Boroughbridge 1322

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Milby Grange Boroughbridge a New Home

Milby Grange Boroughbridge A new home. The start of a whole new chapter for you and your family. And for us, the part of our job where bricks and mortar becomes a place filled with activity and dreams and fun and love. We put a huge amount of care into the houses we build, but the story’s not finished until we match them up with the right people. So, once you’ve chosen a Miller home, we’ll do everything we can to make the rest of the process easy, even enjoyable. From the moment you make your decision until you’ve settled happily in, we’ll be there to help. Living in Boroughbridge 02 Welcome home 06 Floor plans 08 How to find us 40 Milby Grange 01 Plot Information Tolkien N See Page 08 Darwin See Page 10 Darwin DA See Page 12 Malory See Page 14 SUDS POS Buchan See Page 16 110 101 109 Buchan DA 110 110 102 103 See Page 18 109 108 115 107 Pumping 114 108 108 Station 113 106 103 Ashbery 112 111 107 105 See Page 20 111 104 56 115 106 Repton 114 105 57 112113 104 See Page 22 99 100 58 123 111 116 99 62 POS 122 117 98 100 61 Tressell 120 97 63 119 63 64 60 See Page 24 116 96 121 118 117 96 99 98 64 59 POS 120 65 Mitford 118 97 59 127 119 95 See Page 26 96 66 65 51 94 50 126 128 49 48 67 V 66 Buttermere 95 47 94 52 V 128 46 See Page 28 88 89 91 68 V 129 68 67 45 90 44 124 9091 49 50 53 Jura Development 48 124 87 89 92 43 47 125 93 46 See Page 30 By Others 130 92 88 69 45 39 38 54 93 70 44 40 Shakespeare 145 87 72 71 41 40 131 86 75 74 73 43 55 See Page 32 69 86 42 42 144 35 Affordable 132 41 72 85 72 85 84 73 VP 74 75 75 V Housing 134 VP 133 35 V 143 133 84 36 V 34 POS 143 134 83 37 82 142 VP 83 33 VP 135 136 82 33 36 135 78 76 29 37 142 136 79 32 81 80 30 29 137 77 31 30 VP 139 138 77 32 30 31 31 141 79 141 LEAP 140 26 26 25 25 140 27 27 27 28 21 20 21 19 18 17 16 28 15 14 13 13 26 VP 24 25 VP 9 8 10 23 3 7 22 The artist’s impressions 19 20 21 16 17 18 (computer-generated 13 14 15 graphics) have been 12 2 10 11 prepared for illustrative 7 8 9 5 6 purposes and are 4 indicative only. -

Land at the Old Quarry Monk Fryston Offers Invited

Land at The Old Quarry Monk Fryston Offers Invited Land/Potential Development Site – Public Notice – We act on behalf of the Parish Council / vendors in the sale of this approximately 2/3 acre site within the development area of Monk Fryston. Any interested parties are invited to submit best and final offers (conditional or unconditional) in writing (in a sealed envelope marked ‘Quarry Land, Monk Fryston’ & your name) to the selling agents before the 1st June 2014. Stephensons Estate Agents, 43 Gowthorpe, Selby, YO8 4HE, telephone 01757 706707. • Potential Development Site • Subject to Planning Permission • Approximately 2/3 Acre • Sought After Village Selby 01757 706707 www.stephensons4property.co.uk Estate Agents Chartered Surveyors Auctioneers Land at The Old Quarry, Monk Fryston Potential development site (subject to planning permission). The site extends to approximately 2/3 acre and forms part of a former quarry, located in this much sought after village of Monk Fryston. With shared access off the Main Street/Leeds Road. The successful developer/purchaser may wish to consider the possibility of a further access off Lumby Lane/Abbeystone Way, which may be available via a third party (contact details can be provided by the selling agent). The site is conveniently located for easy vehicular access to the A1/M62 motorway network and commuting to many nearby regional centres such as York, Leeds, Doncaster and Hull etc. TO VIEW LOCAL AUTHORITY By appointment with the agents Selby office. Selby District Council Civic Centre LOCATION Portholme Road Located on the edge of this much sought after village of Monk Selby Fryston and being conveniently located for access to the A1/M62 YO8 4SB motorway network and commuting to many regional centres like Telephone 01757 705101 Leeds, Wakefield, Doncaster, Tadcaster, York and Selby etc. -

The Early History of Man's Activities in the Quernmore Area

I Contrebis 2000 The Early History of Man's Activities in the Quernmore Area. Phil Hudson Introduction This paper hopes to provide a chronological outline of the events which were important in creating the landscape changes in the Quernmore forest area. There was movement into the area by prehistoric man and some further incursions in the Anglo- Saxon and the Norse periods leading to Saxon estates and settled agricultural villages by the time of the Norman Conquest. These villages and estates were taken over by the Normans, and were held of the King, as recorded in Domesday. The Post-Nonnan conquest new lessees made some dramatic changes and later emparked, assarted and enclosed several areas of the forest. This resulted in small estates, farms and vaccaries being founded over the next four hundred years until these enclosed areas were sold off by the Crown putting them into private hands. Finally there was total enclosure of the remaining commons by the 1817 Award. The area around Lancaster and Quernmore appears to have been occupied by man for several thousand years, and there is evidence in the forest landscape of prehistoric and Romano-British occupation sites. These can be seen as relict features and have been mapped as part of my on-going study of the area. (see Maps 1 & 2). Some of this field evidence can be supported by archaeological excavation work, recorded sites and artif.act finds. For prehistoric occupation in the district random finds include: mesolithic flints,l polished stone itxe heads at Heysham;'worked flints at Galgate (SD 4827 5526), Catshaw and Haythomthwaite; stone axe and hammer heads found in Quernmore during the construction of the Thirlmere pipeline c1890;3 a Neolithic bowl, Mortlake type, found in Lancaster,o a Bronze Age boat burial,s at SD 5423 5735: similar date fragments of cinerary urn on Lancaster Moor,6 and several others discovered in Lancaster during building works c1840-1900.7 Several Romano-British sites have been mapped along with finds of rotary quems from the same period and associated artifacts. -

Minutes 13 November 2017

KIRBY HILL AND DISTRICT PARISH COUNCIL (incorporating Kirby Hill, Milby, Thornton Bridge, Humberton & Ellenthorpe parishes) MINUTES of the parish council meeting held at 7.00 pm on 13 November 2017, in the Coronation Hall, Milby (Notice having been given). PRESENT: Cllrs Lawson (Chairman), Hick, Jones, Lister, Merson, Smailes, Widdows, Wilkinson, DCllr Brown, NYCCllr Windass (from 7.15pm) and Martin Rae (Clerk). Public: Gareth Owens and Thomas Wilkinson 1. APOLOGIES for absence: None 2. CODE OF CONDUCT/REGISTER OF INTERESTS: Cllr Wilkinson 8b&f - as tenant farmer of land subject to applications, Cllr Merson 4d, Cllr Lister 7c 3. MINUTES of the meeting of 11 September 2017, having been distributed previously were accepted as a true record and duly signed by the Chairman. Matters arising - none Item 6b. taken at this time to allow DCllr Brown to go on to another meeting. See below. 4. FINANCE Clerk reported: a) Balance at 13 Nov 2017 £5,103.07 (Anticipated carryover 31 March £3,500) b) Coronation Hall rent of room – payment agreed c) AA Foster Grass cutting – 2nd half year + 3 extra cuts £415.00 Payment agreed d) Martlets Food/Agricultural Services (Cllr Merson) fuel/equip expenses for 7 cuts on Milby Island £210+VAT payment agreed e) Royal British Legion wreath donation (S137) £35.00 paid f) Boroughbridge Community Care donation (S137) £30.00 paid g) Kirby Hill United Benefice Magazine donation (S137) £30.00 paid h) HMRC (for July/August/Sept) £97.38 paid i) HBC Precept 2nd half year £2,000 rec’d j) Northern Electric wayleave £49.38 rec’d k) Langthorpe Parish Council – Milby Island project contribution £300.00 rec’d 5. -

Agenda for the Meeting Below

BOROUGHBRIDGE TOWN COUNCIL 1 HALL SQUARE, BOROUGHBRIDGE, NORTH YORKSHIRE YO51 9AN www.boroughbridge.org.uk email: [email protected] John Nichols TownTel: Clerk 01423 322956 30th December 2021 Dear Councillors, I hereby summon you to the following meeting of BOROUGHBRIDGE TOWN COUNCIL to be held by Zoom. PLANNING COMMITTEE MEETING Tuesday 5th January at 6:00pm. Please see the Agenda for the meeting below: John Nichols Clerk to the Council Note: Members are reminded of the need to consider whether they have any pecuniary or non-pecuniary interests to declare on any of the items on this agenda and, if so, of the need to explain the reason(s) why. Queries should be addressed to the Monitoring Officer Ms Jennifer Norton 01423 556036. PLANNING COMMITTEE MEETING AGENDA – Tuesday 5th January 6.00pm 1. Apologies. 2. Declarations of Interest in items on the Agenda. 3. Parish Council Notifications for consultation received since the last Planning Committee Meeting a) 6.64.808.FUL 20/04250/FUL Erection of 2 No. yurts and associated decking and hot tubs. Erection of associated WC, Shower and Kitchen unit. LOCATION: Grange Farm Cottage Main Street Minskip YO51 9HZ https://uniformonline.harrogate.gov.uk/online- applications/applicationDetails.do?activeTab=summary&keyVal=QJ0YLHHYG9L00 1 | P a g e b) 6.64.810.FUL 20/04415/FUL Erection of single storey conservatory. LOCATION: 3 Hazeldene Fold Minskip York North Yorkshire YO51 9PH https://uniformonline.harrogate.gov.uk/online- applications/applicationDetails.do?activeTab=summary&keyVal=QJLHMNHY0DM00 c) 6.64.223.AM.TPO 20/04572/TPO Crown lift to 3m to provide pedestrian clearance, and crown reduce by 3m, to 1no. -

Heritage at Risk Register

CASTLE HOWARD MAUSOLEUM Castle Howard Estate, Ryedale, North Yorkshire The Mausoleum, by Hawksmoor, 1729-42, and modelled on the tomb of Metella, is a major feature of the Howardian Hills. Situated on a bluff east of Castle Howard. The columns were repaired with a grant in the 1980s. The entablature and bastions continue to decay. Much of the damage is due to rusting cramps. The staircase balustrade is collapsing. 304 HERITAGE AT RISK YORKSHIRE & THE HUMBER 305 Y&H HERITAGE AT RISK 2008 Of the 176 entries on the baseline 1999 Yorkshire and the Humber buildings at risk register, 91(52%) have now been removed. Although this is 6% higher than the regional average for 2008, our rate of progress is slowing. Of the five entries removed this year, only one was on the 1999 register. This is because the core of buildings remaining from the 1999 register are either scheduled monuments with no obvious use, or buildings with a problematic future that require a strategic re-think to provide a viable solution. Despite these problems, we are continuing to work with owners, local authorities, trusts and other funding bodies to try to secure the long-term future of these buildings and structures. Just over half (52%) of the regional grants budget (almost £500,000) was offered to eleven buildings at risk in the last financial year. There are four new entries this year: in North Yorkshire, St Leonard’s Church at Sand Hutton, and in West Yorkshire, Hopton Congregational Church in Mirfield,Westwood Mills at Linthwaite, and Stank Hall near Leeds.This gives a total of 122 Grade I and II* listed buildings and scheduled monuments at risk entries on the Yorkshire and the Humber register. -

The Story of a Man Called Daltone

- The Story of a Man called Daltone - “A semi-fictional tale about my Dalton family, with history and some true facts told; or what may have been” This story starts out as a fictional piece that tries to tell about the beginnings of my Dalton family. We can never know how far back in time this Dalton line started, but I have started this when the Celtic tribes inhabited Britain many yeas ago. Later on in the narrative, you will read factual information I and other Dalton researchers have found and published with much embellishment. There also is a lot of old English history that I have copied that are in the public domain. From this fictional tale we continue down to a man by the name of le Sieur de Dalton, who is my first documented ancestor, then there is a short history about each successive descendant of my Dalton direct line, with others, down to myself, Garth Rodney Dalton; (my birth name) Most of this later material was copied from my research of my Dalton roots. If you like to read about early British history; Celtic, Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Normans, Knight's, Kings, English, American and family history, then this is the book for you! Some of you will say i am full of it but remember this, “What may have been!” Give it up you knaves! Researched, complied, formated, indexed, wrote, edited, copied, copy-written, misspelled and filed by Rodney G. Dalton in the comfort of his easy chair at 1111 N – 2000 W Farr West, Utah in the United States of America in the Twenty First-Century A.D. -

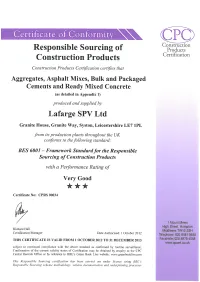

BES 6001 Lafarge SPV Schedule

Appendix 1 Lafarge SPV Ltd – Certificate No CPRS 00034 (Issue No 1) Product Unit Address Postcode Aggregates Willington Quarry Bedford Road, Couple, Bedford, Bedfordshire MK44 3PG Aggregates Dowlow Quarry Dowlow Quarry, Sterndale Moor, Buxton, Derbyshire SK17 9QF Aggregates Ashbury Bessamer Street, West Gorton, Manchester M11 2NW Aggregates Briton Ferry Wharf Old Iron Works, Briton Ferry Wharf, Neath, Swansea SA11 2LN Asphalt Mixes Wivenhoe Plant Alresford Road, Wivenhoe, Colchester, Essex CO7 9JX Packed and Bulk Cements Hope Works Hope Valley, Derbyshire S33 6RP Packed and Bulk Cements Dewsbury Depot Bretton Street, Saville Town, Dewsbury, West Yorkshire WF12 9BJ Packed and Bulk Cements Theale Depot Wigmore Lane, Theale, Berkshire RG7 5HH Ready Mixed Concrete Aldermaston Youngs Industrial Estate, Paices Hill, Aldermaston, Berkshire RG7 4PG Ready Mixed Concrete Alrewas Yewtree House, Croxall Road, Alrewas, Burton-on-Trent, Staffordshire DE13 7DL Ready Mixed Concrete Ashbury Ashbury Railhead, Bessemer Street, Gorton, Manchester M11 2NW Ready Mixed Concrete Ashfield Maun Valley Industrial Estate, Station Road, Sutton-in-Ashfield, Nottinghamshire NG17 5GS Ready Mixed Concrete Aylesbury Griffin Lane, Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire HP19 3BP Ready Mixed Concrete Banbury Railstone Terminal, Waterworks Road, off Hennef Way, Banbury, Oxfordshire OX16 3JJ Ready Mixed Concrete Barnsley Wombwell Lane, Stairfoot, Barnsley, South Yorkshire S70 3NS Ready Mixed Concrete Bedlington Barrington Industrial Estate, Barrington Road, Bedlington Station, Northumberland -

House of Pilkington

House of Pilkington History/Background Our Pilkington Pedigree Pilkington Appendix The Pilkington family has its origins in the ancient township of Pilkington in the historic county of Lancashire, England. After about 1405 the family seat was Stand Old Hall which was built to replace Old Hall in Pilkington. The new hall was built on high land overlooking Pilkington's medieval deer park. Stand Old Hall was replaced by Stand Hall to the south in 1515 after the Pilkingtons were dispossessed. Stand Old Hall became a barn. It is possible that Sir Thomas Pilkington had permission to “embattle” his manor house in 1470 building a stone tower. It was a ruin by the 1950s and demolished in the early 1960s. The Pilkington name is taken from the manor of Pilkington in Prestwich, Lancashire. The Pilkington arms consist of an argent cross patonce voided gules. The Pilkington crest has a mower with his scythe and has a legend that an ancestor of the family, being sought at the time of the Norman Conquest, disguised himself as a mower + and escaped. Ye Olde Man & Scythe Inn in Bolton derives its name from the reaper using a scythe on the family crest. The crest was first recorded on a seal from 1424. Throughout the county there were a number of branches of the family, including those from Rivington Hall, Rivington near Chorley and from Windle Hall near St Helens, founders of the Pilkington glass manufacturers. The first known is Alexander de Pilkington, who was recorded in 1200 and held the manor in 1212. In 1212 Pilkingtons held Rivington in Bolton-le-Moors, which became the home of a junior branch of the family. -

Isurium Brigantum

Isurium Brigantum an archaeological survey of Roman Aldborough The authors and publisher wish to thank the following individuals and organisations for their help with this Isurium Brigantum publication: Historic England an archaeological survey of Roman Aldborough Society of Antiquaries of London Thriplow Charitable Trust Faculty of Classics and the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge Chris and Jan Martins Rose Ferraby and Martin Millett with contributions by Jason Lucas, James Lyall, Jess Ogden, Dominic Powlesland, Lieven Verdonck and Lacey Wallace Research Report of the Society of Antiquaries of London No. 81 For RWS Norfolk ‒ RF Contents First published 2020 by The Society of Antiquaries of London Burlington House List of figures vii Piccadilly Preface x London W1J 0BE Acknowledgements xi Summary xii www.sal.org.uk Résumé xiii © The Society of Antiquaries of London 2020 Zusammenfassung xiv Notes on referencing and archives xv ISBN: 978 0 8543 1301 3 British Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background to this study 1 Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data 1.2 Geographical setting 2 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the 1.3 Historical background 2 Library of Congress, Washington DC 1.4 Previous inferences on urban origins 6 The moral rights of Rose Ferraby, Martin Millett, Jason Lucas, 1.5 Textual evidence 7 James Lyall, Jess Ogden, Dominic Powlesland, Lieven 1.6 History of the town 7 Verdonck and Lacey Wallace to be identified as the authors of 1.7 Previous archaeological work 8 this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Lantern Slides Illustrating Zoology, Botany, Geology, Astronomy

CATALOGUES ISSUED! A—Microscope Slides. B—Microscopes and Accessories. C—Collecting Apparatus D—Models, Specimens and Diagrams— Botanical, Zoological, Geological. E—Lantfrn Slides (Chiefly Natural History). F—Optical Lanterns and Accessories. S—Chemicals, Stains and Reagents. T—Physical and Chemical Apparatus (Id Preparation). U—Photographic Apparatus and Materials. FLATTERS & GARNETT Ltd. 309 OXFORD ROAD - MANCHESTER Fourth Edition November, 1924 This Catalogue cancels all previous issues LANTERN SLIDES illustrating Zoology Birds, Insects and Plants Botany in Nature Geology Plant Associations Astronomy Protective Resemblance Textile Fibres Pond Life and Sea and Shore Life Machinery Prepared by FLATTERS k GARNETT, LTD Telephone : 309 Oxford Road CITY 6533 {opposite the University) Telegrams : ” “ Slides, Manchester MANCHESTER Hours of Business: 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. Saturdays 1 o’clock Other times by appointment CATALOGUE “E” 1924. Cancelling all Previous Issues Note to Fourth Edition. In presenting this New Edition we wish to point out to our clients that our entire collection of Negatives has been re-arranged and we have removed from the Catalogue such slides as appeared to be redundant, and also those for which there is little demand. Several new Sections have been added, and, in many cases, old photographs have been replaced by better ones. STOCK SLIDES. Although we hold large stocks of plain slides it frequently happens during the busy Season that particular slides desired have to be made after receipt of the order. Good notice should, therefore, be given. TONED SLIDES.—Most stock slides may be had toned an artistic shade of brown at an extra cost of 6d. -

Robin Hood and the Coterel Gang

Robin Hood Memories of the Coterel Gang Ron Catterall Copyright © 2007,2008 Ron Catterall All Rights Reserved. The right of Ron Catterall to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Ron Catterall 1 Robin Hood 1. Introduction Lythe and listin, gentilmen, That be of frebore blode; I shall you tel of a gode yeman, His name was Robyn Hode. —Anonymous, ca.1350, A Gest of Robyn Hode 1-4 It would be very difficult, if not impossible, to find a member of the large Cotterell family who had never heard of Robin Hood, but how many Cotterells are aware that the activities of the Coterel Gang in Sherwood Forest in the early fourteenth century may well have been the original from which the Robin Hood legend derived. I think we all must have absorbed in childhood the links between Robin Hood, the Sheriff of Nottingham and Sherwood Forest, but attempts to identify Robin with a known historical character have never been generally accepted. The traditional picture comes from the work of Anthony Munday, a contemporary of William Shakespeare, in the period 1598-1601. The titles of his work contain almost all the elements of the Robin Hood we know today: “The Downfall of Robert, Earle of Huntington, Afterward called Robin Hood of merrie Sherwodde: with his love to chaste Matilda, the Lord Fitzwaters Daughter, afterwarde his faire Maide Marian” and “The Death of Robert, Earle of Huntington. Otherwise called Robin Hood of merrie Sherwodde: with the lamentable Tragedie of chaste Matilda, his faire maid Marian, poysoned at Dunmowe by King John”.