The Clash and Fugazi: Punk Paths Toward Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson

The Interplay of Authority, Masculinity, and Signification in the “Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Holly Johnson ii Abstract This thesis will deconstruct the "grunge killed '80s metal” narrative, to reveal the idealization by certain critics and musicians of that which is deemed to be authentic, honest, and natural subculture. The central theme is an analysis of the conflicting masculinities of glam metal and grunge music, and how these gender roles are developed and reproduced. I will also demonstrate how, although the idealized authentic subculture is positioned in opposition to the mainstream, it does not in actuality exist outside of the system of commercialism. The problematic nature of this idealization will be examined with regard to the layers of complexity involved in popular rock music genre evolution, involving the inevitable progression from a subculture to the mainstream that occurred with both glam metal and grunge. I will illustrate the ways in which the process of signification functions within rock music to construct masculinities and within subcultures to negotiate authenticity. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my academic advisor Dr. William Echard for his continued patience with me during the thesis writing process and for his invaluable guidance. I also would like to send a big thank you to Dr. James Deaville, the head of Music and Culture program, who has given me much assistance along the way. -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Wickenden Wonderland, Dec 21, Rings in Holiday Spirit,H.R. From

Wickenden Wonderland, Dec 21, Rings In Holiday Spirit Caroling is part of the Christmas tradition. Ordinary folks gracing their neighborhood with their own style of holiday cheer is commonplace in many cities. Fox Point on the PVD East Side, one of the city’s neighborhoods with an artistic temperament, is putting their own spin on it. Wickenden Wonderland – Thursday, Dec 21, 6-8pm – is a celebration put together by the Fox Point Neighborhood Association, and it is for a great cause. Raising money for the homeless with Amos House, this wonderland provides a glimpse of beauty in the human spirit. It also looks like a damned good time. The start is the Point Tavern 6-7pm with drinks and plans for merrymaking. The kitchen will be occupied by Great Northern Barbeque, so it’s an opportunity to enjoy delicious food among friends. There will be drink specials at the Point, and their beverages are a great way to lubricate your singing voice – and no one should be caroling on an empty stomach. Revenue from food and drink sales will go toward Amos House. This all makes for a stellar reason to join in on the fun. At 7pm, the party moves to George M. Cohan Plaza (the intersection of Wickenden and Governor Streets) for what the event Facebook page describes as “great musical accompaniment of the Mighty Good Boys. There will be hot chocolate and cookies for everyone!” If you find yourself on PVD’s East Side or you’re in the city looking for something to do on a Thursday night, then celebrate the holiday season with a caroling crowd. -

THE WORLD PREMIERE CONCERT FILM of F*CK7THGRADE BEGINS STREAMING on JANUARY 25Th Singer/Songwriter Jill Sobule Shares Her Rock & Roll Life Story on Screen

CONTACT: Nikki Battestilli Marketing Director [email protected] CityTheatreCompany.org FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE WORLD PREMIERE CONCERT FILM OF F*CK7THGRADE BEGINS STREAMING ON JANUARY 25th Singer/Songwriter Jill Sobule Shares Her Rock & Roll Life Story On Screen Performers: Jill Sobule, Kristen Henderson, Sarah Siplak, and Julie Wolf Pittsburgh, PA (January 10, 2021): As the Covid-19 pandemic continues to prevent a safe return to indoor performances, City Theatre is excited to announce the world premiere concert film of F*ck7thGrade. F*ck7thGrade began its journey at City Theatre three years ago when Associate Artistic Director and dramaturg Clare Drobot met singer/songwriter Jill Sobule in New York. City Theatre paired Ms. Sobule with playwright Liza Birkenmeier, who wrote the book for the show, and workshopped and presented what would become F*ck7thGrade in the theater’s 2018 Momentum Festival of New Plays. After adding OBIE Award-winning director Lisa Peterson and music director Julie Wolf to the creative team, the show was further developed at the Colorado New Play Festival in Steamboat Springs and at Actor’s Express in Atlanta, supported by the National New Play Network. The world premiere production was slated as the final show of City Theatre’s 2019/20 season when the Covid-19 pandemic stopped live performances across the country. The team at City Theatre created an outdoor, drive-in venue at Hazelwood Green and staged the concert version of the show over three nights in front of an invited audience. Videographers Mickey and Molly Miller of Human Habits captured the show live and served as editors, working closely with the directors, sound engineer Brad Peterson, and City Theatre’s artistic staff to create this theatrical, multi-camera concert film. -

Rill^ 1980S DC

rill^ 1980S DC rii£!St MTEVOLUTIO N AND EVKllMSTINO KFFK Ai\ liXTEiniKM^ WITH GUY PICCIOTTO BY KATni: XESMITII, IiV¥y^l\^ IKWKK IXSTRUCTOU: MR. HiUfiHT FmAL DUE DATE: FEBRUilRY 10, SOOO BANNED IN DC PHOTOS m AHEcoorts FROM THE re POHK UMOEAG ROUND pg-ssi OH t^€^.S^ 2006 EPISCOPAL SCHOOL American Century Oral History Project Interviewee Release Form I, ^-/ i^ji^ I O'nc , hereby give and grant to St. Andrew's (interviewee) Episcopal School llie absolute and unqualified right to the use ofmy oral history memoir conducted by KAi'lL I'i- M\-'I I on / // / 'Y- .1 understand that (student interviewer) (date) the purpose of (his project is to collect audio- and video-taped oral histories of first-hand memories ofa particular period or event in history as part of a classroom project (The American Century Project). 1 understand that these interviews (tapes and transcripts) will be deposited in the Saint Andrew's Episcopal School library and archives for the use by ftiture students, educators and researchers. Responsibility for the creation of derivative works will be at the discretion of the librarian, archivist and/or project coordinator. I also understand that the tapes and transcripts may be used in public presentations including, but not limited to, books, audio or video doe\imcntaries, slide-tape presentations, exhibits, articles, public performance, or presentation on the World Wide Web at t!ic project's web site www.americaiicenturyproject.org or successor technologies. In making this contract I understand that I am sharing with St. Andrew's Episcopal School librai-y and archives all legal title and literary property rights which i have or may be deemed to have in my inten'iew as well as my right, title and interest in any copyright related to this oral history interview which may be secured under the laws now or later in force and effect in the United States of America. -

Lesbian and Gay Music

Revista Eletrônica de Musicologia Volume VII – Dezembro de 2002 Lesbian and Gay Music by Philip Brett and Elizabeth Wood the unexpurgated full-length original of the New Grove II article, edited by Carlos Palombini A record, in both historical documentation and biographical reclamation, of the struggles and sensi- bilities of homosexual people of the West that came out in their music, and of the [undoubted but unacknowledged] contribution of homosexual men and women to the music profession. In broader terms, a special perspective from which Western music of all kinds can be heard and critiqued. I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 II. (HOMO)SEXUALIT Y AND MUSICALIT Y 2 III. MUSIC AND THE LESBIAN AND GAY MOVEMENT 7 IV. MUSICAL THEATRE, JAZZ AND POPULAR MUSIC 10 V. MUSIC AND THE AIDS/HIV CRISIS 13 VI. DEVELOPMENTS IN THE 1990S 14 VII. DIVAS AND DISCOS 16 VIII. ANTHROPOLOGY AND HISTORY 19 IX. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 24 X. EDITOR’S NOTES 24 XI. DISCOGRAPHY 25 XII. BIBLIOGRAPHY 25 I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 What Grove printed under ‘Gay and Lesbian Music’ was not entirely what we intended, from the title on. Since we were allotted only two 2500 words and wrote almost five times as much, we inevitably expected cuts. These came not as we feared in the more theoretical sections, but in certain other tar- geted areas: names, popular music, and the role of women. Though some living musicians were allowed in, all those thought to be uncomfortable about their sexual orientation’s being known were excised, beginning with Boulez. -

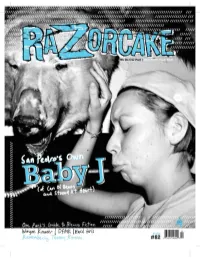

Razorcake Issue #82 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California not-for-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #Bamnextwave

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #BAMNextWave Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Katy Clark, Chairman of the Board President William I. Campbell, Joseph V. Melillo, Vice Chairman of the Board Executive Producer Place BAM Harvey Theater Oct 11—13 at 7:30pm; Oct 13 at 2pm Running time: approx. one hour 15 minutes, no intermission Created by Ted Hearne, Patricia McGregor, and Saul Williams Music by Ted Hearne Libretto by Saul Williams and Ted Hearne Directed by Patricia McGregor Conducted by Ted Hearne Scenic design by Tim Brown and Sanford Biggers Video design by Tim Brown Lighting design by Pablo Santiago Costume design by Rachel Myers and E.B. Brooks Sound design by Jody Elff Assistant director Jennifer Newman Co-produced by Beth Morrison Projects and LA Phil Season Sponsor: Leadership support for music programs at BAM provided by the Baisley Powell Elebash Fund Major support for Place provided by Agnes Gund Place FEATURING Steven Bradshaw Sophia Byrd Josephine Lee Isaiah Robinson Sol Ruiz Ayanna Woods INSTRUMENTAL ENSEMBLE Rachel Drehmann French Horn Diana Wade Viola Jacob Garchik Trombone Nathan Schram Viola Matt Wright Trombone Erin Wight Viola Clara Warnaar Percussion Ashley Bathgate Cello Ron Wiltrout Drum Set Melody Giron Cello Taylor Levine Electric Guitar John Popham Cello Braylon Lacy Electric Bass Eileen Mack Bass Clarinet/Clarinet RC Williams Keyboard Christa Van Alstine Bass Clarinet/Contrabass Philip White Electronics Clarinet James Johnston Rehearsal pianist Gareth Flowers Trumpet ADDITIONAL PRODUCTION CREDITS Carolina Ortiz Herrera Lighting Associate Lindsey Turteltaub Stage Manager Shayna Penn Assistant Stage Manager Co-commissioned by the Los Angeles Phil, Beth Morrison Projects, Barbican Centre, Lynn Loacker and Elizabeth & Justus Schlichting with additional commissioning support from Sue Bienkowski, Nancy & Barry Sanders, and the Francis Goelet Charitable Lead Trusts. -

La Fugazi Live Series Sylvain David

Document generated on 10/01/2021 9:37 p.m. Sens public « Archive-it-yourself » La Fugazi Live Series Sylvain David (Re)constituer l’archive Article abstract 2016 Fugazi, one of the most respected bands of the American independent music scene, recently posted almost all of its live performances online, releasing over URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1044387ar 800 recordings made between 1987 and 2003. Such a project is atypical both by DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1044387ar its size, rock groups being usually content to produce one or two live albums during the scope of their career, and by its perspective, Dischord Records, an See table of contents independent label, thus undertaking curatorial activities usually supported by official cultural institutions such as museums, libraries and universities. This approach will be considered here both in terms of documentation, the infinite variations of the concerts contrasting with the arrested versions of the studio Publisher(s) albums, and of the musical canon, Fugazi obviously wishing, by the Département des littératures de langue française constitution of this digital archive, to contribute to a parallel rock history. ISSN 2104-3272 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article David, S. (2016). « Archive-it-yourself » : la Fugazi Live Series. Sens public. https://doi.org/10.7202/1044387ar Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) Sens-Public, 2016 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. -

Bad Rhetoric: Towards a Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2012 Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Utley, Michael, "Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy" (2012). All Theses. 1465. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1465 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BAD RHETORIC: TOWARDS A PUNK ROCK PEDAGOGY A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Professional Communication by Michael M. Utley August 2012 Accepted by: Dr. Jan Rune Holmevik, Committee Chair Dr. Cynthia Haynes Dr. Scot Barnett TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ..........................................................................................................................4 Theory ................................................................................................................................32 The Bad Brains: Rhetoric, Rage & Rastafarianism in Early 1980s Hardcore Punk ..........67 Rise Above: Black Flag and the Foundation of Punk Rock’s DIY Ethos .........................93 Conclusion .......................................................................................................................109 -

Download PDF > Riot Grrrl \\ 3Y8OTSVISUJF

LWSRQOQGSW3L / Book ~ Riot grrrl Riot grrrl Filesize: 8.18 MB Reviews Unquestionably, this is actually the very best work by any article writer. It usually does not price a lot of. Once you begin to read the book, it is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding. (Augustine Pfannerstill) DISCLAIMER | DMCA GOKP10TMWQNH / Kindle ~ Riot grrrl RIOT GRRRL To download Riot grrrl PDF, make sure you refer to the button under and download the document or gain access to other information which might be related to RIOT GRRRL book. Reference Series Books LLC Jan 2012, 2012. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 249x189x10 mm. Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 54. Chapters: Kill Rock Stars, Sleater-Kinney, Tobi Vail, Kathleen Hanna, Lucid Nation, Jessicka, Carrie Brownstein, Kids Love Lies, G. B. Jones, Sharon Cheslow, The Shondes, Jack O Jill, Not Bad for a Girl, Phranc, Bratmobile, Fih Column, Caroline Azar, Bikini Kill, Times Square, Jen Smith, Nomy Lamm, Huggy Bear, Karen Finley, Bidisha, Kaia Wilson, Emily's Sassy Lime, Mambo Taxi, The Yo-Yo Gang, Ladyfest, Bangs, Shopliing, Mecca Normal, Voodoo Queens, Sister George, Heavens to Betsy, Donna Dresch, Allison Wolfe, Billy Karren, Kathi Wilcox, Tattle Tale, Sta-Prest, All Women Are Bitches, Excuse 17, Pink Champagne, Rise Above: The Tribe 8 Documentary, Juliana Luecking, Lungleg, Rizzo, Tammy Rae Carland, The Frumpies, Lisa Rose Apramian, List of Riot Grrl bands, 36-C, Girl Germs, Cold Cold Hearts, Frightwig, Yer So Sweet, Direction, Viva Knievel. Excerpt: Riot grrrl was an underground feminist punk movement based in Washington, DC, Olympia, Washington, Portland, Oregon, and the greater Pacific Northwest which existed in the early to mid-1990s, and it is oen associated with third-wave feminism (it is sometimes seen as its starting point). -

Ahead of Their Time

NUMBER 2 2013 Ahead of Their Time About this Issue In the modern era, it seems preposterous that jazz music was once National Council on the Arts Joan Shigekawa, Acting Chair considered controversial, that stream-of-consciousness was a questionable Miguel Campaneria literary technique, or that photography was initially dismissed as an art Bruce Carter Aaron Dworkin form. As tastes have evolved and cultural norms have broadened, surely JoAnn Falletta Lee Greenwood we’ve learned to recognize art—no matter how novel—when we see it. Deepa Gupta Paul W. Hodes Or have we? When the NEA first awarded grants for the creation of video Joan Israelite Maria Rosario Jackson games about art or as works of art, critical reaction was strong—why was Emil Kang the NEA supporting something that was entertainment, not art? Yet in the Charlotte Kessler María López De León past 50 years, the public has debated the legitimacy of street art, graphic David “Mas” Masumoto Irvin Mayfield, Jr. novels, hip-hop, and punk rock, all of which are now firmly established in Barbara Ernst Prey the cultural canon. For other, older mediums, such as television, it has Frank Price taken us years to recognize their true artistic potential. Ex-officio Sen. Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) In this issue of NEA Arts, we’ll talk to some of the pioneers of art Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) Rep. Betty McCollum (D-MN) forms that have struggled to find acceptance by the mainstream. We’ll Rep. Patrick J. Tiberi (R-OH) hear from Ian MacKaye, the father of Washington, DC’s early punk scene; Appointment by Congressional leadership of the remaining ex-officio Lady Pink, one of the first female graffiti artists to rise to prominence in members to the council is pending.