Hancock,Conni2015-09-17Transcript.Pdf (774.6Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Home with the Armadillo

Mellard: Home with the Armadillo Home with the Armadillo: Public Memory and Performance in the 1970s Austin Music Scene Jason Dean Mellard 8 Produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press, 2010 1 Greezy Wheels performing at the Armadillo World Headquarters. Photo courtesy of the South Austin Popular Culture Center. Journal of Texas Music History, Vol. 10 [2010], Iss. 1, Art. 3 “I wanna go home with the Armadillo Good country music from Amarillo and Abilene The friendliest people and the prettiest women You’ve ever seen.” These lyrics from Gary P. Nunn’s “London Homesick Blues” adorn the wall above the exit from the Austin Bergstrom International Airport baggage claim. For years, they also played as the theme to the award-winning PBS series Austin City Limits. In short, they have served in more than one instance as an advertisement for the city’s sense of self, the face that Austin, Texas, presents to visitors and national audiences. The quoted words refer, if obliquely, to a moment in 9 the 1970s when the city first began fashioning itself as a key American site of musical production, one invested with a combination of talent and tradition and tolerance that would make of it the self-proclaimed “Live Music Capital of the World.”1 In many ways, the venue of the Armadillo World Headquarters served as ground zero for these developments, and it is often remembered as a primary site for the decade’s supposed melding of Anglo-Texan traditions and countercultural lifestyles.2 This strand of public memory reveres the Armadillo as a place in which -

Music City Texas

# 8 9 JANUARY 1997 TOWNES IMN ZANDT The days up and down (hey come Like rain on a conga drum Forgetting most, remember some But don't turn none away Everything is not enough Nothing is too much to bear Where you've been is good and gone All you keep’s the getting there To live s to fly. lou; and high So shake the dust off of your wings And the sleep out of your eyes He changed my life MCT1996 POLL HONEST JOHN REVIEWS Russ Bartlett • Ray Campi v Professor Longhair • Michele Murphy j KEN SCHAFFER’S A EGGE • KIM MILLER • LINDA LOZANO SAFETY IN NUMBERS SHOWCASE at its new home in the highly acclaimed LA PALAPA Restaurant and Cantina 6640 HWY 290 EAST (east of Highland Mall) at 6:00PM, NO COVER ' ’+ o o * i > o ° <0 ¿F Í , í J . u N .»O' « a i Ken lays out the welcome mat to all comers TOGETHER seeking the quintessential Austin music moment, Sat, Jan 11th, Belton Acoustic Concert Series, 7pm (details 817/778-5440) because he”H bet they can find it here. Fri, Jan 24th, Waterloo Ice House, 6th & Lamar, 9pm Call 419-1781 for sign up and details Egge: Thu, Jan 30th, Artz Rib House, 7pm Miller: Rouse House Concert, with L J Booth, u THE BEST OF THE UP AND COMING’’ April 26th (837-2333) < J / l N U A R y n V oVonW r i / aUer'i' VÜRE f X W s B s n d Mondays at gabe's, 9pm V Tuesdays at *Jovita's, 8pm Saturday 4th, groken Spoke, 9pm Saturday 18th, Mucky Duck, Houston, 8pm <£ 10.30pm RETR9VOGU6 Jriday 24th, Cactus Cafe, 9pm, & RELICS with special guest Staid Cleaves 2024 South Lamar Boulevard • Phone No 442-4446 &K9Mg9Mg you t h e /j e s t 9 m eouM^ny m u s 9C 'EÜKSÍlH ^tryiIIiñJKS— i KUT MAKES MUSIC! 5 5 3 5 BURNET RD. -

Bob Wills: the King of Western Swing Contributors Gary Hartman Rush Evans Rush Evans

et al.: Contents Letter from the Director The beginning of the Fall Wylie Hubbard, have been very successful. Our third CD, which 2002 semester marks the will feature Jerry Jeff Walker, Rosie Flores, The Flatlanders, and third year since the Center others, will be available soon. Proceeds from the CDs have been for Texas Music History vital in helping fund our ongoing educational projects. We are very (formerly the Institute for grateful to the musicians and everyone else who contributed. the History of Texas Music) We are very pleased to be working closely with the Bob Bul- was officially established in lock Texas State History Museum, the Country Music Hall of the History Department at Fame and Museum, and others to help present the “Country Southwest Texas State Music from the Lone Star State” exhibit, which will run through University. During those January 2003. This issue of the Journal of Texas Music History three years, the CTMH has features an in-depth article about the exhibit. I strongly en- compiled an impressive list courage all our readers to visit the Bullock Museum to experi- of accomplishments. ence this wonderful presentation on Texas music history. With the help and I am very grateful to the following people for their hard work support of many good people and businesses throughout the and generous support: Kathryn Ledbetter, Gregg Andrews, Vikki Southwest, we have built a unique and important program Bynum, Jenni Finlay, Dawn Shepler, Ann Marie Ellis, Gene focusing on the preservation and study of the region’s complex Bourgeois, the entire SWT History Department, the CTMH and diverse musical heritage. -

BETWEEN the PAGES a Publication of the Friends of the Allen Public Library

BETWEEN THE PAGES A Publication of the Friends of the Allen Public Library July/August 2012 www.allenfriends.org Volume IX, Issue IV FOL Board Upcoming Events at the Library (all free, of course) President - Susan Jackson VP/Community Relations Tuesday, July 3 at 7:00 p.m. "Muppet Treasure Island” Dana Jean Wednesday, July 4 all day Library Closed Secretary - Julie Hlad Friday, August 24 all day Library Closed Treasurer – Tami Alexander Tuesday, July 10 at 7:00 p.m. "An American Tail" Communications Friday, July 13 at 7:30 p.m. Dallas Banjo Band Tom Keener Tuesday, July 17 at 7:00 p.m. "The Great Muppet Caper" Ongoing Book Sale Thursday, July 19 at 7:30 p.m. What Ever Happened to Heroes? Brenda Kiser Tuesday, July 24 at 7:00 p.m. “Stuart Little” Membership Tuesday, July 31 at 7:00 p.m. Armchair Traveler to England Tami Burich Thursday, August 9 at 7:30 p.m. Ponty Bone and the Squeezetones Supply Mgr./Historian Sandy Wittsche Friday, August 17 at 7:30 p.m. Shoot Low Sheriff Arts Alliance Liaison Regina Taylor PLUS, don’t forget Tuesday Nights at the Movies in August. Volunteer Coordinator open And stay tuned for even more activities at the library—see www.allenfriends.org and ALLen Reads www.allenlibrary.org, or check out our Facebook page! Jane Bennett Junior Friends Leader Vandana Bains Newsletter - Bonnie Jay Hello, Friends Members, Bach to Books—open I wanted to take this opportunity to introduce myself. I am Susan Jackson, your recently Endowment Bd. -

John Fullbright Pg 30 “What’S So Bad About Happy?” T He Oklahoma Tunesmith Seeks Answers to That Burning Question and Others While Crafting the Songs of His Life

LoneStarMusic | 1 2 | LoneStarMusic LoneStarMusic | 3 inside this issue JOHN FULLBRIGHT pg 30 “What’s so bad about happy?” T he Oklahoma tunesmith seeks answers to that burning question and others while crafting the songs of his life. by Lynne Margolis FEATUREs 26 Q&A: Billy Joe Shaver — By Holly Gleason 38 Miranda Lambert: The true heart and real deal behind the platinum supernova — By Holly Gleason 42 The Mastersons: The duke and duchess of Americana power pop embrace their chemistry on Good Luck Charm — By Holly Gleason 43 Corb Lund: Americana’s favorite Hurtin’ Albertan goes to Memphis — By Adam Dawson 46 Kelly Willis and Bruce Robison: “This will be our year, took a long time to come ...” — By Richard Skanse 50 Robyn Ludwick: Hard woman with a heartache — By Richard Skanse John Fullbright photo by John Carrico 4 | LoneStarMusic LoneStarMusic | 5 after awhile inside this issue Publisher: Zach Jennings Editor: Richard Skanse Notes from the Editor | By Richard Skanse Creative Director/Layout: Melissa Webb Cover Photo: John Carrico I can’t, for the life of me, remember what song it was that John Fullbright Advertising/Marketing: Kristen Townsend played the first time I saw him — but I damn sure remember the impact. Advertising: Erica Brown It was back in February 2011 at the 23rd International Folk Alliance Conference Artist & Label Relations: Kristen Townsend in Memphis, sometime well after midnight, when the private showcases overrunning the top three floors of the Marriott were in full swing. I’d wandered Contributing Contributing from room to room for what felt like (and probably was) hours, catching a song Writers Photographers here, a short set there, and foraging for drinks and late-night snacks the whole time. -

HONEST JOHN • Births & Deaths

rH coast MUSIC Formerly MUSIC CITY TEXAS ' BRADLEY JAYE #1/90 FEBRUARY WILLIAMS The Gulf Coast Playboys HONEST JOHN • Births & Deaths REVIEWS Johnnie Allan • Ray Campi Rosie & Flores 'Rockabilly Music & Its Makers' • Aldus Roger Eddie 'Lalo'Torres • World Accordion Anthology Townes Van Zandt LARGE SELECTION OF VINTAGE CLOTHING i THE LAST c o MUSIC CITY TEXAS m n MUSIC AWARDS ! UNDERTHESUN O POLL PARTY A Vintage Emporium tu n Champ Hood & The Threadgill's Troubadors < H Jimmie Dale Gilmore • Ray Wylie Hubbard Asylum Street Spankers • Los Pinkys > Christina Marrs & The Jubilettes c8 Don Walser • Scott Walls • Jesse Taylor 5341 BURNET RD 73 nm Gary Prlmich • Rod Moag • Ponty Bone > AUSTIN, O Kevin Smith • Randy Glines LLi 73 TEXAS 78756 K3 Ana Egge, Linda Lozano & Kim Miller (512) 453-8128 in and special guests LU 8? Steue Clark • Larry Monroe • Griff Luneberg l/"l 5 d6 c >- V/Ì MONDAY =) r\ February 17th CQ 5 O m THREADGILL'S i/i 2 WORLD HEADQUARTERS _i o < 7 3 Barton Springs & Riverside LU > 6.30-J0pm, no cover —flm.Lt.Lc.d.n. &a"ad. Sa-u.tfLt.tn. S ty le £ GJ Dedicated to the memory of Martha Taylor Fain 4 0 S- 7 O S HOUSEWARES, FURNITURE 8c KITSCH > % Vcm/Wedw'y jevnuAKy Mondays at gate's, 9pm Tuesdays at Jovita’s, 8pm (except 4th) Saturday 1st, groken Spoke, 9pm Jriday 21st, glanco's, Houston RETR9VOGUC Saturday 22nd, Jlag Hall, gurlington, nearetemple & RELICS Thursday 29th, Jrench Cegation, 9.30am 2024 South Lamar Boulevard • Phone No 442-4446 gR9MÇ9MÇ yOU THE g EST 9JO GOlAJOTRy JVIUS9C jUITÄKS KUT MAKES MUSIC! 5 5 3 5 BURHET RD. -

P. 001-003 Front Matter

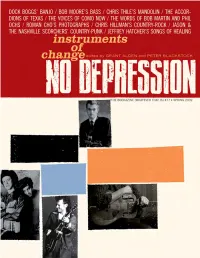

slate ○○○○○○○○○ DOCK BOGGS’ BANJO ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 4 by Jesse Fox Mayshark ○○○○○○○○○○ THE VOICES OF COMO NOW ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 14 by David Menconi ○○○○○○○○○○○○ THE ACCORDIONS OF TEXAS ○○○○○○○○○○○ 20 by Joe Nick Patoski ○○○○○○○○○ BOB MOORE’S BASS ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 36 by Rich Kienzle ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ THE WORDS OF BOB MARTIN ○○○○○ 48 by Bill Friskics-Warren ROMAN CHO’S PHOTOGRAPHS ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○54 live, from McCabe’s Guitar Shop ○○○○○○○ CHRIS THILE’S MANDOLIN ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 68 by Seth Mnookin ○○○○○○○○○○○ CHRIS HILLMAN’S COUNTRY-ROCK ○○○○○○○○○ 84 by Barry Mazor ○○○○○ JASON & THE NASHVILLE SCORCHERS’ COUNTRY-PUNK ○○○○○○○ 96 by Don McLeese ○○○○○○○ JEFFREY HATCHER’S SONGS OF HEALING ○○○○○○○○○○○ 110 by Lloyd Sachs ○○○○○○○○ THE WORDS OF PHIL OCHS ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 128 by Kenneth J. Bernstein ○○○○○○○○ APPENDIX: REVIEWS ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 136 Buddy & Julie Miller; Neko Case; Madeleine Peyroux; David Byrne & Brian Eno; Bruce Robison; A Tribute to Doug Sahm. COVER DESIGN BY JESSE MARINOFF REYES in homage to Reid Miles, repurposing photographs by Paul Cantin, John Carrico, Roman Cho, along with several uncredited promotional images INTERIOR PAGES DESIGNED BY GRANT ALDEN Copyright © 2009 by No Depression All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First edition, 2009 Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to: Permissions University of Texas Press P.O. Box 7819 Austin, TX 78713-7819 www.utexas.edu/utpress/about/bpermission.html The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) (Permanence of Paper). ISBN 978-0-292-71929-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2008931429 This volume has been printed from camera-ready copy furnished by the author, who assumes full responsibility for its contents. the bookazine (whatever that is) #77 • spring 2009 Back when we were a bimonthly magazine, articles mostly were assigned around the release date of record albums. -

Texas Music Office (512)

Missouri – Mobile Recording 151 Missouri City Civic Center Amy E. Mitchell Mixture 1522 Texas Parkway, Missouri City, TX 77489 4607 Clawson Road, Austin, TX 78745 (281) 261-4290; [email protected] Attorney & Counselor at Law (512) 462-2611 Jennifer Sooy P.O. Box 49547 [email protected] Austin, TX 78765 Mark Younger-Smith, Owner/Producer Mr. A’s (512) 970-7824; (866) 514-3973 3409 Cavalcade, Houston, TX 77026 [email protected] Mlar Records (713) 675-2319 http://www.amyemitchell.com 10110 West Sam Houston South Parkway, Suite 150 Tony Attorneys • Music business consultants Houston, TX 77099-5109 Austin Music Foundation (832) 351-3511 Mr. Cassette of Texas Entertainment Law Section of the State Bar of Texas Po White 4930 Burnet Road, Suite 100, Austin, TX 78756-2600 Austin Young Lawyers Association (512) 452-5050; Fax (512) 452-6441 American Bar Association Mo’ Ranch [email protected] Established: 2004 P.O. Box 870, Blanco, TX 78606 Carol Humphrey, Sole Proprietor Amy E. Mitchell, a sole practitioner based in Aus- (830) 833-5430 tin, practices entertainment law with a focus on emerg- Waymond Lightfoot Mr. E’s Electronics ing bands. Work experience includes reviewing indie 2818 Hillcrest Drive, San Antonio, TX 78201-7046 label deals, production agreements, and label shop- Mo’s Place (210) 737-6737 ping agreements, as well as drafting, structuring, and 21940 Kingsland, Katy, TX 77450 negotiating music industry deals. She graduated from (281) 392-3499 the University of Texas School of Law in 2004 and is Mr. E’s licensed to practice law in Texas. -

463-6666 [email protected] Martin, Dale

Martin, Dale – Matthews, Sherry 151 Dale Martin, Music Writer Mas Distributors • Houston Masterpiece Mastering P.O. Box 311200, New Braunfels, TX 78131 819 Hogan, Houston, TX 77009 P.O. Box 2130 (830) 626-3424; Fax (830) 626-0825 (713) 228-7773 Wimberley, TX 78676-2130 [email protected] Matias Ramirez, Owner (512) 842-1431; Fax (512) 842-1431 [email protected] Michael Martin Mason Country Opry at the Odeon Theater www.masterpiecemastering.com P.O. Box 10662, Austin, TX 78766-1662 1701 South Bridge Street, Brady, TX 76825-7031 Billy Stull (512) 454-1135; (512) 462-2219; Fax (512) 454-5483 (325) 597-1895; (325) 597-2119; Fax (325) 597-0515 Mastering • Audio engineers [email protected] Compact disc manufacturers • Record producers Martin Professional, Inc. Tracy Pitcox, Producer National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences 7120 Rufe Snow Drive, Bldg. 106, Suite 303 Established: 1997 North Richland Hills, TX 76148 Mason Studio Established in beautiful Wimberley TX in 1997, the (817) 577-8404; (800) 200-1210; Fax (817) 577-8604 216 Forest Drive, Lake Jackson, TX 77566 tuned mastering laboratory now features an incredible Jeff Dougherty, Regional Sales Manager (979) 297-8924; [email protected] custom Analog Mastering System designed by Rodney Mason, Owner legendary audio designer Rupert Neve and conceived Narciso Martinez Cultural by veteran mastering engineer Billy Stull. This System Masquerade Entertainment dubbed Masterpiece is produced and marketed Arts Center 2186 Jackson Keller, Suite 412, San Antonio, TX 78213 worldwide by Legendary Audio P.O. Box 471 (210) 377-3535; Fax (210) 342-2568 www.legendaryaudio.com. Masterpiece empowers the San Benito, TX 78586 Ernest Calderon, Coordinator audio engineer to enhance, restructure, or repair stereo (956) 361-0110; (956) 425-9552; Fax (956) 361-0767 audio masters-digital or analog. -

Counterculture Cowboys: Progressive Texas Country of the 1970S & 1980S

Lock: Counterculture Cowboys Counterculture Cowboys: Counterculture Progressive Texas Country of the 1970s & 1980s Texas Progressive CountercultureCounterculture Cowboys:Cowboys: ProgressiveProgressive TexasTexas CountryCountry ofof thethe 1970s1970s && 1980s1980s CoryCory Lock 14 Country music undeniably forms a vital and prominent part of Texas culture. Texas country musicians have long been innovators, not only fashioning a distinctive brand of regional music, but also consistently enriching the music and general culture of the American nation as a whole. Artists such as Bob Wills, Gene Autry, Ernest Tubb, Ray Price, Willie Nelson, George Strait, and the Dixie Chicks have become national icons and have helped shape mainstream American perceptions of what it is to be “country.” WProducedillie Nelson. by November The Berkeley 4, 1972. Electronic Photo by Press, Burton 2003 Wilson 1 Journal of Texas Music History, Vol. 3 [2003], Iss. 1, Art. 3 Counterculture Cowboys: Counterculture Progressive Texas Country of the 1970s & 1980s Texas Progressive Yet while the import of country music within regional and The trend to which I refer began in the early 1970s and national culture is certain, people are much less decided on what continued through the mid-1980s. In his Country Music USA country music means. What is it that makes country country? chapter, “Country Music, 1972-1984,” Bill Malone approaches What does the music as a whole stand for? Is it a nostalgic genre this time period as a coherent unit in which country music and that hearkens us back to the good old days of yesteryear? Many culture drew the attention of the nation as a whole. Country people believe so, emphasizing country music’s role in preserving entertainers graced the covers of national news magazines, such what is most traditional in American culture. -

Jesse "Guitar" Taylor

Jesse "Guitar" Taylor Best remembered as the ferocious lead guitarist behind country maverick Joe Ely, Jesse"Guitar" Taylor was born in Lubbock, Texas, in 1950. Raised by his mother, his friends growing up included a who's who of West Texas Talent: Joe Ely, Jimmie Dale Gilmore, Butch Hancock, John X. Reed, Ponty Bone, Lloyd Maines, T.J. McFarland, Jo Carol Pierce and Terry Allen, to name a few. Inspired by local boy made good Buddy Holly, Taylor began playing guitar as an adolescent, and by age 15 was serving in Jimmie Dale Gilmore's first group, the T. Nickel House Band. In 1967 Taylor joined Angela Strehli's band, playing shows on Austin's East Side. A former Golden Gloves boxer, Jesse Taylor was the first white musician to play at the original Stubb's BBQ in Lubbock, starting a series of Sunday jam sessions that prompted Stevie Ray Vaughan to drive up from Austin to sit in. Taylor joined Ely in time for the singer/songwriter's self-titled 1977 debut LP, a cult classic bettered by its follow-up, Honky Tonk Masquerade. While commercial country radio wanted nothing to do with these albums, Ely won much acclaim from rock and roll audiences and critics, and while touring the U.K. in support of Merle Haggard, he and Taylor befriended the legendary punk band The Clash, whom they supported on the road in 1979. Taylor's visceral, live wire guitar work made an enormous impression on The Clash's punk audience, and a London gig later formed the basis of the 1980 concert LP Live Shots. -

Elvis Presley in Texas–1955 Elvis Presley in Texas–1955

et al.: Contents Letter from the Director As this Spring 2003 issue of very successful fundraiser for our ongoing educational projects. the Journal of Texas Music Our sincerest thanks to these musicians and everyone else for History goes to press, the helping support our efforts. Center for Texas Music Finally, I am profoundly grateful to the following people who History (formerly the have worked very hard to make our program so successful: Institute for the History of Kathryn Ledbetter, Gregg Andrews, Dawn Shepler, Dee Lannon, Texas Music) continues to Beverly Braud, Ann Marie Ellis, Gene Bourgeois, Vikki Bynum, develop important new the entire SWT History Department, the CTMH Board of programs and activities Advisors, Becky Huff, Gerald Hill, T.Cay Rowe, Diana Harrell, focusing on the preservation César Limón, Francine Hartman, Rick and Laurie Baish, Lucky and study of the Southwest’s and Becky Tomblin, Kim and Robert Richey, Jo and Paul Snider, complex and diverse musical Margie First, Darrell and Barbara Piersol, Tracie Ferguson, Phil heritage. and Cecilia Collins, Ralph and Patti Dowling, Jerry and Cathy Our graduate and Supple, Dennis and Margaret Dunn, John Kunz, Kent Finlay, undergraduate courses on the history of Southwestern music Billy Seidel, and all of our other friends who have contributed continue to be very popular. The Handbook of Texas Music, which to the success of the Center for Texas Music History. we are co-publishing with the Texas State Historical Association, Please contact us for more information or to become involved the Texas Music Office, and the University of Texas at Austin, in this unique and exciting program.