It's Not So Easy to Write a Dirty Novel" and Other Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lisa Gardner Prologue

LISA GARDNER PROLOGUE Who do you love? It’s a question anyone should be able to answer. A question that defines a life, creates a future, guides most minutes of one’s days. Simple, elegant, encompassing. Who do you love? He asked the question, and I felt the answer in the weight of my duty belt, the constrictive confines of my armored vest, the tight brim of my trooper’s hat, pulled low over my brow. I reached down slowly, my fingers just brushing the top of my Sig Sauer, holstered at my hip. “Who do you love?” he cried again, louder now, more insistent. My fingers bypassed my state- issued weapon, finding the black leather keeper that held my duty belt to my waist. The Velcro rasped loudly as I unfastened the first band, then the second, third, fourth. I worked the metal buckle, then my twenty pound duty belt, complete with my sidearm, Taser, and collapsible steel baton released from my waist and dangled in the space between us. “Don’t do this,” I whispered, one last shot at reason. He merely smiled. “Too little, too late.” “Where’s Sophie? What did you do?” “Belt. On the table. Now.” “No.” “GUN. On the table. NOW!” In response, I widened my stance, squaring off in the middle of the kitchen, duty belt still suspended from my left hand. Four years of my life, patrolling the highways of Massachusetts, swearing to defend and protect. I had training and experience on my side. © Lisa Gardner. All rights reserved. Page 1 www.LisaGardner.com LOVE YOU MORE LISA GARDNER I could go for my gun. -

View Playbill

MARCH 1–4, 2018 45TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON 2017/2018 Great Artists. Great Audiences. Hancher Performances. WORK LIGHT PRODUCTIONS PRESENTS BOOK BY BERRY GORDY MUSIC AND LYRICS FROM THE LEGENDARY MOTOWN CATALOG BASED UPON THE BOOK TO BE LOVED: MUSIC BY ARRANGEMENT WITH THE MUSIC, THE MAGIC, THE MEMORIES SONY/ATV MUSIC PUBLISHING OF MOTOWN BY BERRY GORDY MOTOWN® IS USED UNDER LICENSE FROM UMG RECORDINGS, INC. STARRING KENNETH MOSLEY TRENYCE JUSTIN REYNOLDS MATT MANUEL NICK ABBOTT TRACY BYRD KAI CALHOUN ARIELLE CROSBY ALEX HAIRSTON DEVIN HOLLOWAY QUIANA HOLMES KAYLA JENERSON MATTHEW KEATON EJ KING BRETT MICHAEL LOCKLEY JASMINE MASLANOVA-BROWN ROB MCCAFFREY TREY MCCOY ALIA MUNSCH ERICK PATRICK ERIC PETERS CHASE PHILLIPS ISAAC SAUNDERS JR. ERAN SCOGGINS AYLA STACKHOUSE NATE SUMMERS CARTREZE TUCKER DRE’ WOODS NAZARRIA WORKMAN SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN PROJECTION DESIGN DAVID KORINS EMILIO SOSA NATASHA KATZ PETER HYLENSKI DANIEL BRODIE HAIR AND WIG DESIGN COMPANY STAGE SUPERVISION GENERAL MANAGEMENT EXECUTIVE PRODUCER CHARLES G. LAPOINTE SARAH DIANE WORK LIGHT PRODUCTIONS NANSCI NEIMAN-LEGETTE CASTING PRODUCTION MANAGEMENT TOUR BOOKING AGENCY TOUR MARKETING AND PRESS WOJCIK | SEAY CASTING PORT CITY TECHNICAL THE BOOKING GROUP ALLIED TOURING RHYS WILLIAMS MOLLIE MANN ORCHESTRATIONS MUSIC DIRECTOR/CONDUCTOR DANCE MUSIC ARRANGEMENTS ADDITIONAL ARRANGEMENTS ETHAN POPP & BRYAN CROOK MATTHEW CROFT ZANE MARK BRYAN CROOK SCRIPT CONSULTANTS CREATIVE CONSULTANT DAVID GOLDSMITH & DICK SCANLAN CHRISTIE BURTON MUSIC SUPERVISION AND ARRANGEMENTS BY ETHAN POPP CHOREOGRAPHY RE-CREATED BY BRIAN HARLAN BROOKS ORIGINAL CHOREOGRAPHY BY PATRICIA WILCOX & WARREN ADAMS STAGED BY SCHELE WILLIAMS DIRECTED BY CHARLES RANDOLPH-WRIGHT ORIGNALLY PRODUCED BY KEVIN MCCOLLUM DOUG MORRIS AND BERRY GORDY The Temptations in MOTOWN THE MUSICAL. -

Popcorn Festival by Offering Free Popcorn (And Festival Information) in Front of the Bank on Weekends

u e ro a ___ ~~ Creater Valparaiso Chamber of Commerce , ORVILLE REUENBACHER RECOGNITION UAY SEPTEMBER 15, 1979 O'1(/ "18"110 /)OJJC l:'il81U til' (/iI,.~"1) ~:I)e(/ 1:'$ '119 I,. '901) '811", "e ilil " at NORTHERN INDIANA BANK we're excited about popcorn and this First Annual Event SEPTEMBER 15, 1979 Pictured are Executive Vice President Les Robinson and Marketing Director John Schnurlein with Andy and Jenni Stritof with the Bank's Old Fashioned Popcorn Wagon which was used to promote the Popcorn Festival by offering Free Popcorn (and Festival Information) in front of the Bank on weekends. Andy and Jenni popped and gave away over 300 pounds of Redenbacher Gourmet Popping Corn during the 9 week period! The Willing Bank became involved in Valparaiso's First Annual Popcorn Festival in its early planning stages. Our whole staff was swept up in the excitement of the gala event and became involved in many committees and activities. We are proud to have assisted the Greater Valparaiso Chamber of Commerce in help ing direct national attention to Valparaiso during the First Valparaiso Popcorn Festival. We look forward to participating in many more! 7he 'WLllmg CJ3ank • • • Member Federal Deposit I NORTHERN INDIANA BANK .,s Insurance Corporation N...I ~\ and •• and TRUST COMPANY Greater Valparaiso ~ Chamber of Commerce J VALPARAISO. KOUTS. BURNS HARBOR. HEBRON Great r Val' aral 0 Chamber of Commerco September 15, 1979 WELCOME TO OUR CITY: The Greater Valparaiso Chamber of Commerce wishes to give you a warm, sincere welcome to "Valparaiso's First Annual Popcorn Festival." We are proud of the many people who have worked long hours to make this Festival possible today. -

T O D a Y ' S T E a S

PUNCH UP YOUR NEWSLETTER AND PUMP UP YOUR READERSHIP Copy and paste content into your publication. All photos and images are copyright-free and may be reproduced without prior permission. [email protected] MON D A Y , JUNE 3 Today we spill the beans … For the second consecutive year, EASER buttered popcorn is America’s favorite jelly bean flavor. According to sales data collected by an online candy retailer, buttered popcorn is the favorite in seven states ─ more than any other flavor. Rounding out the top five jelly beans nationally T are cinnamon, black licorice, cherry and watermelon. And if you’re a fan of the chili mango flavor, you should know that its sales don’t add up to a hill of beans. We’re like a kid in a candy store when we see all the great stories in today’s edition of company news. S Source: Associated Press ’ Y TUES D A Y , J U N E 4 You won’t hear a peep out of us about today’s report … Police investigating a disturbance in Loerrach, Germany, discovered a man arguing with a parrot. A neighbor called to report loud shouting from a next-door apartment that had been going on for hours. Officers arrived on the scene to find an argument taking place between a 22-year-old man and a parrot. The man said he had been annoyed with the bird, which belonged to his girlfriend. The parrot responded to his shouting by squawking back. Officials ordered the man to pay a small fine for the disturbance. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist - Human Metallica (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace "Adagio" From The New World Symphony Antonín Dvorák (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew "Ah Hello...You Make Trouble For Me?" Broadway (I Know) I'm Losing You The Temptations "All Right, Let's Start Those Trucks"/Honey Bun Broadway (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (Reprise) (I Still Long To Hold You ) Now And Then Reba McEntire "C" Is For Cookie Kids - Sesame Street (I Wanna Give You) Devotion Nomad Feat. MC "H.I.S." Slacks (Radio Spot) Jay And The Mikee Freedom Americans Nomad Featuring MC "Heart Wounds" No. 1 From "Elegiac Melodies", Op. 34 Grieg Mikee Freedom "Hello, Is That A New American Song?" Broadway (I Want To Take You) Higher Sly Stone "Heroes" David Bowie (If You Want It) Do It Yourself (12'') Gloria Gaynor "Heroes" (Single Version) David Bowie (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here! Shania Twain "It Is My Great Pleasure To Bring You Our Skipper" Broadway (I'll Be Glad When You're Dead) You Rascal, You Louis Armstrong "One Waits So Long For What Is Good" Broadway (I'll Be With You) In Apple Blossom Time Z:\MUSIC\Andrews "Say, Is That A Boar's Tooth Bracelet On Your Wrist?" Broadway Sisters With The Glenn Miller Orchestra "So Tell Us Nellie, What Did Old Ironbelly Want?" Broadway "So When You Joined The Navy" Broadway (I'll Give You) Money Peter Frampton "Spring" From The Four Seasons Vivaldi (I'm Always Touched By Your) Presence Dear Blondie "Summer" - Finale From The Four Seasons Antonio Vivaldi (I'm Getting) Corns For My Country Z:\MUSIC\Andrews Sisters With The Glenn "Surprise" Symphony No. -

Tributaries 2014

3 . TTributaries Mission Statement Tributaries is a student-produced literary and arts journal published at Indiana University East that seeks to publish invigorating and multifaceted fiction, nonfiction, poetry, essays, and art. Our modus operandi is to do two things: Showcase the talents of writers and artists whose work feeds into a universal body of creative genius while also paying tribute to the greats who have inspired us. We accept submissions on a rolling basis and publish on an annual schedule. Each edition is edited during the fall and winter months, which culminates in an awards ceremony and release party in the spring. Awards are given to the best pieces submitted in all categories. Tributaries is edited by undergraduate students at Indiana University East. 4 TRIBUTARIES Table of Contents Fiction “Salty” 2014 Prize for Fiction Richard Goss 8 “Warm Feet in a Cold Creek” Richard Goss 11 “Time Can Heal” Chelsy Nichols 15 “Draguignan” 2014 First Runner-up Brandi Masterson 19 “Finding my Sunshine” Andrea Sebring 22 “An Unexpected Discovery” Betty Osthoff 26 Creative Nonfiction “The Family Mythos” 2014 First Runner-up Joshua Lykins 34 “Anna” Jenn Sroka 37 “Bully” 2014 Prize for Creative Nonfiction Jenn Sroka 45 “Living on a Prayer” Tahna Moore 47 Poetry “Big Brother” Kathryn Yohey 58 “Lullaby Lost” Stephanie Beckner 59 “Seasons” John Mahaffey 60 “Procrastinator’s Lament” Christopher Knox 62 “Sleeping in Sleeping Bags” Tie: 2014 Prize for Poetry Christopher Rodgers 63 “Liar” Tahna Moore 64 “Love Affair with Rain” Shore Crawford 65 “Fade” Hannah Clark 66 “Wrought by Red” Tie: 2014 Prize for Poetry S. -

At the Movies

THE TM 911 Franklin Street Weekly Newspaper Michigan City, IN 46360 Volume 30, Number 45 Thursday, November 13, 2014 At the Movies MICHIGAN CITY ONCE WAS HOME TO GRAND VENUES By William Halliar Editor’s note — This week, we resume our series exploring the history behind key locations along Michigan City’s North End. Happy children mug for the camera at the Liberty Theater in 1948. Photo from “Michigan City: The First 150 Years.” Old movie houses of Memories of an after- Franklin Street’s heyday. noon at the movies. Their names bring back Lido Tivoli Liberty Motion pictures have memories of so many hours been part of the fabric of spent with family and our lives for more than 100 friends, of sharing stories years. We grew up under of thrilling adventures, exploration and love. Eating their spell, as did our parents. We can’t escape their hot buttered popcorn and holding hands with your infl uence in our culture. best girl, laughing and sobbing with your favorite What is this great fascination? It is all about hero or heroine. Continued on Page 2 THE Page 2 November 13, 2014 THE 911 Franklin Street • Michigan City, IN 46360 219/879-0088 • FAX 219/879-8070 In Case Of Emergency, Dial e-mail: News/Articles - [email protected] email: Classifieds - [email protected] http://www.thebeacher.com/ PRINTED WITH Published and Printed by TM Trademark of American Soybean Association THE BEACHER BUSINESS PRINTERS Delivered weekly, free of charge to Birch Tree Farms, Duneland Beach, Grand Beach, Hidden 911 Shores, Long Beach, Michiana Shores, Michiana MI and Shoreland Hills. -

Crazy Ex-Girlfriend (2015-2019) Published May 10Th, 2020 Listen Here at Themcelroy.Family

Still Buffering 211: Crazy Ex-Girlfriend (2015-2019) Published May 10th, 2020 Listen here at TheMcElroy.family [theme music plays] Rileigh: Hello, and welcome to Still Buffering, a cross-generational guide to the culture that made us. I am Rileigh Smirl. Sydnee: I'm Sydnee McElroy. Teylor: And I'm Teylor Smirl. Sydnee: Uh, I understand from Twitter that I am supposed to as for a vibe check now? Is that what I saw? Rileigh: Oh no. [laughs] Yes. Sydnee: Uh, tweeted by you? Rileigh: I made—okay. So, I don't know if this has happened to you while in your Animal Crossing games. Welcome to another episode about Animal Crossing. Um… Sydnee: It's not really. Rileigh: It's, not but… Teylor: Yeah. Sydnee: [laughs] Rileigh: I wish. Um, we—[laughs] one of my villagers said, "I feel like my catchphrase is getting pretty stale. Do you have a suggestion for a new one?" And immediately thought, "I want… this rhinoceros to ask me for a vibe check every time we speak." So I made her catchphrase "Vibe check?" And then something happened, and it has been passed among all of my villagers, so now every single villager on my island, whenever I'm talking to them, ends their phrase with, "Vibe check?" Sydnee: [laughs quietly] Teylor: [laughs] Rileigh: And it is very good! [laughs] Teylor: That's pretty cute. Sydnee: What does that—does that just mean, like, "How are you?" Rileigh: How are your vibes? Vibe check. Sydnee: I've never heard that. Rileigh: It's a… oh. -

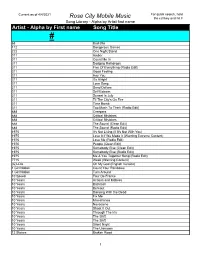

Alpha by First Name Song Title

Current as of 4/4/2021 For quick search, hold Rose City Mobile Music the ctrl key and hit F Song Library - Alpha by Artist first name Artist - Alpha by First name Song Title # 68 Bad Bite 112 Dangerous Games 222 One Night Stand 311 Amber 311 Count Me In 311 Dodging Raindrops 311 Five Of Everything (Radio Edit) 311 Good Feeling 311 Hey You 311 It's Alright 311 Love Song 311 Sand Dollars 311 Self Esteem 311 Sunset In July 311 Til The City's On Fire 311 Time Bomb 311 Too Much To Think (Radio Edit) 888 Creepers 888 Critical Mistakes 888 Critical Mistakes 888 The Sound (Clean Edit) 888 The Sound (Radio Edit) 1975 It's Not Living (If It's Not With You) 1975 Love It If We Made It (Warning Extreme Content) 1975 Love Me (Radio Edit) 1975 People (Clean Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Clean Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Radio Edit) 1975 Me & You Together Song (Radio Edit) 7715 Week (Warning Content) (G)I-Dle Oh My God (English Version) 1 Girl Nation Count Your Rainbows 1 Girl Nation Turn Around 10 Speed Tour De France 10 Years Actions and Motives 10 Years Backlash 10 Years Burnout 10 Years Dancing With the Dead 10 Years Fix Me 10 Years Miscellanea 10 Years Novacaine 10 Years Shoot It Out 10 Years Through The Iris 10 Years The Shift 10 Years The Shift 10 Years Silent Night 10 Years The Unknown 12 Stones Broken Road 1 Current as of 4/4/2021 For quick search, hold Rose City Mobile Music the ctrl key and hit F Song Library - Alpha by Artist first name Artist - Alpha by First name Song Title 12 Stones Bulletproof 12 Stones Psycho 12 Stones We Are One 16 Frames Back Again 16 Second Stare Ballad of Billy Rose 16 Second Stare Bonnie and Clyde 16 Second Stare Gasoline 16 Second Stare The Grinch (Radio Edit ) 1975. -

Brewers Association Draught Beer Quality Manual Fourth Edition

DRAUGHT BEER QUALITY MANUAL FOURTH EDITION Prepared by the Technical Committee of the Brewers Association BREWERS ASSOCIATION DRAUGHT BEER QUALITY MANUAL FOURTH EDITION Prepared by the Technical Committee of the Brewers Association Brewers Publications® A Division of the Brewers Association PO Box 1679, Boulder, Colorado 80306-1679 BrewersAssociation.org BrewersPublications.com © Copyright 2019 by Brewers AssociationSM All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission of the publisher. Neither the authors, editors, nor the publisher assume any responsibility for the use or misuse of information contained in this book. Proudly printed in the United States of America. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 ISBN-13: 978-1-938469-60-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Brewers Association. Title: Draught beer quality manual / prepared by the Technical Committee of the Brewers Association. Description: Fourth edition. | Boulder, Colorado : Brewers Publications, a Division of the Brewers Association, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018045113 (print) | LCCN 2018046073 (ebook) | ISBN 9781938469619 (E-book) | ISBN 9781938469602 Subjects: LCSH: Brewing--Handbooks, manuals, etc. | Beer--Handbooks, manuals, etc. | Brewing--Equipment and supplies. | Brewing industry--United States. Classification: LCC TP577 (ebook) | LCC TP577 .D73 2019 (print) | DDC 663/.3--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018045113 Publisher: Kristi Switzer Technical Editor: Ernie Jimenez Copyediting: Iain Cox Proofreading: Iain Cox Indexing: Doug Easton Art Direction, Cover, and Interior Design: Jason Smith Production: Justin Petersen Cover Photo: Luke Trautwein Photo © Christine Celmins Photography Celmins © Christine Photo TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ...................................................................vii Shanks ........................................................... -

Senioritis: the Rock Musical

SENIORITIS: THE ROCK MUSICAL Book and lyrics by Joe Janes and Pete Ficht Music by Pete Ficht c/o Pete Ficht 63047 Marsh Orchid Dr. Bend, OR 97701 503-866-1760 [email protected] www.senioritisthemusical.com 2 Cast of Characters JACK MILLER, 18, high school senior, funny, smart, popular, but with a mean streak LAWRENCE JACKSON, 18, high school senior, athletic, nice, and cooler than Jack JENNY WELLER, 17, high school junior, warm, intelligent, and indulgent of Jack GURTZ, 17, high school senior, druggie burnout, but has integrity “FUCK DUDE” (aka Nan), 16, high school junior, sweet stoner “hippie chick” ALEX LEE, 16, high school junior, nerdy and bookish, and looks up to Jack BANDLEADER, early 20s, smartass hipster PRINCIPAL HUNT, 40s (not Hispanic), hard-working and burned out, but hopeful COACH YANARELLA, 30s, good-looking, macho, dim MR. IMMEL, 50s, teacher, overweight and picked on by students and staff LOIS, 40s, 7-ELEVEN clerk, socially awkward and easily victimized GIL, 50s, cook/owner of Dessert Café ARLENE, 50s, a waitress SALLY, 18, waitress GRAHAM, 60s, cafe customer MARNIE, 60s, cafe customer OTTO, 20s, a prisoner MARCO, 60s, janitor TAGGERT, 50s, prison administrator RAMIREZ, 40s, prison guard OFFICER DELONG, 50s, cop OFFICER WALKER, 30s, cop MARGE, 30s, school security guard Voiceovers/Off stage: Talk Radio Host, District Attorney, Victim, “America’s Most Wanted” Host, News Anchor, Charles, Loretta, Judge SENIORITIS: THE ROCK MUSICAL by Joe Janes and Pete Ficht 3 Note that this show can easily be performed with 13 actors (9 male, 4 female), if the following roles are played by single actors: Fuck Dude, Sally Hunt, Marnie Lois, Arlene, Security Guard Coach, Officer DeLong Immel, Graham, Marco Gil, Ramirez, Officer Walker Taggert, Otto SENIORITIS: THE ROCK MUSICAL by Joe Janes and Pete Ficht 4 The setting is a city in the Pacific Northwest, in the late 1990s. -

Truman Plaza, Germany

TRUMAN PLAZA, GERMANY by Marc Svetov I. Grandmother 4 Boston – Berlin 8 Pearl Harbor 14 They Can Tell By Our Noses 21 Fathers, Artists 26 This is Your Great Adventure! 31 Communal Apartment 35 Vodka and Righteousness 38 Red Balloon 42 Feliks Mayer 47 Hobo and Rabbi 51 Vicious Circles 58 Grandmother 64 II. PX – Post Exchange 68 Yoga 74 … You Name It, The Germans Had It 77 I’ll Kill Them! 83 This Drama Has No End 86 Farewell 89 Hunger 91 Grandmother 94 Kung Fu 96 Diamonds … 98 … And Marlboros 102 Transcendence 104 Conversations with Rudolf Hess 106 Grandmother 110 Chicago 113 Nudniks 118 Pumpkin Seeds 123 There Are Days Like These 128 Mihai And Wife 136 TRUMAN PLAZA | Marc Svetov | www.TransatlanticHabit.com 2 III. Andrews Barracks 140 Making Peace 145 It’s Different 151 Buttons 156 Hermits 161 Walkie‐Talkie 165 Grandmother 167 A Crummy Guy 171 To Find Millie 173 So Nice and Gray 177 I Swear By Apollo the Physician 182 Little Drummer Boy 186 Grandmother 190 Rebels? Idiots! 195 … And By Asklepios, Hygeia, and Panacea 198 How Green Was My Valley 204 Why? Why, Howard? 209 A Nut! An American! 212 … And By All the Gods and Goddesses 214 Things Were Not Going Well 217 … And Call Them to Witness 219 Feliks Meyer 221 Asphyxiation 223 In the Hospital 225 Arrival 228 TRUMAN PLAZA | Marc Svetov | www.TransatlanticHabit.com 3 Jonah got along in the belly of the whale, Daniel in the lion’s den, But I know a guy who didn’t try to get along And he won’t get a chance again… That’s all she wrote, “Dear John! I’ll send your saddle home.” “Dear John”, recorded by Hank Williams (Ritter/Gass) Grandmother “My dear Alan,” my Grandma Bess wrote me a month after I had arrived in Berlin, using her blue ballpoint, “God, how I miss you and wish you were here.