Barnaby Haran When Paul Strand Wa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Finding Aid to the Elizabeth Mccausland Papers, 1838-1995, Bulk 1920-1960, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Elizabeth McCausland Papers, 1838-1995, bulk 1920-1960, in the Archives of American Art Jennifer Meehan and Judy Ng Funding for the processing and digitization of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art April 12, 2006 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 3 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 4 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 5 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 5 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 7 Series 1: Personal Papers, 1838, 1920-1951.......................................................... 7 Series 2: Correspondence, 1923-1960.................................................................. 10 Series 3: General -

American Paintings, 1900–1945

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS American Paintings, 1900–1945 American Paintings, 1900–1945 Published September 29, 2016 Generated September 29, 2016 To cite: Nancy Anderson, Charles Brock, Sarah Cash, Harry Cooper, Ruth Fine, Adam Greenhalgh, Sarah Greenough, Franklin Kelly, Dorothy Moss, Robert Torchia, Jennifer Wingate, American Paintings, 1900–1945, NGA Online Editions, http://purl.org/nga/collection/catalogue/american-paintings-1900-1945/2016-09-29 (accessed September 29, 2016). American Paintings, 1900–1945 © National Gallery of Art, Washington National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS American Paintings, 1900–1945 CONTENTS 01 American Modernism and the National Gallery of Art 40 Notes to the Reader 46 Credits and Acknowledgments 50 Bellows, George 53 Blue Morning 62 Both Members of This Club 76 Club Night 95 Forty-two Kids 114 Little Girl in White (Queenie Burnett) 121 The Lone Tenement 130 New York 141 Bluemner, Oscar F. 144 Imagination 152 Bruce, Patrick Henry 154 Peinture/Nature Morte 164 Davis, Stuart 167 Multiple Views 176 Study for "Swing Landscape" 186 Douglas, Aaron 190 Into Bondage 203 The Judgment Day 221 Dove, Arthur 224 Moon 235 Space Divided by Line Motive Contents © National Gallery of Art, Washington National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS American Paintings, 1900–1945 244 Hartley, Marsden 248 The Aero 259 Berlin Abstraction 270 Maine Woods 278 Mount Katahdin, Maine 287 Henri, Robert 290 Snow in New York 299 Hopper, Edward 303 Cape Cod Evening 319 Ground Swell 336 Kent, Rockwell 340 Citadel 349 Kuniyoshi, Yasuo 352 Cows in Pasture 363 Marin, John 367 Grey Sea 374 The Written Sea 383 O'Keeffe, Georgia 386 Jack-in-Pulpit - No. -

A Thesis Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board in Partial

ABSTRACT My thesis seeks to broaden the framework of conversation surrounding Berenice Abbott’s Changing New York. Much scholarship regarding Changing New York has focused on the individual photographs, examined and analyzed as independent of the meticulously arranged whole. My thesis considers the complete photo book, and how the curated pages work together to create a sort of guide of the city. Also, it has been continually noted that Abbott was a member of many artistic circles in New York City in the early 1930s, but little has been written analyzing how these relationships affected her artistic eye. Building on the scholarship of art historian Terri Weissman, my thesis contextualizes Abbott’s working environment to demonstrate how Abbott’s particular adherence to documentary photography allowed her to transcribe the urban metamorphosis. Turning to the scholarship of Peter Barr, I expand on his ideas regarding Abbott’s artistic relationship to the architectural and urban planning theories of Lewis Mumford and Henry-Russell Hitchcock. Abbott appropriated both Mumford and Hitchcock’s theories on the linear trajectory of architecture, selecting and composing her imagery to fashion for the viewer a decipherable sense of the built city. Within my thesis I sought to link contemporary ideas of the after-image proposed by Juan Ramon Resina to Abbott’s chronicling project. By using this framework I hope to show how Abbott’s photographs are still relevant to understanding the ever-changing New York City. ! ii! ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank Dr. Silk for his support during the last two years. From my first proposal for this project to what was actually produced, he was always there to listen to my ideas and guide me in a positive direction. -

Modern Photographs the Thomas Walther Collection 1909 – 1949

abbaspour Modern Photographs Daffner The Thomas Walther Collection hambourg 1909 – 1949 Modern Photographs OBJECT Mitra Abbaspour is Associate Curator of Photography, The period between the first and second world wars saw The Museum of Modern Art. a dynamic explosion of photographic vision on both sides of the Atlantic. Imaginative leaps fused with tech- Lee Ann Daffner is Andrew W. Mellon Conservator of nological ones, such as the introduction of small, fast, Photography, The Museum of Modern Art. easily portable cameras, to generate many novel ways Maria Morris Hambourg, the founding curator of the of taking and making images. These developments— Department of Photographs at The Metropolitan which constitute a key moment in modern art, and are Museum of Art, is Senior Curator for the Walther project, the foundation of today’s photo-based world—are dra- The Museum of Modern Art. matically captured in the 341 photographs in the Thomas Walther Collection at The Museum of Modern Art. Object:Photo explores these brilliant images using Quentin Bajac is Joel and Anne Ehrenkranz Chief Curator : The Thomas Walther Collection Collection Walther Thomas The a new approach: instead of concentrating on their con- of Photography, The Museum of Modern Art. tent it also considers them as objects, as actual, physical PHOTO Jim Coddington is Agnes Gund Chief Conservator, the things created by individuals using specific techniques Department of Conservation, The Museum of Modern Art. at particular places and times, each work with its own unique history. Essays by both conservators and histori- Ute Eskildsen is Deputy Director and Head of ans provide new insight into the material as well as the Photography emeritus, Museum Folkwang, Essen. -

5. Main Body of Text

The Politics and Poetics of Children’s Play: Helen Levitt’s Early Work By Elizabeth Margaret Gand A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Emerita Anne Wagner, Chair Professor Emeritus Tim Clark Professor Elizabeth Abel Spring 2011 The Politics and Poetics of Children’s Play: Helen Levitt’s Early Work Copyright 2011 by Elizabeth Margaret Gand Abstract The Politics and Poetics of Children’s Play: Helen Levitt’s Early Work by Elizabeth Margaret Gand Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art University of California, Berkeley Professor Emerita Anne Middleton Wagner, Chair This dissertation examines the work of the American photographer, Helen Levitt. It focuses in particular on her first phase of production—the years from 1937 to 1943—when she developed an important archive of pictures documenting children’s art and play encountered in the city streets. The dissertation is designed to help us understand the reasons why the subject of urban children’s art and play proved so productive for Levitt in her first phase of work. Why did she return again and again to the sight of children at play in the city streets? Why did she expend so much effort collecting children’s rude and crude drawings found on the pavement and the brownstone walls? What led her to envision the child as her genius loci of the urban streets, and what did she make out of the subject? Chapter one situates Helen Levitt’s initial turn to the child in relation to a surge of child imagery that appeared in the visual culture of the 1930s. -

Lewis Hine and „Social Photography‟

The Narrative Document: Lewis Hine and „Social Photography‟ By Kathy A. Quick B.F.A., University of Connecticut, 1989 M.A.L.S., Wesleyan University, 1994 M.A., University of Massachusetts Amherst, 2001 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May 2010 © Copyright 2010 by Kathy A. Quick This dissertation by Kathy A. Quick is accepted in its present form by the Department of the History of Art and Architecture as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date__________ ________________________________________ Mary Ann Doane, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date__________ ________________________________________ Douglas R. Nickel, Reader Date__________ ________________________________________ Dian Kriz, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date__________ ________________________________________ Sheila Bonde, Dean of the Graduate School iii Abstract of “The Narrative Document: Lewis Hine and „Social Photography‟” by Kathy A. Quick, Ph.D., Brown University, May 2010 Lewis Hine employed a variety of narrative strategies to create a persuasive and moving „social photography‟ in the early twentieth century. Despite the longstanding supposition within the history of photography that the categories of documentary and narrative are incompatible, this investigation looks at how Hine cultivated, rather than suppressed narrative in his documentary work. Documentary has often been associated with unmanipulated authenticity and with the unmediated transcription of reality. Unlike the concept of narrative which is virtually inseparable from that of fiction, documentary is tied to a belief in the camera‟s ability to present empirical evidence or facts. -

Engendered Modern the Urban Landscapes of Georgia O’Keeffe, Florine Stettheimer, and Bernice Abbott

ENGENDERED MODERN THE URBAN LANDSCAPES OF GEORGIA O’KEEFFE, FLORINE STETTHEIMER, AND BERNICE ABBOTT A Thesis Submitted to The Temple University Graduate Board _____________________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ______________________________________________________________________ by Kristina Rose Murray August 2018 Dr. Erin Pauwels, Thesis Advisor, Department of Art History Dr. Gerald Silk, Department of Art History ABSTRACT This thesis explores the dynamic relationship between artists Georgia O’Keeffe, Florine Stettheimer, and Berenice Abbott in relation to the growing urban landscape of New York City in the 1920s and 1930s. Previous scholarship has drawn parallels between these three artists’ careers solely in terms related to their biography and gender identity rather than their work. In contrast, my project identifies a common formal subject that links an experimental phase in all three women’s work, and explores the reasons these three individual creators found portraying the city to be an effective strategy for developing her own take on modernist style. Inspired by rapid development, each artist made work that shared her inventive vision of the city. Using visual analysis and historical context associated with the second wave of skyscraper construction as well as the second generation “New Woman” movement, I argue that each artist produced idiosyncratic art that makes sense of the rapidly morphing city surrounding them. Eschewing conventional gender expectations and traditional art historical narratives, the three artists tell visual stories that illustrate life in a modern urban city. Each woman’s goals and artistic expectations differ, but they all share the struggle to achieve professionally despite systemic roadblocks placed before them by the male-dominated art world. -

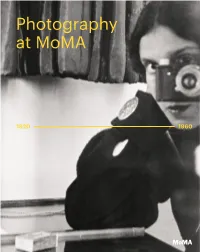

Read a Free Sample

Photography at MoMA Contributors Quentin Bajac is The Joel and Anne Ehrenkranz Chief Curator of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Museum of Modern Art draws upon the exceptional depth of its collection to tell a new history of photography in the three-volume series Photography at MoMA. Douglas Coupland is a Vancouver-based artist, writer, and cultural critic. The works in Photography at MoMA: 1920–1960 chart the explosive development Lucy Gallun is Assistant Curator in the Department of the medium during the height of the modernist period, as photography evolved of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, from a tool of documentation and identification into one of tremendous variety. New York. The result was nothing less than a transformed rapport with the visible world: Roxana Marcoci is Senior Curator in the Department Walker Evans's documentary style and Dora Maar's Surrealist exercises in chance; of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, El Lissitzky's photomontages and August Sander's unflinching objectivity; New York. the iconic news images published in the New York Times and Man Ray's darkroom experiments; Tina Modotti's socioartistic approach and anonymous snapshots Sarah Hermanson Meister is Curator in the Department of Photography at The Museum taken by amateur photographers all over the world. In eight chapters arranged of Modern Art, New York. by theme, this book presents more than two hundred artists, including Berenice Abbott, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Geraldo de Barros, Margaret Bourke-White, Kevin Moore is an independent curator, writer, Bill Brandt, Claude Cahun, Harry Callahan, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Roy DeCarava, and advisor in New York. -

WALKER EVANS in NEW YORK: PHOTOGRAPHY and URBAN CULTURE, 1927–1934 Antonello Frongia, Ph.D

WALKER EVANS IN NEW YORK: PHOTOGRAPHY AND URBAN CULTURE, 1927–1934 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Antonello Frongia August 2015 © 2015 Antonello Frongia ALL RIGHTS RESERVED WALKER EVANS IN NEW YORK: PHOTOGRAPHY AND URBAN CULTURE, 1927–1934 Antonello Frongia, Ph.D. Cornell University, 2015 This dissertation offers the first systematic study of the photographs taken by Walker Evans in New York City and its vicinity between 1927 and 1934, a formative period that preceded the full consecration of his work in the second half of the 1930s. About 200 urban photographs in the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum and a significant body of negatives in the Metropolitan Museum’s Walker Evans Archive indicate that Evans’s early work was mostly devoted to the theme of the modern me- tropolis. Cross-referencing Evans’s images with contemporary photographs, aerial views, architectural plans, insurance maps, drawings, and verbal descriptions, this study aims to identify the exact subjects, the places, and whenever possible the dates of this previ- ously uncharted body of urban photographs. The resulting catalog of over 300 images suggests the contours of an unfinished project on New York City that Evans developed in the years immediately preceding and following the Wall Street crash of 1929. On a different level, this dissertation addresses the question of Evans’s visual educa- tion in the context of the “transatlantic modernism” of the 1920s and ’30s. In particular, it shows that Evans, despite his early literary ambitions, was fully conversant with the work of visual artists, architects, and critics of the Machine Age. -

Rebecca Salsbury James, Folk Art, and Modernism in the United States

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Fall 1-5-2021 Quality and Simplicity: Rebecca Salsbury James, Folk Art, and Modernism in the United States Caroline Seabolt CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/660 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Quality and Simplicity: Rebecca Salsbury James, Folk Art, and Modernism in the United States by Caroline Seabolt Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History, Hunter College The City University of New York November 9, 2020 Emily Braun Date Thesis Sponsor November 13, 2020 Katherine Manthorne Date Second Reader TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................................................................. II LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ........................................................................................................ III INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER ONE: BEAUTIFUL AND DIFFERENT: REVERSE PAINTING ON GLASS AND THE EARLY STILL LIFES, 1929-1933...................................................................................... 32 CHAPTER TWO: SPANISH SOUTHWESTERN