The Industrial Revolution / Manchester

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

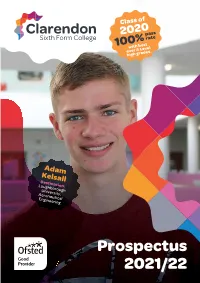

Prospectus 2021/22

Lewis Kelsall 2020 Destination:e Cambridg 100 with bestLeve l University, ever A . Engineering high grades Adam Kelsall Destination: Loughborough University Aeronautical, Engineering Clarendon Sixth Form College Camp Street Ashton-under-Lyne OL6 6DF Prospectus 2021/22 03 Message from the Principal 04 Choose a ‘Good’ College 05 Results day success 06 What courses are on offer? 07 Choosing your level and entry requirements 08 How to apply 09 Study programme 12 Study skills and independent learning programme 13 Extended Project Qualification (EPQ) and Futures Programme 14 Student Hub 16 Dates for your diary 17 Travel and transport 18 University courses at Tameside College 19 A year in the life of... Course Areas 22 Creative Industries 32 Business 36 Computing 40 English and Languages 44 Humanities 50 Science, Mathematics and Engineering 58 Social Sciences 64 Performing Arts 71 Sports Studies and Public Services 02 Clarendon Sixth Form College Prospectus 2021/22 Welcome from the Principal Welcome to Clarendon Sixth Form College. As a top performing college in The academic and support Greater Manchester for school leavers, package to help students achieve while we aim very high for our students. Our studying is exceptional. It is personalised students have outstanding success to your needs and you will have access to a rates in Greater Manchester, with a range of first class support services at each 100% pass rate. stage of your learning journey. As a student, your career aspirations and This support package enables our students your college experience are very important to operate successfully in the future stages of to us. -

Greater Manchester, New Hampshire

Greater Manchester, New Hampshire Health Improvement Plan 2016 with support from the City of Manchester Health Department and the Greater Manchester Public Health Network WORKING TO IMPROVE THE HEALTH AND WELL-BEING OF THE GREATER MANCHESTER REGION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The City of Manchester Health Department and the Greater Manchester Public Health Network are pleased to present the first Health Improvement Plan for the Greater Manchester Public Health Region. Our collective vision is to transform public health in our region to an integrated system capable of seamless collaborations among all healthcare providers and public safety personnel with constructive engagement of patients, families, and communities. Through this integrated system, all people will have equitable access to timely, comprehensive, cost-effective, high-quality, and compassionate care. Public health is the practice of preventing disease and promoting good health within groups of people-- from small communities to entire countries. Public Health is YOUR health. It embodies everything from clean air to safe food and water, access to healthcare and safer communities. Through public health planning and prevention initiatives, the public gets sick less frequently, children grow to become healthy adults through adequate resources including health care, and our community reduces the impact of disasters by preparing people for the effects of catastrophes such as hurricanes, floods and terrorism. In preparing this Plan, the Public Health Network and its workgroups have reviewed needs assessments, utilizing data from many different sources such as community focus groups, key stakeholder interviews, and surveys. Building on this information, needs have been prioritized and work plans have been developed. This Health Improvement Plan identifies needs, goals, measurable objectives, and strategies to help us as we work together on solutions to important issues facing our community. -

Diary of William Owen from November 10, 1824 to April 20, 1825 Ed. by Joel W

Library of Congress Diary of William Owen from November 10, 1824 to April 20, 1825 ed. by Joel W. Hiatt. INDIANA HISTORICAL SOCIETY PUBLICATIONS. VOLUME IV. NUMBER 1. DIARY OF WILLIAM OWEN From November 10, 1824, to April 20, 1825 EDITED BY JOEL W. HIATT LC INDIANAPOLIS: THE BOBBS-MERRILL COMPANY. 1906. 601 25 Pat 14 F521 .I41 114026 08 iii PREFACE. 3 456 Part 2 8 The manuscript of this diary of William Owen has remained in the hands of his only daughter—formerly Mary Francis Owen, now Mrs. Joel W. Hiatt—for many years and its existence, save to a few, has been unknown. It is fragmentary in form. It is possibly the close of a journal which had been kept for years before. Its first sentence in the original is an incomplete one, showing that there was an antecedent portion. The picture of the times is so graphic than the Indiana Historical Society publishes it, on account of its historical value. Mr. Owen was 22 years old at the time of its composition. Diary of William Owen from November 10, 1824 to April 20, 1825 ed. by Joel W. Hiatt. http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbtn.14024 Library of Congress William Owen was the second of four sons born to Robert and Ann Caroline Owen, of Scotland. Their names were Robert Dale, William, David Dale, and Richard. Three of them, Robert Dale, David Dale and Richard are known where ever the sun shines on the world of literature or science. William, who, because of habit or for his own amusement, wrote this diary is not known to fame. -

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES PATH DEPENDENCE and the ORIGINS of COTTON TEXTILE MANUFACTURING in NEW ENGLAND Joshua L. Rosenbloom Wo

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES PATH DEPENDENCE AND THE ORIGINS OF COTTON TEXTILE MANUFACTURING IN NEW ENGLAND Joshua L. Rosenbloom Working Paper 9182 http://www.nber.org/papers/w9182 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 September 2002 I thank Gavin Wright for his comments on an earlier version of this paper and Peter Temin and Doug Irwin for making available to me their data on cotton textile production and tariffs. The views expressed herein are those of the author and not necessarily those of the National Bureau of Economic Research. © 2002 by Joshua L. Rosenbloom. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Path Dependence and the Origins of Cotton Textile Manufacturing in New England Joshua L. Rosenbloom NBER Working Paper No. 9182 September 2002 JEL No. N6, N4 ABSTRACT During the first half of the nineteenth century the United States emerged as a major producer of cotton textiles. This paper argues that the expansion of domestic textile production is best understood as a path-dependent process that was initiated by the protection provided by the Embargo Act of 1807 and the War of 1812. This initial period of protection ended abruptly in 1815 with the conclusion of the war and the resumption of British imports, but the political climate had been irreversibly changed by the temporary expansion of the industry. -

Spinning and Winding Taro Nishimura

The_Textile_Machinery_Society_of_Japan_Textile_College_2-Day_Course_on_Cloth_Making_Introduction_to_Spinning_2014_05_22 Spinning and Winding Taro Nishimura 1. Introduction Since several thousand years ago, humans have been manufacturing linen, wool, cotton, and silk to be used as fibrous materials for clothing. In 繊維 (sen’i ), which is the word for “fiber,” the Chinese character 繊 (sen ) is a unit for decimal fractions of one ten-millionth (equal to approximately 30 Ǻ), while 維 (i) means “long and thin.” Usually, fibers are several dozen µ thick, and can range from around one centimeter long to nigh infinite length. All natural materials, with the exception of raw silk, are between several to several dozen centimeters long and are categorized as staple fibers. Most synthetic fibers are spun into filaments. Figure 1 shows how a variety of textile product forms are interrelated. Short fibers are spun into cotton (spun) yarns, whereas filaments are used just as they are, or as textured yarns by being twisted or stretched. Fabric cloths that are processed into two-dimensional forms using cotton (spun) yarns and filament yarns include woven fabrics, knit fabrics, nets, and laces. Non-woven fabrics are another type of two-dimensional form, in which staple fibers and filaments are directly processed into cloths without being twisted into yarns. Yet another two-dimensional form is that of films, which are not fiber products and are made from synthetic materials. Three-dimensional fabrics and braids are categorized as three-dimensional forms. This paper discusses spinning, or the process of making staple fibers into yarns, and winding, which prepares fibers for weaving. One-dimensional Two-dimensional Three-dimensional Natural Staple fibers Spun yarns Woven fabrics Three-dimensional materials Filaments Filament yarns Knit fabrics fabrics Synthetic Nets Braids materials Laces Non-woven fabrics Films Fig. -

The Factory, Manchester

THE FACTORY, MANCHESTER The Factory is where the art of the future will be made. Designed by leading international architectural practice OMA, The Factory will combine digital capability, hyper-flexibility and wide open space, encouraging artists to collaborate in new ways, and imagine the previously unimagined. It will be a new kind of large-scale venue that combines the extraordinary creative vision of Manchester International Festival (MIF) with the partnerships, production capacity and technical sophistication to present innovative contemporary work year-round as a genuine cultural counterweight to London. It is scheduled to open in the second half of 2019. The Factory will be a building capable of making and presenting the widest range of art forms and culture plus a rich variety of technologies: film, TV, media, VR, live relays, and the connections between all of these – all under one roof. With a total floor space in excess of 15,000 square meters, high-spec tech throughout, and very flexible seating options, The Factory will be a space large enough and adaptable enough to allow more than one new work of significant scale to be shown and/or created at the same time, accommodating combined audiences of up to 7000. It will be able to operate as an 1800 seat theatre space as well as a 5,000 capacity warehouse for immersive, flexible use - with the option for these elements to be used together, or separately, with advanced acoustic separation. It will be a laboratory as much as a showcase, a training ground as well as a destination. Artists and companies from across the globe, as well as from Manchester, will see it as the place where they can explore and realise dream projects that might never come to fruition elsewhere. -

Mental Strain As Field of Action in the 4Th Industrial Revolution

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia CIRP 17 ( 2014 ) 100 – 105 Variety Management in Manufacturing. Proceedings of the 47th CIRP Conference on Manufacturing Systems Mental strain as field of action in the 4th industrial revolution Uwe DOMBROWSKI, Tobias WAGNER* Institute for Advanced Industrial Management (IFU), Technische Universität Braunschweig, Langer Kamp 19, 38106 Braunschweig * Corresponding author. Tel.: "+49 531 391-2725" ; Fax: +49 531 391-8237. E-mail address: [email protected] Abstract Industrial revolutions have changed the society by a development of key-technologies. The vision of the 4th industrial revolution is triggered by technological concepts and solutions to realize a combination of the economy of scale with the economy of scope. This aim is also known as mass customization and is characterized by handling a high level of complexity with a total network integration of products and production processes. These technology-driven changes also lead to new fields of activity in the industrial science and the occupational psychology. The 4th industrial revolution intends to implement the collaboration between humans and machines. At the same time, processes are locally controlled and planned. For humans, this results to new work items. Resulting psychological effects should be investigated. This paper classifies the 4th industrial revolution systematically and describes future changes for employees. It derives the necessity of labor- psychological analysis of new key technologies like cyber physical systems. A theoretical foundation of a psychological work requirement analysis by using the VERA method is given. -

Technology, Labor, and Mechanized Bodies in Victorian Culture

Syracuse University SURFACE English - Dissertations College of Arts and Sciences 12-2012 The Body Machinic: Technology, Labor, and Mechanized Bodies in Victorian Culture Jessica Kuskey Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/eng_etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Kuskey, Jessica, "The Body Machinic: Technology, Labor, and Mechanized Bodies in Victorian Culture" (2012). English - Dissertations. 62. https://surface.syr.edu/eng_etd/62 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in English - Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT While recent scholarship focuses on the fluidity or dissolution of the boundary between body and machine, “The Body Machinic” historicizes the emergence of the categories of “human” and “mechanical” labor. Beginning with nineteenth-century debates about the mechanized labor process, these categories became defined in opposition to each other, providing the ideological foundation for a dichotomy that continues to structure thinking about our relation to technology. These perspectives are polarized into technophobic fears of dehumanization and machines “taking over,” or technological determinist celebrations of new technologies as improvements to human life, offering the tempting promise of maximizing human efficiency. “The Body Machinic” argues that both sides to this dichotomy function to mask the ways the apparent body-machine relation is always the product of human social relations that become embedded in the technologies of the labor process. Chapter 1 identifies the emergence of this dichotomy in the 1830s “Factory Question” debates: while critics of the factory system described workers as tools appended to monstrous, living machines, apologists claimed large-scale industrial machinery relieved human toil by replicating the laboring body in structure and function. -

Leading Artists Commissioned for Manchester International Festival

Press Release LEADING ARTISTS COMMISSIONED FOR MANCHESTER INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL High-res images are available to download via: https://press.mif.co.uk/ New commissions by Forensic Architecture, Laure Prouvost, Deborah Warner, Hans Ulrich Obrist with Lemn Sissay, Ibrahim Mahama, Kemang Wa Lehulere, Rashid Rana, Cephas Williams, Marta Minujín and Christine Sun Kim were announced today as part of the programme for Manchester International Festival 2021. MIF21 returns from 1-18 July with a programme of original new work by artists from all over the world. Events will take place safely in indoor and outdoor locations across Greater Manchester, including the first ever work on the construction site of The Factory, the world-class arts space that will be MIF’s future home. A rich online offer will provide a window into the Festival wherever audiences are, including livestreams and work created especially for the digital realm. Highlights of the programme include: a major exhibition to mark the 10th anniversary of Forensic Architecture; a new collaboration between Hans Ulrich Obrist and Lemn Sissay exploring the poet as artist and the artist as poet; Cephas Williams’ Portrait of Black Britain; Deborah Warner’s sound and light installation Arcadia allows the first access to The Factory site; and a new commission by Laure Prouvost for the redeveloped Manchester Jewish Museum site. Manchester International Festival Artistic Director & Chief Executive, John McGrath says: “MIF has always been a Festival like no other – with almost all the work being created especially for us in the months and years leading up to each Festival edition. But who would have guessed two years ago what a changed world the artists making work for our 2021 Festival would be working in?” “I am delighted to be revealing the projects that we will be presenting from 1-18 July this year – a truly international programme of work made in the heat of the past year and a vibrant response to our times. -

BRAZIL MILL, KNOTT MILL, MANCHESTER, Greater Manchester

BRAZIL MILL, KNOTT MILL, MANCHESTER, Greater Manchester Archaeological Watching Brief Oxford Archaeology North February 2007 Castlefield Estates Issue No: 2006-07/643 OA North Job No: L9798 NGR: centred SJ 383381 397472 Document Title: BRAZIL MILL, KNOTT MILL, MANCHESTER Document Type: Archaeological Watching Brief Client Name: Castlefield Estates Issue Number: 2006-07/643 OA Job Number: L9798 National Grid Reference: SJ 383381 397472 Prepared by: Ian Miller Signed……………………. Position: Project Manager Date: March 2005 Approved by: Alan Lupton Signed……………………. Position: Operations Manager Date: February 2007 Document File Location Wilm/Projects/L9798/Report Oxford Archaeology North © Oxford Archaeological Unit Ltd 2007 Storey Institute Janus House Meeting House Lane Osney Mead Lancaster Oxford LA1 1TF OX2 0EA t: (0044) 01524 848666 t: (0044) 01865 263800 f: (0044) 01524 848606 f: (0044) 01865 793496 w: www.oxfordarch.co.uk e: [email protected] Oxford Archaeological Unit Limited is a Registered Charity No: 285627 Disclaimer: This document has been prepared for the titled project or named part thereof and should not be relied upon or used for any other project without an independent check being carried out as to its suitability and prior written authority of Oxford Archaeology being obtained. Oxford Archaeology accepts no responsibility or liability for the consequences of this document being used for a purpose other than the purposes for which it was commissioned. Any person/party using or relying on the document for such other purposes agrees, and will by such use or reliance be taken to confirm their agreement to indemnify Oxford Archaeology for all loss or damage resulting therefrom. -

Social and Religious Jewish Non- Conformity: Representations of the Anglo-Jewish Experience in the Oral Testimony Archive of the Manchester Jewish Museum

SOCIAL AND RELIGIOUS JEWISH NON- CONFORMITY: REPRESENTATIONS OF THE ANGLO-JEWISH EXPERIENCE IN THE ORAL TESTIMONY ARCHIVE OF THE MANCHESTER JEWISH MUSEUM A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2019 Tereza Ward School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Contents Abbreviations.............................................................................................................. 5 Abstract ....................................................................................................................... 6 Declaration .................................................................................................................. 7 Copyright Statement .................................................................................................. 8 Acknowledgments ...................................................................................................... 9 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................... 10 1.1. The aims of this study .................................................................................. 10 1.2. A Brief history of Manchester Jewry: ‘the community’.............................. 11 1.3. Defining key terms ...................................................................................... 17 1.3.1. Problems with definitions of community and their implications for conformity ......................................................................................................... -

Mapping the Geographies of Manchester's Housing Problems

Mapping the geographies of Manchester’s housing problems and the twentieth century 3 solutions Martin Dodge “Manchester is a huge overgrown village, built according to no definite plan. The factories have sprung up along the rivers Irk, Irwell and Medlock, and the Rochdale Canal. The homes of the work-people have been built in the factory districts. The interests and convenience of the manufacturers have determined the growth of the town and the manner of that growth, while the comfort, health and happiness have not been consid- ered. … Every advantage has been sacrificed to the getting of money.” Dr. Roberton, a Manchester surgeon, in evidence to the Parliamentary Committee on the Health of Towns, 1840 (quoted in Bradshaw, 1987). The industrial city and its housing mid-nineteenth century, private estates of substan- conditions tial suburban villas were constructed, away from Where people live and the material housing the poverty and pollution of the inner industrial conditions they enjoy has been a central concern neighbourhoods. An example of these early to geographers, planners and scholars in housing suburban housing developments for the elites studies and urban sociology throughout the was Victoria Park, planned in 1837; large detached twentieth century. The multifaceted challenge mansions on tree lined avenues were built in the of adequately housing an expanding population 1840s and 1850s. The goal was to provide a sense has been at the heart of the history of Manchester of seclusion and tranquillity of countryside, but and its changing geography. From the city’s rapid with proximity to the city centre and commercial industrialisation in the 1780s onwards, through activity; gated entrances to estates were installed physical growth into a metropolis with global to enforce social exclusivity.