Babur's Relations with the Ruling Elite and Tribes of the Punjab

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lodi Garden-A Historical Detour

Aditya Singh Rathod Subject: Soicial Science] [I.F. 5.761] Vol. 8, Issue: 6, June: 2020 International Journal of Research in Humanities & Soc. Sciences ISSN:(P) 2347-5404 ISSN:(O)2320 771X Lodi Garden-A Historical Detour ADITYA SINGH RATHOD Department of History University of Delhi, Delhi Lodi Garden, as a closed complex comprises of several architectural accomplishments such as tombs of Muhammad Shah and Sikandar Lodi, Bara Gumbad, Shish Gumbad (which is actually tomb of Bahlul Lodi), Athpula and many nameless mosque, however my field work primarily focuses upon the monuments constructed during the Lodi period. This term paper attempts to situate these monuments in the context of their socio-economic and political scenario through assistance of Waqiat-i-Mushtaqui and tries to traverse beyond the debate of sovereignty, which they have been confined within all these years. Village of Khairpur was the location of some of the tombs, mosques and other structures associated with the Lodi period, however in 1936; villagers were deported out of this space to lay the foundation of a closed campus named as Lady Willingdon Park, in the commemoration of erstwhile viceroy’s wife; later which was redesigned by eminent architect, J A Stein and was renamed as Lodi Garden in 1968. Its proximity to the Dargah of Shaykh Nizamuddin Auliya delineated Sufi jurisdiction over this space however, in due course of time it came under the Shia influence as Aliganj located nearby to it, houses monuments subscribing to this sect, such as Gateway of Old Karbala and Imambara; even the tomb of a powerful Shia Mughal governor i.e. -

Custodians of Culture and Biodiversity

Custodians of culture and biodiversity Indigenous peoples take charge of their challenges and opportunities Anita Kelles-Viitanen for IFAD Funded by the IFAD Innovation Mainstreaming Initiative and the Government of Finland The opinions expressed in this manual are those of the authors and do not nec - essarily represent those of IFAD. The designations employed and the presenta - tion of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IFAD concerning the legal status of any country, terri - tory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The designations “developed” and “developing” countries are in - tended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgement about the stage reached in the development process by a particular country or area. This manual contains draft material that has not been subject to formal re - view. It is circulated for review and to stimulate discussion and critical comment. The text has not been edited. On the cover, a detail from a Chinese painting from collections of Anita Kelles-Viitanen CUSTODIANS OF CULTURE AND BIODIVERSITY Indigenous peoples take charge of their challenges and opportunities Anita Kelles-Viitanen For IFAD Funded by the IFAD Innovation Mainstreaming Initiative and the Government of Finland Table of Contents Executive summary 1 I Objective of the study 2 II Results with recommendations 2 1. Introduction 2 2. Poverty 3 3. Livelihoods 3 4. Global warming 4 5. Land 5 6. Biodiversity and natural resource management 6 7. Indigenous Culture 7 8. Gender 8 9. -

Genetic Analysis of the Major Tribes of Buner and Swabi Areas Through Dental Morphology and Dna Analysis

GENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE MAJOR TRIBES OF BUNER AND SWABI AREAS THROUGH DENTAL MORPHOLOGY AND DNA ANALYSIS MUHAMMAD TARIQ DEPARTMENT OF GENETICS HAZARA UNIVERSITY MANSEHRA 2017 I HAZARA UNIVERSITY MANSEHRA Department of Genetics GENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE MAJOR TRIBES OF BUNER AND SWABI AREAS THROUGH DENTAL MORPHOLOGY AND DNA ANALYSIS By Muhammad Tariq This research study has been conducted and reported as partial fulfillment of the requirements of PhD degree in Genetics awarded by Hazara University Mansehra, Pakistan Mansehra The Friday 17, February 2017 I ABSTRACT This dissertation is part of the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan (HEC) funded project, “Enthnogenetic elaboration of KP through Dental Morphology and DNA analysis”. This study focused on five major ethnic groups (Gujars, Jadoons, Syeds, Tanolis, and Yousafzais) of Buner and Swabi Districts, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province, Pakistan, through investigations of variations in morphological traits of the permanent tooth crown, and by molecular anthropology based on mitochondrial and Y-chromosome DNA analyses. The frequencies of seven dental traits, of the Arizona State University Dental Anthropology System (ASUDAS) were scored as 17 tooth- trait combinations for each sample, encompassing a total sample size of 688 individuals. These data were compared to data collected in an identical fashion among samples of prehistoric inhabitants of the Indus Valley, southern Central Asia, and west-central peninsular India, as well as to samples of living members of ethnic groups from Abbottabad, Chitral, Haripur, and Mansehra Districts, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and to samples of living members of ethnic groups residing in Gilgit-Baltistan. Similarities in dental trait frequencies were assessed with C.A.B. -

Sayyid Dynasty

SAYYID DYNASTY The Sayyid dynasty was the fourth dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate, with four rulers ruling from 1414 to 1451. Founded by Khizr Khan, a former governor of Multan, they succeeded the Tughlaq dynasty and ruled the sultanate until they were displaced by the Lodi dynasty. Khizr Khan (1414- 1421 A.D.) He was the founder of Sayyid Dynasty He did not swear any royal title. He was the Governor of Multan. He took advantage of the disordered situation in India after Timur’s invasion. In 1414 A.D. he occupied the throne of Delhi. He brought parts of Surat, Dilapur, and Punjab under his control. But he lost Bengal, Deccan, Gujarat, Jaunpur, Khandesh and Malwa. In 1421 he died. Mubarak Shah, Khizr Khan’s son succeeded him. Mubarak Shah (1421-1434 A.D.) He was the son of Khizr Khan who got Khutba read on his name and issued his own coins. He did not accept the suzerainty of any foreign power. He was the ablest ruler of the dynasty. He subdued the rebellion at Bhatinda and Daob and the revolt by Khokhars Chief Jasrat. He patronised Vahiya Bin Ahmad Sarhind, author of Tarikh-i-Mubarak Shahi. Mubarak Shah was succeeded by two incompetent rulers, Muhammad Shah (AD 1434- 1445) and Alauddin Alam Shah (AD 1445-1450). Most of the provincial kingdoms declared their independence. Hence, Alam Shah surrendered the throne and retired in an inglorious manner to Baduan. Finally Bahlol Lodhi captured the throne of Delhi with the support of Wazir Khan. Muhammad Shah (1434-1445 A.D.) He defeated the ruler of Malwa with the help of Bahlul Lodi, the Governor of Lahore. -

Sayyid and Lodi Dynasty

Sayyid and Lodi Dynasty The Sayyid Dynasty (1414-1451 A.D.) सैय्यद वंश (1414-1451 A.D.) • Khizr Khan (1414- 1421 A.D.) • खिज्र िान (1414- 1421 ए.डी.) • He was the founder of Sayyid Dynasty • वह सैय्यद वंश के संथापक थे • He was the Governor of Multan. • वह मुल्तान के गवननर थे। • He took advantage of the disordered • उसने तैमूर के आक्रमण के बाद भारत मᴂ situation in India after Timur’s अव्यवखथत खथतत का लाभ उठाया। invasion. • 1414 ई मᴂ उसने तदल्ली के तसंहासन पर कब्जा • In 1414 A.D. he occupied the throne कर तलया। of Delhi. • उसने सूरत, तदलपुर और पंजाब के कुछ तहसं कस अपने तनयंत्रण मᴂ ले तलया। • He brought parts of Surat, Dilapur, • लेतकन उसने बंगाल, डेक्कन, गुजरात, जौनपुर, and Punjab under his control. िानदेश और मालवा कस िस तदया। • But he lost Bengal, Deccan, Gujarat, • 1421 मᴂ उसकी मृत्यु हस गई। Jaunpur, Khandesh and Malwa. • खिज्र िान के बाद उसका बेटा मुबारक शाह गद्दी • In 1421 he died. पर बैठा। • Mubarak Shah Khizr Khan’s son succeeded him. DLB 3 Mubarak Shah (1421-1434A.D.) मुबारक शाह (1421-1434A.D) • Mubarak Shah crushed the local • मुबारक शाह ने दसआब क्षेत्र के chiefs of the Doab region and थानीय प्रमुिसं और िसिरसं कस the Khokhars. कुचल तदया। • He is first Sultan ruler to • वह तदल्ली के दरबार मᴂ तहंदू रईससं कस तनयुक्त करने वाला पहला appoint Hindu nobles in the सुल्तान शासक था। court of Delhi. -

Walking with the Unicorn Social Organization and Material Culture in Ancient South Asia

Walking with the Unicorn Social Organization and Material Culture in Ancient South Asia Jonathan Mark KenoyerAccess Felicitation Volume Open Edited by Dennys Frenez, Gregg M. Jamison, Randall W. Law, Massimo Vidale and Richard H. Meadow Archaeopress Archaeopress Archaeology © Archaeopress and the authors, 2018. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978 1 78491 917 7 ISBN 978 1 78491 918 4 (e-Pdf) © ISMEO - Associazione Internazionale di Studi sul Mediterraneo e l'Oriente, Archaeopress and the authors 2018 Front cover: SEM microphotograph of Indus unicorn seal H95-2491 from Harappa (photograph by J. Mark Kenoyer © Harappa Archaeological Research Project). Access Back cover, background: Pot from the Cemetery H Culture levels of Harappa with a hoard of beads and decorative objects (photograph by Toshihiko Kakima © Prof. Hideo Kondo and NHK promotions). Back cover, box: Jonathan Mark Kenoyer excavating a unicorn seal found at Harappa (© Harappa Archaeological Research Project). Open ISMEO - Associazione Internazionale di Studi sul Mediterraneo e l'Oriente Corso Vittorio Emanuele II, 244 Palazzo Baleani Archaeopress Roma, RM 00186 www.ismeo.eu Serie Orientale Roma, 15 This volume was published with the financial assistance of a grant from the Progetto MIUR 'Studi e ricerche sulle culture dell’Asia e dell’Africa: tradizione e continuità, rivitalizzazione e divulgazione' All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by The Holywell Press, Oxford This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com © Archaeopress and the authors, 2018. -

An Overview of Medieval India

Dr. Rita Sharma Assistant Professor History An Overview of Medieval India Medieval period is an important period in the history of India because of the developments in the field of art and languages, culture and religion. Also the period has witnessed the impact of other religions on the Indian culture. Beginning of Medieval period is marked by the rise of the Rajput clan. This period is also referred to as Postclassical Era. Medieval period lasted from the 8th to the 18th century CE with early medieval period from the 8th to the 13th century and the late medieval period from the 13th to the 18th century. Early Medieval period witnessed wars among regional kingdoms from north and south India where as late medieval period saw the number of Muslim invasions by Mughals, Afghans and Turks. By the end of the fifteenth century European traders started doing trade and around mid- eighteenth century they became a political force in India marking the end of medieval period. But some scholars believe that start of Mughal Empire is the end of medieval period in India. Main Empires and Events in Medieval period Rajput Kingdoms – Rajput came for the first time in the 7th century AD. But historians gave different theories of their origin. After the mid-16th century, many Rajput rulers formed close relationships with the Mughal emperors and served them in different capacities. It was due to the support of the Rajputs that Akbar was able to lay the foundations of the Mughal Empire in India. Some Rajput nobles gave away their daughters in marriage to Mughal emperors and princes for political motives. -

Sl. No. Topic Page No. 1. Arab and Turk Invasions of India 1 2. Delhi Sultanate

VETRII IAS STUDY CIRCLE MEDIEVAL INDIA CONTENTS SL. PAGE TOPIC NO. NO. 1. ARAB AND TURK INVASIONS OF INDIA 1 2. DELHI SULTANATE 7 2.1 The Slave Dynasty (1206 - 1290 A.D.) 2.2 The Khalji Dynasty (1290 - 1320 A.D.) 2.3 Tughlak Dynasty (1320 - 1413 A.D.) 2.4 Sayyids Dynasty (1414 - 1451 A.D.) 2.5 Lodis Dynasty (1451 - 1526 A.D.) 3. VIJAYANAGARA EMPIRE 39 3.1 Sangama Dynasty 3.2 Saluva Dynasty 3.3 Tuluva Dynasty 3.4 Aravidu Dynasty 4. BAHMANI KINGDOM 50 4.1 Berar 4.2 Bidar 4.3 Ahmadnagar 4.4 Golconda 5. MUGHAL EMPIRE 59 www.vetriias.com VETRII IAS STUDY CIRCLE MEDIEVAL INDIA 5.1 Babur (1526 - 1530) 5.2 Humayun (1556 - 1605 AD) 5.3 Akbar (1556 - 1605 AD) 5.4 Jahangir (1605 - 1627 AD) 5.5 Shahjehan 1627 - 1658 AD) 5.6 Aurangazeb (1657 - 1707) 5.7 Mughal Administration 5.8 Art and Architecture of Mughals 6. THE MARATHA EMPIRE 101 6.1 Shivaji 6.2 Shivaji’s Administration www.vetriias.com VETRII IAS STUDY CIRCLE MEDIEVAL INDIA ❖ Firoz Tuglaq built cities like ❖ The sultan also opened a large Hissar, Firozabad, Fatehabad, number of free hospitals Dar-ul- Ferozpar and Janupur. shafa where medicines used to be distributed free to the people. ❖ Asokan stone pillars from Topara Experienced physicians, surgeons, and Merrut were brought to Delhi. eye specialists used to be appointed He also built a number of canals. who attended the patients with • Sirsa to Hansi great care. • Sutlej to Dipalpur ❖ Started practice of granting old-age • Yamuna to Sirmur pension. -

Audit Report on the Accounts of District Council and Municipal Committees Abbottabad Audit Year 2014-2015

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF DISTRICT COUNCIL AND MUNICIPAL COMMITTEES ABBOTTABAD AUDIT YEAR 2014-2015 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ......................................................................... i PREFACE ........................................................................................................................ ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................iii I: Audit work statistics ................................................................................................... vi II: Audit observation classified by catagories ................................................................ vi III: Outcome Statistics .................................................................................................... vii IV: Table of Irregularities pointed out .......................................................................... viii V: Cost-Benefit ………………………………………………………………………viii 1.1 District Council & Municipal Committees District Abbottabad……………1 1.1.1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Comments on Budget and Expenditure (variance analysis) ................................. 1 1.1.3 Comments on the status of compliance with ZAC/PAC Directives ................... 2 1.2 AUDIT PARAS DISTRICT COUNCIL ABBOTTABAD .............................. 3 1.2.1 Irregularity & Non-compliance ........................................................................... -

1 Component-I (A) – Personal Details

Component-I (A) – Personal details: 1 Component-I (B) – Description of module: Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Outlines of Indian History The Sayyid and Lodi Dynasties & Module Name/Title Salient features of the Delhi Sultanate Module Id I C / OIH / 23 Knowledge in Medieval history of India and the Pre-requisites rule of Delhi Sultanate To study the History of the Sayyid and Lodi Dynasties and Declining of the Delhi Sultanate. Objectives The contribution of Delhi Sultanates to Indian Culture Delhi Sultanate / Sayyid / Lodi / Indo-Persian Keywords Culture E-text (Quadrant-I) 1. The Sayyid dynasty (1414 - 1451) The Sayyid dynasty was the fourth dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate ruled from 1414 – 1451. This family claimed to be sayyids, or descendants of the Prophet Muhammad. The central authority of the Delhi sultanate had been fatally weakened by the invasion of the Turkish conqueror Timur and his capture of Delhi in 1398. Khizr Khan, who had been appointed Governor of Lahore, Multan and Dipalpur by Amir Timur, acquired control of Delhi after defeating its de facto ruler Daulat Khan. Taking advantage of the confusion that prevailed in India after the death of the last Tughlaq, Nasiruddin Mahmud Shah, Khizr Khan marched on Delhi, occupied the throne for himself on May 28, 1414 1. 1 Khizr Khan (1414-1421) Khizr Khan laid the foundation of a new dynasty of the Sayyids. He was a man of high moral character who combined in him the qualities of a saint, soldier and politician. Khizr Khan ruled Delhi independently for seven years. His kingdom comprising of Sindh, Punjab and some parts of the Doab. -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Ahmadi in Pakistan Ansari in Pakistan Population: 76,000 Population: 4,032,000 World Popl: 151,500 World Popl: 14,792,500 Total Countries: 3 Total Countries: 6 People Cluster: South Asia Muslim - other People Cluster: South Asia Muslim - Ansari Main Language: Punjabi, Western Main Language: Urdu Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.00% Evangelicals: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Scripture: New Testament Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Asma Mirza Source: Biswarup Ganguly "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Arain (Muslim traditions) in Pakistan Awan in Pakistan Population: 9,830,000 Population: 5,229,000 World Popl: 9,963,600 World Popl: 5,249,000 Total Countries: 3 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: South Asia Muslim - Arain People Cluster: South Asia Muslim - other Main Language: Punjabi, Western Main Language: Punjabi, Western Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.00% Evangelicals: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Scripture: New Testament Scripture: New Testament www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Imran Ali Arain Source: Galen Frysinger "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Badhai -

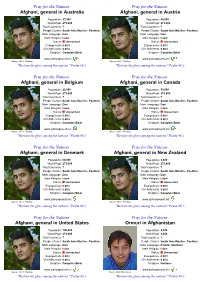

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Afghani, general in Australia Afghani, general in Austria Population: 27,000 Population: 44,000 World Popl: 279,600 World Popl: 279,600 Total Countries: 7 Total Countries: 7 People Cluster: South Asia Muslim - Pashtun People Cluster: South Asia Muslim - Pashtun Main Language: Dari Main Language: Dari Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.00% Evangelicals: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: fsHH - Pixabay Source: fsHH - Pixabay "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Afghani, general in Belgium Afghani, general in Canada Population: 26,000 Population: 59,000 World Popl: 279,600 World Popl: 279,600 Total Countries: 7 Total Countries: 7 People Cluster: South Asia Muslim - Pashtun People Cluster: South Asia Muslim - Pashtun Main Language: Dari Main Language: Dari Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.00% Evangelicals: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: fsHH - Pixabay Source: fsHH - Pixabay "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Afghani, general in Denmark Afghani,