Selection of Quranic Verses Referencing Time in Different Contexts on Duration of Creation Truly Your Lord Is God, Who Created T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perspectives Behind Translating House of Flesh by Yusuf Idris

C. Lindley Cross 12 June 2009 Perspectives Behind Translating House of Flesh by Yusuf Idris Within the canon of great minds and talents that brought Egypt to a literary renaissance between 1880 and 1960, Yusuf Idris (1927-1991) is widely acknowledged as the master of the Egyptian short story. Employing a compact, terse style, charged with an energy that viscerally engages the senses as much as it does the imagination and intellect, he burst into the public eye with a prolific outpouring of work in the years directly following the 1952 Revolution. His stories from the beginning were confrontational and provocative, articulated from his firm commitment to political activism. Although his literary efforts had largely petered out by the 1970s, the uncompromising zeal and intensity he brought to his short stories left a groundbreaking impression on the history of modern Arabic fiction. Inside the Arabic literary tradition, the short story (al-qiṣṣah al-qaṣīrah, or al-uqṣuṣah) is in itself a genre that bears a political dimension, first and foremost due to its having been largely inspired by foreign models.1 Even in Europe and North America, it only achieved widespread acceptance as a literary form distinct from novels in the early nineteenth century. In the climate of French literary prestige and British colonialism encroaching upon Egypt’s identity, the choice whether to adopt or reject such forms was often indicative of a wider political view. Some intellectuals were convinced that the only way to save Egypt from cultural effacement was to re-appropriate the language and forms of the great classical masters like Abu Nawas and al- Mutanabbi and inject them into contemporary literature, warding off further corruption as a vaccine wards off disease. -

Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam

Institute of Asian and African Studies at The Hebrew University The Max Schloessinger Memorial Foundation REPRINT FROM JERUSALEM STUDIES IN ARABIC AND ISLAM I 1979 THE MAGNES PRESS. THE HEBREW UNIVERSITY. JERUSALEM PROPHETS AND PROGENITORS IN THE EARLY SHI'ATRADITION* Uri Rubin INTRODUCTION As is well known, the Shi 'I belief that 'Ali' should have been Muhammad's succes- sor was based on the principle of hereditary Califate, or rather Imamate. 'Ali's father, Abu Talib, and Muhammad's father, 'Abdallah, were brothers, so that Muhammad and 'Ali were first cousins. Since the Prophet himself left no sons, the Shi 'a regarded' All as his only rightful successor.' Several Shi 'I traditions proclaim 'All's family relationship (qariiba) to Muhammad as the basis for his hereditary rights. For the sake of brevity we shall only point out some of the earliest.A number of these early Shi T traditions center around the "brothering", i.e. the mu'akhiih which took place after the hijra; this was an agreement by which each emigrant was paired with one of the Ansar and the two, who thus became brothers, were supposed to inherit each other (see Qur'an, IV, 33? 'All, as an exception, was paired not with one of the Ansar but with the Prophet himself." A certain verse in the Qur'an (VIII, 72) was interpreted as stating that the practice of mu iikhiin was confined only to the Muhajinin and the Ansar, to the exclusion of those believers who had stayed back in Mecca after the hijra. They re- tained the old practice of inheritance according to blood-relationship." This prac- tice, which was introduced in al-Madi na, affected the hereditary rights of the families of the Muhajiriin who were supposed to leave their legacy to their Ansari * This article is a revised form of a chapter from my thesis on some aspects of Muhammad's prophethood in the early literature of hadt th. -

Prophets of the Quran: an Introduction (Part 1 of 2)

Prophets of the Quran: An Introduction (part 1 of 2) Description: Belief in the prophets of God is a central part of Muslim faith. Part 1 will introduce all the prophets before Prophet Muhammad, may the mercy and blessings of God be upon him, mentioned in the Muslim scripture from Adam to Abraham and his two sons. By Imam Mufti (© 2013 IslamReligion.com) Published on 22 Apr 2013 - Last modified on 25 Jun 2019 Category: Articles >Beliefs of Islam > Stories of the Prophets The Quran mentions twenty five prophets, most of whom are mentioned in the Bible as well. Who were these prophets? Where did they live? Who were they sent to? What are their names in the Quran and the Bible? And what are some of the miracles they performed? We will answer these simple questions. Before we begin, we must understand two matters: a. In Arabic two different words are used, Nabi and Rasool. A Nabi is a prophet and a Rasool is a messenger or an apostle. The two words are close in meaning for our purpose. b. There are four men mentioned in the Quran about whom Muslim scholars are uncertain whether they were prophets or not: Dhul-Qarnain (18:83), Luqman (Chapter 31), Uzair (9:30), and Tubba (44:37, 50:14). 1. Aadam or Adam is the first prophet in Islam. He is also the first human being according to traditional Islamic belief. Adam is mentioned in 25 verses and 25 times in the Quran. God created Adam with His hands and created his wife, Hawwa or Eve from Adam’s rib. -

Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: a Critical Evaluation of Two Translations

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.8, No.2, 2017 Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: A Critical Evaluation of Two Translations Izzeddin M. I. Issa Dept. of English & Translation, Jadara University, PO box 733, Irbid, Jordan Abstract This study is devoted to discuss the renditions of the prophets' names in the Holy Quran due to the authority of the religious text where they reappear, the significance of the figures who carry them, the fact that they exist in many languages, and the fact that the Holy Quran addresses all mankind. The data are drawn from two translations of the Holy Quran by Ali (1964), and Al-Hilali and Khan (1993). It examines the renditions of the twenty five prophets' names with reference to translation strategies in this respect, showing that Ali confused the conveyance of six names whereas Al-Hilali and Khan confused the conveyance of four names. Discussion has been raised thereupon to present the correct rendition according to English dictionaries and encyclopedias in addition to versions of the Bible which add a historical perspective to the study. Keywords: Mistranslation, Prophets, Religious, Al-Hilali, Khan. 1. Introduction In Prophets’ names comprise a significant part of people's names which in turn constitutes a main subdivision of proper nouns which include in addition to people's names the names of countries, places, months, days, holidays etc. In terms of translation, many translators opt for transliterating proper names thinking that transliteration is a straightforward process depending on an idea deeply rooted in many people's minds that proper nouns are never translated or that the translation of proper names is as Vermes (2003:17) states "a simple automatic process of transference from one language to another." However, in the real world the issue is different viz. -

Pauri 5 Overview the Fifth Pauri Is Accompanied by Two Saloks. The

The Guru Granth Sahib Project Asa Ki Var, Version 1 Pauri 5 Overview The fifth pauri is accompanied by two saloks. The first salok is comprised of four lines and the second is comprised of twenty-six. In the first salok, there is a description of the Divine-play (rās) in creation. It is suggested that nature itself is performing a Divine-play in which, parts of time and elements of nature are characters. The second salok contains three parts. The first part constitutes a satirical narrative of a theatrical performance (rās līlā1) - being carried out by actors, performers or street-artists. It explains that instead of making human life worthy through gaining an understanding of the mystery of the play of nature, human life is being wasted by engaging in superficial plays. The second part mentions the life- sketch of IkOankar’s servants imbued with IkOankar. In the third part, there is a satire on dance-rotations of the street-artists being compared to the devices rotating on their axis. In the pauri, it has been mentioned that the Nam of the formless IkOankar, when remembered in the spirit of complete surrender, is the right course of action to attain spiritual freedom. salok m: 1. ghaṛīā sabhe gopīā pahar kann̖ gopāl. gahaṇe paüṇu pāṇī baisantaru candu sūraju avtār. saglī dhartī mālu dhanu vartaṇi sarab jañjālu. nānak musai giān vihūṇī khāi gaïā jamkālu.1. Literal Translation 1 Literally, a play (līlā) of aesthetics (rās), or more broadly, a pleasurable act or dance of love performed by Krishan and the cow-maidens, his beloved friends. -

European Bulletin of Himalayan Research 27: 67-125 (2004)

Realities and Images of Nepal’s Maoists after the Attack on Beni1 Kiyoko Ogura 1. The background to Maoist military attacks on district head- quarters “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun” – Mao Tse-Tung’s slogan grabs the reader’s attention at the top of its website.2 As the slogan indicates, the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) has been giving priority to strengthening and expanding its armed front since they started the People’s War on 13 February 1996. When they launched the People’s War by attacking some police posts in remote areas, they held only home-made guns and khukuris in their hands. Today they are equipped with more modern weapons such as AK-47s, 81-mm mortars, and LMGs (Light Machine Guns) purchased from abroad or looted from the security forces. The Maoists now are not merely strengthening their military actions, such as ambushing and raiding the security forces, but also murdering their political “enemies” and abducting civilians, using their guns to force them to participate in their political programmes. 1.1. The initial stages of the People’s War The Maoists developed their army step by step from 1996. The following paragraph outlines how they developed their army during the initial period of three years on the basis of an interview with a Central Committee member of the CPN (Maoist), who was in charge of Rolpa, Rukum, and Jajarkot districts (the Maoists’ base area since the beginning). It was given to Li Onesto, an American journalist from the Revolutionary Worker, in 1999 (Onesto 1999b). -

Literature and the Arts of Northwest Colorado Volume 3, Issue 3, 2011

Literature and the Arts of Northwest Colorado Volume 3, Issue 3, 2011 Colorado Northwestern Community College Literature and the Arts of Northwest Colorado Volume 3, Issue 3, 2011 EDITOR ART EDITOR PRODUCTION/DESIGN Joe Wiley Elizabeth Robinson Denise Wade EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Ally Palmer Jinnah Schrock Rose Peterson Mary Slack Ariel Sanchez Michael Willie ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The staff of Waving Hands Review thanks the following people: -CNCC President Russell George, his cabinet, the RJCD Board of Trustees, the MCAJCD Board of Control, and the CNCC Marketing Department for continued funding and support -All those who submitted work -All those who encouraged submissions Waving Hands Review, the literature and arts magazine of Colorado Northwestern Community College, seeks to publish exemplary works by emerging and established writers and artists of Northwest Colorado. Submissions in poetry, fiction, non-fiction, drama, photography, and art remain anonymous until a quality-based selection is made. Unsolicited submissions are welcome between September 1 and March 1. We accept online submissions only. Please visit the Waving Hands Review website at www.cncc.edu/waving_hands/ for detailed submission guidelines, or go to the CNCC homepage and click on the Waving Hands Review logo. Waving Hands Review is staffed by students of Creative Writing II. All works Copyright 2011 by individual authors and artists. Volume 3, Issue 3, 2011 Table of Contents Artwork Yuri Chicovsky Cover Self-Portrait Janele Husband 17 Blanketed Deer Peter Bergmann 18 Winter -

EARLY BENGALI PROSE CAREY to Vibyasxg-ER by Thesi S Submit

EARLY BENGALI PROSE CAREY TO VIBYASXg-ER By Sisirlcumar Baa Thesi s submit ted for the Ph.D. degree in the University of London* June 1963 ProQuest Number: 10731585 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731585 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract Acknowledgment Transliteration Abbreviations; Chapter I. Introduction 1-32 Chapter II. The beginnings of Bengali prose 33-76 Chapter III. William Carey 77-110 Chapter IV. Ramram Basu 110-154 Chapter V. M?ityun;ja^ Bidyalaqikar 154-186 Chapter VI. Rammohan Ray 189-242 Chapter VII. Early Newspapers (1818-1830) 243-268 Chapter VUI.Sarpbad Prabhakar: Ii^varcandra Gupta 269-277 Chapter IX. Tattvabodhi#! Patrika 278-320 Chapter X. Vidyasagar 321-367 Bibli ography 36 8-377 —oOo** ABSTRACT The present thesis examines the growth of Bengali prose from its experimental Beginnings with Carey to its growth into full literary stature in the hands of Vidyasagar. The subject is presented chronologically and covers roughly the first half of the 1 9 th century. -

Stories of the Prophets

Stories of the Prophets Written by Al-Imam ibn Kathir Translated by Muhammad Mustapha Geme’ah, Al-Azhar Stories of the Prophets Al-Imam ibn Kathir Contents 1. Prophet Adam 2. Prophet Idris (Enoch) 3. Prophet Nuh (Noah) 4. Prophet Hud 5. Prophet Salih 6. Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) 7. Prophet Isma'il (Ishmael) 8. Prophet Ishaq (Isaac) 9. Prophet Yaqub (Jacob) 10. Prophet Lot (Lot) 11. Prophet Shuaib 12. Prophet Yusuf (Joseph) 13. Prophet Ayoub (Job) 14 . Prophet Dhul-Kifl 15. Prophet Yunus (Jonah) 16. Prophet Musa (Moses) & Harun (Aaron) 17. Prophet Hizqeel (Ezekiel) 18. Prophet Elyas (Elisha) 19. Prophet Shammil (Samuel) 20. Prophet Dawud (David) 21. Prophet Sulaiman (Soloman) 22. Prophet Shia (Isaiah) 23. Prophet Aramaya (Jeremiah) 24. Prophet Daniel 25. Prophet Uzair (Ezra) 26. Prophet Zakariyah (Zechariah) 27. Prophet Yahya (John) 28. Prophet Isa (Jesus) 29. Prophet Muhammad Prophet Adam Informing the Angels About Adam Allah the Almighty revealed: "Remember when your Lord said to the angels: 'Verily, I am going to place mankind generations after generations on earth.' They said: 'Will You place therein those who will make mischief therein and shed blood, while we glorify You with praises and thanks (exalted be You above all that they associate with You as partners) and sanctify You.' Allah said: 'I know that which you do not know.' Allah taught Adam all the names of everything, then He showed them to the angels and said: "Tell Me the names of these if you are truthful." They (angels) said: "Glory be to You, we have no knowledge except what You have taught us. -

The History of India : As Told by Its Own Historians. the Muhammadan Period

wmmmimmB::::::: President White Library, Cornell UNivER'SfTY. f\,^»m^^ »ff^t CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 3 1924 073 036 786 The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924073036786 THE HISTORY OF INDIA. THE HISTORY OF INDIA, BY ITS OWS HISTORIAl^S. THE MUHAMMADAN PERIOD. THE POSTHUMOUS PAPEES OF THE LATE SIR H. M. ELLIOT, K.O.B.. EDITED AND CONTINUED BY PEOFESSOE JOHN D0W80N, M.E.A.S., STAFF COLLEGE, SAMDHXJRST. YOL, YIII. LONDON: TEiJBJSTEE AND CO., 57 and 59, LUDGATE HILL. 1877. [_All rights reserved.l 'H /\. I O'^Tt"^ STEPHEN AUSTIN AND SONS, PRINTERS, HERTFORD. PREFACE. Eleven years have elapsed since the materials collected by Sir BE. M. Elliot for this work were first placed in my hands for revision and publication. In bulk the papers seemed sufficient and more than sufficient for the projected work, and it was thought that an Editor would have little to do beyond selecting extracts for publication and revising the press. "With this belief I undertook the work, and it was announced as preparing for publication under my care. When the papers came into my possession, and the work of selection was entered upon, I soon found that the MSS., so far from being superabundant, were very deficient, and that for some of the most important reigns, as those of Akbar and Aurangzeb, no provision had been made. The work had been long advertised, and had received the support of the Secretary of State for India, not as a series of Selections from the Papers of Sir H. -

Darfur: Extra Judicial Execution of 168 Men

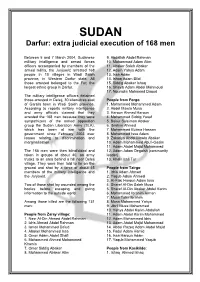

SUDAN Darfur: extra judicial execution of 168 men Between 5 and 7 March 2004, Sudanese 9. Abdallah Abdel Rahman military intelligence and armed forces 10. Mohammed Adam Atim officers accompanied by members of the 11. Abaker Saleh Abaker armed militia, the Janjawid, arrested 168 12. Adam Yahya Adam people in 10 villages in Wadi Saleh 13. Issa Adam province, in Western Darfur state. All 14. Ishaq Adam Bilal those arrested belonged to the Fur, the 15. Siddig Abaker Ishaq largest ethnic group in Darfur. 16. Shayib Adam Abdel Mahmoud 17. Nouradin Mohamed Daoud The military intelligence officers detained those arrested in Deleij, 30 kilometres east People from Forgo of Garsila town in Wadi Saleh province. 1. Mohammed Mohammed Adam According to reports military intelligence 2. Abdel Mawla Musa and army officials claimed that they 3. Haroun Ahmed Haroun arrested the 168 men because they were 4. Mohammed Siddig Yusuf sympathizers of the armed opposition 5. Bakur Suleiman Abaker group the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA), 6. Ibrahim Ahmed which has been at war with the 7. Mohammed Burma Hassan government since February 2003 over 8. Mohammed Issa Adam issues relating to discrimination and 9. Zakariya Abdel Mawla Abaker marginalisation. 10. Adam Mohammed Abu’l-Gasim 11. Adam Abdel Majid Mohammed The 168 men were then blindfolded and 12. Adam Adam Degaish (community taken in groups of about 40, on army leader) trucks to an area behind a hill near Deleij 13. Khalil Issa Tur village. They were then told to lie on the ground and shot by a force of about 45 People from Tairgo members of the military intelligence and 1. -

25 Prophets of Islam

Like 5.2k Search Qul . Home Prayer Times Ask Qul TV The Holy Qur'an Library Video Library Audio Library Islamic Occasions About Pearl of Wisdom Library » Our Messengers » 25 Prophets of Islam with regards to Allah's verse in the 25 Prophets of Islam Qur'an: "Indeed Allah desires to repel all impurity from you... 25 Prophets of Islam said,?'Impunity IS doubt, and by Allah, we never doubt in our Lord. How many prophets did God send to mankind? This is a debated issue, but what we know is what God has told us in the Quran. God says he sent a prophet to every nation. He says: Imam Ja'far ibn Muhammad al-Sadiq “For We assuredly sent amongst every People a Messenger, (with the command): ‘Serve God, and eschew Evil;’ of the people were [as] some whom God guided, and some on whom Error became inevitably (established). So travel through the earth, and see what was the Ibid. p. 200, no. 4 end of those who denied (the Truth)” (Quran 16:36) This is because one of the principles by which God operates is that He will never take a people to task unless He has made clear to them what His expectations are. Article Source The Quran mentions the names of 25 prophets and indicates there were others. It says: “Of some messengers We have already told you the story; of others We have not; - and to Moses God spoke direct.” (Quran 4:164) We acknowledge that 'Our Messengers Way' by 'Harun Yahya' for providing the The Names of the 25 Prophets Mentioned are as follows: original file containing the 'Our Adam Messengers'.