Prime Minister Mahmoud Abbas Is Scheduled to A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statement of H.E. President Mahmoud Abbas President of the State of Palestine UN General Assembly General Debate of the 75Th Session 25 September 2020

Statement of H.E. President Mahmoud Abbas President of the State of Palestine UN General Assembly General Debate of the 75th Session 25 September 2020 In the name of God, the Merciful H.E. Mr. Volkan Bozkir, President of the General Assembly H.E. Mr. António Guterres, Secretary General Ladies and Gentlemen, Heads and Members of delegations, I wondered while preparing this statement what more could I tell you, after all that I have said in previous statements, about the perpetual tragedy and suffering being endured by my people – which the world is witness to daily – and about their legitimate aspirations – which are yet to be fulfilled – to freedom, independence and human dignity, as enjoyed by the peoples of the world. Until when, ladies and gentlemen, will the question of Palestine remain without a just solution as enshrined in United Nations resolutions? Until when will the Palestinian people remain under Israeli occupation and will the question of millions of Palestine refugees remain without a just solution in accordance with what the United Nations has determined over 70 years ago? Ladies and Gentlemen, The Palestinian people have been present in their homeland, Palestine, the land of their ancestors, for over 6000 years, and they will continue living on this land, steadfast in the face of occupation, aggression and the disappointments and betrayals, until the fulfilment of their rights. Despite all they have endured and continue to endure, despite the unjust blockade that targets our national decision, we will not kneel or surrender and we will not deviate from our fundamental positions, and we shall overcome, God willing. -

Briefing Notes 23 September 2013

Information Centre Asylum and Migration Briefing Notes 23 September 2013 Afghanistan Attack on state representative On 15.09.13, a senior female criminal police officer was shot at by unknown gunmen in southern Helmand province. One day later, she died from her wounds. Her female predecessor had been assassinated in the same way. Women comprise no more than one percent of all Afghan police officers. They and their families are regularly threatened by Islamists. On 18.09.13. the head of the independent electoral commission for northern Kunduz province was shot dead by Taliban insurgents. After the beginning of the preparations for the presidential elections, the Taliban had announced attacks on election officials and organisers. Increase of attacks on aid organisation staff The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reports a sharp increase in attacks on staff members of humanitarian and medical aid organisations. A total of 25 incidents have been reported, with eight people losing their lives. Most of the attacks on medical organisations and their workers have occurred in the eastern parts of the country, namely in Nangarhar, Laghman, Logar and Kunar provinces as well as in northern Balkh province. Other aspects of the security situation According to information provided by the German Federal Armed Forces, operations led by Afghan security forces have been carried out since 04.09.13 in the northern provinces of Badakhshan and Kunduz, aiming at pushing the rebels out of the area and securing their own mobility. On 18.09.13, a police unit ran into an ambush of the Taliban in northeastern Badakhshan province (Wardooj district), with approx. -

Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas: Overview of Internal and External Challenges

Order Code RS22047 Updated March 1, 2005 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas: Overview of Internal and External Challenges Aaron D. Pina Analyst in Middle East Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Summary On January 15, 2005, Mahmoud Abbas (a.k.a. Abu Mazen) was sworn in as President of the Palestinian Authority (PA). Many believe that the Abbas victory marks the end of an autocratic era dominated by the late Yasir Arafat and the increased possibility of improved prospects for Israeli-Palestinian peace. This report details Abbas’s policy platform and potential challenges he may face from within and without the Palestinian political landscape as power-sharing becomes a reality. Domestically, Abbas must address violent anti-occupation elements, calls for economic, judicial, and security reform, as well as a paralyzed economy. Externally, Abbas faces multiple obstacles in creating a viable Palestinian state based on a secure peace with Israel. To accomplish this, Abbas must address the requirements of the ‘Road Map,’ Palestinian violence toward Israel, and final status issues, such as Jerusalem, refugees, and political borders. For a more detailed analysis see CRS Report RS21965, Arafat’s Succession, by Clyde Mark and CRS Report RS21235, The PLO and its Factions, by Kenneth Katzman. This report will be updated as necessary. Palestinian Centers of Power Fatah. Under Arafat, Fatah became the most prominent political party in the Palestinian territories. The leading political body within Fatah is the Central Committee (CC), elected by the general membership. Fatah’s Revolutionary Council (RC) parallels the CC as a decision-making body and does not exclude armed resistance as an option. -

Is Israel Facing War with Hizbullah and Syria? by David Schenker Published April 2010 Vol

Is Israel Facing War with Hizbullah and Syria? by David Schenker Published April 2010 Vol. 9, No. 22 6 April 2010 • Concerns about Israeli hostilities with Hizbullah are nothing new, but based on recent pronouncements from Syria, if the situation degenerates, fighting could take on a regional dimension not seen since 1973. • On February 26, Syrian President Bashar Assad hosted Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Hizbullah leader Hassan Nasrallah in Damascus. Afterward, Hizbullah's online magazine Al Intiqad suggested that war with Israel was on the horizon. • Raising tensions further are reports that Syria has provided Hizbullah with the advanced, Russian-made, shoulder-fired, Igla-S anti-aircraft missile, which could inhibit Israeli air operations over Lebanon in a future conflict. The transfer of this equipment had previously been defined by Israeli officials as a "red line." • In the summer of 2006, Syria sat on the sidelines as Hizbullah fought Israel to a standstill. After the war, Assad, who during the fighting received public assurances from then-Prime Minister Olmert that Syria would not be targeted, took credit for the "divine victory." • Damascus' support for "resistance" was on full display at the Arab Summit in Libya in late March 2010, where Assad urged Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas to abandon U.S.-supported negotiations and "take up arms against Israel." • After years of diplomatic isolation, Damascus has finally broken the code to Europe, and appears to be on the verge of doing so with the Obama administration as well. Currently, Syria appears to be in a position where it can cultivate its ties with the West without sacrificing its support for terrorism. -

Critical Policy Brief Number 4/2021

Critical Policy Brief Number 4/2021 The challenges that forced the Fatah movement to postpone the general elections Ala’a Lahlouh and Waleed Ladadweh Strategic Analysis Unit July 2021 Alaa Lahluh: Researcher at the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research, holds a master’s degree in contemporary Arab studies from Birzeit University, graduated in 2003. He has many research activities in the areas of democratic transformation, accountability and integrity in the security sector and the Palestinian national movement and participated in preparing the Palestine Report on the Arab Security Scale and a report on The State of Reform in the Arab World "The Arab Democracy Barometer" ". Among his publications is "Youth Participation in the Local Authorities Elections 2017", Bethlehem, Student Forum, December 2019, under publication, and “The Problem of Distributing Military Ranks to Workers in the Palestinian Security Forces”, The Civil Forum for Enhancing Good Governance in the Security Sector, November 2019, and “The Migration of Palestinian Christians: Risks and Threats", Ramallah, Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research, 2019, under publication. Walid Ladadweh: Master of Arts in Sociology and Head of the Survey Research Unit at the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research (Ramallah, Palestine) and a member of the Advisory Council for Palestinian Statistics from 2005-2008. He completed his master’s studies at Birzeit University in Palestine in 2003. He also completed several training courses in the field of research, the last of which was training courses at the University of Michigan in the United States on survey research techniques in 2010. He supervised more than 70 opinion polls in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, and has vast experience in providing proposals, writing reports, preparing, and presenting educational materials, managing field work, and analyzing data using various analysis programs. -

Reviving the Stalled Reconstruction of Gaza

Policy Briefing August 2017 Still in ruins: Reviving the stalled reconstruction of Gaza Sultan Barakat and Firas Masri Still in ruins: Reviving the stalled reconstruction of Gaza Sultan Barakat and Firas Masri The Brookings Institution is a private non-profit organization. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides to any supporter is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment and the analysis and recommendations are not determined by any donation. Copyright © 2017 Brookings Institution BROOKINGS INSTITUTION 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. www.brookings.edu BROOKINGS DOHA CENTER Saha 43, Building 63, West Bay, Doha, Qatar www.brookings.edu/doha Still in ruins: Reviving the stalled reconstruction of Gaza Sultan Barakat and Firas Masri1 INTRODUCTION Israelis and Palestinians seems out of reach, the humanitarian problems posed by the Three years have passed since the conclusion substandard living conditions in Gaza require of the latest military assault on the Gaza Strip. the attention of international actors associated Most of the Palestinian enclave still lies in ruin. with the peace process. If the living conditions Many Gazans continue to lack permanent in Gaza do not improve in the near future, the housing, living in shelters and other forms of region will inevitably experience another round temporary accommodation. -

S/PV.8717 the Situation in the Middle East, Including the Palestinian Question 11/02/2020

United Nations S/ PV.8717 Security Council Provisional Seventy-fifth year 8717th meeting Tuesday, 11 February 2020, 10 a.m. New York President: Mr. Goffin ..................................... (Belgium) Members: China ......................................... Mr. Zhang Jun Dominican Republic ............................. Mr. Singer Weisinger Estonia ........................................ Mr. Jürgenson France ........................................ Mr. De Rivière Germany ...................................... Mr. Schulz Indonesia. Mr. Djani Niger ......................................... Mr. Aougi Russian Federation ............................... Mr. Nebenzia Saint Vincent and the Grenadines ................... Ms. King South Africa ................................... Mr. Mabhongo Tunisia ........................................ Mr. Ladeb United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland .. Ms. Pierce United States of America .......................... Mrs. Craft Viet Nam ...................................... Mr. Dang Agenda The situation in the Middle East, including the Palestinian question This record contains the text of speeches delivered in English and of the translation of speeches delivered in other languages. The final text will be printed in the Official Records of the Security Council. Corrections should be submitted to the original languages only. They should be incorporated in a copy of the record and sent under the signature of a member of the delegation concerned to the Chief of the Verbatim Reporting Service, room -

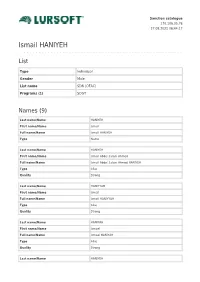

Ismail HANIYEH

Sanction catalogue 170.106.35.76 27.09.2021 06:44:17 Ismail HANIYEH List Type Individual Gender Male List name SDN (OFAC) Programs (1) SDGT Names (9) Last name/Name HANIYEH First name/Name Ismail Full name/Name Ismail HANIYEH Type Name Last name/Name HANIYEH First name/Name Ismail Abdel Salam Ahmed Full name/Name Ismail Abdel Salam Ahmed HANIYEH Type Alias Quality Strong Last name/Name HANIYYAH First name/Name Ismail Full name/Name Ismail HANIYYAH Type Alias Quality Strong Last name/Name HANIYAH First name/Name Ismael Full name/Name Ismael HANIYAH Type Alias Quality Strong Last name/Name HANIYEH First name/Name Ismayil Full name/Name Ismayil HANIYEH Type Alias Quality Strong Last name/Name HANIEH First name/Name Ismail Full name/Name Ismail HANIEH Type Alias Quality Strong Last name/Name HANIYA First name/Name Ismail Full name/Name Ismail HANIYA Type Alias Quality Strong Last name/Name HANIYAH First name/Name Ismail Full name/Name Ismail HANIYAH Type Alias Quality Strong Last name/Name HANIYA First name/Name Ismael Full name/Name Ismael HANIYA Type Alias Quality Strong Birth data (2) Birthdate 1962 Place Shati refugee camp, Gaza Strip Country Palestinian territories Updated: 27.09.2021. 05:15 The Sanction catalog includes Latvian, United Nations, European Union, United Kingdom and Office of Foreign Assets Control subjects included in sanction list. © Lursoft IT 1997-2021 Lursoft is the re-user of information from the Enterprise Register of Latvia. The user is obliged to observe the Copyright law, Personal Data Processing Law requirements and Terms of Use of the Lursoft system. -

Con Qué Derechos Estamos Seguras Palestina Tiene Nombre De Mujer

8 Mundubat es una ONGD 7 comprometida con el El presente volumen trata Nº 8 Nº7 cambio social. Entiende la de la realidad del pueblo Cooperación y la Educación palestino desde el punto Palestina tiene nombre de mujer para el Desarrollo como de vista de las mujeres. herramientas válidas par Una realidad marcada por Isaías Barreñada. Politólogo. Experto en mundo árabe. el impulso de procesos el conflicto que se vive por orientados hacia ese Juani Rishmawi. Coordinadora de Proyectos en español H.W.C. necesario cambio, tanto en más de 40 años y que tiene el escenario global como en su comienzo con la ocupación Lidon Soriano. CC. de la Educación Física y el Deporte. Universidad Camilo José Cela. Madrid. Miembro de Komite Internazionalistak el local. Así entendida, y colonización por parte de nuestra solidaridad está Israel de los territorios Teresa Aranguren. Periodista y escritora interesada en reflexionar palestinos. Este libro está Leila Al-Safadi. Jefa de redacción del diario Baniyas en el Golán. sobre todos los aspectos que dividido en dos partes: una configuran el mundo en que Khawla Al Azraq. Directora de Psychosocial Counselling Center for Women. primera de reflexiones vivimos: la política y la sociopolíticas, y una segunda Khitam Saafin. Ramala. Union of Palestinian Women Committees (UPWC). economía, la guerra y la paz, lo público y lo privado, compuesta de testimonios. Lana Khalid. Comunidad de Jayyous, región de Qalquilya. la diversidad de culturas, Estos últimos nos presentan María Rishamawi. Estudiante de Derecho. Universidad de Alcalá (Madrid) las relaciones de género... cómo viven, cómo luchan El presente libro es el octavo y cómo se organizan Smad W.T. -

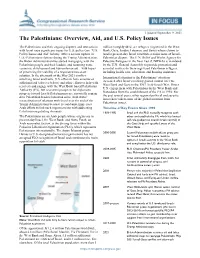

The Palestinians: Overview, 2021 Aid, and U.S. Policy Issues

Updated September 9, 2021 The Palestinians: Overview, Aid, and U.S. Policy Issues The Palestinians and their ongoing disputes and interactions million (roughly 44%) are refugees (registered in the West with Israel raise significant issues for U.S. policy (see “U.S. Bank, Gaza, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria) whose claims to Policy Issues and Aid” below). After a serious rupture in land in present-day Israel constitute a major issue of Israeli- U.S.-Palestinian relations during the Trump Administration, Palestinian dispute. The U.N. Relief and Works Agency for the Biden Administration has started reengaging with the Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) is mandated Palestinian people and their leaders, and resuming some by the U.N. General Assembly to provide protection and economic development and humanitarian aid—with hopes essential services to these registered Palestinian refugees, of preserving the viability of a negotiated two-state including health care, education, and housing assistance. solution. In the aftermath of the May 2021 conflict International attention to the Palestinians’ situation involving Israel and Gaza, U.S. officials have announced additional aid (also see below) and other efforts to help with increased after Israel’s military gained control over the West Bank and Gaza in the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. Direct recovery and engage with the West Bank-based Palestinian U.S. engagement with Palestinians in the West Bank and Authority (PA), but near-term prospects for diplomatic progress toward Israeli-Palestinian peace reportedly remain Gaza dates from the establishment of the PA in 1994. For the past several years, other regional political and security dim. -

The Palestinians: Background and U.S

The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations Jim Zanotti Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs August 17, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL34074 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations Summary This report covers current issues in U.S.-Palestinian relations. It also contains an overview of Palestinian society and politics and descriptions of key Palestinian individuals and groups— chiefly the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), the Palestinian Authority (PA), Fatah, Hamas, and the Palestinian refugee population. The “Palestinian question” is important not only to Palestinians, Israelis, and their Arab state neighbors, but to many countries and non-state actors in the region and around the world— including the United States—for a variety of religious, cultural, and political reasons. U.S. policy toward the Palestinians is marked by efforts to establish a Palestinian state through a negotiated two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; to counter Palestinian terrorist groups; and to establish norms of democracy, accountability, and good governance within the Palestinian Authority (PA). Congress has appropriated assistance to support Palestinian governance and development amid concern for preventing the funds from benefitting Palestinian rejectionists who advocate violence against Israelis. Among the issues in U.S. policy toward the Palestinians is how to deal with the political leadership of Palestinian society, which is divided between the Fatah-led PA in parts of the West Bank and Hamas (a U.S.-designated Foreign Terrorist Organization) in the Gaza Strip. Following Hamas’s takeover of Gaza in June 2007, the United States and the other members of the international Quartet (the European Union, the United Nations, and Russia) have sought to bolster the West Bank-based PA, led by President Mahmoud Abbas and Prime Minister Salam Fayyad. -

Palestine Before the Elections

Poll No. 97 | April 2021 Poll No. 97 April 2021 Palestine before the elections 1 Poll No. 97 | April 2021 Barghouthi ahead of Abu Mazen in presidential race while Fatah ahead of Hamas in PLC race Ramallah – Results of the most recent public opinion poll conducted by the Jerusalem Media and Communication Center (JMCC) in cooperation with Friedrich Ebert Stiftung showed imprisoned Marwan Barghouthi holds an advantage over President Abu Mazen if presidential elections are held as long as runners in the elections are limited to these two candidates, alongside Ismail Haniyeh. The results of the poll, which was held between April 3 and 13, showed that 33.5% of respondents would vote for Marwan Barghouthi while 24.5% would vote for Mahmoud Abbas (Abu Mazen), 10.5% would vote for Ismail Haniyeh and 31.5% said they still had no answer. Meanwhile, 60.2% said they supported the idea of Marwan Barghouthi running for president, while 19.3% said they did not support the idea. Importance of holding elections The majority of respondents, 79.2%, said it was important to hold legislative elections in Palestine as opposed to 14.3% who said it was not important. Nonetheless, the biggest majority, 44.4% said they believed the declared elections would be postponed, as opposed to 38.6% who said they expected them to be held on time. Regarding the integrity of the upcoming elections, 28.4% responded they believed they would be fair while 35.2% said they would be somewhat fair and 27.1% said they did not think they would be fair at all.