Birds of the Indonesian Archipelago: Greater Sundas and Wallacea James A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Species Limits in Some Philippine Birds Including the Greater Flameback Chrysocolaptes Lucidus

FORKTAIL 27 (2011): 29–38 Species limits in some Philippine birds including the Greater Flameback Chrysocolaptes lucidus N. J. COLLAR Philippine bird taxonomy is relatively conservative and in need of re-examination. A number of well-marked subspecies were selected and subjected to a simple system of scoring (Tobias et al. 2010 Ibis 152: 724–746) that grades morphological and vocal differences between allopatric taxa (exceptional character 4, major 3, medium 2, minor 1; minimum score 7 for species status). This results in the recognition or confirmation of species status for (inverted commas where a new English name is proposed) ‘Philippine Collared Dove’ Streptopelia (bitorquatus) dusumieri, ‘Philippine Green Pigeon’ Treron (pompadora) axillaris and ‘Buru Green Pigeon’ T. (p.) aromatica, Luzon Racquet-tail Prioniturus montanus, Mindanao Racquet-tail P. waterstradti, Blue-winged Raquet-tail P. verticalis, Blue-headed Raquet-tail P. platenae, Yellow-breasted Racquet-tail P. flavicans, White-throated Kingfisher Halcyon (smyrnensis) gularis (with White-breasted Kingfisher applying to H. smyrnensis), ‘Northern Silvery Kingfisher’ Alcedo (argentata) flumenicola, ‘Rufous-crowned Bee-eater’ Merops (viridis) americanus, ‘Spot-throated Flameback’ Dinopium (javense) everetti, ‘Luzon Flameback’ Chrysocolaptes (lucidus) haematribon, ‘Buff-spotted Flameback’ C. (l.) lucidus, ‘Yellow-faced Flameback’ C. (l.) xanthocephalus, ‘Red-headed Flameback’ C. (l.) erythrocephalus, ‘Javan Flameback’ C. (l.) strictus, Greater Flameback C. (l.) guttacristatus, ‘Sri Lankan Flameback’ (Crimson-backed Flameback) Chrysocolaptes (l.) stricklandi, ‘Southern Sooty Woodpecker’ Mulleripicus (funebris) fuliginosus, Visayan Wattled Broadbill Eurylaimus (steerii) samarensis, White-lored Oriole Oriolus (steerii) albiloris, Tablas Drongo Dicrurus (hottentottus) menagei, Grand or Long-billed Rhabdornis Rhabdornis (inornatus) grandis, ‘Visayan Rhabdornis’ Rhabdornis (i.) rabori, and ‘Visayan Shama’ Copsychus (luzoniensis) superciliaris. -

Traffic.Org/Home/2015/12/4/ Thousands-Of-Birds-Seized-From-East-Java-Port.Html

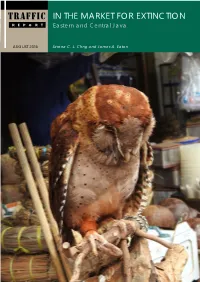

TRAFFIC IN THE MARKET FOR EXTINCTION REPORT Eastern and Central Java AUGUST 2016 Serene C. L. Chng and James A. Eaton TRAFFIC Report: In The Market for Extinction: Eastern and Central Java 1 TRAFFIC REPORT TRAFFIC, the wild life trade monitoring net work, is the leading non-governmental organization working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. TRAFFIC is a strategic alliance of WWF and IUCN. Reprod uction of material appearing in this report requires written permission from the publisher. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations con cern ing the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views of the authors expressed in this publication are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect those of TRAFFIC, WWF or IUCN. Published by TRAFFIC. Southeast Asia Regional Office Unit 3-2, 1st Floor, Jalan SS23/11 Taman SEA, 47400 Petaling Jaya Selangor, Malaysia Telephone : (603) 7880 3940 Fax : (603) 7882 0171 Copyright of material published in this report is vested in TRAFFIC. © TRAFFIC 2016. ISBN no: 978-983-3393-50-3 UK Registered Charity No. 1076722. Suggested citation: Chng, S.C.L. and Eaton, J.A. (2016). In the Market for Extinction: Eastern and Central Java. TRAFFIC. Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia. Front cover photograph: An Oriental Bay Owl Phodilus badius displayed for sale at Malang Bird Market Credit: Heru Cahyono/TRAFFIC IN THE MARKET FOR EXTINCTION Eastern and Central Java Serene C. -

Indonesien 03

Indonesien 03. bis 24.09.2017 von Klaus Handke Örtliche Guides: Yudi (Bali), Hery und Sam (Flores), Heri (Sumatra), Hardy/Iskander (Java) Fahrer: Santos (Bali), Ismet (Ende/Flores), Marcelo (Labuan Bajo/Flores), Yus (Java) Teilnehmer: Pia und Klaus Handke 2 Vorwort Unsere zweite Indonesienreise mit Besuch der Inseln Bali, Flores, Sumatra und Java war sehr erlebnisreich und interessant, aber auch anstrengend. Viele Transfers, lange Staus, frühes Aufstehen und die Mentalität vieler Indonesier erforderten zeitweise gute Kondition und Nerven. Der Wechsel vieler Guides (auf unserer Reise alleine fünf ornithologische Führer) mit teilweise sehr unterschiedlicher Kenntnis, Ausrüstung und engl. Sprachvermögen war nicht immer einfach. Dennoch hat diese Reise mit knapp 330 Vogelarten, davon 110 neu, unsere Erwartungen erfüllt. Wir haben zumindest einen kleinen Eindruck von der Vielfalt des Landes bekommen. Um das Land besser kennenzulernen, sind sicher weitere Reisen nach Sulawesi, auf die kleinen Sundainseln und nach Sumatra erforderlich. Ein besonderes Erlebnis war es mit dem Besuch von Flores, die Wallace-Linie zu überqueren. Fauna und Flora unterscheiden sich auf beiden Seiten der Linie sehr stark. So fehlen östlich der Linie Breitrachen, Bülbüls, Blattvögel und Timalien. Dafür gibt es hier Honiganzeiger und Dickköpfe und Brillenvögel; Kuckuckswürger und Monarchen sind viel häufiger. Der Reisetermin im September war gut gewählt. Touristisch ist um diese Zeit Nebensaison, das Wetter war sehr angenehm (trocken und kein Regentag) und es gab sehr wenig Blutegel und Mücken. Die Unterschiede zwischen den einzelnen Inseln sind enorm, z.B. zwischen dem paradiesischen hinduistisch geprägten Bali und dem extrem dicht besiedelten moslemischen Java. Dass dieses Land mit seiner Vielfalt an Religionen und Völkern nicht auseinandergefallen ist, grenzt an ein Wunder. -

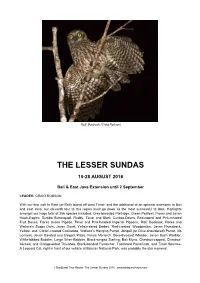

The Lesser Sundas

‘Roti’ Boobook (Craig Robson) THE LESSER SUNDAS 10-28 AUGUST 2016 Bali & East Java Extension until 2 September LEADER: CRAIG ROBSON With our first visit to Rote (or Roti) Island off west Timor, and the additional of an optional extension to Bali and east Java, our eleventh tour to this region must go down as the most successful to date. Highlights amongst our huge total of 356 species included: Grey-breasted Partridge, Green Peafowl, Flores and Javan Hawk-Eagles, Sumba Buttonquail, Ruddy, Timor and Black Cuckoo-Doves, Red-naped and Pink-headed Fruit Doves, Flores Green Pigeon, Timor and Pink-headed Imperial Pigeons, ‘Roti’ Boobook, Flores and Wallace's Scops Owls, Javan Owlet, Yellow-eared Barbet, ‘Red-crested’ Woodpecker, Javan Flameback, Yellow- and ‘Citron’-crested Cockatoos, Wallace’s Hanging Parrot, Jonquil (or Olive-shouldered) Parrot, Iris Lorikeet, Javan Banded and Elegant Pittas, Flores Monarch, Bare-throated Whistler, Javan Bush Warbler, White-bibbed Babbler, Large Wren-Babbler, Black-winged Starling, Bali Myna, Chestnut-capped, Chestnut- backed, and Orange-sided Thrushes, Black-banded Flycatcher, Tricolored Parrotfinch, and Timor Sparrow. A Leopard Cat, right in front of our vehicle at Baluran National Park, was probably the star mammal. ! ! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: The Lesser Sundas 2016 www.birdquest-tours.com We all assembled at the Airport in Denpasar, Bali and checked-in for our relatively short flight to Waingapu, the main town on the island of Sumba. On arrival we were whisked away to our newly built hotel, and arrived just in time for lunch. By the early afternoon we were already beginning our explorations with a visit to the coastline north-west of town in the Londa Liru Beach area. -

Picidae Species Tree

Picidae: Woodpeckers Eurasian Wryneck, Jynx torquilla Jynginae Red-throated Wryneck, Jynx ruficollis Speckled Piculet, Vivia innominata ?Tawny Piculet, Picumnus fulvescens ?Ochraceous Piculet, Picumnus limae Mottled Piculet, Picumnus nebulosus Picumninae Varzea Piculet, Picumnus varzeae Spotted Piculet, Picumnus pygmaeus White-bellied Piculet, Picumnus spilogaster Arrowhead Piculet, Picumnus minutissimus Ochre-collared Piculet, Picumnus temminckii Speckle-chested Piculet, Picumnus steindachneri White-wedged Piculet, Picumnus albosquamatus Ocellated Piculet, Picumnus dorbignyanus White-barred Piculet, Picumnus cirratus Plain-breasted Piculet, Picumnus castelnau Fine-barred Piculet, Picumnus subtilis Rufous-breasted Piculet, Picumnus rufiventris Scaled Piculet, Picumnus squamulatus Golden-spangled Piculet, Picumnus exilis Lafresnaye’s Piculet, Picumnus lafresnayi Orinoco Piculet, Picumnus pumilus Bar-breasted Piculet, Picumnus aurifrons ?Rusty-necked Piculet, Picumnus fuscus Ecuadorian Piculet, Picumnus sclateri Olivaceous Piculet, Picumnus olivaceus ?Grayish Piculet, Picumnus granadensis Chestnut Piculet, Picumnus cinnamomeus African Piculet, Verreauxia africana Rufous Piculet, Sasia abnormis Sasiinae White-browed Piculet, Sasia ochracea Antillean Piculet, Nesoctites micromegas NESOCTITINI Heart-spotted Woodpecker, Hemicircus canente HEMICIRCINI Gray-and-buffWoodpecker, Hemicircus concretus Bay Woodpecker, Blythipicus pyrrhotis Maroon Woodpecker, Blythipicus rubiginosus Orange-backed Woodpecker, Reinwardtipicus validus CHRYSOCOLAPTINI Picinae -

Ethnoornithology: Identification of Bird Names Mentioned in Kakawin Rāmāyana, a 9Th-Century Javanese Poem (Java, Indonesia)

BIODIVERSITAS ISSN: 1412-033X Volume 20, Number 11, November 2019 E-ISSN: 2085-4722 Pages: 3213-3222 DOI: 10.13057/biodiv/d201114 Ethnoornithology: Identification of bird names mentioned in Kakawin Rāmāyana, a 9th-century Javanese poem (Java, Indonesia) DEDE MULYANTO1, JOHAN ISKANDAR2, RIMBO GUNAWAN1, RUHYAT PARTASASMITA2,♥ 1Anthropology Graduate Programs, Faculty of Social and Political Science, Universitas Padjadjaran. Jl. Raya Bandung-Sumedang Km 21, Jatinangor, Sumedang 45363, West Java, Indonesia 2Department of Biology, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Universitas Padjadjaran. Jl. Raya Bandung-Sumedang Km 21, Jatinangor, Sumedang 45363, West Java, Indonesia. Tel.: +62-22-7796412 ext. 104, Fax.: +62-22-7794545. email: [email protected]; [email protected] Manuscript received: 12 September 2019. Revision accepted: 17 October 2019. Abstract. Mulyanto D, Iskandar J, Gunawan R, Partasasmita R. 2019. Ethnoornithology: Identification of bird names mentioned in Kakawin Rāmāyana, a 9th-century Javanese poem (Java, Indonesia). Biodiversitas 20: 3213-3222. Birds have played an important role in Javanese culture for a long time. For example, birds have been culturally used as sources of folk stories, myths, illustrated old manuscripts, paintings on relief walls of temples, and inspiration of writers to make poems. This article presents the results of an ethnoornithology study that tried to identify all bird names mentioned in Kakawin Rāmāyana (KR), an old Javanese poem, using a qualitative method, mainly interpreting KR text based on an ethnoornithological approach. The results showed that 84 bird names are mentioned in the Kakawin Rāmāyana, belonging to 26 families, and 17 orders. The birds mentioned in KR are predominantly residents, some are regular visitors or vagrant, and only a few are absent. -

Indonesia Bali Birding Extension 16Th July to 22Nd July 2021 (7 Days)

Indonesia Bali Birding Extension 16th July to 22nd July 2021 (7 days) Bali Starling by Dubi Shapiro The magical island of Bali forms part of the chain of tropical islands in the Indonesian archipelago and, although it’s most famous as a beach tourism Mecca, Bali has a lot to offer the birder and naturalist. Situated at the eastern end of the Greater Sundas, Bali provides superb birding and wildlife viewing. The island’s most iconic bird, the beautiful and very rare Bali Myna or Bali Starling, will be top of the hit list during our Bali birding extension. Most of our time will be spent at the world- renowned Bali Barat National Park. Here we will search for some of the last few wild Bali Mynas in existence, and we will also be treated to numerous other avian treasures, many of which are only shared with neighbouring Java. These include the endangered Black-winged Starling, Beach Stone- curlew, the dazzling Cerulean Kingfisher, Green Junglefowl, Javan Plover, Java Sparrow and the spectacular Javan Banded Pitta! Our trip also ventures into the highlands where specialities include Crescent-chested Babbler, Javan Whistling and Sunda Thrushes, Yellow-throated Hanging Parrot, the delightful Sunda Warbler, Blood-breasted Flowerpecker and Grey-throated Ibon. The Bali countryside is eye-catching and we RBL Indonesia – Bali Itinerary 2 will additionally find ourselves enjoying such wonderful and range-restricted species as White- capped and Javan Munias, the stunning Javan Kingfisher and Cinnamon Bittern while gazing across emerald-green rice paddies, uniquely punctuated with Hindu temples and soaking in the island’s incredible beauty. -

Avian Biogeography and Conservation in Eastern Indonesia John C

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2014 Avian Biogeography and Conservation in Eastern Indonesia John C. Mittermeier Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Recommended Citation Mittermeier, John C., "Avian Biogeography and Conservation in Eastern Indonesia" (2014). LSU Master's Theses. 2367. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2367 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AVIAN BIOGEOGRAPHY AND CONSERVATION IN EASTERN INDONESIA A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in The Department of Biological Sciences by John C. Mittermeier B.A., Yale University, 2008 MSc, University of Oxford, 2011 December 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I have been fortunate to receive incredible support and encouragement from many friends and colleagues during my time in Baton Rouge and throughout my fieldwork in Indonesia. I am very grateful for this, and look forward to continuing the many friendships and collaborations that I have developed at LSU. First and foremost, I would especially like to thank my advisor Dr Robb Brumfield, who provided fantastic mentorship and guidance during my thesis. My committee members Drs Fred Sheldon, J.V. Remsen, and Phil Stouffer also deserve special thanks for their advice, feedback on drafts and grant submissions, and help in working through ideas and research plans. -

Biotropika: Journal of Tropical Biology | Vol

E-ISSN 2549-8703 I P-ISSN 2302-7282 BIOTROPIKA Journal of Tropical Biology https://biotropika.ub.ac.id/ Vol. 9 | No. 1 | 2021 | DOI: 10.21776/ub.biotropika.2021.009.01.04 BUFFER ZONE MANAGEMENT IMPACT ON BIRDS ASSEMBLAGE IN THE HIGH NATURE VALUE FARMLAND (HNVf): A STUDY CASE ON MERU BETIRI NATIONAL PARK DAMPAK PENGELOLAAN ZONA PENYANGGA PADA SUSUNAN BURUNG- BURUNG DI HIGH NATURE VALUE FARMLAND (HNVf): SEBUAH STUDI KASUS PADA TAMAN NASIONAL MERU BETIRI Nilasari Dewi1), Agung Sih Kurnianto1)* Received : March 9th, 2021 ABSTRACT This study aims to analyze the distribution of bird communities and the impact of Accepted : April 10th, 2021 vegetation on bird habitat preferences in the buffer zone. Research is carried out in agricultural areas in the Buffer zone, Rehabilitation Zone, and on the edge of the plantation. The research location was determined at 37 points: Rajekwesi (4), Sukamade (12), Bandealit (8), Wonoasri (5), Andongrejo (3), Sanenrejo (5). We applied the point count method (r = 17.5 m) in this study, where each point is at Author Affiliation: least 100-150 meters apart. In the study, 74.6% of records were birds with agricultural specialities and 71.30% of individuals on tree habitats. Birds with 1) Agrotechnology Study Program, specialization in agriculture were found in large numbers related to the Agriculture Faculty, University of protection provided by the TNMB conservation area to bird habitat. Sukamade is Jember, Kalimantan street no. 37, the area with the highest number of records. As many as 40.10% were found in Jember, East Java Province, tree habitats followed by seedling (16.28%), poles (15.93%), flying over Indonesia (15.76%), and sapling (11.90%). -

Digital Repository Universitas Jember Digital Repository Universitas Jember

DigitalDigital RepositoryERepository-ISSN 2549-8703 UniversitasIUniversitas P-ISSN 2302-7282 Jember Jember BIOTROPIKA Journal of Tropical Biology https://biotropika.ub.ac.id/ Vol. 9 | No. 1 | 2021 | DOI: 10.21776/ub.biotropika.2021.009.01.04 BUFFER ZONE MANAGEMENT IMPACT ON BIRDS ASSEMBLAGE IN THE HIGH NATURE VALUE FARMLAND (HNVf): A STUDY CASE ON MERU BETIRI NATIONAL PARK DAMPAK PENGELOLAAN ZONA PENYANGGA PADA SUSUNAN BURUNG- BURUNG DI HIGH NATURE VALUE FARMLAND (HNVf): SEBUAH STUDI KASUS PADA TAMAN NASIONAL MERU BETIRI Nilasari Dewi1), Agung Sih Kurnianto1)* Received : March 9th, 2021 ABSTRACT This study aims to analyze the distribution of bird communities and the impact of Accepted : April 10th, 2021 vegetation on bird habitat preferences in the buffer zone. Research is carried out in agricultural areas in the Buffer zone, Rehabilitation Zone, and on the edge of the plantation. The research location was determined at 37 points: Rajekwesi (4), Sukamade (12), Bandealit (8), Wonoasri (5), Andongrejo (3), Sanenrejo (5). We applied the point count method (r = 17.5 m) in this study, where each point is at Author Affiliation: least 100-150 meters apart. In the study, 74.6% of records were birds with agricultural specialities and 71.30% of individuals on tree habitats. Birds with 1) Agrotechnology Study Program, specialization in agriculture were found in large numbers related to the Agriculture Faculty, University of protection provided by the TNMB conservation area to bird habitat. Sukamade is Jember, Kalimantan street no. 37, the area with the highest number of records. As many as 40.10% were found in Jember, East Java Province, tree habitats followed by seedling (16.28%), poles (15.93%), flying over Indonesia (15.76%), and sapling (11.90%). -

Indonesia Bali Birding Extension 14Th to 20Th July 2020 (7 Days)

Indonesia Bali Birding Extension 14th to 20th July 2020 (7 days) Bali Myna by Adam Riley The magical island of Bali forms part of the chain of tropical islands in the Indonesian archipelago and, although it’s most famous as a beach tourism Mecca, Bali has a lot to offer the birder and naturalist. Situated at the eastern end of the Greater Sundas, Bali provides superb birding and wildlife viewing. The island’s most iconic bird, the beautiful and very rare Bali Myna or Bali Starling, will be top of the hit list during our Bali birding extension. Most of our time will be spent at the world- renowned Bali Barat National Park. Here we will search for some of the last few wild Bali Mynas in existence, and we will also be treated to numerous other avian treasures, many of which are only shared with neighbouring Java. These include the endangered Black-winged Starling, Beach Stone- curlew, the dazzling Cerulean Kingfisher, Green Junglefowl, Javan Plover, Java Sparrow and the spectacular Javan Banded Pitta! RBL Indonesia – Bali Itinerary 2 Our trip also ventures into the highlands where specialities include Crescent-chested Babbler, Javan Whistling and Sunda Thrushes, Yellow-throated Hanging Parrot, the delightful Sunda Warbler, Blood-breasted Flowerpecker and Grey-throated Ibon. The Bali countryside is eye-catching and we will additionally find ourselves enjoying such wonderful and range-restricted species as White- capped and Javan Munias, the stunning Javan Kingfisher and Cinnamon Bittern while gazing across emerald-green rice paddies, uniquely punctuated with Hindu temples and soaking in the island’s incredible beauty. -

1996 IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals

The tUCN Species Survival Commission 1996 lUCN Red List of Threatened Animals Compiled and Edited by Jonathan Baillie and Brian Groombridge The Worid Conseivation Union 9 © 1996 International Union for Conservation ot Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational and otfier non-commercial purposes is authorized without permission from the copyright holder, provided the source is cited and the copyright holder receives a copy of the reproduced material. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of lUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Citation: lUCN 1996. 1996 lUCN Red List of Threatened Animals. lUCN, Gland, Switzerland. ISBN 2-8317-0335-2 Co-published by lUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge U.K., and Conservation International, Washington, D.C., U.S.A. Available from: lUGN Publications Services Unit, 219c Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CBS ODL, United Kingdom. Tel: + 44 1223 277894; Fax: + 44 1223 277175; E-mail: [email protected]. A catalogue of all lUCN publications can be obtained from the same address. Camera-ready copy of the introductory text by the Chicago Zoological Society, Brookfield, Illinois 60513, U.S.A. Camera-ready copy of the data tables, lists, and index by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre, 21 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge CB3 ODL, U.K.