Promotion of Sanskrit Studies in Sikkim - S.K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Buddhism in Sikkim: a Study in Cultural Syncretism Richa Raj*, Alice Rai, Maxine P

DU Journal of Undergraduate Research and Innovation Volume 1 Issue 2, Page 291-302 Buddhism in Sikkim: A Study in Cultural Syncretism Richa Raj*, Alice Rai, Maxine P. Mathew, Naina Johnson, Neethu Mathew, Osheen Magu, Shivangi Singh, Srishti Gupta, Supriya Sinha, Tanya Ranjan, Urvashi Bhardwaj [email protected] Jesus and Mary College, University of Delhi, Chanakyapuri, New Delhi. 110021 ABSTRACT This study aims at „de-mystifying‟ the diverse Buddhist culture of Sikkim through an analysis of its origins, belief systems, symbols, architecture, as well as the evolving culture of the monasteries using audio and visual documentation and interviews as tools. At the same time it attempts to document the cultural assimilation of other traditions (such as Hinduism) into this religious tradition. It was observed that the religious practices of Buddhism in Sikkim were influenced by the dominant Hindu religion and pre-Buddhist religions such as Bonism. The religious assimilation of different cultures in Buddhism is mainly seen in the ritualistic practices while the architectural style was influenced by the Tibetan and localized artistic forms. This assimilation can be widely viewed among the recently-converted Buddhists, that is, the Tamang and Gurung castes. Keywords: Buddhism, culture, philosophy, rituals, Sikkim, Tibetan. INTRODUCTION About 2,500 years ago, Shakyamuni Buddha attained enlightenment after many years of intensive spiritual practice, leading to the development of one of the world‟s great religions. Standing for compassion, forbearance, love, non-violence and patience, Buddhism further percolated to the neighbouring countries forming its own identity therein. As heresy against Brahmanism, it sprang from the kshatriya clans of eastern India and advocated the middle path. -

THE Presidency COLLEGE MAGAZINE

THE PRESIDENCy COLLEGE MAGAZINE Cr STENTS PAflK FOEK.WOKD NoMiS AND NKVS 1 LEAVES OF GiiASr^s SERVILE PoPlILATroN IN VKDIC [XDIi ... ... 19 SAKATCIIAXDUA : Ajr APPKKCIATIOJJ ... ... 2,5 A SOXNET 32 IjEGTfrTATrVH SOVEP.EKINTY OF THE BoiriNION.q 33 PvAi RASAMOY MITKA BAHADFR 38 TX'l-ERNATIONAIJSJt & TMPERIAIJS:\t ... ... 4.'! AN APPEF CAIIT ... ... ... 52 Orrp.sELVEs ... ... ... h" f^stS^^WW ... ••' •-• i ^5(1 ... •- - « ^t^j«^t^^ '«i§^r^ ... ... •- "> <pj^-<<iiT>f^ ^r<i5<i ... ... ... i« <[f}S-^f?Plf ••• ••• ••• ^9 ^[%5I-»t<I«. ^f^f^ ••• •- ••• ^i > Vol. XYIU OCTOBER, 1931 No. 1 ^ s s 1 NOTICE < S s > 1 Hi'. A. p. 1 Ariii'ua.l •./ibpcviplioii in India inclml- 'i 1 iiig jiostage ... ^...2 S 0 ^S ^ 1 For Stmleiits of Prosideuey Colle-o ... ISO s ^ Single copy ... ... ... 0 10 0 <s 1 Foreiii-ii Subscription ... ... 4 Sbillingp. ^ s $ Idicre wll! oi^linavilv lie throe issues a year, in Septem- s 5 ber, l)eceml:er and Mareli. ^ •« Siudents, old Ficsidcney College men and members of J the Staff ')f ibe ('nllcgc are invited to contribute to the ^ Mairazine. Shoi't ;U;d interesting articles written on subjects J of i^'onerad irnorest iind letters dealing in a fair spirit v.dtli < colleoe and Unix'orsity matters will be welcome. The ]<^ditor 1 cannot return rojeeicil artirdes unless accompanied by stamped \ and addressed envelope. ^ All contributions for publication musi, l:e wrivuen on one $ side of the pap'or and must b-e acompa^uied by the full name ^ and address of the writer, not necessarily for publication but \ as a guarantee of good faith. -

Gandhi News Vol. 12 No.1

April-June 2017 Editor : Prof. Jahar Sen §¡õyòܲ ≠ ç•Ó˚ ˆ§l Contribution : Rs. 20/- !Ó!lÙÎ˚ ≠ 20 ê˛yܲy GANDHI NEWS ày¶˛# §ÇÓyò ~!≤ðÈüÈç%l 2017 §)!ã˛˛õe 1. Editorial : Wardha Scheme— 05 Gandhian Approach to Education 2. Champaran : Report sent by Mahatma Gandhi 09 from Bettiah to Chief Secretary Bihar and Orisea on 13 May 1917 3. Nirmal Chandra Sinha : Asian Relations and Gandhi 16 4. Tapan Kumar : Swaraj— Utopian or Realistic Goal 31 Chattopadhyay 5. Ù•ydy ày¶˛#ˆÏܲ ≤ÃÊ%˛Õ‘ã˛w ˆ§ˆÏlÓ˚ !ã˛!ë˛ 35 6. ô&Ó =Æ ≠ Ü,˛£èyD xyˆÏÙ!Ó˚ܲyˆÏlÓ˚ ˆã˛yˆÏá ày¶˛# 39 7. xÙ,ï˛°y° ã˛ˆÏRy˛õyôƒyÎ˚ ≠ flø,!ï˛Ü˛Ìy 45 8. Director-Secretary’s : Director-Secretary’s Report on 47 Report the Programme and Activities at Gandhi Smarak Sangrahalaya, Barrackpore, from 1st March, 2017 to 16th May, 2017 Editorial WARDHA SCHEME Gandhian Approach to Education he Gandhian approach to education can be best set out in terms of the Tresolutions passed at Wardha National Education Conference in October 1937. The conference passed resolutions on the following issues. 1. Free and compulsory education should be provided for seven years on a nation-wide scale. 2. The medium of instruction should be the mother-tongue. The conference endorsed the proposal of Mahatma Gandhi that the process of education throughout this period should centre round some form of manual and productive work and that ‘‘all other abilities to be developed or training to be given, should as far as possible be integrally related to the central handicraft, chosen, with due regard to the environment of the child.’’ The conference expected that this system of education would gradually be able to cover the remuneration of the teachers. -

Author Index, 1998

AUTHOR INDEX, 1998 Acharya, Alka: Leading the Region and Ananth, Mallika: Oil Conservation: Urgent Leading the World: China (C) Need (LE) Issue no: 45, Nov 07-13, p.2835 Issue no: 07, Feb 14-20, p.306 Acharya, Debashis and Bandi Kamaiah: Angadi, V B: Price Stability, BoP Currency Equivalent Monetary Equilibrium and Economic Growth (BR) Aggregates: Do They Have an Edge over Issue no: 39, Sep 26-Oct 02, p.2521 Their Simple Sum Counterparts? (SA) Issue no: 13, Mar 26-Apr 03, p.717 Anitha, K; H N Naveen and R Kiran Kumar: Role of Local Elected Leaders in Lok Adnan, Shapan: Fertility Decline under Sabha Elections (C) Absolute Poverty: Paradoxical Aspects Issue no: 09, Feb 28-Mar 06, p.443 of Demographic Change in Bangladesh (SA) Anjaiah, P: See Rao, B Janardhan Issue no: 22, May 30-Jun 05, p.1337 Issue no: 46, p.2882 Agarwal, Bina: Disinherited Peasants, Antia, N H: Public Health Institute (LE) Disadvantaged Workers: A Gender Issue no: 12, Mar 21-27, p.618 Perspective on Land and Livelihood (RA) Issue no: 13, Mar 26-Apr 03, p.A2 Anuradha, B: Arrest and Torture of Women's Organisation Activist (LE) Agnihotri, S B: See Das, D Issue no: 04, Jan 24-30, p.134 Issue no: 52, , p.3333 Anuradha, R V: Mainstreaming Indigenous Agrawal, Pradeep: Lessons from Emerging Asia Knowledge: Developing Jeevani (P) (BR) Issue no: 26, Jun 27-Jul 03, p.1615 Issue no: 01, Jan 10-16, p.26 Ari, Sitaramayya et al: Custody Deaths in Ahmed, Inam: See Dixit, Kunda Andhra Pradesh (LE) Issue no: 44, p.2772 Issue no: 39, Sep 26-Oct 02, p.2490 Alagappan, A R: See Manickavasagam, -

Bulletin of Tibetology Seeks to Serv3 the Specialist As Well As the General Reader with an Interest in This Field of Study

Bulletin of VOL. II No. 1.. 4 March 1965 NAMGYAL INSTITUTE OF TlBETOLOGY GANGTOK. SIKKIM --The Bulletin of Tibetology seeks to serV3 the specialist as well as the general reader with an interest in this field of study. The motif portraying the Stupa on the mountains suggests the dimensions of th9 field- EDITORS GYALMO HOPE NAMGYAL T. SHERAB GYAlTSHEN NIRMAl C. SINHA Bullet;n Vol. II No. 1. '1' ... " 4 MARCH 1965 NAMGYAL INSTITUTE OF TIBETOlOGY GANGTOK. SIKKIM "".... --' 'fJ~a::f·~·"'9C::·filll·"l~z:.· a;~' ~q'~' G~G ...:> , st published 4 March, 1965 Reprinted 1 Saptember, 1991 Printed at Impression Gangtok Published by The Director Namgyal Institute of Tibetology Gangtok CONTENTS Page HOW OLD WAS SRONG BRTSAN SGAMPO 6 H. E. RICHARDSON PRINCIPLES .oF BUDDHIST TANTRISM 9 LAMA ANAGARIKA GOVINDA THE TIBETAN TRADITION OF GEOGR PHY 17 TURR~LL V. WYLIE . UTTARAKURU' 2'7 BUDDHA PRAKASH NOTES &. TOPICS 36 NIRMAL C. SINHA CONTRIBUTORS IN THIS ISSUE: HUGH eDWARD RICHARDSON Held diplomatic assignments in lhasa (1936.40 & 1946-50) and Chungking (1942-44); reputed for linguistic abilities. knows several Asian languages. speaks lhasa cockney and reads . classical Tibetan with native intonation, conversed with the poet Tagore in Bengali; was (1961-62) Visiting Professor in Tibetan languaQe and history at University of Washington. Seattle, USA; reCipient of the Gold Medal of the Royal Central Asian Society, UK; lelding authority on history of Tibet, ancient as well as modern, LAMA ANAGARIKA GOVINDA An Indian national of European (German) descent and Buddhist (Mahayana) faith; began asa student of humanities in Western discipline ) Friebury. -

Bimal Prasad Manohar Publisher…

This view Authorrequires setWantsLayer:YES when Title blendingMode == NSVisualEffectBlendingModeWithinWindow Publisher User Lookup 1 Bimal Prasad Manohar Publisher… Himansu Bhusan Sarkar Cultural Relations Between India And Southeast Asian Countries C.0004 Shankarrao Shantaram More Practice And Procedure Of Indian Parliament Thacker G.0078 10 Years Asean. ASEAN G.0558 100 Best Pre-Independence Speeches, 1870-1947 HarperCollins H.0044 100 Glorious Years Reception Committ… G.0560 100 Himalayan Flowers Grantha Corporation C.0224 Neeta Datta 1000 Great Indian Recipes Roli Books Pvt Ltd C.0018 101 Panchatantra Stories B.0012 1993 Directory of Indian Schools Database Publishing D.0016 1993 United Nations Handbook Ministry of Foreign… G.0111 Indira Chandrasekhar 20 Stories From South Asia Katha F.0018 South Asia Defence And Strategic Year Book. Panchsheel G.0583 India Who's Who. INFA Publications D.0018 Kishan S. Rana The 21st Century Ambassador: Plenipotentiary To Chief Executive Oxford University P… G.0238 Kishan S. Rana 21st Century Diplomacy Continuum Intl Pu… G.0182 22 Short Short Stories CBT Publications B.0057 Nicolas Bourriaud 25 Contemporary Indian Artists Ravi Kumar Publisher A.0022 Oliver Rathkolb 250 Jahre Studien Verlag G.0018 Ankur Mitra 30 Teenage Stories Children's Book Trust B.0068 Om Books 365 Animal Tales Om Books Internati… B.0026 Books Om 365 Folk Tales Om Books Internati… B.0011 Sibadas Chaudhuri 4 Index internationalis indicus 1979 Sompa Chaudhuri D.0024 5 In 1: Ancient Tales Of Wit And Wisdom B.0010 Nilima Sinha 5 Mystery Stories F.0189 50 Years Of India's Independence Manas Publications G.0390 Rupinder Khular 501 Images Of The Taj Mahal And Glimpses Of Mughal Agra Prakash Book Depot H.0011 Avtar Singh Bhasin ASEAN India ASEAN Multilateral… G.0626 Atulananda Chakrabarti ASHOKA for the young The Good Books B.0093 Amaan Ali Khan Abba - Lustre Press A.0041 Vikas Swarup Accidental Apprentice Pa Simon & Schuster F.0001 F.C. -

KRC Lib. Booklist-5.16.018

1 | PageList of books donated to ANHS The Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies S.l. No. Name of the books Author Year of Publication Published By Copy Short poems1 Laxmi D. rajbhandari First impression L axmi D. Rajbhandari 1999 Studies in nepali history and society2 Pratyoush onta Volume 1 NO. 2 Mandala book point Two copy Mary des chene December 1996 Kathmandu Nepal Lazima onta –bhatta Mark liechty Studies in Nepal history and society3 L axi D. rajbhandari 1999 Mandala books point Crime and punishment in Nepal 4 Lulasi ram vaidya tri First edition 1985 Bini vaidya and purna devi Ratna Mananadhar M anandhar Faith Healers a force for chance5 Ramesh m. Shrestha with October 24, 1980 Published with unicef mark lediard napal assistance Himalayan pil grimage6 David Snellgrove 1989 Whisper poems 7 Db gurung 1992 Prakash gurung Studies in nepli history and society8 Pratyoush onta 1998 Mandala books point Marry des chene Lazima Kathmandu nepal onta –bhatta mark liechty Decision making in vi9 llage Nepal Casper J. MILLER ,s 1990 Pilgrims publishing Rangelands and pastoral development in 1 DANIEf J. MILLER Sienna Nov-96 International centre for 0 the HKH PROCEEDING OF A REGIONAL craing integrated mountain EXPERTS MEETING development The judicial customes of Nepal1 Kalsher bahadur k.c. Second edition, 1971, Ratana pustak bhandar 1 ENGLISH1 - Tibetan dictionary of modern MelvynC. Goldstein 1984 Library of Tibetan works and ,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,, 2 tibetan With ngawangthondup archives Narkyid Tibatan reflections 1 Peter gold First published 1984 Wisdom publication 3 Methods in applied ethnobotany 1 Ajay rastogi 1999 Internation centre for 4 integrated mountain development Lessons from the field Kathmandu Nepal kailash1 Charles ramble. -

Sources Utilisées Pour Élaborer Le Dictionnaire

SOURCES UTILISÉES POUR ÉLABORER LE DICTIONNAIRE L’ossature de ce dictionnaire est faite sur la base du vocabulaire que j’ai acquis au fil de mes traductions du tibétain et des glossaires que je me suis constitués petit à petit. J’ai ensuite enrichi le contenu en effectuant de patientes recherches dans les travaux des tibétologues, les livres publiés en anglais comme en français et en explorant les différents glossaires et dictionnaires déjà existants. Vous trouverez ci-dessous une liste non exhaustive des sources auxquelles je me suis référé pour la collecte des mots et le choix des traductions, sachant qu’elles ne représentent qu’une partie, néanmoins significative, de mon travail de recherche. Je ne peux citer ici les très nombreuses sources tibétaines qui m’ont permis d’acquérir le vocabulaire nécessaire 1 pour ce dictionnaire car il s’agit en réalité de tous les textes et ouvrages sur lesquels ont porté mes travaux de traduction depuis une vingtaine d’années… JF Buliard, 2017 DICTIONNAIRES DE RÉFÉRENCE SUR INTERNET : − Tibetan and Himalayan Library (THL) : outil de traduction tibétain-anglais (Translation Tool) (http://www.thlib.org/reference/dictionaries/tibetan-dictionary/translate.php) − Rangjung Yeshe Dictionary (http://nitartha.pythonanywhere.com/search) SOUS FORME NUMÉRISÉE : − Illuminator Tibetan-English Dictionary , Tony Duff − Tibetan-English Dictionary , Sarat Chandra Das, Bengal Secretariat Book Depôt, 1902 − Tibetan-Sanskrit-English Dictionary , Jeffrey Hopkins, Digital version: Digital Archives Section, Library and Information center of Dharma Drum Buddhist College, 2011 − Zhangzhung dictionary , Dan Martin, Revue d’Études Tibétaines, avril 2010 − Bod rgya tshig mdzod chen mo , Nationalities Publishing House, Beijing, 1993 − Dung dkar tshig mdzod chen mo , China Tibetology Publishing House, Beijing, 2002. -

LIST of BOOKS in LIBRARY Title of S.No

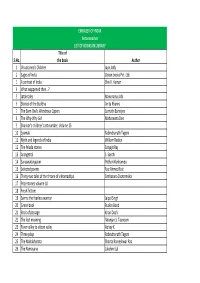

EMBASSY OF INDIA Antananarivo LIST OF BOOKS IN LIBRARY Title of S.No. the book Author 1 Visvakarma's Children Jaya Jaitly 2 Sages of India Ocean books Pvt. Ltd. 3 A portrait of India Shiv K. Kumar 4 What wappened then…? 5 Jatak tales Manorama Jafa 6 Stories of the Buddha Anita Khanna 7 The Barn Owl's Wondrous Capers Sarnath Banerjee 8 The Why-Why Girl Mahasweta Devi 9 Shankar's children's art number, Volume 35 10 Syamali Rabindranath Tagore 11 Myth and legends of India William Radice 12 The feluda stories Satyajit Ray 13 Arangetral S. Santhi 14 Saraswativijayam Potheri Kunhambu 15 Selected poems Faiz Ahmed Faiz 16 Thirty-two tales of the throne of vikramaditya Simhasana Dvatrimsika 17 Prize stories volume 10 18 Fresh fictions 19 Samru the fearless warrior Jaipal Singh 20 Green book Ruskin Bond 21 Birds of passage Kiran Doshi 22 The lost meaning Niranjan S. Tasneem 23 River valley to silicon valley Abhay K. 24 Three plays Rabindranath Tagore 25 The Mahabharata Shanta Rameshwar Rao 26 The Ramayana Lakshmi Lal 27 The Mahabharata Bany Roy Chowdhary 28 Life story of Guru Nanak Prof. Kartar Singh 29 The story of Guru Nanak Mala Singh 30 Sacred literature of the Hindus Rev. R. Wrightson 31 Selected short stories Rabindranath Tagore 32 The boatman boy and forty poems Sochi Raut Roy 33 An illustrated history of Indian literature in English Arvind Krishna Mehrotra 34 Stories and parables Sant Keshavadas 35 The lunar visitations Sudeep Sen 36 Diet and diet reform M.K. Gandhi 37 Fragrant flowers 38 Favourite fiction II The little magazine 39 The fifth element Manju Seth 40 Imagine the others G.J.V. -

Proposed Date of Transfer to IEPF (DD-MON-YYYY)

First Name Father/Husband First Name Address Country State PINCode Folio Number of Securities Amount Due(in Rs.) Proposed Date of transfer to IEPF (DD-MON-YYYY) VISHWANATH PRASAD NA RAM NIWAS 63 A RAVINDRA PURI VARANASIINDIA VARANASIUttar Pradesh 221005 0000IN30001110764992 52.50 29-DEC-2016 VIJENDRA MISHRA B L MISHRA LIG-10 HOUSING BOARD NARINGPUR (M P) INDIA Madhya Pradesh 482001 0000IN30039414035999 52.50 29-DEC-2016 VIJENDER SINGH SWARAN SINGH H.NO-16, J-BLOCK, DHARAMPURA, NAJAFGARHINDIA NEW DELHIDelhi 110043 00001202600000023890 52.50 29-DEC-2016 VIJAY PRASAD CHANDRA SEKHAR PRASADA 1 UMA ENCLAVE KALYANPUR ROAD NO 4 SINGHINDIA MOREJharkhand HATIA RANCHI 834003 0000IN30267932282088 420.00 29-DEC-2016 VENKATESH DAS MULLICK NA 96 BHUPEN BOSE AVENUE CALCUTTA INDIA West Bengal 700004 0000000000CWV0018356 105.00 29-DEC-2016 VEERA VENKATA SUBBARAO CHCHAKKA RADHA KRISHNA MURTHYDOOR NO 1-65 MALLAVOLU VILLAGE AND POSTINDIA GUDURUAndhra MANDAL Pradesh KRISHNA521162 DIST 0000IN30232410834425 52.50 29-DEC-2016 VEENA DILIP PARIKH DILIP PRAVINCHANDRA PARIKH20, VAIBHAV BUNGLOWS PART-1, NR. SUN N STEPINDIA CLUB,Gujarat GHATLODIA, AHMEDABAD.380061 0000IN30034310901832 52.50 29-DEC-2016 VEENA APPANNA K APPANA K M HILL VIEW ESTATE CHERALA, PB.NO.25 SRIMANGALAINDIA Karnataka CHETTALLI PO 571248 0000IN30023911464987 52.50 29-DEC-2016 VEDAMBAL KN KANNAPPA CHETTIAR K AR K2 AR 45 KNORTH MASI STREET MADURAI INDIA Tamil Nadu 625001 0000IN30017510069000 147.00 29-DEC-2016 VARSHABEN G MANIYA GHANSHYAMBHAI PLOT NO 57, BAZMENT SHREEJI NAGAR VIBHAGINDIA - 2, VEDROAD,Gujarat