Waterlat Gobacit Network Working Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tampere University Speech by President Mari Walls at the Opening of the Academic Year on 10 September 2019

1 Tampere University Speech by President Mari Walls at the opening of the academic year on 10 September 2019 Honoured guests, dear colleagues, alumni and friends of Tampere University. It is my great pleasure to welcome you all to celebrate the opening of our University’s first academic year! The idea to establish a unique new higher education community in Tampere can be traced back to more than five years ago when it was first formulated during discussions involving Kai Öistämö, Tero Ojanperä and Matti Höyssä, who presided over the Boards of the three Tampere- based higher education institutions, and then-Presidents of the institutions Kaija Holli, Markku Kivikoski and Markku Lahtinen. In spring 2014, the three institutions commissioned Stig Gustavson to identify areas where they could establish a leading international reputation and determine the necessary steps to achieve this vision. The 21 founding members signed the Charter of Tampere University Foundation on 20 April 2017. As set out in the Charter, the old, distinguished University of Tampere and Tampere University of Technology were to be merged to create a new university with the legal status of a foundation. The new university was also to become the majority shareholder of Tampere University of Applied Sciences. The agreement whereby the City of Tampere assigned its ownership of Tampere University of Applied Sciences Ltd to Tampere University Foundation was signed on 15 February 2018. Our new Tampere University started its operations at the beginning of this year. Today marks the 253rd day since the launch of the youngest university in Finland and in Europe. -

Leading a Fundamentally Detuned Choir: University of Tampere, Finland – a Civic University?

[Draft chapter – will be published in Goddard, J., Hazelkorn, E., Kempton, L. & Vallance, P. The Civic University: the Policy and Leadership Challenges. Edwar Elgar.] Markku Sotarauta Leading a Fundamentally Detuned Choir: University of Tampere, Finland – A Civic University? 1 Introduction A university is an academic ensemble of scholars who are specialised and deeply dedicated to a particular branch of study. Often scholars are passionate about what they do, and are willing to listen only to those people they respect, that is their colleagues and peers, but not necessarily heads of their departments, faculties or research centres. Despite many efforts, university leaders more often than not find it difficult to make academic ensembles sing the same song. If a group of singers perform together, it is indeed a choir. A community of scholars is not necessarily so. Singers agree on what to sing and how, they know their sheets, and a choir leader conducts them. A community of scholars, however, is engaged in a continuous search for knowledge through the process of thesis and antithesis, debates, as well as conflicts and fierce rivalry – without an overarching conductor. Universities indeed are different sorts of ensembles, as scholars may not agree about what is and is not important for a university as a whole. By definition a university is not a well-tuned chorus but a proudly and fundamentally detuned one. Leadership in, and of, this kind of organic entity is a challenge in itself, not to mention navigating the whole spectrum of existing and potential stakeholders. Cohen and March (1974) see universities as ‘organized anarchies’, as the faculty members’ personal ambitions and goals as well as fluid participation in decision- making suggest that universities are managed in decidedly non-hierarchical terms, but still within the structure of a formally organised hierarchy. -

Näsijärvi Pyhäjärvi

Kuru Mäntylä 85 90 Velaatta Poikelus 85 90 Orivesi 47, 49, 95 Terälahti 90 Mutala Maisansalo 90A 85 90C Teisko kko 90B Oriveden Lakiala Vastamäki asema Asuntila 92 95A 81 90 Hietasmäki 84 Viitapohja Kämmenniemi 92 90, 92 28 Moisio Iso-Kartano 80, 81, 84, 85 Siivikkala 90, 92 Peuranta Metsäkylä 80 92 83 Haavisto Eerola Honkasalo 90, 92 28 Julkujärvi 95 83 Kirkonseutu Kintulammi Elovainio 80, 81, 84, 85 92 83 Aitoniemi Eräjärvi Pappilanniemi 49 80-85 91 83 Sorila Taraste Pohtola 28A, 90-92 28B Ylöjärvi 28 Aitolahti Ruutana 80-85 91 28B Nurmi 80 Ryydynpohja Laureenin- Lentävänniemi 8Y, 28, 90 9, 19, 38 kallio 28B 85 Pohjola 80Y, 81 Olkahinen Järvenpää Ryydynpohja Niemi Reuharinniemi Näsijärvi 8Y, 28, 90 49 14 14 14 14 80 Lintulampi Teivo 28 Vuorentausta Kumpula 85 80Y, 81 14 8Y, 28, 90 9, 19, 38 80, 81 Niemenranta 20 8 Haukiluoma 21, 71, 80 8 Lamminpää 21,71 85 Rauhaniemi Atala 21 21,71 Lielahti 95 9, 14, 21, 19, 28, 38, 71, 80 2 28, 90 8 81 Potilashotelli 29 Tohloppi 5, 38 Ikuri 71 20 Lappi Ruotula Niihama 8, 29 Epilänharju Hiedanranta 2 Tays Arvo Särkänniemi Ranta-Tampella 1, 8, 28, 38, 42, 1, 8, 28, 38, 42, 28, 29, 90 Risso 21 8 Tohloppi 9, 14, 21, 19, 28, 38, 80 5, 38 90, 95 Myllypuro 100 11, 30, 31 Petsamo 90, 95 29 81 Santalahti 15A Tesoma Ristimäki 9, 14, 19, 21, 26 8, 17, 20,21, 26, 71 9, 14, 19, 21, 38, 71, 72, 80, 85 71, 72, 80, 85, 100 2 Osmonmäki 8 15A, 71 8, 17 Tohlopinranta Tays 8Y 38 38 Saukkola 80 Linnavuori 71 71 26 5, 38 1, 8, 28, 29, 80, 90, 95 29 42 79 17 26 15A 8, 17, 20, 15, Amuri Finlayson Jussinkylä Takahuhti Linnainmaa -

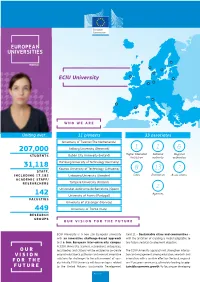

ECIU University

ECIU University WHO WE ARE Uniting over… 11 pioneers 33 associates University of Twente (The Netherlands) 1 1 6 207,000 Aalborg University (Denmark) Dublin City University (Ireland) Higher Education National Regional STUDENTS Institution authority authorities Hamburg University of Technology (Germany) 31,118 Kaunas University of Technology (Lithuania) 8 13 2 STAFF, INCLUDING 17,182 Linköping University (Sweden) Cities Enterprises Associations ACADEMIC STAFF/ Tampere University (Finland) RESEARCHERS 2 Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (Spain) Agencies 142 University of Aveiro (Portugal) FACULTIES University of Stavanger (Norway) 449 University of Trento (Italy) RESEARCH GROUPS OUR VISION FOR THE FUTURE ECIU University is a new pan-European university Goal 11 – Sustainable cities and communities – with an innovative challenge-based approach with the ambition of creating a model adaptable to and a true European inter-university campus. any future societal development objective. At ECIU University, learners, researchers, enterprises, OUR local bodies and citizens will be enabled to co-create The ECIU University approach will strengthen interac- VISION original educational pathways and relevant innovative tion and engagement among education, research and solutions for challenges to the advancement of soci- innovation, with a positive effect on the local, regional FOR THE ety. Initially, ECIU University will focus on topics related and European community, ultimately leading to sus- FUTURE to the United Nations Sustainable Development tainable -

Pyynikki Circuit

Pyynikki Circuit Pyynikki is a district and a nature reserve in Tampere, Finland. It is located in the Pyynikinharju ridge, between the city center and the western district of Pispala. Pyynikinharju is the highest esker in the world, rising 85 meters above the level of lake Pyhäjärvi.Tampere Circuit was a motorsport race track which ran on public streets of Pyynikki. Pyynikki is a district and a nature reserve in Tampere, Finland. It is located in the Pyynikinharju ridge, between the city center and the western district of Pispala. Tampere Circuit was a motorsport race track located in Tampere, Finland. The route was used for an annual motorcycle race called Pyynikinajo in 1932-1939 and 1946-1971. In 1962 and 1963, the circuit hosted the Finnish motorcycle Grand Prix, a round of the Grand Prix motorcycle racing world championship. The track ran on public streets of the Pyynikki district. The event was banned after 1971 due to general safety concerns. street circuit in Tampere, Finland. Pyynikki Circuit (Q2120091). From Wikidata. Jump to navigation Jump to search. street circuit in Tampere, Finland. Tampere Circuit. edit. Language. Pyynikki. New York has Central Park, but how many cities can boast about having a central forest? One of the Tampere city centre neighbourhoods, Pyynikki, is home to a gorgeous pine tree forest on top of a ridge. In the forest there is an illuminated jogging trail that becomes a skiing trail in the winter, and the view from the high cliffs will take your breath away. Het Pyynikki Circuit is een voormalig stratencircuit in de Finse stad Tampere. -

Download Details

Finlaysoninkuja, Finlaysoninkuja 9, Tampere, Finland View this office online at: https://www.newofficeeurope.com/details/serviced-offices-finlaysoninkuja-9-t ampere These pleasant and comortable offices have recently been renovated to provide a fully serviced office environment in a period building. Facilities provided include meeting rooms and 24 hour security. The office windows give spectacular views of the courtyard or Tammerkoski River, and there is a kitchen on site for you to use. Transport links Nearest railway station: Tampere Nearest road: Nearest airport: Key features 24 hour access Access to multiple centres nation-wide Access to multiple centres world-wide AV equipment Close to railway station Conference rooms High-speed internet (dedicated) IT support available Meeting rooms Period building Reception staff Security system Shower cubicles Town centre location Location Located in the old industrial area of Tampere, the centre is easily accessible by road, with bus stops nearby. Tampere- Pirkkala Airport is only twenty minutes away, and other nearby amenities include museums, restaurants and hotels. Points of interest within 1000 metres Plevna (parking) - 123m from business centre Tyonpuisto (park) - 201m from business centre Aleksandra Siltanen's Park (park) - 205m from business centre Jack the Rooster (restaurant) - 249m from business centre Finlaysonin kirkko (place of worship) - 266m from business centre Keskikosken voimalaitos (power generator) - 270m from business centre Sokos Hotel Tammer (hotel) - 297m from business centre Tammer -

Useful Info Explore the History Pop By

Naistenlahden voimalaitos 7 EXPLORE THE HISTORY Satamatoimisto 6 6 37 5 Visit the Finlayson and Tampella areas to witness the new life Myllysaari Kekkosenkatu 2 4 Rauhaniementie of the industrial heritage sites. Admire the national landscape, den Parantolankatu kanlah katu 11 Näsijärvi Sou2 15 historical red brick buildings and roaring rapids. Operational in- Pursikatu 19 Kekkosentie ARMONKALLIOHelenankatu dustrial areas and hydroelectric plants coexist in harmony with 95,2 5 19 esplanadi 5 13 Särkänniemi Tampellan 21 4 Soukkapuisto 11 restaurants, movie theatre, cafés, and stores that nowadays 2 16 2 9 7 1 Kaivokatu Tunturikatu 1 8 Helenankuja 5 inhabit some of the former industrial buildings. Walk down by 2 Tammelan puistokatu Tammelan 25 8 6 3 1 7 the rapids towards Kehräsaari where you fi nd the idyllic old 5 6 2 7 3 4 Pohjoinen 4 2 Siltakatu Naistenlahdenkatu Haarakatu 2 Kaarikatu 11 Pohjankulma 6 Moisionkatu factory milieu, which is worth visiting. It is a home to design Välimaankatu6 katu 5 Välimaanpolku Huvipuisto 8 8 2 5 2 5 13 5 3 tu and artisan boutiques, restaurants and an independent Yrjön äka 5 31 TOURIST MAP 8 6 7 25 Kauppi Pajasaari Törngrenin Ihanakatu13 15 17 Pohjolankatu movie theatre Niagara. An es- Sara Hildènin taidemuseo Lepp ratapihankatu 9-11 aukio Rohdin kuja 2-4 VISITTAMPERE.FI Näsinneula 32 30 33 sential part of the city’s history, Kaivokatu 22 10 15 7 Pohjolankatu 18-20 10 13 11 Verstaankatu 11 2 9 10 12 esplanadi 28 5 29 58 Kihlmaninraitti 9 3 and some of the architectural Tel: +358 3 5656 6800 28 Siltakatu 4 sandranenonen 17 6 Akvaario-Planetaario TAMPELLA 7 10 1 pearls of Tampere, are Finlayson Osmonkatu Osmonraitti 9 14 visittampere@visittampere.fi Keernakatu 7 2 2 3 24 Palace, Näsilinna and Tampere Osmonpuisto 17 Runoilijan Tampellan Pajakatu 9 1 Pellavan- 14 Annikinkatu Cathedral. -

22–25 August 2012

First Announcement 4th International Dry Toilet Conference 22–25 August 2012 University of Tampere, Finland are warmly welcome to the 4th International Dry Toilet Conference to You be held in Tampere, Finland on 22nd to 25th of August 2012. The three previous conferences were succesful and inspired us to keep on organizing this international event in the field of sustainable sanitation. We wish it will bring forth fruitful ideas and policies around the world. Global Dry Toilet Association of Finland | www.drytoilet.org/dt2012 ProPosAls For PAPers the main theme of the conference will be “Drivers for ecological dry toilets in urban and rural areas” oral and poster presentations will be chosen by the scientific committeeon the basis of abstracts received. the deadline for abstract submission is 15 January 2012. the length of the abstract is 300 - 500 words fitted on one A4 format page. the official language of the conference is english. © sari Huuhtanen © erkki Karén conFerence venue the conference will be organised in tampere, the third largest city in Finland with a population of 213 000. tampere is a city of commerce, technology, arts and sciences as well as an important educational centre laying between two beautiful lakes and partly on top of an imposing ridge. For further information, please visit the city’s website for tourists (in english and russian) » here! tourist Brochures in PDF-format are published also in swedish, german, spanish, italian, French and Japanese. Hard copies of the brochures can be ordered free of charge at the Visit Tampere Brochure order site. the venue of the conference is the university of tampere. -

Tampereen Sähkölaitos Oy's

ECO2 Kirjaorig english:ECO 2 Kirjaorig 24.10.2013 10:32 Sivu1 First3 years TAMPERE ECO2 Kirjaorigenglish:ECO224.10.201310:32Sivu2 Emil Bobyrev ECO2 Kirjaorig english:ECO 2 Kirjaorig 24.10.2013 10:32 Sivu3 Tammerkoski rapids – The heart of the city. ECO2 Kirjaorig english:ECO 2 Kirjaorig 24.10.2013 10:32 Sivu4 CITY OF TAMPERE Founded in 1779. The third largest city in Finland and one of the three most rapidly growing regions in Finland. Population 2013: 220,000. Area: City 689.6 km², Land 525.0 km², Water 164.6 km². ECO2 Kirjaorig english:ECO 2 Kirjaorig 24.10.2013 10:32 Sivu5 First years ECO2 Kirjaorig english:ECO 2 Kirjaorig 24.10.2013 10:32 Sivu6 First years © City of Tampere/ECO2-project © Writers © Photographers Editorial staff Pauli Välimäki Elli Kotakorpi, Krista Willman, Kirsi Viertola Mikko Närhi Graphic design and layout Nalle Ritvola, Osakeyhtiö Nallellaan, Tampere Photos If not stated, the City of Tampere Mikko Närhi Nalle Ritvola Translation Translatinki Oy Printing Hämeen Kirjapaino Oy, 2013 ISBN 978-951-609-710-0 6 ECO2 Kirjaorig english:ECO 2 Kirjaorig 24.10.2013 10:32 Sivu7 Contents Foreword by the Mayor of Tampere: Towards a Smart Eco-city 9 Introduction. What is the ECO2 project? 10 Eco-efficient city planning and construction • Energy surveys made part of the planning • Eco-efficient city planning process (Chart) • Tampere’s roadmap for energy-smart construction 15 Examples of eco-efficient construction • An eco-city in Vuores • Lantti, Finland’s first zero-energy house • PuuVuores project 21 progresses • Härmälänranta -

Mess in the City at the Moment, It's the New Tram Network Being Built

mess in the city at the moment, it’s the new tram network being built Moro! *) -something that we worked for years to achieve and are really proud of. Welcome to Tampere! So welcome again to our great lile city! We are prey sure that it’s the best Tampere is the third largest city and the second largest urban area in Finland, city in Finland, if not in the whole Europe -but we might be just a lile bit with a populaon of closer to half a million people in the area and just over biased about that… We hope you enjoy your stay! 235 000 in the city itself. The Tampere Greens Tampere was founded in 1779 around the rapids that run from lake Näsijärvi to lake Pyhäjärvi -these two lakes and the rapids very much defined Tampere and its growth for many years, and sll are a defining characterisc of the *) Hello in the local dialect city. Many facories were built next to the energy-providing Tammerkoski rapids, and the red-brick factories, many built for the texle industry, are iconic for the city that has oen been called the Manchester of Finland -or Manse, as the locals affeconately call their home town. Even today the SIGHTS industrial history of Tampere is very visible in the city centre in the form of 1. Keskustori, the central square i s an example of the early 1900s old chimneys, red-brick buildings and a certain no-nonsense but relaxed Jugend style, a northern version of Art Nouveau. Also the locaon of atude of the local people. -

RANTATIE 43, 33250 TAMPERE Visualisointikuvassa Taiteilijan Näkemys Erinan Julkisivusta JÄRVEN RAUHA KOTONA KAUPUN- GISSA

ASUNTO OY TAMPEREEN PISPARANNAN ERINA RANTATIE 43, 33250 TAMPERE Visualisointikuvassa taiteilijan näkemys Erinan julkisivusta JÄRVEN RAUHA KOTONA KAUPUN- GISSA Vedellä on aina ollut erityislaatuinen merkitys suo- malaisille. Sen lisäksi että saamme nauttia maailman puhtaimmasta vedestä, se tarjoaa meille ympärivuo- tisen virkistäytymisen muun muassa uinnin, veneilyn 4 tai kalastamisen muodossa. Maisema on kuin postikortista. Järvimaisemaa par- vekkeeltaan ihastellessa saattaa jopa unohtaa, että asuu kaupungissa. Kaupunkiasuminen ei tarkoita, että omista ehdoistaan tulee luopua. Santalahti yhdistää unelman urbaanista asumisesta järvimaise- masta tinkimättä. Santalahdesta muodostui aikanaan keskeinen teol- lisuusalue sijaintinsa ansiosta Näsijärven rannalla, Tampereen keskustan kainalossa. Tulitikkujen, pa- perin ja pahvin valmistus kukoisti ja alueen yritykset olivat suuri paikallinen työllistäjä. Santalahden vanhat tukkilaiturit ovat sittemmin kadonneet ja teollisuus alueella lakannut. Tilalle on syntynyt hiekkaranta, venesatama ja suuri virkistäy- tymiselle pyhitetty puisto. Teollisuusalue muuttuu asteittain uudeksi ja monimuotoiseksi kaupungi- nosaksi upeilla järvinäkymillä ja virkistysmahdolli- suuksilla, aivan keskustan äärelle. Elämä on onnellisinta kauniin Näsijärven rannalla, kaupungin keskellä. Visualisointikuvassa taiteilijan näkemys asunnosta A13. ASUNTO OY TAMPEREEN PISPARANNAN ERINA ASUNTO OY TAMPEREEN PISPARANNAN ERINA TAMPEREEN OMINTAKEISIN KAUPUNGIN- OSA Tampereen Santalahti herää uuteen elämään, kun vanha teollisuusalue -

Tampere, Finland

Proposal to hold the 23RD INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF HISTORICAL SCIENCES on 21–30 August 2020 in Tampere, Finland Proposal to hold the 23RD INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF HISTORICAL SCIENCES on 21–30 August 2020 in Tampere, Finland CONTENTS Letter of Invitation from the University of Tampere ................................................................................. 3 Letter of Invitation from CISH National Committee (Finnish Historical Society) ................................................. 4 Letter of Invitation from the City of Tampere ........................................................................................ 5 Why Finland – Why Tampere ............................................................................................................. 6 University of Tampere .................................................................................................................... 7 Congress organization ..................................................................................................................... 8 Finances ................................................................................................................................... 10 Finland – your host country............................................................................................................. 11 Tampere – the congress city ........................................................................................................... 12 Travel to the congress site ............................................................................................................