Legal Education and the Civil Law System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core Principles of the Legal Profession

CORE PRINCIPLES OF THE LEGAL PROFESSION Resolution ratified on Tuesday October 30, 2018, during the General Assembly in Porto Preamble The lawyer’s role is to counsel, conciliate, represent and defend. In a society founded on respect for the law and for justice, the lawyer advises the client on legal matters, examines the possibility and the appropriateness of finding amicable solutions or of choosing an alternative dispute resolution method, assists the client and represents the client in legal proceedings. The lawyer fulfils the lawyer’s engagement in the interest of the client while respecting the rights of the parties and the rules of the profession, and within the boundaries of the law. Over the years, each bar association has adopted its own rules of conduct, which take into account national or local traditions, procedures and laws. The lawyer should respect these rules, which, notwithstanding their details, are based on the same basic values set forth below. 1 - Independence of the lawyer and of the Bar In order to fulfil fully the lawyer’s role as the counsel and representative of the client, the lawyer must be independent and preserve his lawyer’s professional and intellectual independence with regard to the courts, public authorities, economic powers, professional colleagues and the client, as well as regarding the lawyer’s own interests. The lawyer’s independence is guaranteed by both the courts and the Bar, according to domestic or international rules. Except for instances where the law requires otherwise to ensure due process or to ensure the defense of persons of limited means, the client is free to choose the client’s lawyer and the lawyer is free to choose whether to accept a case. -

Middle School and High School Lesson Plan on the Sixth Amendment

AMERICAN CONSTITUTION SOCIETY (ACS) CONSTITUTION IN THE CLASSROOM SIXTH AMENDMENT RIGHT TO COUNSEL MIDDLE & HIGH SCHOOL CURRICULUM — SPRING 2013 Lesson Plan Overview Note: times are approximate. You may or may not be able to complete within the class period. Be flexible and plan ahead — know which activities to shorten/skip if you are running short on time and have extra activities planned in case you move through the curriculum too quickly. 1. Introduction & Background (3-5 min.) .................................................. 1 2. Hypo 1: The Case of Jasper Madison (10-15 min.) ................................ 1 3. Pre-Quiz (3-5 min.) ................................................................................. 3 4. Sixth Amendment Text & Explanation (5 min.) ..................................... 4 5. Class Debate (20 min.) ........................................................................... 5 6. Wrap-up/Review (5 min.)....................................................................... 6 Handouts: Handout 1: State v. Jasper Madison ........................................................... 7 Handout 2: Sixth Amendment of the United States Constitution .............. 8 Handout 3: Franklin Adams’s Disciplinary Hearing ..................................... 9 Handout 4: The Case of Gerald Gault ....................................................... 10 Before the lesson: Ask the teacher if there is a seating chart available. Also ask what the students already know about the Constitution as this will affect the lesson -

Lawyers and Their Work: an Analysis of the Legal Profession in the United States and England, by Quintin Johnstone and Dan Hopson

Indiana Law Journal Volume 43 Issue 4 Article 9 Summer 1968 Lawyers and Their Work: An Analysis of the Legal Profession in the United States and England, by Quintin Johnstone and Dan Hopson Edwin O. Smigel New York University Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Smigel, Edwin O. (1968) "Lawyers and Their Work: An Analysis of the Legal Profession in the United States and England, by Quintin Johnstone and Dan Hopson," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 43 : Iss. 4 , Article 9. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol43/iss4/9 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOOK REVIEWS conclude with the observation that much more study and speculation on the needs and possibilities for use and development of what has been called transnational law are needed. A. A. FATouRost LAWYERS AND THEIR WORK: ANALYSIS OF THE LEGAL PROFESSION IN THE UNITED STATES AND ENGLAND. By Quintin Johnstone and Dan Hopson, Jr. Indianapolis, Kansas City, New York: Bobbs-Merrill Co. 1967. Pp. x, 604. $10.00. The task Johnstone and Hopson set for themselves is monumental. They seek to determine the goals for the legal profession; to present a picture of its work and specializations; to offer alternatives for providing legal services; and to describe the legal profession in England, primarily as a mirror which might point up the strengths and weaknesses of the American legal system. -

Marking 200 Years of Legal Education: Traditions of Change, Reasoned Debate, and Finding Differences and Commonalities

MARKING 200 YEARS OF LEGAL EDUCATION: TRADITIONS OF CHANGE, REASONED DEBATE, AND FINDING DIFFERENCES AND COMMONALITIES Martha Minow∗ What is the significance of legal education? “Plato tells us that, of all kinds of knowledge, the knowledge of good laws may do most for the learner. A deep study of the science of law, he adds, may do more than all other writing to give soundness to our judgment and stability to the state.”1 So explained Dean Roscoe Pound of Harvard Law School in 1923,2 and his words resonate nearly a century later. But missing are three other possibilities regarding the value of legal education: To assess, critique, and improve laws and legal institutions; To train those who pursue careers based on legal training, which may mean work as lawyers and judges; leaders of businesses, civic institutions, and political bodies; legal academics; or entre- preneurs, writers, and social critics; and To advance the practice in and study of reasoned arguments used to express and resolve disputes, to identify commonalities and dif- ferences, to build institutions of governance within and between communities, and to model alternatives to violence in the inevi- table differences that people, groups, and nations see and feel with one another. The bicentennial of Harvard Law School prompts this brief explo- ration of the past, present, and future of legal education and scholarship, with what I hope readers will not begrudge is a special focus on one particular law school in Cambridge, Massachusetts. ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– ∗ Carter Professor of General Jurisprudence; until July 1, 2017, Morgan and Helen Chu Dean and Professor, Harvard Law School. -

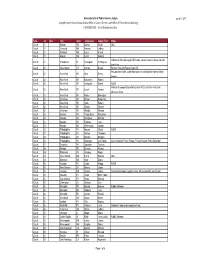

Anecdotal List of Public Interest Judges Compiled by the Harvard

Anecdotal List of Public Interest Judges as of 11/3/17 Compiled by the Harvard Law School Office of Career Services and Office of Public Interest Advising. CONFIDENTIAL - for HLS Applicants Only Type Cir Dist City State Judge Last Judge First Notes Circuit 01 Boston MA Barron David OLC Circuit 01 Concord NH Howard Jeffrey Circuit 01 Portland ME Lipez Kermit Circuit 01 Boston MA Lynch Sandra Worked at Harvard Legal Aid Bureau; started career in legal aid and Circuit 01 Providence RI Thompson O. Rogeree family law Circuit 02 New Haven CT Carney Susan Former Yale and Peace Corps GC Has partnered with Judge Katzmann on immigration representation Circuit 02 New York NY Chin Denny project Circuit 02 New York NY Katzmann Robert Circuit 02 New York NY Livingston Debra AUSA Worked as cooperating attorney with ACLU and New York Civil Circuit 02 New York NY Lynch Gerard Liberties Union Circuit 02 New York NY Parker Barrington Circuit 02 Syracuse NY Pooler Rosemary Circuit 02 New York NY Sack Robert Circuit 02 New York NY Straub Chester Circuit 02 Geneseo NY Wesley Richard Circuit 03 Newark NJ Trump Barry Maryanne Circuit 03 Newark NJ Chagares Michael Circuit 03 Newark NJ Fuentes Julio Circuit 03 Newark NJ Greenaway Joseph Circuit 03 Philadelphia PA Krause Cheryl AUSA Circuit 03 Philadelphia PA McKee Theodore Circuit 03 Philadelphia PA Rendell Marjorie Circuit 03 Philadelphia PA Restrepo Luis Felipe ACLU National Prison Project; Former Federal Public Defender Circuit 03 Scranton PA Vanaskie Thomas Circuit 04 Raleigh NC Duncan Allyson Circuit 04 Richmond -

Master of Laws

APPLYING FOR & FINANCING YOUR LLM MASTER OF LAWS APPLICATION REQUIREMENTS APPLICATION CHECKLIST Admission to the LLM program is highly For applications to be considered, they must include the following: competitive. To be admitted to the program, ALL APPLICANTS INTERNATIONAL APPLICANTS applicants must possess the following: • Application & Application Fee – apply • Applicants with Foreign Credentials - For electronically via LLM.LSAC.ORG, and pay applicants whose native language is not • A Juris Doctor (JD) degree from an ABA-accredited non-refundable application fee of $75 English and who do not posses a degree from law school or an equivalent degree (a Bachelor of Laws • Official Transcripts: all undergraduate and a college or university whose primary language or LL.B.) from a law school outside the United States. graduate level degrees of instruction is English, current TOEFL or IELTS • Official Law School or Equivalent Transcripts scores showing sufficient proficiency in the • For non-lawyers interested in the LLM in Intellectual • For non-lawyer IP professionals: proof of English language is required. The George Mason Property (IP) Law: a Bachelor’s degree and a Master’s minimum of four years professional experience University Scalia Law School Institution code degree in another field, accompanied by a minimum in an IP-related field is 5827. of four years work experience in IP may be accepted in • 500-Word Statement of Purpose • TOEFL: Minimum of 90 in the iBT test lieu of a law degree. IP trainees and Patent Examiners • Resume (100 or above highly preferred) OR (including Bengoshi) with four or more years of • Letters of Recommendation (2 required) • IELTS: Minimum of 6.5 (7.5 or above experience in IP are welcome to apply. -

The Place of Skills in Legal Education*

THE PLACE OF SKILLS IN LEGAL EDUCATION* 1. SCOPE AND PURPOSE OF THE REPORT. There is as yet little in the way of war or post-war "permanent" change in curriculum which is sufficiently advanced to warrant a sur- vey of actual developments. Yet it may well be that the simpler curricu- lum which has been an effect of reduced staff will not be without its post-war effects. We believe that work with the simpler curriculum has made rather persuasive two conclusions: first, that the basic values we have been seeking by case-law instruction are produced about as well from a smaller body of case-courses as from a larger body of them; and second, that even when classes are small and instruction insofar more individual, we still find difficulty in getting those basic values across, throughout the class, in terms of a resulting reliable and minimum pro- fessional competence. We urge serious attention to the widespread dis- satisfaction which law teachers, individually and at large, have been ex- periencing and expressing in regard to their classes during these war years. We do not believe that this dissatisfaction is adequately ac- counted for by any distraction of students' interest. We believe that it rests on the fact that we have been teaching classes which contain fewer "top" students. We do not believe that the "C" students are either getting materially less instruction-value or turning in materially poorer papers than in pre-war days. What we do believe is that until recently the gratifying performance of our best has floated like a curtain between our eyes and the unpleasant realization of what our "lower half" has not been getting from instruction. -

Joint Public Health and Law Programs

JOINT PUBLIC HEALTH AND LAW tuition rate and fees are charged for semesters when no Law School courses are taken, including summer sessions. PROGRAMS Visit the Hirsh Program website (http://publichealth.gwu.edu/ Program Contact: J. Teitelbaum programs/joint-jdllm-mphcertificate/) for additional information. The Milken Institute of School of Public Health (SPH), through its Hirsh Health Law and Policy Program, cooperates with the REQUIREMENTS Law School to offer public health and law students multiple programs that foster an interdisciplinary approach to the study MPH requirements in the joint degree programs of health policy, health law, public health, and health care. The course of study for the standalone MPH degree, in one of Available joint programs include the master of public health several focus areas, (http://publichealth.gwu.edu/node/766/) (http://bulletin.gwu.edu/public-health/#graduatetext) (MPH) consists of 45 credits, including a supervised practicum. In the and juris doctor (https://www.law.gwu.edu/juris-doctor/) (JD); dual degree programs with the Law School, the Milken Institute MPH and master of laws (https://www.law.gwu.edu/master- School of Public Health (GWSPH) accepts 8 Law School credits of-laws/) (LLM); and JD or LLM and SPH certificate in various toward completion of the MPH degree. Therefore, Juris doctor subject areas. LLM students may be enrolled in either the (JD) and master of laws (LLM) students in the dual program general or environmental law program at the Law School. complete only 37 credits of coursework through GWSPH to obtain an MPH degree. Application of credits between programs Depending upon the focus area in which a JD student chooses For the JD/MPH, 8 JD credits are applied toward the MPH and to study, as a rule, the joint degree can be earned in three- up to 12 MPH credits may be applied toward the JD. -

The Role of Lawyers in Producing the Rule of Law: Some Critical Reflections*

The Role of Lawyers in Producing the Rule of Law: Some Critical Reflections* Robert W Gordon** INTRODUCTION For the last fifteen years, American and European governments, lending institutions led by the World Bank, and NGOs like the American Bar Association have been funding projects to promote the "Rule of Law" in developing countries, former Communist and military dictatorships, and China. The Rule of Law is of course a very capacious concept, which means many different things to its different promoters. Anyone who sets out to investigate its content will soon find himself in a snowstorm of competing definitions. Its barebones content ("formal legality") is that of a regime of rules, announced in advance, which are predictably and effectively applied to all they address, including the rulers who promulgate them - formal rules that tell people how the state will deploy coercive force and enable them to plan their affairs accordingly. The slightly-more-than barebones version adds: "applied equally to everyone."' This minimalist version of the Rule of Law, which we might call pure positivist legalism, is not, however, what the governments, multilateral * This Article is based on the second Annual Cegla Lecture on Legal Theory, delivered at Tel Aviv University Faculty of Law on April 23, 2009. ** Chancellor Kent Professor of Law and Legal History, Yale University. I am indebted to the University of Tel Aviv faculty for their generous hospitality and helpful comments, and especially to Assaf Likhovski, Roy Kreitner, Ron Harris, Hanoch Dagan, Daphna Hacker, David Schorr, Daphne Barak-Erez and Michael Zakim. 1 See generallyBRIAN TAMANAHA, ON THE RULE OF LAW: HISTORY, POLITICS, THEORY 26-91 (2004) (providing a lucid inventory of the various common meanings of the phrase). -

Corporate Governance

CCCorporateCorporate Governance Carsten Burhop Universität zu KKölnölnölnöln Marc Deloof University of Antwerp 1. General introduction Since the late 1990s, a series of papers published in leading economics and finance journals contain evidence for a significant impact of institutions on financial and economic development (e.g., Acemoglu et al., 2001, 2005; La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny – LLSV henceforth – 1997, 1998, 2000; La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer – LLS henceforth – 1999, 2008). According to this literature, high-quality institutions cause financial development. In turn, financial development is a driving force behind economic growth. The historical legacy seems to play an important role in the relationship between the financial development of countries, their current institutions and their past institutions. Indeed, prominent contributions demonstrate a strong positive correlation between legal origins (common law is considered to be better than civil law) and three further elements: first, current indices of the rule of law (Acemoglu et al., 2001; Beck et al., 2003); second, financial development (LLSV 1997, 1998; Beck et al, 2003); and third, the dispersion of share ownership and the separation of ownership and control (LLS 1999). In general, shareholders are supposed to have the strongest protection in common-law countries, followed by German-style civil- law countries. Shareholder protection is the weakest in French style civil law countries. In contrast, secured creditors are supposed to be best protected in the German legal system. Consequently, common-law countries have relatively high numbers of listed firms and of initial public offerings and a relatively high ratio of stock market capitalisation to GDP. -

The Genius of Roman Law from a Law and Economics Perspective

THE GENIUS OF ROMAN LAW FROM A LAW AND ECONOMICS PERSPECTIVE By Juan Javier del Granado 1. What makes Roman law so admirable? 2. Asymmetric information and numerus clausus in Roman private law 2.1 Roman law of property 2.1.1 Clearly defined private domains 2.1.2 Private management of resources 2.2 Roman law of obligations 2.2.1 Private choices to co-operate 2.2.2 Private choices to co-operate without stipulating all eventualities 2.2.3 Private co-operation within extra-contractual relationships 2.2.4 Private co-operation between strangers 2.3 Roman law of commerce and finance 3. Private self-help in Roman law procedure 4. Roman legal scholarship in the restatement of civil law along the lines of law and economics 1. What makes Roman law so admirable? Law and economics aids us in understanding why Roman law is still worthy of admiration and emulation, what constitutes the “genius” of Roman law. For purposes of this paper, “Roman law” means the legal system of the Roman classical period, from about 300 B.C. to about 300 A.D. I will not attempt the tiresome job of being or trying to be a legal historian in this paper. In the manner of German pandect science, let us stipulate that I may arbitrarily choose certain parts of Roman law as being especially noteworthy to the design of an ideal private law system. This paper discusses legal scholarship from the ius commune. It will also discuss a few Greek philosophical ideas which I believe are important in the Roman legal system. -

104 (I) / 2003 the Marriage Law Arrangement of Sections

Translation: Union of Cyprus Municipalities Official Gazette Annex I (I) No. 3742, 25.7.2003 Law: 104 (I) / 2003 THE MARRIAGE LAW ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Sections PART I PRELIMINARY 1. Short Title 2. Interpretation PART II MARRIAGE 3. Contract of marriage PART III NOTICE OF INTENDED MARRIAGE 4. Notice of intended marriage 5. Filing of Notice 6. Issue of certificates of notice 7. Marriage to be celebrated at earlier date 8. Declaration of parties that there is no impediment PART IV MARRIAGE CEREMONY 9. Marriage Ceremony 10. Refusal to celebrate a marriage 11. Selection of place 12. Marriage certificate PART V CONDITIONS AND RESTRICTIONS FOR THE CELEBRATION OF MARRIAGE-FAULTY MARRIAGES 13. Categories of faulty marriages 14. Voidable marriages 15. Age for marriage 16. Lifting of voidability 17. Void marriages 18. Dissolution or annulment of previous marriage 19. Nonexistent marriages Translation: Union of Cyprus Municipalities PART VI VOID MARRIAGES 20. Application of this Part 21. Action for annulment 22. Right to file action 23. Lifting of annulment 24. Result of annulment 25. Status of children from annulled marriage 26. Marriage of convenience 27. Grounds for divorce Translation: Union of Cyprus Municipalities Law:104(I)/2003 The Marriage Law of 2003 is issued by publication in the Official Gazette of the Republic of Cyprus under Section 52 of the Constitution ______ Number 104(I) of 2003 THE MARRIAGE LAW The House of Representatives decides as follows: PART I – PRELIMINARY This Law may be cited as the Marriage Law of 2003 Short Title 1. In this Law unless the context otherwise requires – Interpretation 2.