Modulation of Gene Expression in Heart and Liver of Hibernating Black Bears (Ursus Americanus)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reprogramming of Trna Modifications Controls the Oxidative Stress Response by Codon-Biased Translation of Proteins

Reprogramming of tRNA modifications controls the oxidative stress response by codon-biased translation of proteins The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Chan, Clement T.Y. et al. “Reprogramming of tRNA Modifications Controls the Oxidative Stress Response by Codon-biased Translation of Proteins.” Nature Communications 3 (2012): 937. As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1938 Publisher Nature Publishing Group Version Author's final manuscript Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/76775 Terms of Use Article is made available in accordance with the publisher's policy and may be subject to US copyright law. Please refer to the publisher's site for terms of use. Reprogramming of tRNA modifications controls the oxidative stress response by codon-biased translation of proteins Clement T.Y. Chan,1,2 Yan Ling Joy Pang,1 Wenjun Deng,1 I. Ramesh Babu,1 Madhu Dyavaiah,3 Thomas J. Begley3 and Peter C. Dedon1,4* 1Department of Biological Engineering, 2Department of Chemistry and 4Center for Environmental Health Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139; 3College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering, University at Albany, SUNY, Albany, NY 12203 * Corresponding author: PCD, Department of Biological Engineering, NE47-277, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139; tel 617-253-8017; fax 617-324-7554; email [email protected] 2 ABSTRACT Selective translation of survival proteins is an important facet of cellular stress response. We recently demonstrated that this translational control involves a stress-specific reprogramming of modified ribonucleosides in tRNA. -

Allele-Specific Expression of Ribosomal Protein Genes in Interspecific Hybrid Catfish

Allele-specific Expression of Ribosomal Protein Genes in Interspecific Hybrid Catfish by Ailu Chen A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama August 1, 2015 Keywords: catfish, interspecific hybrids, allele-specific expression, ribosomal protein Copyright 2015 by Ailu Chen Approved by Zhanjiang Liu, Chair, Professor, School of Fisheries, Aquaculture and Aquatic Sciences Nannan Liu, Professor, Entomology and Plant Pathology Eric Peatman, Associate Professor, School of Fisheries, Aquaculture and Aquatic Sciences Aaron M. Rashotte, Associate Professor, Biological Sciences Abstract Interspecific hybridization results in a vast reservoir of allelic variations, which may potentially contribute to phenotypical enhancement in the hybrids. Whether the allelic variations are related to the downstream phenotypic differences of interspecific hybrid is still an open question. The recently developed genome-wide allele-specific approaches that harness high- throughput sequencing technology allow direct quantification of allelic variations and gene expression patterns. In this work, I investigated allele-specific expression (ASE) pattern using RNA-Seq datasets generated from interspecific catfish hybrids. The objective of the study is to determine the ASE genes and pathways in which they are involved. Specifically, my study investigated ASE-SNPs, ASE-genes, parent-of-origins of ASE allele and how ASE would possibly contribute to heterosis. My data showed that ASE was operating in the interspecific catfish system. Of the 66,251 and 177,841 SNPs identified from the datasets of the liver and gill, 5,420 (8.2%) and 13,390 (7.5%) SNPs were identified as significant ASE-SNPs, respectively. -

Elabscience.Com ® E-Mail:[email protected] Elabscience Elabscience Biotechnology Inc

Tel:240-252-7368(USA) Fax:240-252-7376(USA) www.elabscience.com ® E-mail:[email protected] Elabscience Elabscience Biotechnology Inc. RPL7 Polyclonal Antibody Catalog No. E-AB-32805 Reactivity H,M,R Storage Store at -20℃. Avoid freeze / thaw cycles. Host Rabbit Applications WB,IHC-p,ELISA Isotype IgG Note: Centrifuge before opening to ensure complete recovery of vial contents. Images Immunogen Information Immunogen Synthesized peptide derived from the C-terminal region of human Ribosomal Protein L7 Swissprot P18124 Synonyms RPL7,60S ribosomal protein L7 Western Blot analysis of 293 cells Product Information using RPL7 Polyclonal Antibody at Calculated MW 29kDa dilution of 1:2000. Observed MW 32kDa Buffer PBS with 0.02% sodium azide, 0.5% BSA and 50% glycerol, pH7.4 Purify Affinity purification Dilution WB 1:500-1:2000, IHC 1:100-1:300, ELISA 1:10000 Background Ribosomes, the organelles that catalyze protein synthesis, consist of a small 40S subunit and a large 60S subunit. Together these subunits are composed of 4 RNA species and approximately 80 structurally distinct proteins. This gene encodes a ribosomal protein that is a component of the 60S subunit. The protein belongs to the L30P family of ribosomal proteins. It contains an N-terminal basic region-leucine zipper (BZIP)-like domain and the RNP consensus submotif RNP2. In vitro the BZIP-like domain mediates homodimerization and stable binding to DNA and RNA, with a preference for 28S rRNA and mRNA. The protein can inhibit cell- free translation of mRNAs, suggesting that it plays a regulatory role in the translation apparatus. -

Attachment PDF Icon

Spectrum Name of Protein Count of Peptides Ratio (POL2RA/IgG control) POLR2A_228kdBand POLR2A DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit RPB1 197 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand POLR2B DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit RPB2 146 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand RPAP2 Isoform 1 of RNA polymerase II-associated protein 2 24 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand POLR2G DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit RPB7 23 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand POLR2H DNA-directed RNA polymerases I, II, and III subunit RPABC3 19 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand POLR2C DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit RPB3 17 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand POLR2J RPB11a protein 7 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand POLR2E DNA-directed RNA polymerases I, II, and III subunit RPABC1 8 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand POLR2I DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit RPB9 9 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand ALMS1 ALMS1 3 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand POLR2D DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit RPB4 6 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand GRINL1A;Gcom1 Isoform 12 of Protein GRINL1A 6 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand RECQL5 Isoform Beta of ATP-dependent DNA helicase Q5 3 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand POLR2L DNA-directed RNA polymerases I, II, and III subunit RPABC5 5 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand KRT6A Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 6A 3 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand POLR2K DNA-directed RNA polymerases I, II, and III subunit RPABC4 2 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand RFC4 Replication factor C subunit 4 1 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand RFC2 -

Inflammation Leads to Distinct Populations of Extracellular Vesicles from Microglia Yiyi Yang1* , Antonio Boza-Serrano1, Christopher J

Yang et al. Journal of Neuroinflammation (2018) 15:168 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-018-1204-7 RESEARCH Open Access Inflammation leads to distinct populations of extracellular vesicles from microglia Yiyi Yang1* , Antonio Boza-Serrano1, Christopher J. R. Dunning2, Bettina Hjelm Clausen3,4, Kate Lykke Lambertsen3,4,5 and Tomas Deierborg1* Abstract Background: Activated microglia play an essential role in inflammatory responses elicited in the central nervous system (CNS). Microglia-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) are suggested to be involved in propagation of inflammatory signals and in the modulation of cell-to-cell communication. However, there is a lack of knowledge on the regulation of EVs and how this in turn facilitates the communication between cells in the brain. Here, we characterized microglial EVs under inflammatory conditions and investigated the effects of inflammation on the EV size, quantity, and protein content. Methods: We have utilized western blot, nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA), and mass spectrometry to characterize EVs and examine the alterations of secreted EVs from a microglial cell line (BV2) following lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor (etanercept) treatments, or either alone. The inflammatory responses were measured with multiplex cytokine ELISA and western blot. We also subjected TNF knockout mice to experimental stroke (permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion) and validated the effect of TNF inhibition on EV release. Results: Our analysis of EVs originating from activated BV2 microglia revealed a significant increase in the intravesicular levels of TNF and interleukin (IL)-6. We also observed that the number of EVs released was reduced both in vitro and in vivo when inflammation was inhibited via the TNF pathway. -

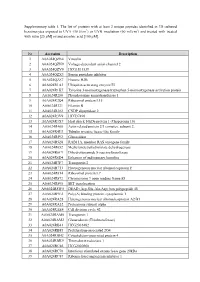

Supplementary Table 1. the List of Proteins with at Least 2 Unique

Supplementary table 1. The list of proteins with at least 2 unique peptides identified in 3D cultured keratinocytes exposed to UVA (30 J/cm2) or UVB irradiation (60 mJ/cm2) and treated with treated with rutin [25 µM] or/and ascorbic acid [100 µM]. Nr Accession Description 1 A0A024QZN4 Vinculin 2 A0A024QZN9 Voltage-dependent anion channel 2 3 A0A024QZV0 HCG1811539 4 A0A024QZX3 Serpin peptidase inhibitor 5 A0A024QZZ7 Histone H2B 6 A0A024R1A3 Ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 7 A0A024R1K7 Tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein 8 A0A024R280 Phosphoserine aminotransferase 1 9 A0A024R2Q4 Ribosomal protein L15 10 A0A024R321 Filamin B 11 A0A024R382 CNDP dipeptidase 2 12 A0A024R3V9 HCG37498 13 A0A024R3X7 Heat shock 10kDa protein 1 (Chaperonin 10) 14 A0A024R408 Actin related protein 2/3 complex, subunit 2, 15 A0A024R4U3 Tubulin tyrosine ligase-like family 16 A0A024R592 Glucosidase 17 A0A024R5Z8 RAB11A, member RAS oncogene family 18 A0A024R652 Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 19 A0A024R6C9 Dihydrolipoamide S-succinyltransferase 20 A0A024R6D4 Enhancer of rudimentary homolog 21 A0A024R7F7 Transportin 2 22 A0A024R7T3 Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein F 23 A0A024R814 Ribosomal protein L7 24 A0A024R872 Chromosome 9 open reading frame 88 25 A0A024R895 SET translocation 26 A0A024R8W0 DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 48 27 A0A024R9E2 Poly(A) binding protein, cytoplasmic 1 28 A0A024RA28 Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1 29 A0A024RA52 Proteasome subunit alpha 30 A0A024RAE4 Cell division cycle 42 31 -

Inhibition of the MID1 Protein Complex

Matthes et al. Cell Death Discovery (2018) 4:4 DOI 10.1038/s41420-017-0003-8 Cell Death Discovery ARTICLE Open Access Inhibition of the MID1 protein complex: a novel approach targeting APP protein synthesis Frank Matthes1,MoritzM.Hettich1, Judith Schilling1, Diana Flores-Dominguez1, Nelli Blank1, Thomas Wiglenda2, Alexander Buntru2,HannaWolf1, Stephanie Weber1,InaVorberg 1, Alina Dagane2, Gunnar Dittmar2,3,ErichWanker2, Dan Ehninger1 and Sybille Krauss1 Abstract Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by two neuropathological hallmarks: senile plaques, which are composed of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides, and neurofibrillary tangles, which are composed of hyperphosphorylated tau protein. Aβ peptides are derived from sequential proteolytic cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein (APP). In this study, we identified a so far unknown mode of regulation of APP protein synthesis involving the MID1 protein complex: MID1 binds to and regulates the translation of APP mRNA. The underlying mode of action of MID1 involves the mTOR pathway. Thus, inhibition of the MID1 complex reduces the APP protein level in cultures of primary neurons. Based on this, we used one compound that we discovered previously to interfere with the MID1 complex, metformin, for in vivo experiments. Indeed, long-term treatment with metformin decreased APP protein expression levels and consequently Aβ in an AD mouse model. Importantly, we have initiated the metformin treatment late in life, at a time-point where mice were in an already progressed state of the disease, and could observe an improved behavioral phenotype. These 1234567890 1234567890 findings together with our previous observation, showing that inhibition of the MID1 complex by metformin also decreases tau phosphorylation, make the MID1 complex a particularly interesting drug target for treating AD. -

Supplementary Table S1. Protein Expression Changes in the Functionally Annotated Categories Within Cluster from Figure 8A

Supplementary Table S1. Protein expression changes in the functionally annotated categories within cluster from Figure 8A. Acute phase response signaling Human equivalent Zq (log2 FC) FDR Accession No. Ac. No. No. Protein 120 1 4 7 120 1 4 7 peptides Q13233 F1SLK9 PIG Uncharacterized protein MAP3K1 0.09 0.00 0.00 0.55 1 - I3LQR9 PIG Fibrinogen alpha chain 0.89 0.23 0.03 0.11 11 - F1RX36 PIG Fibrinogen alpha chain 0.97 0.09 0.00 0.09 4 P02675 I3L651 PIG Uncharacterized protein 0.91 0.24 0.05 0.23 27 - Q8SPS7 PIG Haptoglobin 0.11 0.02 0.00 0.36 14 P45985 F1SS51 PIG Uncharacterized protein (Fragment) MAP2K4 0.26 0.06 0.09 0.33 1 - P00747 HUMAN Plasminogen 0.93 0.00 0.02 0.67 1 - P18648 PIG Apolipoprotein A-I 0.36 0.19 0.64 0.86 34 P02679 F1RX35 PIG Uncharacterized protein LOC100627396 0.99 0.40 0.02 0.11 23 P04196 F1SFI5 PIG Uncharacterized protein HRG 0.44 0.04 0.55 0.82 12 - P27485 PIG Retinol-binding protein 4 0.34 0.30 0.55 0.81 2 - F1S0J2 PIG Uncharacterized protein C4BPA 0.58 0.17 0.15 0.65 4 - P08835 PIG Serum albumin 0.04 0.09 0.39 0.75 27 - P06867 PIG Plasminogen 0.94 0.17 0.08 0.82 13 - O19063 PIG Serum amyloid P-component 0.93 0.16 0.09 0.85 6 - O19062 PIG C-reactive protein 0.93 0.01 0.00 0.78 7 - P00450 HUMAN Ceruloplasmin 0.32 0.61 0.36 0.41 1 - F1SB81 PIG Plasminogen 0.99 0.17 0.14 0.52 2 - Q19AZ8 PIG Prothrombin 0.36 0.08 0.54 0.90 6 - I3L818 PIG Uncharacterized protein (Fragment) SERPINF2 0.91 0.59 0.12 0.65 4 P05546 F1RKY2 PIG Uncharacterized protein SERPIND1 0.38 0.44 0.72 0.86 9 P02749 I3LGN5 PIG Uncharacterized protein -

Ribosomal Protein Mutants and Their Effects on Plant Growth and Development

RIBOSOMAL PROTEIN MUTANTS AND THEIR EFFECTS ON PLANT GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Department of Biology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Chad Dale Stewart © Copyright Chad Stewart, November, 2012. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Biology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5E2 i ABSTRACT Ribosomes, large enzymatic complexes containing an RNA catalytic core, drive protein synthesis in all living organisms. -

Gene Symbol Gene Name Start Stop Non-Synonymous Polymorphism

Non-Synonymous Gene Symbol Gene Name Start Stop Polymorphism Sdcbp2 Syndecan binding protein (syntenin) 2 141,891,232 141,919,905 I82V Snph Syntaphilin 141,921,547 141,961,697 A411T, 415_420* Rad21l1 RAD21-like 1 (S. pombe) 141,984,729 142,009,665 LOC100363280 mCG140681-like 142,022,959 142,030,458 RGD1564048 Similar to Protein C20orf46 142,043961 142,047,717 Similar to Proteasome inhibitor PI31 LOC689852 142,058,695 142,083,908 subunit LOC100363380 Hypothetical LOC100363380 142,139,020 142,143,826 Rspo4 R-spondin family, member 4 142,185,028 142,216,015 Angpt4 Angiopoietin 4 142,249,115 142,282,307 Family with sequence similarity 110, Fam110a 142,326,013 142,328,572 member A LOC689884 Hypothetical protein LOC689884 142,335,923 142,336,396 LOC100363434 Ribosomal protein S29-like 142,339,596 142,341,169 RGD1304644 Similar to RIKEN cDNA 2310046K01 142,360,661 142,365,285 Scratch homolog 2, zinc finger protein Scrt2 142,434,272 142,445,984 (Drosophila) Srxn1 Sulfiredoxin 1 homolog (S. cerevisiae) 142,457,352 142,462,725 Tcf15 Transcription factor 15 142,491,664 142,497,446 Csnk2a1 Casein kinase 2, alpha 1 polypeptide 142,564,754 142,609,311 Tbc1d20 TBC1 domain family, member 20 142,623,713 142,640,197 RanBP-type and C3HC4-type zinc finger Rbck1 142,644,156 142,660,799 containing 1 Trib3 Tribbles homolog 3 (Drosophila) 142,664,641 142,670,135 Nrsn2 Neurensin 2 142,692,988 142,702,131 Sox12 SRY (sex determining region Y)-box 12 142,714,836 142,715,855 Zcchc3 Zinc finger, CCHC domain containing 3 142,727,648 142,730,465 LOC502684 Hypothetical -

Enhanced Autophagic-Lysosomal Activity and Increased BAG3- Mediated Selective Macroautophagy As Adaptive Response of Neuronal Ce

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/580977; this version posted March 18, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Enhanced autophagic-lysosomal activity and increased BAG3- mediated selective macroautophagy as adaptive response of neuronal cells to chronic oxidative stress Debapriya Chakraborty1, Vanessa Felzen1, Christof Hiebel1, Elisabeth Stürner1, Natarajan Perumal2, Caroline Manicam2, Elisabeth Sehn3, Franz Grus2, Uwe Wolfrum3, Christian Behl1* 1Institute of Pathobiochemistry, University Medical Center Mainz of the Johannes Gutenberg University, 55099 Mainz, Germany 2Experimental and Translational Ophthalmology, University Medical Center Mainz, 55131 Mainz, Germany 3 Institute for Molecular Physiology, Johannes Gutenberg University, 55128 Mainz, Germany E-mail addresses of authors: D. Chakraborty: [email protected]; V. Felzen: [email protected]; C. Hiebel: [email protected]; E. Stürner: [email protected]; N. Perumal: nperumal@eye- research.org; C. Manicam: [email protected]; E. Sehn: sehn@uni- mainz.de; F. Grus: [email protected]; U. Wolfrum: [email protected]; *Correspondence to Christian Behl, PhD Institute of Pathobiochemistry University Medical Center of the Johannes Gutenberg University Duesbergweg 6, D-55099 Mainz [email protected] Tel.: +49-6131-39-25890; Fax: +49-6131-39-25792 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/580977; this version posted March 18, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract Oxidative stress and a disturbed cellular protein homeostasis (proteostasis) belong to the most important hallmarks of aging and of neurodegenerative disorders. -

ACTG BOVIN Actin, Cytoplasmic 2 OS=Bos Taurus OX=9913 GN=ACTG1 PE=1 SV=1 TBB4B MOUSE Tubulin Beta-4B Chain OS=Mus Musculus OX=10

Supplementary Data 2. Proteomics results, neurons Actin, cytoplasmic 2 OS=Bos taurus OX=9913 ACTG_BOVIN GN=ACTG1 PE=1 SV=1 Tubulin beta-4B chain OS=Mus musculus TBB4B_MOUSE OX=10090 GN=Tubb4b PE=1 SV=1 Spectrin alpha chain, non-erythrocytic 1 OS=Mus SPTN1_MOUSE musculus OX=10090 GN=Sptan1 PE=1 SV=4 Sodium/potassium-transporting ATPase subunit AT1A3_MOUSE alpha-3 OS=Mus musculus OX=10090 GN=Atp1a3 PE=1 SV=1 Spectrin beta chain, non-erythrocytic 1 OS=Mus SPTB2_MOUSE musculus OX=10090 GN=Sptbn1 PE=1 SV=2 Heat shock protein HSP 90-beta OS=Mus HS90B_MOUSE musculus OX=10090 GN=Hsp90ab1 PE=1 SV=3 Myosin-10 OS=Mus musculus OX=10090 MYH10_MOUSE GN=Myh10 PE=1 SV=2 ATP synthase subunit beta, mitochondrial ATPB_MOUSE OS=Mus musculus OX=10090 GN=Atp5f1b PE=1 SV=2 Heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein OS=Mus HSP7C_MOUSE musculus OX=10090 GN=Hspa8 PE=1 SV=1 Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase G3P_MOUSE OS=Mus musculus OX=10090 GN=Gapdh PE=1 SV=2 Elongation factor 1-alpha 1 OS=Mus musculus EF1A1_MOUSE OX=10090 GN=Eef1a1 PE=1 SV=3 Ubiquitin-like modifier-activating enzyme 1 UBA1_MOUSE OS=Mus musculus OX=10090 GN=Uba1 PE=1 SV=1 Microtubule-associated protein 1B OS=Mus MAP1B_MOUSE musculus OX=10090 GN=Map1b PE=1 SV=2 Transitional endoplasmic reticulum ATPase TERA_HUMAN OS=Homo sapiens OX=9606 GN=VCP PE=1 SV=4 Elongation factor 2 OS=Mus musculus EF2_MOUSE OX=10090 GN=Eef2 PE=1 SV=2 ATP synthase subunit alpha, mitochondrial ATPA_MOUSE OS=Mus musculus OX=10090 GN=Atp5f1a PE=1 SV=1 Fatty acid synthase OS=Mus musculus OX=10090 FAS_MOUSE GN=Fasn PE=1 SV=2 60