The Bauhaus: Evolution of an Idea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bauhaus and Weimar Modernism

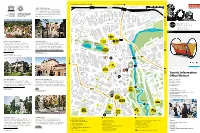

Buchenwald Memorial, Ettersburg Castle Sömmerda (B7 / B85) 100 m weimar UNESCO World Heritage 500 m Culture City of Europe The Bauhaus and its sites in Weimar and Dessau have been on the UNESCO list of World Heritage since 1996. There are three objects in Weimar: the main building of the Bauhaus University Weimar, the former School of Applied Arts and the Haus Am Horn. Tiefurt Mansion deutschEnglish Harry-Graf-Kessler-Str. 10 5 Tiefurt Mansion Bauhaus-Universität Weimar Nietzsche Archive B Jorge-Semprùn-Platz a Oskar-Schlemmer-Str. d The building ensemble by Henry van de Velde was Friedrich Nietzsche spent the last years of his life at H e Stèphane- r 1 s revolutionary in terms of architecture at the turn of the “Villa Silberblick”. His sister established the Nietzsche Archive f Hessel-Platz e l d century. These Art School buildings became the venue here after his death and had the interior and furnishings e r S where the State Bauhaus was founded in 1919, making designed by Henry van de Velde. The current exhibition is t r a ß “Weimar” and the “Bauhaus” landmarks in the history of entitled “Kampf um Nietzsche” (“Dispute about Nietzsche”). e modern architecture. Humboldtstrasse 36 13 Mon, Wed to Sun 2pm – 5pm Geschwister-Scholl-Strasse 2 Mon to Fri 10am – 6pm | Sat & Sun 10am – 4pm Über dem Kegeltor C o u d r a y s t Erfurt (B7) r a ß e Berkaer Bahnhof 8 CRADLE, DESIGN: PETER KELER, 1922 © KLASSIK STIFTUNG WEIMAR 17 Jena (B7) 3 Tourist Information Office Weimar Haus Hohe Pappeln Weimar Municipal Museum 20 16 Markt 10, 99423 Weimar The Belgian architect Henry van de Velde, the artistic The permanent exhibition of the Municipal Museum presents Tel + 49 (0) 3643 745 0 advisor of the grand duchy, built this house for his family of “Democracy from Weimar. -

Nachlass Der Bauhäusler Hinnerk Und Lou Scheper Für Berlin Gesichert

Pressemeldung Nachlass der Bauhäusler Hinnerk und Lou Scheper für Berlin gesichert Lotto-Stiftung Berlin ermöglicht Ankauf der Arbeiten und Dokumente von Hinnerk und Lou Scheper durch das Bauhaus-Archiv / Museum für Gestaltung Mit Unterstützung der Lotto-Stiftung kann der Nachlass des Künstlerehepaares Hinnerk und Lou Scheper in Berlin gehalten werden. Mit einer Förderung in Höhe von 1,185 Mio. Euro ermöglicht die Lotto-Stiftung dem Bauhaus-Archiv / Museum für Gestaltung in Berlin den Erwerb des umfassen- den Erbes von Hinnerk und Lou Scheper und sichert es für Berlin. In seiner dritten Sitzung 2016 hatte der Stiftungsrat der Lotto-Stiftung Berlin unter Vorsitz des Regierenden Bürgermeisters Michael Müller am 5. Oktober 2016 insgesamt 18,5 Millionen Euro ausgeschüttet. Berlin, 06.10.16. Die Künstler Hinnerk und Lou Scheper haben das Bauhaus entscheidend geprägt. Darü- ber hinaus hatten sie einen entscheidenden Anteil an der künstlerischen und denkmalpflegerischen Ent- wicklung Berlins in den Nachkriegsjahren. Zum einzigartigen Nachlass des Paares gehören Farbgestal- tungen, Zeichnungen, Druckgrafiken, Fotografien, Möbel, Designobjekte, Dokumente und Korresponden- zen sowie eine umfassende Bibliothek mit seltenen Ausstellungskatalogen, Broschüren und Zeitschriften der 1920er-Jahre. „Dank der großzügigen Förderung der Lotto-Stiftung Berlin wird es uns möglich, den großartigen Nachlass von Hinnerk und Lou Scheper – zwei der bedeutendsten Vertreter des Bauhauses – dauerhaft für das Bauhaus-Archiv und damit für die Forschung und für die Öffentlichkeit zu sichern“, freut sich Dr. Annemarie Jaeggi, Direktorin des Bauhaus-Archiv / Museum für Gestaltung. „Wir danken allen Unterstützern für die große Wertschätzung unserer Arbeit.“ Der Nachlass Hinnerk und Lou Scheper Sowohl Hinnerk als auch Lou Scheper zählen zu zentralen Persönlichkeiten am Bauhaus. -

Feininger Klee Bauhaus Feininger Klee Bauhaus

feininger klee bauhaus feininger klee bauhaus 01.05.2019 — 18.01.2020 New York Dortmund Wien Inhalt contents 06 Lyonel Feininger – vom Karikaturisten zum Bauhausmeister Wolfgang Büche 07 Lyonel Feininger —from Caricaturist to Bauhaus Master Wolfgang Büche 22 werke Lyonel Feininger 22 works by Lyonel Feininger 60 lyonel feininger über paul klee 61 lyonel feininger on paul klee 70 werke Paul Klee 70 works by paul klee 84 biografien 84 biographies 92 ausgestellte werke 92 exhibited works 104 impressum Die Bauhausmeister auf dem Dach des Bauhauses in Dessau anlässlich der Eröffnung am 4. und 5. Dezember 1926 The Bauhaus Masters on the roof of the Bauhaus in Dessau at its opening on December 4 & 5, 1926 104 imprint Lyonel Feininger 04 05 Lyonel Feininger Lyonel Feininger – vom Karikaturisten —from Caricaturist zum Bauhausmeister to Bauhaus Master Wolfgang Büche Wolfgang Büche Als Lyonel Feininger im Mai 1919 als der erstberufene Bau- When Lyonel Feininger was sitting on the train to Weimar hausmeister im Zug nach Weimar saß, gehörte er in Deutsch- in May 1919 on his way to become one of the first Bauhaus land bereits zu den arrivierten Malern. Es gab Sammler masters appointed to teach at the school, he was already seiner Werke und Museen begannen sich für sein Schaffen a well-established painter in Germany. There were already zu interessieren. Mit seiner ersten Einzelausstellung 1917 in a few collectors of his work, and museums were starting to der Galerie Der Sturm in Berlin war er endgültig als einer der take an interest in him. His first solo exhibition at the Galerie Protagonisten der Moderne in Deutschland eingeführt. -

Irrational / Rational Production-Surrealism Vs The

MIT 4.602, Modern Art and Mass Culture (HASS-D/CI) Spring 2012 Professor Caroline A. Jones Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section. Department of Architecture Lecture 14 PRODUCTION AND (COMMODITY) FETISH: key dates: Lecture 14: Irrational Rational Production: Bauhaus 1919 (Sur)realism vs. the Bauhaus Idea Surrealism 1924 “The ultimate, if distant, objective of the Bauhaus is the Einheitskunstwerk- the great building in which there will be no boundary between monumental and decorative art.” -Walter Gropius (Bauhaus Manifesto. 1919) “Little by little the contradictory signs of servitude and revolt reveal themselves in all things.” - the Surrealist. Georges Bataille, 1929 “Bauhaus is the name of an artistic inspiration.” - Asger Jom, writing to Max Bill, 1954. “Bauhaus is not the name of an artistic inspiration, but the meaning of a movement that represents a well-defined doctrine.” -Bill to Jorn. 1954 “If Bauhaus is not the name of an artistic inspiration. it is the name of a doctrine without inspiration - that is to say. dead.'” - Jom 's riposte. 1954 “Issues of surrealist heterogeneity will be resolved around the semiological functions of photography rather than the formal properties … of style.” -Rosalind Krauss, 1981 I. Review: Duchamp, Readymade as fetish? Fountain by “R. Mutt,” 1917 II. Rational Production: the Bauhaus, 1919 - 1933 A. What's in a name? (Bauhaus” was a neologism coined by its founder, Walter Gropius, after medieval “Bauhütte”) The prehistory of Reform. B. Walter Gropius's goal: “to create a new guild of craftsmen, without the class distinctions which raise an arrogant barrier between craftstnan and artist. [...] painting and sculpture rising to heaven out of the hands of a million craftsmen, the crystal symbol of the new faith of the future.” C. -

Dessau: Höhepunkt Der Ästhetik in Der Industrie-Epoche - Das Bauhaus Und Seine Bauten

• • Dessau: Höhepunkt der Ästhetik in der Industrie-Epoche - das Bauhaus und seine Bauten Weitreichender Zusammenhang. In Bei der Wiedereröffnung des Bau Dessau hatte in der zweiten Hälfte des hauses in den 80er Jahren wird der Zu 18. Jahrhundert ein aufgeklärter Klein sammenhang zwischen Gartenreich und fürst eine vielbewunderte Gesellschafts- Bauhaus erneut diskutiert. Der Begriff Utopie geschaffen: eine Synthese von „Industrielles Gartenreich“ entsteht. Empfindung und Vernunft, sozialem und In diesem Diskurs ergeben sich Ver kulturellem Verhalten, Nutzen und Schön bindungen zur IBA-Berlin / Strategien heit. für Kreuzberg (Hardt-Walther Hämer) Davon ist vieles mental lebendig, als und der IB A-Emscher Park im Ruhrgebiet das Bauhaus 1925 nach Dessau kommt. (Karl Ganser, Gerhard Seitmann). Der ge meinsame Faden ist die Begleitung des in dustriellen Struktur-Wandels: in einer Synthese von Potential-Denken und Ge stalten. In diesem Kontext entwickelt die Landesregierung 1996 eine Strategie: es entsteht eine Agentur zur Entwicklung der regionalen Struktur. Verknüpft mit dem Gedanken an die Expo Hannover heißt dieses umfangreiche Projekt-Paket (S. 596): Expo 2000 Sachsen-Anhalt. Das Drama der Vorge schichte: Aufstieg und Fall des Bauhauses in Weimar Walter Gropius gründet 1919 das Bau haus. Er ist seit 1910 Mitglied im Deut schen Werkbund - ebenso wie der künst lerische Berater der Zukunfts-Industrie, des Elektrizitäts-Konzerns AEG, Peter Behrens. Behrens entwickelte aus indu striellen Materialien und Prozessen eine Lyonei Feininger: Kathedrale des Sozialismus eigene Ästhetik der Industrie. 1908 bis (1919, Holzschnitt) 1910 war Gropius im Atelier von Beh- rens tätig, vor allem als Architekt. Er sog tag. Die „Weimarer Künstlerschaft“ for dort neue Ideen ein. -

Northern Gothic: Werner Haftmann's German

documenta studies #11 December 2020 NANNE BUURMAN Northern Gothic: Werner Haftmann’s German Lessons, or A Ghost (Hi)Story of Abstraction This essay by the documenta and exhibition scholar Nanne Buurman I See documenta: Curating the History of the Present, ed. by Nanne Buurman and Dorothee Richter, special traces the discursive tropes of nationalist art history in narratives on issue, OnCurating, no. 13 (June 2017). German pre- and postwar modernism. In Buurman’s “Ghost (Hi)Story of Abstraction” we encounter specters from the past who swept their connections to Nazism under the rug after 1945, but could not get rid of them. She shows how they haunt art history, theory, the German feuilleton, and even the critical German postwar literature. The editor of documenta studies, which we founded together with Carina Herring and Ina Wudtke in 2018, follows these ghosts from the history of German art and probes historical continuities across the decades flanking World War II, which she brings to the fore even where they still remain implicit. Buurman, who also coedited the volume documenta: Curating the History of the Present (2017),I thus uses her own contribution to documenta studies to call attention to the ongoing relevance of these historical issues for our contemporary practices. Let’s consider the Nazi exhibition of so-called Degenerate Art, presented in various German cities between 1937 and 1941, which is often regarded as documenta’s negative foil. To briefly recall the facts: The exhibition brought together more than 650 works by important artists of its time, with the sole aim of stigmatizing them and placing them in the context of the Nazis’ antisemitic racial ideology. -

Paul Klee Centennial: Prints and Transfer Drawings

Paul Klee Centennial PRINTS AND TRANSFER PR AWTM1S jk f i-Vioo JJBRARYJ ' Museumcf !,; &:n : Rail h lee Centennial PRINTS AND TRANSFER DRAWINGS January8 - April3, 1979 TheMuseum of ModernArt, New York /hclui/C tit? ft i j iSj T> Trusteesof The Museumof ModernArt WilliamS. Paley,Chairman of the Board;Gardner Cowles, Mrs.Bliss Parkinson, David Rockefeller, ViceChairmen; Mrs. John D. Rockefeller3rd, President;Mrs. Frank Y. Larkin,Donald B. Marron, JohnParkinson III, Vice Presidents; John ParkinsonIII, Treasurer; Mrs. L. vA.Auchincloss, EdwardLarrabee Barnes, Alfred H. Barr,Jr.,* Mrs.Armand P. Bartos,Gordon Bunshaft, Shirley C. Burden,William A.M. Burden, Thomas S. Carroll, FrankT. Cary, IvanChermayeff, Mrs. C. Douglas Dillon,Gianluigi Gabetti, PaulGottlieb, George HeardHamilton, Wallace K. Harrison,*Mrs. Walter Hochschild,*Mrs. John R. Jakobson,Philip Johnson, Mrs.Frank Y. Larkin,Ronald S. Lauder,John L. Loeb, RanaldH. Macdonald,*Mrs. G. Macculloch Miller,*J. IrwinMiller,* S. I. Newhouse,Jr., RichardE. Oldenburg,Peter G. Peterson,Gifford Phillips,Nelson A. Rockefeller,*Mrs. Albrecht Saalfield,Mrs. Wolfgang Schoenborn,* Martin E. Segal,Mrs. Bertram Smith, James Thrall Soby,* Mrs.Alfred R. Stern,Mrs. Donald B. Straus,Walter N. Thayer,R.L.B. Tobin, EdwardM.M. Warburg,* Mrs.Clifton R. Wharton,Jr., MonroeWheeler,* John HayWhitney* * HonoraryTrustee Ex Officio EdwardI. Koch, Mayorof the Cityof New York; HarrisonJ. Goldin,Comptroller of the Cityof New York. Frontcover: VulgarComedy (1922) Copyright©1979, TheMuseum of ModernArt 11 West53 Street,New -

The Bauhaus 1 / 70

GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS 1 / 70 The Bauhaus 1 Art and Technology, A New Unity 3 2 The Bauhaus Workshops 13 3 Origins 26 4 Weimar 45 5 Dessau 57 6 Berlin 68 © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS 2 / 70 © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE ARTS & CRAFTS MOVEMENT 3 / 70 1919–1933 Art and Technology, A New Unity A German design school where ideas from all advanced art and design movements were explored, combined, and applied to the problems of functional design and machine production. © Kevin Woodland, 2020 Joost Schmidt, Exhibition Poster, 1923 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS / Art and TechnoLogy, A New Unity 4 / 70 1919–1933 The Bauhaus Twentieth-century furniture, architecture, product design, and graphics were shaped by the work of its faculty and students, and a modern design aesthetic emerged. MEGGS © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS / Art and TechnoLogy, A New Unity 5 / 70 1919–1933 The Bauhaus Ideas from all advanced art and design movements were explored, combined, and applied to the problems of functional design and machine production. MEGGS • The Arts & Crafts: Applied arts, craftsmanship, workshops, apprenticeship • Art Nouveau: Removal of ornament, application of form • Futurism: Typographic freedom • Dadaism: Wit, spontaneity, theoretical exploration • Constructivism: Design for the greater good • De Stijl: Reduction, simplification, refinement © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS / Art and TechnoLogy, A New Unity 6 / 70 1919–1933 -

Cosmic Being from Theory to Practice Mohammed Mustafa Bachelor's

Cosmic Being From theory to practice Mohammed Mustafa Bachelor’s thesis August 2018 Degree programme Media and Arts ABSTRACT Tampereen ammattikorkeakoulu Tampere University of Applied Sciences Media and Arts Mohammed Mustafa Cosmic Being: From theory to practice Bachelor's thesis, 28 pages, appendices 25 pages August 2018 Art theory has long been recognized as playing an important role in understanding art practice and building up critical thinking that can so valuably influence an artist’s prac- tice. Art theory is perceived as the nature of art, the definition and statement for any art movement. This thesis focuses on Bauhaus theatre as an art theory. The case study then explores how to transfer that theory into a fine art practice. The implementation of this practice was divided into two parts, one focused on photography and the other on graphic de- sign. From Chapter Five to Chapter Eight, the discussion of this case study, Cosmic be- ing: from theory to practice, is presented. This study drew largely on the analysis of various works of literature including but not limited to the following: The Letters and Diaries of Oskar Schlemmer (1990) edited by Tut Schlemmer; The Theatre of the Bauhaus (Gropius & Wensinger 1979), a collection of essays written by Oskar Schlemmer (Schlemmer 1979), Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, and Farkas Molnár; and Dance the Bauhaus (2016) edited by Torsten Blume. Bauhaus, with its fascinating mechanization of the stage and the human figures thereon, has not disappeared; its influence exists in theatres and performances across the world, most notably in the use of video techniques in the theatre, and the use of technology and multimedia as integral elements of stage performances. -

Editor's Note

Editor’s Note Dear readers, Although Bauhaus is relevant throughout history, this German school of art remains an open issue in art, architecture, design, and communication, addressing the following question: To what extent is Bauhaus even possible nowadays? Thus, this was our question for the Art Style Magazine's Bauhaus Special Edition. Therefore, in an attempt to showcase some of the most important issues so our readers can attain a broad notion of this German school's legacy, our Editorial Team has been working diligently and participated in several significant events, talks, round tables, and exhibitions. The opening festival and construction of the Bauhaus Museum in Weimar, for example, offered a great view of the importance of the Bauhaus. Above all, in the sense of arts and crafts in connection with industry, this school outlined a relationship of teaching design from product development, consumption to the changes of living together. Recently, the so-called "Fishfilet scandal" – an attempt to prevent a live event by a German rock band – was an important facet in the discussion that the Bauhaus still plays a significant role in the political scene. As artists and politicians said, the ban on concerts means a "terrifying history" for Bauhaus-Dessau. A month ago, we heard news from a round table, and artistic interventions under the title "How political is the Bauhaus?". These talks had taken place in the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (House of World Cultures) in Berlin on January 19, 2019. It was part of the opening festival of Bauhaus's centenary and supported by the Senate Department for Culture and Europe. -

Getty Research Institute | June 11 – October 13, 2019

Getty Research Institute | June 11 – October 13, 2019 OBJECT LIST Founding the Bauhaus Programm des Staatlichen Bauhauses in Weimar (Program of the State Bauhaus in Weimar) 1919 Walter Gropius (German, 1883–1969), author Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871–1956), illustrator Letterpress and woodcut on paper 850513 Idee und Aufbau des Staatlichen Bauhauses Weimar (Idea and structure of the State Bauhaus Weimar) Munich: Bauhausverlag, 1923 Walter Gropius (German, 1883–1969), author Letterpress on paper 850513 Bauhaus Seal 1919 Peter Röhl (German, 1890–1975) Relief print From Walter Gropius, Satzungen Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar (Weimar, January 1921) 850513 Bauhaus Seal Oskar Schlemmer (German, 1888–1943) Lithograph From Walter Gropius, Satzungen Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar (Weimar, July 1922) 850513 Diagram of the Bauhaus Curriculum Walter Gropius (German, 1883–1969) Lithograph From Walter Gropius, Satzungen Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar (Weimar, July 1922) 850513 1 The Getty Research Institute 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100, Los Angeles, CA 90049 www.getty.edu German Expressionism and the Bauhaus Brochure for Arbeitsrat für Kunst Berlin (Workers’ Council for Art Berlin) 1919 Max Pechstein (German, 1881–1955) Woodcut 840131 Sketch of Majolica Cathedral 1920 Hans Poelzig (German, 1869–1936) Colored pencil and crayon on tracing paper 870640 Frühlicht Fall 1921 Bruno Taut (German, 1880–1938), editor Letterpress 84-S222.no1 Hochhaus (Skyscraper) Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (German, 1886–1969) Offset lithograph From Frühlicht, no. 4 (Summer 1922): pp. 122–23 84-S222.no4 Ausstellungsbau in Glas mit Tageslichtkino (Exhibition building in glass with daylight cinema) Bruno Taut (German, 1880–1938) Offset lithographs From Frühlicht, no. 4 (Summer 1922): pp. -

UNSEEN WORKS of the EUROPEAN AVANT-GARDE An

Press Release July 2020 Mitzi Mina | [email protected] | Melica Khansari | [email protected] | Matthew Floris | [email protected] | +44 (0) 207 293 6000 UNSEEN WORKS OF THE EUROPEAN AVANT-GARDE An Outstanding Family Collection Assembled with Dedication Over Four Decades To Be Offered at Sotheby’s London this July Over 40 Paintings, Sculpture & Works on Paper Led by a Rare Cubist Work by Léger & an Intimate Picasso Portrait of his Secret Lover Marie-Thérèse Pablo Picasso | Fernand Léger | Alberto Giacometti | Wassily Kandinsky | Lyonel Feininger | August Macke | Alexej von Jawlensky | Jacques Lipchitz | Marc Chagall | Henry Moore | Henri Laurens | Jean Arp | Albert Gleizes Helena Newman, Worldwide Head of Sotheby’s Impressionist & Modern Art Department, said: “Put together with passion and enjoyed over many years, this private collection encapsulates exactly what collectors long for – quality and rarity in works that can be, and have been, lived with and loved. Unified by the breadth and depth of art from across Europe, it offers seldom seen works from the pinnacle of the Avant-Garde, from the figurative to the abstract. At its core is an exceptionally beautiful 1931 portrait of Picasso’s lover, Marie-Thérèse, an intimate glimpse into their early days together when the love between the artist and his most important muse was still a secret from the world.” The first decades of the twentieth century would change the course of art history for ever. This treasure-trove from a private collection – little known and rarely seen – spans the remarkable period, telling its story through the leading protagonists, from Fernand Léger, Pablo Picasso and Alberto Giacometti to Wassily Kandinsky, Lyonel Feininger and Alexej von Jawlensky.