Episode 146 DKA Recognition & ED Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clinical Versus Laboratory for Estimating of Dehydration Severity

Clinical versus laboratory for estimating of dehydration severity Majid Malaki Pediatric Health Research Center, Tabriz Medical University, Tabriz, Iran ABSTRACT Background: Acute gastroenteritis is a common cause of dehydration and precise estimation of dehydration Materials and Methods: D is a vital matter for clinical decisions. We try to find how much clinically diagnosed scales are compatible with ORIGINAL ARTICLE laboratory tests measures. uring 2 years 95 infants and children aged between 2 and 108 months entered to emergency room with acute gastroenteritis. They were categorized as mild, moderate and severe dehydration, their recorded laboratory tests include blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, venous blood gases values were expressedP by means ±95% of confidence intervalResult and compared by mann-whitney test in each groups with SPSS 16, sensitivity, specificity and likelihood ratio measured for defined cut off values in severe dehydration group, value less than 0.05 was significant. : Severe dehydration includes 3% Conclusionof all hospitalization: R due to dehydration. Laboratory tests cannot differentiate mild to moderate dehydration definietly but this difference is significant between severe to mild and severe to moderate dehydration. outine laboratory test are not generally helpful for dehydration severity estimation but they can be discriminate severe from mild or moderate dehydration exclusively. Creatinine higher than 0.9 mg/dl and BaseKey words deficit: beyond-16A are specific (90%) for severe dehydration estimation -

Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Hyperosmolar BMJ: First Published As 10.1136/Bmj.L1114 on 29 May 2019

STATE OF THE ART REVIEW Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj.l1114 on 29 May 2019. Downloaded from hyperglycemic syndrome: review of acute decompensated diabetes in adult patients Esra Karslioglu French,1 Amy C Donihi,2 Mary T Korytkowski1 1Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of ABSTRACT Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome (HHS) are life threatening 2University of Pittsburgh School of complications that occur in patients with diabetes. In addition to timely identification of the Pharmacy, Pittsburgh, PA, USA Correspondence to: M Korytkowski precipitating cause, the first step in acute management of these disorders includes aggressive [email protected] administration of intravenous fluids with appropriate replacement of electrolytes (primarily Cite this as: BMJ 2019;365:l1114 doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1114 potassium). In patients with diabetic ketoacidosis, this is always followed by administration Series explanation: State of the of insulin, usually via an intravenous insulin infusion that is continued until resolution of Art Reviews are commissioned on the basis of their relevance to ketonemia, but potentially via the subcutaneous route in mild cases. Careful monitoring academics and specialists in the US and internationally. For this reason by experienced physicians is needed during treatment for diabetic ketoacidosis and HHS. they are written predominantly by Common pitfalls in management include premature termination of intravenous insulin US authors therapy and insufficient timing or dosing of subcutaneous insulin before discontinuation of intravenous insulin. This review covers recommendations for acute management of diabetic ketoacidosis and HHS, the complications associated with these disorders, and methods for http://www.bmj.com/ preventing recurrence. -

The History of Carbon Monoxide Intoxication

medicina Review The History of Carbon Monoxide Intoxication Ioannis-Fivos Megas 1 , Justus P. Beier 2 and Gerrit Grieb 1,2,* 1 Department of Plastic Surgery and Hand Surgery, Gemeinschaftskrankenhaus Havelhoehe, Kladower Damm 221, 14089 Berlin, Germany; fi[email protected] 2 Burn Center, Department of Plastic Surgery and Hand Surgery, University Hospital RWTH Aachen, Pauwelsstrasse 30, 52074 Aachen, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Intoxication with carbon monoxide in organisms needing oxygen has probably existed on Earth as long as fire and its smoke. What was observed in antiquity and the Middle Ages, and usually ended fatally, was first successfully treated in the last century. Since then, diagnostics and treatments have undergone exciting developments, in particular specific treatments such as hyperbaric oxygen therapy. In this review, different historic aspects of the etiology, diagnosis and treatment of carbon monoxide intoxication are described and discussed. Keywords: carbon monoxide; CO intoxication; COHb; inhalation injury 1. Introduction and Overview Intoxication with carbon monoxide in organisms needing oxygen for survival has probably existed on Earth as long as fire and its smoke. Whenever the respiratory tract of living beings comes into contact with the smoke from a flame, CO intoxication and/or in- Citation: Megas, I.-F.; Beier, J.P.; halation injury may take place. Although the therapeutic potential of carbon monoxide has Grieb, G. The History of Carbon also been increasingly studied in recent history [1], the toxic effects historically dominate a Monoxide Intoxication. Medicina 2021, 57, 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/ much longer period of time. medicina57050400 As a colorless, odorless and tasteless gas, CO is produced by the incomplete combus- tion of hydrocarbons and poses an invisible danger. -

Pathophysiology of Acid Base Balance: the Theory Practice Relationship

Intensive and Critical Care Nursing (2008) 24, 28—40 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Pathophysiology of acid base balance: The theory practice relationship Sharon L. Edwards ∗ Buckinghamshire Chilterns University College, Chalfont Campus, Newland Park, Gorelands Lane, Chalfont St. Giles, Buckinghamshire HP8 4AD, United Kingdom Accepted 13 May 2007 KEYWORDS Summary There are many disorders/diseases that lead to changes in acid base Acid base balance; balance. These conditions are not rare or uncommon in clinical practice, but every- Arterial blood gases; day occurrences on the ward or in critical care. Conditions such as asthma, chronic Acidosis; obstructive pulmonary disease (bronchitis or emphasaemia), diabetic ketoacidosis, Alkalosis renal disease or failure, any type of shock (sepsis, anaphylaxsis, neurogenic, cardio- genic, hypovolaemia), stress or anxiety which can lead to hyperventilation, and some drugs (sedatives, opoids) leading to reduced ventilation. In addition, some symptoms of disease can cause vomiting and diarrhoea, which effects acid base balance. It is imperative that critical care nurses are aware of changes that occur in relation to altered physiology, leading to an understanding of the changes in patients’ condition that are observed, and why the administration of some immediate therapies such as oxygen is imperative. © 2007 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Introduction the essential concepts of acid base physiology is necessary so that quick and correct diagnosis can The implications for practice with regards to be determined and appropriate treatment imple- acid base physiology are separated into respi- mented. ratory acidosis and alkalosis, metabolic acidosis The homeostatic imbalances of acid base are and alkalosis, observed in patients with differing examined as the body attempts to maintain pH bal- aetiologies. -

Severe Metabolic Acidosis in a Patient with an Extreme Hyperglycaemic Hyperosmolar State: How to Manage? Marloes B

Clinical Case Reports and Reviews Case Study ISSN: 2059-0393 Severe metabolic acidosis in a patient with an extreme hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state: how to manage? Marloes B. Haak, Susanne van Santen and Johannes G. van der Hoeven* Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands Abstract Hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state (HHS) and diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) are often accompanied by severe metabolic and electrolyte disorders. Analysis and treatment of these disorders can be challenging for clinicians. In this paper, we aimed to discuss the most important steps and pitfalls in analyzing and treating a case with extreme metabolic disarrangements as a consequence of an HHS. Electrolyte disturbances due to fluid shifts and water deficits may result in potentially dangerous hypernatriema and hyperosmolality. In addition, acid-base disorders often co-occur and several approaches have been advocated to assess the acid-base disorder by integration of the principles of mass balance and electroneutrality. Based on the case vignette, four explanatory methods are discussed: the traditional bicarbonate-centered method of Henderson-Hasselbalch, the strong ion model of Stewart, and its modifications ‘Stewart at the bedside’ by Magder and the simplified Fencl-Stewart approach. The four methods were compared and tested for their bedside usefulness. All approaches gave good insight in the metabolic disarrangements of the presented case. However, we found the traditional method of Henderson-Hasselbalch and ‘Stewart at the bedside’ by Magder most explanatory and practical to guide treatment of the electrolyte disturbances and in exploring the acid-base disorder of the presented case. Introduction This is accompanied by changes in pCO2 and bicarbonate (HCO₃ ) levels, depending on the cause of the acid-base disorder. -

Persistent Lactic Acidosis - Think Beyond Sepsis Emily Pallister1* and Thogulava Kannan2

ISSN: 2377-4630 Pallister and Kannan. Int J Anesthetic Anesthesiol 2019, 6:094 DOI: 10.23937/2377-4630/1410094 Volume 6 | Issue 3 International Journal of Open Access Anesthetics and Anesthesiology CASE REPORT Persistent Lactic Acidosis - Think beyond Sepsis Emily Pallister1* and Thogulava Kannan2 1 Check for ST5 Anaesthetics, University Hospitals of Coventry and Warwickshire, UK updates 2Consultant Anaesthetist, George Eliot Hospital, Nuneaton, UK *Corresponding author: Emily Pallister, ST5 Anaesthetics, University Hospitals of Coventry and Warwickshire, Coventry, UK Introduction • Differential diagnoses for hyperlactatemia beyond sepsis. A 79-year-old patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit for manage- • Remember to check ketones in patients taking ment of Acute Kidney Injury refractory to fluid resusci- Metformin who present with renal impairment. tation. She had felt unwell for three days with poor oral • Recovery can be protracted despite haemofiltration. intake. Admission bloods showed severe lactic acidosis and Acute Kidney Injury (AKI). • Suspect digoxin toxicity in patients on warfarin with acute kidney injury, who develop cardiac manifes- The patient was initially managed with fluid resus- tations. citation in A&E, but there was no improvement in her acid/base balance or AKI. The Intensive Care team were Case Description asked to review the patient and she was subsequently The patient presented to the Emergency Depart- admitted to ICU for planned haemofiltration. ment with a 3 day history of feeling unwell with poor This case presented multiple complex concurrent oral intake. On examination, her heart rate was 48 with issues. Despite haemofiltration, acidosis persisted for blood pressure 139/32. -

Evaluation and Treatment of Alkalosis in Children

Review Article 51 Evaluation and Treatment of Alkalosis in Children Matjaž Kopač1 1 Division of Pediatrics, Department of Nephrology, University Address for correspondence Matjaž Kopač, MD, DSc, Division of Medical Centre Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia Pediatrics, Department of Nephrology, University Medical Centre Ljubljana, Bohoričeva 20, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia J Pediatr Intensive Care 2019;8:51–56. (e-mail: [email protected]). Abstract Alkalosisisadisorderofacid–base balance defined by elevated pH of the arterial blood. Metabolic alkalosis is characterized by primary elevation of the serum bicarbonate. Due to several mechanisms, it is often associated with hypochloremia and hypokalemia and can only persist in the presence of factors causing and maintaining alkalosis. Keywords Respiratory alkalosis is a consequence of dysfunction of respiratory system’s control ► alkalosis center. There are no pathognomonic symptoms. History is important in the evaluation ► children of alkalosis and usually reveals the cause. It is important to evaluate volemia during ► chloride physical examination. Treatment must be causal and prognosis depends on a cause. Introduction hydrogen ion concentration and an alkalosis is a pathologic Alkalosis is a disorder of acid–base balance defined by process that causes a decrease in the hydrogen ion concentra- elevated pH of the arterial blood. According to the origin, it tion. Therefore, acidemia and alkalemia indicate the pH can be metabolic or respiratory. Metabolic alkalosis is char- abnormality while acidosis and alkalosis indicate the patho- acterized by primary elevation of the serum bicarbonate that logic process that is taking place.3 can result from several mechanisms. It is the most common Regulation of hydrogen ion balance is basically similar to form of acid–base balance disorders. -

Oral Rehydration of Adult Cattle Using Isotonic Solution of Sugar, Sodium Chloride and Potassium Chloride

Haryana Vet. (Dec., 2019) 58(2), 166-169 Research Article ABSTRACT Fig 2: Transmission electron photomicrograph of monocyte of dog Present study comprised of 72 crossbred cows (group I= 60 endometritic and group II=12 healthy) at 30±2days postpartum. The showing heterochromatin (a), euchromatin (b), cytoplasmic process (c), polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) cell coun Vacuole and nuclear membrane. Uranyl acetate and lead citrate × 25500 Figure 1: Cyclic conditions for PCR profiling for detection of Salmonella genes ASSOCIATION OF SEMEN TRAITS IN CONSECUTIVE EJACULATES WITH FSH-β GENE POLYMORPHISM IN HOLSTEIN-FRIESIAN CROSSBRED BULLS FROM INDIA VIJAY KADAM, ABH trus synchronizathod that synchronizes ovulations is Corresponding author: [email protected] Fig. 1. Histogram depicting frequency distribution of animal named briefly as “Ovsynch” (Pursley et al., 1995). The right score of respondents Clinical Article study was aimed to evaluate the efficacy of different methods of estrus sync Fig. 1. Semilogarithmic plot of plasma concentration time profile of amoxicillin and cloxacillin following single dose (10 mg/kg) i.v. and i.m. administration in sheep (n=4) Haryana Vet. (Dec., 2019) 58(2), 166-169 Research Article 2003) which might lead to increased chances of urolith the time for the urinary tract to restore patency (Parrah, Haryana Vet. (March, 2020) 59(SI), 93-95 Short Communication Research Article formation. The increased hospital incidence can also be 2009) in conjugation with supportive treatments like COMPARATIVE EFFICACY OF SYNCHRONIZATION PROTOCOLS FOR IMPROVING attributed to the proximity of the clinic as well. According to peritoneal lavage, urinary acidifiers and urinary ORAL REHYDRATION OF ADULT CATTLE USING ISOTONIC SOLUTION OF SUGAR, FERTILITY IN POSTPARTUM CROSSBRED DAIRY COWS data published by Department ff Soil Science, Haryana, antiseptics. -

Ethylene Glycol Ingestion Reviewer: Adam Pomerlau, MD Authors: Jeff Holmes, MD / Tammi Schaeffer, DO

Pediatric Ethylene Glycol Ingestion Reviewer: Adam Pomerlau, MD Authors: Jeff Holmes, MD / Tammi Schaeffer, DO Target Audience: Emergency Medicine Residents, Medical Students Primary Learning Objectives: 1. Recognize signs and symptoms of ethylene glycol toxicity 2. Order appropriate laboratory and radiology studies in ethylene glycol toxicity 3. Recognize and interpret blood gas, anion gap, and osmolal gap in setting of TA ingestion 4. Differentiate the symptoms and signs of ethylene glycol toxicity from those associated with other toxic alcohols e.g. ethanol, methanol, and isopropyl alcohol Secondary Learning Objectives: detailed technical/behavioral goals, didactic points 1. Perform a mental status evaluation of the altered patient 2. Formulate independent differential diagnosis in setting of leading information from RN 3. Describe the role of bicarbonate for severe acidosis Critical actions checklist: 1. Obtain appropriate diagnostics 2. Protect the patient’s airway 3. Start intravenous fluid resuscitation 4. Initiate serum alkalinization 5. Initiate alcohol dehydrogenase blockade 6. Consult Poison Center/Toxicology 7. Get Nephrology Consultation for hemodialysis Environment: 1. Room Set Up – ED acute care area a. Manikin Set Up – Mid or high fidelity simulator, simulated sweat if available b. Airway equipment, Sodium Bicarbonate, Nasogastric tube, Activated charcoal, IV fluid, norepinephrine, Simulated naloxone, Simulate RSI medications (etomidate, succinylcholine) 2. Distractors – ED noise For Examiner Only CASE SUMMARY SYNOPSIS OF HISTORY/ Scenario Background The setting is an urban emergency department. This is the case of a 2.5-year-old male toddler who presents to the ED with an accidental ingestion of ethylene glycol. The child was home as the father was watching him. The father was changing the oil on his car. -

Body Fluid Compartments Dr Sunita Mittal

Body fluid compartments Dr Sunita Mittal Learning Objectives To learn: ▪ Composition of body fluid compartments. ▪ Differences of various body fluid compartments. ▪Molarity, Equivalence,Osmolarity-Osmolality, Osmotic pressure and Tonicity of substances ▪ Effect of dehydration and overhydration on body fluids Why is this knowledge important? ▪To understand various changes in body fluid compartments, we should understand normal configuration of body fluids. Total Body Water (TBW) Water is 60% by body weight (42 L in an adult of 70 kg - a major part of body). Water content varies in different body organs & tissues, Distribution of TBW in various fluid compartments Total Body Water (TBW) Volume (60% bw) ________________________________________________________________ Intracellular Fluid Compartment Extracellular Fluid Compartment (40%) (20%) _______________________________________ Extra Vascular Comp Intra Vascular Comp (15%) (Plasma ) (05%) Electrolytes distribution in body fluid compartments Intracellular fluid comp.mEq/L Extracellular fluid comp.mEq/L Major Anions Major Cation Major Anions + HPO4- - Major Cation K Cl- Proteins - Na+ HCO3- A set ‘Terminology’ is required to understand change of volume &/or ionic conc of various body fluid compartments. Molarity Definition Example Equivalence Osmolarity Osmolarity is total no. of osmotically active solute particles (the particles which attract water to it) per 1 L of solvent - Osm/L. Example- Osmolarity and Osmolality? Osmolarity is total no. of osmotically active solute particles per 1 L of solvent - Osm/L Osmolality is total no. of osmotically active solute particles per 1 Kg of solvent - Osm/Kg Osmosis Tendency of water to move passively, across a semi-permeable membrane, separating two fluids of different osmolarity is referred to as ‘Osmosis’. Osmotic Pressure Osmotic pressure is the pressure, applied to stop the flow of solvent molecules from low osmolarity to a compartment of high osmolarity, separated through a semi-permeable membrane. -

Unit 4 Acid-Base Homeostasis

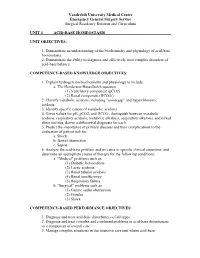

Vanderbilt University Medical Center Emergency General Surgery Service Surgical Residency Rotation and Curriculum UNIT 4 ACID-BASE HOMEOSTASIS UNIT OBJECTIVES: 1. Demonstrate an understanding of the biochemistry and physiology of acid-base homeostasis. 2. Demonstrate the ability to diagnose and effectively treat complex disorders of acid-base balance. COMPETENCY-BASED KNOWLEDGE OBJECTIVES: 1. Explain hydrogen ion biochemistry and physiology to include: a. The Henderson-Hasselbalch equation (1) Ventilatory component (pCO2) (2) Renal component (HCO3-) 2. Classify metabolic acidosis, including "anion gap" and hyperchloremic acidosis. 3. Identify specific causes of metabolic acidosis. 4. Given values for pH, pCO2, and HCO3-, distinguish between metabolic acidosis, respiratory acidosis, metabolic alkalosis, respiratory alkalosis, and mixed abnormalities; derive a differential diagnosis for each. 5. Predict the importance of primary diseases and their complications to the evaluation of patient risk for: a. Shock b. Bowel obstruction c. Sepsis 6. Analyze the acid-base problem and its cause in specific clinical situations, and determine an appropriate course of therapy for the following conditions: a. "Medical" problems such as: (1) Diabetic ketoacidosis (2) Lactic acidosis (3) Renal tubular acidosis (4) Renal insufficiency (5) Respiratory failure b. "Surgical" problems such as: (1) Gastric outlet obstruction (2) Fistulas (3) Shock COMPETENCY-BASED PERFORMANCE OBJECTIVES: 1. Diagnose and treat acid-base disturbances of all types. 2. Diagnose and treat complex and combined problems in acid-base disturbances as a component of overall care. 3. Manage complex situations in the intensive care unit where acid-base Vanderbilt University Medical Center Emergency General Surgery Service Surgical Residency Rotation and Curriculum abnormalities coexist with other metabolic derangements, including: a. -

Study on Acid-Base Balance Disorders and the Relationship

ArchiveNephro-Urol of Mon SID. 2020 May; 12(2):e103567. doi: 10.5812/numonthly.103567. Published online 2020 May 23. Research Article Study on Acid-Base Balance Disorders and the Relationship Between Its Parameters and Creatinine Clearance in Patients with Chronic Renal Failure Tran Pham Van 1, *, Thang Le Viet 2, Minh Hoang Thi 1, Lan Dam Thi Phuong 1, Hang Ho Thi 1, Binh Pham Thai 3, Giang Nguyen Thi Quynh 3, Diep Nong Van 4, Sang Vuong Dai 5 and Hop Vu Minh 1 1Biochemistry Department, Military Hospital 103, Hanoi, Vietnam 2Nephrology and Hemodialysis Department, Military Hospital 103, Hanoi, Vietnam 3National Hospital of Endocrinology, Hanoi, Vietnam 4Biochemistry Department, Backan Hospital, Vietnam 5Biochemistry Department, Thanh Nhan Hospital, Hanoi, Vietnam *Corresponding author: Biochemistry Department, Military Hospital 103, Hanoi, Vietnam. Email: [email protected] Received 2020 May 09; Accepted 2020 May 09. Abstract Objectives: We aimed to determine the parameters of acid-base balance in patients with chronic renal failure (CRF) and the rela- tionship between the parameters evaluating acid-base balance and creatinine clearance. Methods: The current cross-sectional study was conducted on 300 patients with CRF (180 males and 120 females). Clinical examina- tion and blood tests by taking an arterial blood sample for blood gas measurement as well as venous blood for biochemical tests to select study participants were performed. Results: Patients with CRF in the metabolic acidosis group accounted for 74%, other types of disorders were less common. The average pH, PCO2, HCO3, tCO2 and BE of the patient group were 7.35 ± 0.09, 34.28 ± 6.92 mmHg, 20.18 ± 6.06 mmol/L, 21.47 ± 6.48 mmHg and -4.72 ± 6.61 mmol/L respectively.