The Gulf's Early Economic Policy Response to the Crises of 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Arab Emirates

FREEDOM ON THE NET 2016 United Arab Emirates 2015 2016 Population: 9.2 million Not Not Internet Freedom Status Internet Penetration 2015 (ITU): 91 percent Free Free Social Media/ICT Apps Blocked: Yes Obstacles to Access (0-25) 14 14 Political/Social Content Blocked: Yes Limits on Content (0-35) 22 22 Bloggers/ICT Users Arrested: Yes Violations of User Rights (0-40) 32 32 TOTAL* (0-100) 68 68 Press Freedom 2016 Status: Not Free * 0=most free, 100=least free Key Developments: June 2015 – May 2016 • Authorities issued blocking orders against several overseas news websites over the past year, including Middle East Eye, The New Arab, and al-Araby al-Jadeed for unfavorable coverage of the country’s human rights abuses. Two Iran-based news sites were also blocked in a reflection of mounting tensions between the two countries (seeBlocking and Filtering). • A July 2015 law designed to combat discrimination and hate speech also outlines jail terms of six months to over 10 years and fines from US$ 14,000-550,000 for online posts deemed to insult “God, his prophets, apostles, holy books, houses of worship, or grave- yards” (see Legal Environment). • In June 2015, Nasser al-Faresi was sentenced to three years in jail for tweets found to have insulted the Federal Supreme Court and the ruler of Abu Dhabi. The court convicted him of “spreading rumors and information that harmed the country” (see Prosecutions and Detentions for Online Activities). • Academic and activist Dr. Nasser Bin Ghaith was arrested and held incommunicado until April 2016, when it was announced he was held on numerous charges, including “com- mitting a hostile act against a foreign state” for tweets that criticized Egypt’s treatment of political detainees (see Prosecutions and Detentions for Online Activities). -

Arabs at the Crossroads: Political Identity and Nationalism

Book Review of Hilal Khashan's Arabs at the Crossroads: Political Identity and Nationalism (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2000), The Arab World Geographer/Le Géographe du monde arabe 3(2):141-147, 2000. In the book Arabs at the Crossroads, Hilal Khashan, an associate professor of political science at the American University of Beirut, provides a vivid description of Arab political performance since the decline of the Ottoman Empire in the nineteenth century and the subsequent formal abrogation of the Islamic Caliphate in 1924 amidst rising European colonialism and Zionism. The book is small (149 pages of text) but concise and well written. Despite raising some very controversial issues, Khashan has combined the coolness of scholarship with intellectual rigor and political concern. His dispassionate perspective is refreshing and makes the book unapologetically independent and provocative. The book consists of nine chapters mostly focused on Arab political experience during the twentieth century. Chapter 1 examines the roots of the identity crisis in the Arab world, especially the ways in which “nineteenth-century reformers disturbed the Arab mind by sowing distrust in the Ottoman empire, without securing a tenable ideological alternative to that religious state and to Islam which it embodied” (page 1). Chapter 2 discusses the birth and the universalization of the European nation-state model of secular nationalism and its many incomplete versions in non-Western cultures, particularly in Muslim countries where “the clash between ethnocentrism and religion seems to resolve itself to the detriment of the former, without the latter emerging as a clear victor” (page 24). While this is a brilliant description of how modern Arab identity seems to swing constantly from Arab nationalism to Islamic identity and back, it stops short of an in-depth theoretical analysis of what constitutes the essence of identity in the Arab world. -

The Future of US Relations with the Gulf States

The Approaching Turning Point: The Future of U.S. Relations with the Gulf States By F. Gregory Gause, III Brookings Project on U.S. Policy Towards the Islamic World Analysis Paper Number Two, May 2003 1 Executive Summary United States policy toward the Gulf Cooperation Council states (Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Oman) is in the midst of an important change. Saudi Arabia has served as the linchpin of American military and political influence in the Gulf since Desert Storm. It can no longer play that role. After the attacks of September 11, 2001, an American military presence in the kingdom is no longer sustainable in the political system of either the United States or Saudi Arabia. Washington therefore has to rely on the smaller Gulf monarchies to provide the infrastructure for its military presence in the region. The build-up toward war with Iraq has accelerated that change, with the Saudis unwilling to cooperate openly with Washington on this issue. No matter the outcome of war with Iraq, the political and strategic logic of basing American military power in these smaller Gulf states is compelling. In turn, Saudi-American relations need to be reconstituted on a basis that serves the shared interests of both states, and can be sustained in both countries’ political systems. That requires an end to the basing of American forces in the kingdom. The fall of Saddam Hussein will facilitate this goal, allowing the removal of the American air wing in Saudi Arabia that patrols southern Iraq. The public opinion benefits for the Saudis of the departure of the American forces will permit a return to a more normal, if somewhat more distant, cooperative relationship with the United States. -

United Arab Emirates (Uae)

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: United Arab Emirates, July 2007 COUNTRY PROFILE: UNITED ARAB EMIRATES (UAE) July 2007 COUNTRY اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴّﺔ اﻟﻤﺘّﺤﺪة (Formal Name: United Arab Emirates (Al Imarat al Arabiyah al Muttahidah Dubai , أﺑﻮ ﻇﺒﻲ (The seven emirates, in order of size, are: Abu Dhabi (Abu Zaby .اﻹﻣﺎرات Al ,ﻋﺠﻤﺎن Ajman , أ مّ اﻟﻘﻴﻮﻳﻦ Umm al Qaywayn , اﻟﺸﺎرﻗﺔ (Sharjah (Ash Shariqah ,دﺑﻲّ (Dubayy) .رأس اﻟﺨﻴﻤﺔ and Ras al Khaymah ,اﻟﻔﺠﻴﺮة Fajayrah Short Form: UAE. اﻣﺮاﺗﻰ .(Term for Citizen(s): Emirati(s أﺑﻮ ﻇﺒﻲ .Capital: Abu Dhabi City Major Cities: Al Ayn, capital of the Eastern Region, and Madinat Zayid, capital of the Western Region, are located in Abu Dhabi Emirate, the largest and most populous emirate. Dubai City is located in Dubai Emirate, the second largest emirate. Sharjah City and Khawr Fakkan are the major cities of the third largest emirate—Sharjah. Independence: The United Kingdom announced in 1968 and reaffirmed in 1971 that it would end its treaty relationships with the seven Trucial Coast states, which had been under British protection since 1892. Following the termination of all existing treaties with Britain, on December 2, 1971, six of the seven sheikhdoms formed the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The seventh sheikhdom, Ras al Khaymah, joined the UAE in 1972. Public holidays: Public holidays other than New Year’s Day and UAE National Day are dependent on the Islamic calendar and vary from year to year. For 2007, the holidays are: New Year’s Day (January 1); Muharram, Islamic New Year (January 20); Mouloud, Birth of Muhammad (March 31); Accession of the Ruler of Abu Dhabi—observed only in Abu Dhabi (August 6); Leilat al Meiraj, Ascension of Muhammad (August 10); first day of Ramadan (September 13); Eid al Fitr, end of Ramadan (October 13); UAE National Day (December 2); Eid al Adha, Feast of the Sacrifice (December 20); and Christmas Day (December 25). -

Non-Indigenous Citizens and “Stateless” Residents in the Gulf

Andrzej Kapiszewski NON-INDIGENOUS CITIZENS AND "STATELESS" RESIDENTS IN THE GULF MONARCHIES. THE KUWAITI BIDUN Since the discovery of oil, the political entities of the Persian Gulf have transformed themselves from desert sheikhdoms into modern states. The process was accompanied by rapid population growth. During the last 50 years, the population of the current Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Oman1, grew from 4 million in 1950 to 33.4 million in 2004, thus recording one of the highest rates of population growth in the world2. The primary cause of this increase has not been the growth of the indigenous population, large in itself, but the influx of foreign workers. The employment of large numbers of foreigners was a structural imperative for growth in the GCC countries, as oil-related development depended upon the importation of foreign technologies, and reąuired knowledge and skills unfamiliar to the local Arab population. Towards the end of 2004, there were 12.5 million foreigners, 37 percent of the total population, in the GCC states. In Qatar, the UAE, and Kuwait, foreigners constituted a majority. In the United Arab Emirates foreigners accounted for over 80 percent of population. Only Oman and Saudi Arabia managed to maintain a relatively Iow proportion of foreign population: about 20 and 27 percent, respectively. This development has created security, economic, social and cultural threats to the local population. Therefore, to maintain the highly privileged position of the indigenous population and make integration of foreigners with local communities difficult, numerous restrictions were imposed: the sponsorship system, limits on the duration of every foreigner’s stay, curbs on naturalization and on the citizenship rights of those who are naturalized, etc. -

Gulf Affairs

Autumn 2016 A Publication based at St Antony’s College Identity & Culture in the 21st Century Gulf Featuring H.E. Salah bin Ghanem Al Ali Minister of Culture and Sports State of Qatar H.E. Shaikha Mai Al-Khalifa President Bahrain Authority for Culture & Antiquities Ali Al-Youha Secretary General Kuwait National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters Nada Al Hassan Chief of Arab States Unit UNESCO Foreword by Abdulaziz Saud Al-Babtain OxGAPS | Oxford Gulf & Arabian Peninsula Studies Forum OxGAPS is a University of Oxford platform based at St Antony’s College promoting interdisciplinary research and dialogue on the pressing issues facing the region. Senior Member: Dr. Eugene Rogan Committee: Chairman & Managing Editor: Suliman Al-Atiqi Vice Chairman & Partnerships: Adel Hamaizia Editor: Jamie Etheridge Chief Copy Editor: Jack Hoover Arabic Content Lead: Lolwah Al-Khater Head of Outreach: Mohammed Al-Dubayan Communications Manager: Aisha Fakhroo Broadcasting & Archiving Officer: Oliver Ramsay Gray Research Assistant: Matthew Greene Copyright © 2016 OxGAPS Forum All rights reserved Autumn 2016 Gulf Affairs is an independent, non-partisan journal organized by OxGAPS, with the aim of bridging the voices of scholars, practitioners, and policy-makers to further knowledge and dialogue on pressing issues, challenges and opportunities facing the six member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessar- ily represent those of OxGAPS, St Antony’s College, or the University of Oxford. Contact Details: OxGAPS Forum 62 Woodstock Road Oxford, OX2 6JF, UK Fax: +44 (0)1865 595770 Email: [email protected] Web: www.oxgaps.org Design and Layout by B’s Graphic Communication. -

Saudi Arabia – Industrial Sector Overview August 2016

Saudi Arabia – Industrial Sector Overview August 2016 WWW.JEG.ORG.SA Saudi Arabia – Industrial Sector Overview Report, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 06 1. Introduction 07 2. Saudi Arabia – Industry Overview 08 2.1 Industry 2020: The National Industrial Strategy 08 2.2 National Transformation Program 2020 09 3. Construction & Cement 10 3.1 Construction 10 3.1.1 Infrastructure Construction 12 3.1.2 Office Construction 12 3.1.3 Building Sector Construction 13 3.1.4 Oil & Gas Sector Construction 14 3.1.5 Power & Water Sector Construction 14 3.1.6 Industrial Construction 15 3.1.7 Retail Construction 15 3.1.8 Hospitality Construction Market 16 3.2 Top Construction Players in the Saudi Arabian Market 17 3.3 Construction Industry Drivers and Constraints 18 3.4 Regulatory Reforms in Construction Sector in Saudi Arabia 18 3.4.1 Green Building Regulations 18 3.4.2 Restrictions on Working Hours 19 3.5 SWOT Analysis 19 3.6 Cement 19 3.6.1 Major Market Players 21 3.6.2 Cement Sector – Issues 21 3.6.3 SWOT Analysis 22 4. Petrochemicals & Refineries 23 4.1 Petrochemicals 23 4.1.1 Major Market Players 24 4.1.2 SWOT Analysis 26 4.2 Refining 26 4.2.1 SWOT Analysis 27 5. Mining & Metals 28 5.1 Major Market Players 29 5.2 SWOT Analysis 29 6. Regulations and Ease of Doing Business 30 Saudi Arabia – Industrial Sector Overview Report, 2016 2 7. Industry – Outlook 31 7.1 Non-oil Sector Growth Contracts 31 7.2 Implications of Global Oil Market for Saudi Arabia 31 7.3 USD 4 Trillion Investment Needed to Sustain Job Demand in Non-oil Economy 31 7.4 Privatization and an Open Stock Exchange 31 8. -

The Special-Purpose Carrier of Pipe Joints

15JULY1988 MEED 25 Ramazarnanpour Ramazanianpour held talks Denktash. says he is ready for financial aspects of its offer. The group — with the ccfnmerce, heavy and light industry unconditional talks with Greek Cypnot Impreqilo, Cogefar and Gruppo m ministers arid visited the Iranian pavilion at the President George Vassiliou about the Industrie Elettromeccaniche per 24th Algiers international fair. future of the divided island. Impiantl all'Estero (GIE)—plans to start • The Mauntanian towns ot Ak|ou|t and Zouerat In March. Denktash insisted any talks work on the diversionary canal for the dam have received equipment including trucks, must be based on a proposal put forward m September (MEED 24:6:88). trailers, water tanks and tractors from their by UNSecretary-General Javier Perez de Bids for construction of the dam, which Algerian twin towns of Staoueli and Ouenza. Cuellar. The proposal has been reacted will replace the old Esna barrage, were by Greek Cypnots. submitted by 12 international groups in Denktash issued his statement on 6 July December 1986. The field was eventually after a three-day visit to Ankara, where he narrowed to three bidders — the Italian BAHRAIN met Turkey's President Evren and Prime group, Yugoslavia's Energoprojekt, and a Minister TurgutOzal. Canadian consortium of The SWC Group • Bahrain National Gas Company (Banagaa) Vassiliou has refused previous offers to and Canadian International produced 3.2 million barrels a day (b/d) ot Construction Corporation. liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) in 1987. This was meet Denktash on the grounds that the highest daily average since 1979 — its first unacceptable preconditions have been The Italian group brought in Switzerland's year of operations — and 5 percent up on the attached to any meeting. -

The Outlook for Arab Gulf Cooperation

The Outlook for Arab Gulf Cooperation Jeffrey Martini, Becca Wasser, Dalia Dassa Kaye, Daniel Egel, Cordaye Ogletree C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1429 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9307-3 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2016 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover image: Mideast Saudi Arabia GCC summit, 2015 (photo by Saudi Arabian Press Agency via AP). Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions.html. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface This report explores the factors that bind and divide the six Gulf Coop- eration Council (GCC) states and considers the implications of GCC cohesion for the region over the next ten years. -

Economic Update

Economic Update NBK Economic Research Department I 3 November 2020 Projects > Ensaf Al-Matrouk Research Assistant +965 2259 5366 Kuwait: Project awards pick up in 3Q as [email protected] > Omar Al-Nakib lockdown measures ease Senior Economist +965 2259 5360 [email protected] Highlights The value of project awards increased almost 82% q/q to KD 192 million in 3Q20. Projects awarded were transport and power/water-related; no oil/gas or construction projects were signed. KD 2.1bn worth of awards were penciled in for 2020, however, we expect a smaller figure to materialize. Project awards gather pace in 3Q20, but still fall short of However, with the economy experiencing only a partial recovery expectations so far the projects market is likely to remain subdued; only projects essential to the development plan are likely to be After reaching a multi-year low of KD 106 million in 2Q20, a prioritized. (Chart 3.) quarter that saw business activity heavily impacted by the coronavirus pandemic, the value of project awards increased . Chart 2: Annual project awards nearly 82% q/q in 3Q20 to reach KD 192 million. This is still KD billion, *includes awarded and planned modest by previous standards, however, and is 45% lower than 9 9 the KD 350 million worth of projects approved in in 3Q19. (Chart 8 Transport 8 Power & Water 1). One project award from the Ministry of Public Works’ (MPW), 7 7 accounted for the bulk (86%) of total project awards in the Oil & Gas 6 Construction 6 quarter. 5 Industrial 5 Total projects awarded in 2020 so far stand at KD 866 million 4 4 (cumulative), with about KD 1.3 billion still planned for 4Q20. -

Saudi – Israeli Nexus

ABOUT İRAM SAUDI – ISRAELI NEXUS: Center for Iranian Studies in Ankara is a non-prot research center IMPLICATIONS FOR IRAN dedicated to promoting innovative research and ideas on Iranian aairs. Our mission is to conduct in-depth research to produce up-to-date and accurate knowledge about Iran’s politics, economy and society. İRAM’s research agenda is guided by three key princi- ples – factuality, quality and responsibility. Arhama Siddiqa Muhammad Abbas Hassan Asad Ullah Khan Oğuzlar Mh. 1397. Sk. No: 14 06520 Çankaya, Balgat, Ankara, Turkey Phone: +90 312 284 55 02 - 03 Fax: +90 312 284 55 04 e-mail: [email protected] www.iramcenter.org All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted without the prior written permission of İRAM. Perspective May 2019 Copyright © 2019 Center for Iranian Studies in Ankara (İRAM). All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be fully reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published or broadcast without the prior written permission from İRAM. For electronic copies of this publication, visit iramcenter.org. Partial reproduction of the digital copy is possibly by giving an active link to www.iramcenter.org The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of İRAM, its staff, or its trustees. For electronic copies of this report, visit www. iramcenter.org. Editor : Serhan Afacan Graphic Design : Hüseyin Kurt Center for Iranian Studies in Ankara Oğuzlar, 1397. St, 06520, Çankaya, Ankara / Türkiye Phone: +90 (312) 284 55 02-03 | Fax: +90 (312) 284 55 04 e-mail : [email protected] | www.iramcenter.org Saudi – Israeli Nexus: Implications for Iran Suudi – İsrail İlişkilerinin İran’a Etkileri روابط عربستان سعودی و اسرائیل و پیامدهای آن برای ایران Arhama Siddiqa Arhama Siddiqa is a Research Fellow at The Institute of Strategic Studies Islamabad (ISSI). -

42 MEED Listfinal.Indd

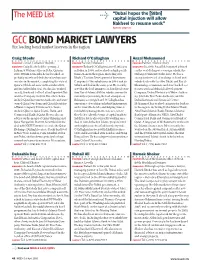

“Dubai hopes the [$8bn] The MEED List Q capital injection will allow Nakheel to resume work” Agenda page 20 GCC BOND MARKET LAWYERS Six leading bond market lawyers in the region Craig Stoehr Richard O’Callaghan Anzal Mohammed POSITION Counsel, Latham & Watkins POSITION Partner, Linklaters POSITION Partner, Allen & Overy BIOGRAPHY Craig Stoehr led the opening of BIOGRAPHY Richard O’Callaghn joined Linklaters BIOGRAPHY In 2009, Anzal Mohammed advised Latham & Watkins office in Doha, Qatar in in Dubai in 2008, and worked on high-profile on the world’s largest sovereign sukuk, the 2008. Within 12 months he had worked on transactions in the region, including Abu Dubai government’s $2bn issue. He has a probably more bond deals by value than any- Dhabi’s Tourism Development & Investment strong track-record of working on bond and one else in the market, completing the state of Company’s $1bn sukuk issue in 2009, and its sukuk deals with the Abu Dhabi and Ras al- Qatar’s $7bn bond issue in November 2009, $1bn bond deal in the same year. He recently Khaimah governments, and state-backed cor- and its earlier $3bn deal. Stoehr also worked acted for the lead arrangers on Saudi real estate porates such as Mubadala Development on a $2.3bn bond for Ras Laffan Liquefied Nat- firm Dar al-Arkan’s $450m sukuk issue and is Company, Dubai Electricity & Water Author- ural Gas Company in 2009. His other clients currently representing the lead arrangers on ity, Jebel Ali Free Zone Authority, and the include Qatar Investment Authority, and state- Bahrain’s sovereign bond.