Don't You Avant Me, Baby?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

David S. Ware in Profile

Steve Coleman: The Most Influential Figure Since Coltrane? AMERICA’s JAZZ MAGAZINE Win a Trip for Two on The Jazz Cruise! TBetweenia Fuller Bop&Beyoncé David S. Ware Fred Ho in Profile His Harrowing BY DAVID R. ADLER Fight Against Cancer Before & After Lee Konitz Nate Chinen on Kirk Whalum John Ellis A $250,000 Turntable? Audiophile Gear to Die For Stan Getz & Kenny Barron Reviewed 40 JAZZTIMES >> JUNE 2010 A f te r the here were torrential rains, and gusts up to 60 miles per hour, on the night in mid- March when saxophone icon David S. Ware played solo before an intimate crowd in Brooklyn. Seated in the cozy home office of host Garrett Shelton, a music industry con- sultant, Ware began with an assertive, envel- Still coping with the oping improvisation on sopranino—a new Thorn in his arsenal—and followed it with an S toaftermath of a rkidney m extended tenor display, rigorously developed, with mounting sonic power. transplant, David S. Ware After he finished, Ware played up the salon-like atmosphere by inviting questions forges ahead with solo from listeners. Multi-instrumentalist Cooper- Moore, Ware’s good friend and one-time saxophone, a new trio roommate, who (like me) nearly missed the show on account of a subway power outage, and a return to the Vision was among the first to speak. He noted that the weather was also perfectly miserable on Festival this summer Oct. 15, 2009, the night of Ware’s previous solo concert. So one had to wonder, “What’s goin’ on with you, man?” Laughing, Ware By David R. -

Shipp / Lehn / Butcher

SHIPP / LEHN / BUTCHER John Butcher [UK] • soprano- & tenor saxophone, feedback Thomas Lehn [AT/DE] • analogue synthesizer Matthew Shipp [USA] • piano © painting by Gina Southgate @ Konfrontationen 2016 The combination of personalities is winningly combustible. The rhythmic push and pull between Butcher, Shipp and Lehn is a delight, with all three conjuring up graciously dissonant figures whose frequent crisscrossing gives the music a kaleidoscopic character. All of the players are drumming with razor sharp focus, but they also have more serene impulses and create glistening soundscapes in which the analogue keyboard is well complemented by the two acoustic instruments that are inspired to match the strange and beautiful noise that fills the air. Music with an on-the-edge intensity that is nonetheless handled with considerable rigour and attention to detail. - Kevin Le Gendre | Jazzwise Magazine | Feb 2017 CD release Tangle label: Fataka cat.-no.: fataka 14 release date: November 17, 2016 https://f-a-t-a-k-a.bandcamp.com/album/tangle 1. – 3. Cluster 37:09 4. Tiefenschärfe 5:59 recorded on Februay 19th 2014 at Cafe Oto, London cover photo by Andy Moor liner notes by Nate Wooley "Tangle is the standout album of 2016 in my book, across the board. The ideas are flowing thick and fast, with everyone at the top of their game and perfectly in sync. There's a raw vitality to the performance, and the music is unabashed and direct in channeling relatively conventional lyricism. This is thrilling, peerless stuff, played with vivacity and animation. I was at the concert, and in my diary I jotted down a rare post-gig note that reads simply "!!!! f******k", but I'd forgotten it was quite this good." - Tim Owen | Dalston Sound | Nov. -

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

The New York City Jazz Record

BEST OF 2017 BEST OF 2017 BEST OF 2017 BEST OF 2017 BEST OF 2017 BEST OF 2017 THE NEW YORK CITY JAZZ RECORD BEST OF 2017 BEST OF 2017 BEST OF 2017 BEST OF 2017 BEST OF 2017 BEST OF 2017 ALBUMS OF THE YEAR CONCERTS OF THE YEAR MISCELLANEOUS CATEGORIES OF THE YEAR ANTHONY BRAXTON—Solo (Victoriaville) 2017 (Victo) BILL CHARLAP WITH CAROL SLOANE DARCY JAMES ARGUE’S SECRET SOCIETY PHILIPP GERSCHLAUER/DAVID FIUCZYNSKI— January 11th, Jazz Standard Dave Pietro, Rob Wilkerson, Chris Speed, John Ellis, UNEARTHED GEMS BOXED SETS TRIBUTES Mikrojazz: Neue Expressionistische Musik (RareNoise) Carl Maraghi, Seneca Black, Jonathan Powell, Matt Holman, ELLA FITZGERALD—Ella at Zardi’s (Verve) WILLEM BREUKER KOLLEKTIEF— TONY ALLEN—A Tribute to Art Blakey REGGIE NICHOLSON BRASS CONCEPT Nadje Noordhuis, Ingrid Jensen, Mike Fahie, Ryan Keberle, Out of the Box (BVHaast) and The Jazz Messengers (Blue Note) CHARLES LLOYD NEW QUARTET— Vincent Chancey, Nabate Isles, Jose Davila, Stafford Hunter Jacob Garchik, George Flynn, Sebastian Noelle, TUBBY HAYES QUINTET—Modes and Blues Passin’ Thru (Blue Note) February 4th, Sistas’ Place Carmen Staaf, Matt Clohesy, Jon Wikan (8th February 1964): Live at Ronnie Scott’s (Gearbox) ORNETTE COLEMAN—Celebrate Ornette (Song X) KIRK KNUFFKE—Cherryco (SteepleChase) THE NECKS—Unfold (Ideological Organ) January 6th, Winter Jazzfest, SubCulture STEVE LACY—Free For A Minute (Emanem) WILD BILL DAVISON— WADADA LEO SMITH— SAM NEWSOME/JEAN-MICHEL PILC— ED NEUMEISTER SOLO MIN XIAO-FEN/SATOSHI TAKEISHI THELONIOUS MONK— The Danish Sessions: -

The Piano Equation

Edward T. Cone Concert Series ARTIST-IN-RESIDENCE 2020–2021 Matthew Shipp The Piano Equation Saturday, November 21 2020 8:00 p.m. ET Virtual Concert, Live from Wolfensohn Hall V wo i T r n tu so osity S ea Institute for Advanced Study 2020–2021 Edward T. Cone Concert Series Saturday, November 21, 2020 8:00 p.m. ET MATTHEW SHIPP PROGRAM THE PIANO EQUATION Matthew Shipp Funding for this concert is provided by the Edward T. Cone Endowment and a grant from the PNC Foundation. ABOUT THE MUSIC David Lang writes: Over the summer I asked Matthew Shipp if he would like to play for us the music from his recent recording The Piano Equation. This album came out towards the beginning of the pandemic and I found myself listening to it over and over—its unhurried wandering and unpredictable changes of pace and energy made it a welcome, thoughtful accompaniment to the lockdown. My official COVID soundtrack. Matthew agreed, but he warned me that what he would play might not sound too much like what I had heard on the recording. This music is improvised, which means that it is different every time. And of course, that is one of the reasons why I am interested in sharing it on our season. We have been grouping concerts under the broad heading of ‘virtuosity’–how music can be designed so that we watch and hear a musical problem being overcome, right before our eyes and ears. Improvisation is a virtuosity all its own, a virtuosity of imagination, of flexibility, of spontaneity. -

Various the Wailing Ultimate - the Homestead Records Compilation Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various The Wailing Ultimate - The Homestead Records Compilation mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: The Wailing Ultimate - The Homestead Records Compilation Country: US Released: 1987 Style: Alternative Rock, Hardcore MP3 version RAR size: 1653 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1669 mb WMA version RAR size: 1295 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 180 Other Formats: AAC MP2 MMF APE MIDI MP4 AIFF Tracklist Hide Credits 1 –Dinosaur* Repulsion 3:06 White Elephant 2 –Volcano Suns 2:59 Producer – Lou Giordano Valley Of The Gwangi 3 –Phantom Tollbooth 3:15 Producer – Chris Xefos Sun God 4 –Squirrel Bait 2:49 Producer – Howie Gano Song Of The South 5 –Breaking Circus 2:30 Producer – Iain Burgess, Steve Björklund Il Duce 6 –Big Black 3:20 Producer – Iain Burgess The Well 7 –Salem 66 3:10 Producer – Ethan James Blood And Shaving Cream 8 –Death Of Samantha 3:07 Producer – Chris Burgess In A Glass House 9 –Antietam 4:11 Producer – Albert Garzon Fort Belvedere 10 –Live Skull 4:16 Producer – Martin Bisi I Remember 11 –Naked Raygun 2:23 Producer – Iain Burgess Don't Look Back 12 –The Reactions 3:28 Producer – Chris Burgess You're Not Patsy 13 –Big Dipper 2:34 Producer – Lou Giordano Letter To A Fanzine 14 –Great Plains 3:30 Producer – Don Howland, Michael Hummel Companies, etc. Copyright (c) – LSR Records, Inc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – LSR Records, Inc. Manufactured By – Laservideo Inc. – CI05726 Made By – Laservideo Inc. – CI05726 Notes © ℗ 1987 LSR Records, Inc. Printed in Canada CD Made in U.S.A. by LaserVideo, Inc. -

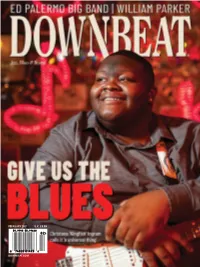

Downbeat.Com February 2021 U.K. £6.99

FEBRUARY 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2021 DOWNBEAT 1 FEBRUARY 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

![KUCI 88.9 FM [Spring 1991]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0742/kuci-88-9-fm-spring-1991-1230742.webp)

KUCI 88.9 FM [Spring 1991]

· ..... ~ , ·I ••• · . ....... ~,,\, . ) - . \ -' (X) ~ I, (X) ,N • -0/--- co • • • • • - ~ . 1'" ~ I . .,I/:..~ . a:: . .", • •· ·, ·• I ·t'· . .• ·· . ·· . .. •••• i ,,".' . .. /' • Day of Decency has come and' gone. It has been months since a couple of heads got together on the 3rd floor of gateway commons and decided what part they would play in a battle for what they thought was right. And nearly a month (perhaps two as you read this) since the dreams and the plan came together. OUtcome? Well. for one, I'm not really sure. I'dreallylike tothink that maybesome part of Meye opening" or MreactionaryseDiment" ocurred on account ofsomeone standingup and screaming MMy rights as a citizen are in danger." Jlut how can something like that be measured? To tell you the truth, I don't know, either. I wish I had played my part out. AJJ the decision to ban Minde~ency", "profanity", and "obcenity" from public radio stations 24 hours a day is being appealed. we must watch, not wait, and act. How? You can call 866-6868 and find out. Anyone of the folks on staff has' access to the information. any day of the week, at any time. Provided, of course, there is someone here (ahem!). We can give you names and addre~ses. fax and phone numb,..rs of organizations and individuals who need the assistance of people like yourself, or in some cases, would, and do, defy ~our opposition. AJJ someone who values creativity and its limitless bounds, and wonders at the different kinds of reactions it provi-ies. from rage to confusion to recognition, it Is important for me to posess the ability to think freely. -

Satoko Fujii in NYC Satokofujii.Com

power. The excitement stems from Aldana’s Never Be Another You” and melting tone on “The precociously mature lyric intelligence wedded to a Nearness Of You”. Worthy of mention, too, is di sensitive but restrained romanticism. The pared-down Martino’s lightly swinging work on “Moonglow” and format of her Crash Trio, with bassist Pablo Menares (a inspired pianistics on a bossa treatment of “Say It Isn’t fellow Chilean) and Cuban drummer Francisco Mela, So”. Other highlights are Kozlov’s arco introduction to gives her full freedom to explore, along with the “For All We Know” and Takahashi’s outstanding consequent responsibility to imply harmony in lieu of brushwork on “It Could Happen To You” and pulsing chording instruments. drumming on the Latin-ized “For All We Know”. The setlist contains two covers and tunes by each The ingredients in this album—a talented vocalist, Root of Things bandmember, mostly straightforward compositions five most able musicians and some of the best songs to Matthew Shipp Trio (Relative Pitch) with quirky twists, Mela’s catchy samba “Dear Joe” be found—all make for a most delicious treat. Enjoy! by Jeff Stockton probably the most memorable of the lot. But what jumps off the CD is the graceful, unbroken logic and For more information, visit barbaralevydaniels.com. Daniels Pianist Matthew Shipp is frequently labeled “cerebral” syntax of Aldana’s improvisations, a mix of extended is at Metropolitan Room Jun. 18th. See Calendar. and his playing is usually described using a math phrases and shorter exclamations, glued together with metaphor. Yet his musicianship with the David S. -

Crinew Music Re Uoft

CRINew Music Re u oft SEPTEMBER 11, 2000 ISSUE 682 VOL. 63 NO. 12 WWW.CMJ.COM MUST HEAR Universal/NIP3.com Trial Begins With its lawsuit against MP3.com set to go inent on the case. to trial on August 28, Universal Music Group, On August 22, MP3.com settled with Sony the only major label that has not reached aset- Music Entertainment. This left the Seagram- tlement with MP3.com, appears to be dragging owned UMG as the last holdout of the major its feet in trying to reach a settlement, accord- labels to settle with the online company, which ing to MP3.com's lead attorney. currently has on hold its My.MP3.com service "Universal has adifferent agenda. They fig- — the source for all the litigation. ure that since they are the last to settle, they can Like earlier settlements with Warner Music squeeze us," said Michael Rhodes of the firm Group, BMG and EMI, the Sony settlement cov- Cooley Godward LLP, the lead attorney for ers copyright infringements, as well as alicens- MP3.com. Universal officials declined to corn- ing agreement allowing (Continued on page 10) SHELLAC Soundbreak.com, RIAA Agree Jurassic-5, Dilated LOS AMIGOS INVIWITI3LES- On Webcasting Royalty Peoples Go By Soundbreak.com made a fast break, leaving the pack behind and making an agreement with the Recording Word Of Mouth Industry Association of America (RIAA) on aroyalty rate for After hitting the number one a [digital compulsory Webcast license]. No details of the spot on the CMJ Radio 200 and actual rate were released. -

Make It New: Reshaping Jazz in the 21St Century

Make It New RESHAPING JAZZ IN THE 21ST CENTURY Bill Beuttler Copyright © 2019 by Bill Beuttler Lever Press (leverpress.org) is a publisher of pathbreaking scholarship. Supported by a consortium of liberal arts institutions focused on, and renowned for, excellence in both research and teaching, our press is grounded on three essential commitments: to be a digitally native press, to be a peer- reviewed, open access press that charges no fees to either authors or their institutions, and to be a press aligned with the ethos and mission of liberal arts colleges. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, California, 94042, USA. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11469938 Print ISBN: 978-1-64315-005- 5 Open access ISBN: 978-1-64315-006- 2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944840 Published in the United States of America by Lever Press, in partnership with Amherst College Press and Michigan Publishing Contents Member Institution Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Jason Moran 21 2. Vijay Iyer 53 3. Rudresh Mahanthappa 93 4. The Bad Plus 117 5. Miguel Zenón 155 6. Anat Cohen 181 7. Robert Glasper 203 8. Esperanza Spalding 231 Epilogue 259 Interview Sources 271 Notes 277 Acknowledgments 291 Member Institution Acknowledgments Lever Press is a joint venture. This work was made possible by the generous sup- port of -

Donna-Singer.Com

preamble. Taken together, the three discs provide a drummer Hamid Drake together with Indian singer BOXED SET cross-section of some of Parker’s areas of work. More Sangeeta Bandyopadhyay, Senegalese singer Mola to the point, however, the set contains his symphonic Sylla (who also plays m’bira and donso n’goni) and debut and a thankful addition to his woefully small Dutch bass saxophonist Klaas Hekman. Across six body of work with singer Leena Conquest. tracks, they find and explore a number of overlapping Two song sets with Conquest occupy the first territories. At its best moments, the music comes disc. The half-hour suite For Fannie Lou Hamer, across as speaking deep truth, as if Bandyopadhyay dedicated to the Mississippi-born Civil Rights activist, the mystic and Sylla the griot were communicating was commissioned by The Kitchen and performed by through unknown tongues. Beautifully serene and the since-defunct Kitchen House Blend ensemble wildly free, it’s the best disc. (which—with reed players JD Parran and Sam A piece commissioned by the Polish National Furnace and trombonist Masahiko Kono—wasn’t Forum of Music for the NFM Symphony Orchestra For Those Who Are, Still such a stretch for Parker) in 2000. The second half, and performed at the 2013 Jazztopad Festival in William Parker (AUM Fidelity) Vermeer, is a nine-song cycle clocking in at 50 minutes Warsaw comprises the better part of the third disc and by Kurt Gottschalk and recorded at The Gallery Recording Studio in 2011 it’s here that Parker finds himself stretched behind his with Darryl Foster (saxophones), Eri Yamamoto means.