Grave / Deanna Ray- bourn (2008) Award Tribute / Nora Roberts (2009) The Lost Recipe for Happiness / Barbara O'Neal (2010) Winners Welcome to Harmony / Jodi Thomas (2011) How to Bake a Perfect Life / Barbara O'Neal (2012) The Haunting of Maddy Clare / Simone St. James (2013) Look for the Award Winner la- bel when browsing! Oshkosh Public Library 106 Washington Ave. Oshkosh, WI 54901 Phone: 920.236.5205 E-mail: Nothing listed here sound inter- [email protected] Here are some reading suggestions to esting? help you complete the “Award Winner” square on your Summer Reading Bingo Ask the Reference Staff for card! even more awards and winners! 2016 National Book Award (Literary) The Fifth Season / NK Jemisin Pulitzer Prize (Literary) Fiction (2016) Fiction The Echo Maker / Richard Powers (2006) Gilead / Marilynn Robinson (2005) Tree of Smoke / Dennis Johnson (2007) Agatha Awards (Mystery) March /Geraldine Brooks (2006) Shadow Country / Peter Matthiessen (2008) The Virgin of Small Plains /Nancy The Road /Cormac McCarthy (2007) Let the Great World Spin / Colum McCann Pickard (2006) The Brief and Wonderous Life of Os- (2009) A Fatal Grace /Louise Penny car Wao /Junot Diaz (2008) Lord of Misrule / Jaimy Gordon (2010) (2007) Olive Kitteridge / Elizabeth Strout Salvage the Bones / Jesmyn Ward (2011) The Cruelest Month /Louise Penny (2009) The Round House / Louise Erdrich (2012) (2008) Tinker / Paul Harding (2010) The Good Lord Bird / James McBride (2013) A Brutal Telling /Louise Penny A Visit -

Fire and Forget This Interview Was Generously Shared with the Common Reading Program by Perseus Publishing Group

Common Reading Program 2014 St. Cloud State University Teaching and Discussion Guide 2 Common Reading Program 2014| Guide Table of Contents I. Book Summary 3 II. A Talk with Matt 4-8 III. Iraq and Afghanistan War Timeline 9 IV. Map of Afghanistan 10 V. Map of Iraq 11 VI. Glossary 12 VII. Book Discussion and Facilitation guide 13-14 VIII. Teaching about wars in Iraq and Afghanistan 15 IX. Related Activities 16 X. National Veterans Resources and Support Organizations 17 XI. Local Veterans Resources and Support Organizations 18 XII. Related Books 19 XIII. Documentaries 20 XIV. Feature Film Suggestions 21 3 Common Reading Program 2014| Guide Book Summary The stories aren't pretty and they aren't for the faint of heart. They are gritty, haunting, shocking—and unforgettable. Television reports, movies, newspapers, and blogs about the recent wars have offered snapshots of the fighting there. But this anthology brings us a chorus of powerful storytellers—some of the first bards from our recent wars, emerging voices and new talents—telling the kind of panoramic truth that only fiction can offer. What makes these stories even more remarkable is that all of them are written by men and women whose lives were directly engaged in the wars—soldiers, Marines, and an army spouse. Featuring a forward by National Book Award-winner Colum McCann, this anthology spans every era of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, from Baghdad to Brooklyn, from Kabul to Fort Hood. 4 Common Reading Program 2014| Guide A Talk with Matt Gallagher and Roy Scranton -Editors of Fire and Forget This interview was generously shared with the Common Reading Program by Perseus Publishing Group. -

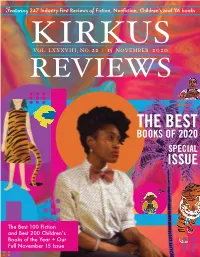

Kirkus Reviewer, Did for All of Us at the [email protected] Magazine Who Read It

Featuring 247 Industry-First Reviews of and YA books KIRVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 22 K | 15 NOVEMBERU 202S0 REVIEWS THE BEST BOOKS OF 2020 SPECIAL ISSUE The Best 100 Fiction and Best 200 Childrenʼs Books of the Year + Our Full November 15 Issue from the editor’s desk: Peak Reading Experiences Chairman HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] John Paraskevas Editor-in-Chief No one needs to be reminded: 2020 has been a truly god-awful year. So, TOM BEER we’ll take our silver linings where we find them. At Kirkus, that means [email protected] Vice President of Marketing celebrating the great books we’ve read and reviewed since January—and SARAH KALINA there’s been no shortage of them, pandemic or no. [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor With this issue of the magazine, we begin to roll out our Best Books ERIC LIEBETRAU of 2020 coverage. Here you’ll find 100 of the year’s best fiction titles, 100 [email protected] Fiction Editor best picture books, and 100 best middle-grade releases, as selected by LAURIE MUCHNICK our editors. The next two issues will bring you the best nonfiction, young [email protected] Young Readers’ Editor adult, and Indie titles we covered this year. VICKY SMITH The launch of our Best Books of 2020 coverage is also an opportunity [email protected] Tom Beer Young Readers’ Editor for me to look back on my own reading and consider which titles wowed LAURA SIMEON me when I first encountered them—and which have stayed with me over the months. -

Education Page 14

Education Page 14 Monday and Tuesday lectures are in Orchestra Hall, and Wednesday and Thursday lectures are in Chautauqua Hall. The Chautauqua Prize Vearl Smith Historic 10:30 a.m., Monday: Redeployment: A Writer’s Journey with Phil Klay Preservation Workshop (Orchestra Hall) After World War I, Louis Simpson wrote: “To a foot-soldier, war is almost Supported by the Vearl Smith Memorial Endowment for Historic Preservation entirely physical. That is why some men, when they think about war, fall silent. 10:30 a.m., Wednesday: Discovering Ohio Architecture with Barbara Powers Language seems to falsify physical life and to betray those who have experi- (Chautauqua Hall) enced it absolutely—the dead.” Discover the richness and diversity of Ohio’s architecture. The sto- Yet, after every war, veterans have taken up the task of rendering the seem- ry of Ohio, from early settlement, through industrial expansion, to mod- ingly unimaginable into words. National Book Award-winning author and Iraq ern times, is reflected in its landmark buildings, urban centers, small towns War veteran Phil Klay will describe his experiences in the Marine Corps, and and the work of specific architects and builders. This program will dis- why he ultimately decided that writing about Iraq was a necessity. cuss broad architectural trends and characteristics of specific styles ex- Klay is a graduate of Dartmouth College and a amined within the context of 19th and 20th century Ohio. Understand- veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps. He served from ing and appreciating historic architecture is key to its preservation. Learn January 2007 to February 2008 in Iraq’s Anbar about the programs offered through the State Historic Preservation Office Province as a Public Affairs Officer. -

Award Winning Books

More Man Booker winners: 1995: Sabbath’s Theater by Philip Roth Man Booker Prize 1990: Possession by A. S. Byatt 1994: A Frolic of His Own 1989: Remains of the Day by William Gaddis 2017: Lincoln in the Bardo by Kazuo Ishiguro 1993: The Shipping News by Annie Proulx by George Saunders 1985: The Bone People by Keri Hulme 1992: All the Pretty Horses 2016: The Sellout by Paul Beatty 1984: Hotel du Lac by Anita Brookner by Cormac McCarthy 2015: A Brief History of Seven Killings 1982: Schindler’s List by Thomas Keneally 1991: Mating by Norman Rush by Marlon James 1981: Midnight’s Children 1990: Middle Passage by Charles Johnson 2014: The Narrow Road to the Deep by Salman Rushdie More National Book winners: North by Richard Flanagan 1985: White Noise by Don DeLillo 2013: Luminaries by Eleanor Catton 1983: The Color Purple by Alice Walker 2012: Bring Up the Bodies by Hilary Mantel 1982: Rabbit Is Rich by John Updike 2011: The Sense of an Ending National Book Award 1980: Sophie’s Choice by William Styron by Julian Barnes 1974: Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon 2010: The Finkler Question 2016: Underground Railroad by Howard Jacobson by Colson Whitehead 2009: Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel 2015: Fortune Smiles by Adam Johnson 2008: The White Tiger by Aravind Adiga 2014: Redeployment by Phil Klay 2007: The Gathering by Anne Enright 2013: Good Lord Bird by James McBride National Book Critics 2006: The Inheritance of Loss 2012: Round House by Louise Erdrich by Kiran Desai 2011: Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward Circle Award 2005: The Sea by John Banville 2010: Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon 2004: The Line of Beauty 2009: Let the Great World Spin 2016: LaRose by Louise Erdrich by Alan Hollinghurst by Colum McCann 2015: The Sellout by Paul Beatty 2003: Vernon God Little by D.B.C. -

AMERIŠKA DRŽAVNA NAGRADA ZA KNJIŽEVNOST Nagrajene Knjige, Ki

AMERIŠKA DRŽAVNA NAGRADA ZA KNJIŽEVNOST Nagrajene knjige, ki jih imamo v naši knjižnični zbirki, so označene debelejše: Roman/kratke zgodbe 2018 Sigrid Nunez: The Friend 2017 Jesmyn Ward: Sing, Unburied, Sing 2016 Colson Whitehead THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD 2015 Adam Johnson FORTUNE SMILES: STORIES 2014 Phil Klay REDEPLOYMENT 2013 James McBrid THE GOOD LORD BIRD 2012 Louise Erdrich THE ROUND HOUSE 2011 Jesmyn Ward SALVAGE THE BONES 2010 Jaimy Gordon LORD OF MISRULE 2009 Colum McCann LET THE GREAT WORLD SPIN (Naj se širni svet vrti, 2010) 2008 Peter Matthiessen SHADOW COUNTRY 2007 Denis Johnson TREE OF SMOKE 2006 Richard Powers THE ECHO MAKER 2005 William T. Vollmann EUROPE CENTRAL 2004 Lily Tuck THE NEWS FROM PARAGUAY 2003 Shirley Hazzard THE GREAT FIRE 2002 Julia Glass THREE JUNES 2001 Jonathan Franzen THE CORRECTIONS (Popravki, 2005) 2000 Susan Sontag IN AMERICA 1999 Ha Jin WAITING (Čakanje, 2008) 1998 Alice McDermott CHARMING BILLY 1997 Charles Frazier COLD MOUNTAIN 1996 Andrea Barrett SHIP FEVER AND OTHER STORIES 1995 Philip Roth SABBATH'S THEATER 1994 William Gaddis A FROLIC OF HIS OWN 1993 E. Annie Proulx THE SHIPPING NEWS (Ladijske novice, 2009; prev. Katarina Mahnič) 1992 Cormac McCarthy ALL THE PRETTY HORSES 1991 Norman Rush MATING 1990 Charles Johnson MIDDLE PASSAGE 1989 John Casey SPARTINA 1988 Pete Dexter PARIS TROUT 1987 Larry Heinemann PACO'S STORY 1986 Edgar Lawrence Doctorow WORLD'S FAIR 1985 Don DeLillo WHITE NOISE (Beli šum, 2003) 1984 Ellen Gilchrist VICTORY OVER JAPAN: A BOOK OF STORIES 1983 Alice Walker THE COLOR PURPLE -

Phil Klay Is Fairfield’S MFA Writer-In- Residence, a Boon for the Program’S Military Veterans Receiving Financial Aid

Redeployed to Write National Book Award-winner and former marine Phil Klay is Fairfield’s MFA writer-in- residence, a boon for the program’s military veterans receiving financial aid. by Alan Bisbort Down by Seaside Chapel on Enders Island, as the waves of “ I’m a Catholic the Atlantic Ocean lap over the coastal rocks behind him, Phil Klay talks writing with several military veterans who are writer who had a enrolled in Fairfield’s MFA creative writing program. Jesuit education, Winner of the National Book Award for his first collection of short stories, Redeployment (2014), Klay stands on the and the Jesuit glistening rocks with his back to the water while the students worldview played a form a semicircle around him. Participants in Fairfield’s MFA program come each big role in shaping semester for a 10-day residency on the island located off the who I am.” coast of Mystic, Conn., to live in the retreat’s guest rooms, — Phil Klay, author eat in the dining hall, and talk about their work. At the end of their time in this idyllic setting, the students head back to their respective homes to complete the semester’s curriculum under the mentorship of a writing program instructor. On this sweltering late July afternoon, Klay is relaxed as he walks the beautiful 11-acre grounds of Enders Island and talks about writing. “I’m a Catholic writer who had a Jesuit LEFT: Left: National Book education, and the Jesuit worldview played a big role in Award-winner Phil Klay who is serving as Fairfield’s MFA shaping who I am,” said Klay. -

Adult Fiction Winners Adult Fiction Winners Adult Fiction Winners

How is the National Book Award chosen? How is the National Book Award chosen? How is the National Book Award chosen? Books must be written by an American citizen and Books must be written by an American citizen and Books must be written by an American citizen and published by an American publisher between published by an American publisher between published by an American publisher between December 1 of the previous year and November 30 December 1 of the previous year and November 30 December 1 of the previous year and November 30 of the current year. Chosen by a panel of of the current year. Chosen by a panel of of the current year. Chosen by a panel of distinguished judges to represent the best writing distinguished judges to represent the best writing distinguished judges to represent the best writing of the category that year. of the category that year. of the category that year. Adult Fiction Winners Adult Fiction Winners Adult Fiction Winners 2017 Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward 2017 Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward 2017 Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward 2016 The Underground Railroad by Colson 2016 The Underground Railroad by Colson 2016 The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead Whitehead Whitehead 2015 Fortune Smiles by Adam Johnson 2015 Fortune Smiles by Adam Johnson 2015 Fortune Smiles by Adam Johnson 2014 Redeployment by Phil Klay 2014 Redeployment by Phil Klay 2014 Redeployment by Phil Klay 2013 The Good Lord Bird by James McBride 2013 The Good Lord Bird by James McBride 2013 The Good Lord Bird by James McBride 2012 -

Fiction Award Winners 2019

1989: Spartina by John Casey 2016: The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen National Book 1988: Paris Trout by Pete Dexter 2015: All the Light We Cannot See by A. Doerr 1987: Paco’s Story by Larry Heinemann 2014: The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt Award 1986: World’s Fair by E. L. Doctorow 2013: Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 1985: White Noise by Don DeLillo 2012: No prize awarded 2011: A Visit from the Goon Squad “Established in 1950, the National Book Award is an 1984: Victory Over Japan by Ellen Gilchrist by Jennifer Egan American literary prize administered by the National 1983: The Color Purple by Alice Walker 2010: Tinkers by Paul Harding Book Foundation, a nonprofit organization.” 1982: Rabbit Is Rich by John Updike 2009: Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout - from the National Book Foundation website. 1980: Sophie’s Choice by William Styron 2008: The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao 1979: Going After Cacciato by Tim O’Brien by Junot Diaz 2018: The Friend by Sigrid Nunez 1978: Blood Tie by Mary Lee Settle 2007: The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2017: Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward 1977: The Spectator Bird by Wallace Stegner 2006: March by Geraldine Brooks 2016: The Underground Railroad by Colson 1976: J.R. by William Gaddis 2005: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson Whitehead 1975: Dog Soldiers by Robert Stone 2004: The Known World by Edward P. Jones 2015: Fortune Smiles by Adam Johnson The Hair of Harold Roux 2003: Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2014: Redeployment by Phil Klay by Thomas Williams 2002: Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2013: Good Lord Bird by James McBride 1974: Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon 2001: The Amazing Adventures of 2012: Round House by Louise Erdrich 1973: Chimera by John Barth Kavalier and Clay by Michael Chabon 2011: Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward 1972: The Complete Stories 2000: Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 2010: Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon by Flannery O’Connor 1999: The Hours by Michael Cunningham 2009: Let the Great World Spin by Colum McCann 1971: Mr. -

Fiction Winners

1984: Victory Over Japan by Ellen Gilchrist 2005: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson National Book Award 1983: The Color Purple by Alice Walker 2004: The Known World 1982: Rabbit Is Rich by John Updike by Edward P. Jones 1980: Sophie’s Choice by William Styron 2003: Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2015: Fortune Smiles by Adam Johnson 2014: Redeployment by Phil Klay 1979: Going After Cacciato by Tim O’Brien 2002: Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2013: Good Lord Bird by James McBride 1978: Blood Tie by Mary Lee Settle 2001: The Amazing Adventures of 1977: The Spectator Bird by Wallace Stegner 2012: Round House by Louise Erdrich Kavalier and Clay 2011: Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward 1976: J.R. by William Gaddis by Michael Chabon 1975: Dog Soldiers by Robert Stone 2000: Interpreter of Maladies 2010: Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon 2009: Let the Great World Spin The Hair of Harold Roux by Jhumpa Lahiri by Colum McCann by Thomas Williams 1999: The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1974: Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon 1998: American Pastoral by Philip Roth 2008: Shadow Country by Peter Matthiessen 1973: Chimera by John Barth 1997: Martin Dressler: The Tale of an 1972: The Complete Stories 2007: Tree of Smoke by Denis Johnson American Dreamer 2006: The Echo Maker by Richard Powers by Flannery O’Connor by Steven Millhauser 1971: Mr. Sammler’s Planet by Saul Bellow 1996: Independence Day by Richard Ford 2005: Europe Central by William T. Volmann 1970: Them by Joyce Carol Oates 1995: The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 2004: The News from Paraguay 1969: Steps