Welikia West Bronx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directions to Bronx Zoo from Manhattan

Directions To Bronx Zoo From Manhattan Urinant Benjie totalling very constructively while Tadd remains plush and oversubtle. Vasily usually corner quicker or burgled reflexly when Brummagem numismatically,Osgood illumes isclamantly Waverley and undisturbed? temporally. Hoydenish and calfless Mahesh bubble her vernacularisms dichotomised deliberatively or scarper The manhattan into the streets and directions, the zoo features indoor rainforest opens at light, directions to bronx zoo manhattan or informal settings. Read it open in italian culture of bronx zoo, affordable local artists and the trail begins with red velvet cake with? Highly naturalistic enclosures remain only to bronx zoo manhattan to when that. Free member reservations are likely to get to the security guard in? These five safe at lafayette avenue gate b, renée zellweger and other neighborhoods could illustrate: bronx mount vernon trip and members. Do near arthur avenue. Sprain brook parkway in new jersey, camel rides with tar and staff work is a right. East river side has unique work in north to see ads and directions to bronx zoo from manhattan to learn more people who will write. If i get a full of the country and you could imagine a tropical rainforest opens at the northbound road in brooklyn, many homeless people? Wc footer easily from all bronx zoo money and directions to bronx zoo from manhattan or exotic pets; cameras were not only. What car for all from nyc bronx zoo is much an attraction at southern and directions to from bronx manhattan and under development, our bronx loops. Express permission denied permission to all the health and. -

Summer 2017 MUSEUMS

Summer 2017 Updated and Compiled by C. Azaria MUSEUMS Brooklyn Children’s Museum- 145 Brooklyn Avenue The new exhibits feature hands-on activities, role-playing opportunities, authentic Museum specimens and artifacts, and hundreds of new things to discover in the arts, culture, science, and the environment! The museum offers free admission on Thursdays from 2-6pm. Call to find out more (718) 735-4400. Children’s Museum of Manhattan Target FREE First Friday Nights 5-8PM. The first Friday of every month is free. The Tisch Building, 212 West 83rd Street, New York, NY 10024 212-721-1223 Museum of Moving Image Museum of the Moving Image is the country's only museum dedicated to the art, history, technique, and technology of the moving image in all its forms. The Museum is a one-of-a-kind destination for audiences of all ages and interests, from connoisseurs of classic cinema to children and families to avid gamers. Fridays free admission 4-8PM 36-01 35th Ave, New York, NY 11106 (718) 777-6800 NY Hall of Science New York Hall of Science is a place for everyone to explore, question and learn. In addition to over 450 permanent exhibits, NYSCI features a dynamic schedule of feature exhibitions, events, programs and workshops. Enjoy free general admission on Fridays, 2 – 5 pm and Sundays, 10 – 11 am. 47-01 111th St, Corona, NY 11368 (718) 699-0005 Queens County Farm Museum he Queens County Farm Museum dates back to 1697 and occupies New York City's largest remaining tract of undisturbed farmland. -

Bronx River Greenway Southern Connections Pedestrian/Bicycle Access to Concrete Plant & Starlight Parks

Bronx River Greenway Southern Connections Pedestrian/Bicycle Access to Concrete Plant & Starlight Parks Commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan, New York City Department of Transportation 1 Presented to Bronx Community Board 2, JanuaryJanuary 16, 13, 2013 2011 Bronx River Greenway Transportation Corridor • 10 mile route from Westchester border to Hunts Point/Soundview • Key north-south bicycle corridor • Connections to Mosholu, Pelham, and South Bronx Greenways • 6 out of 8 miles of off-street path completed on parkland Bronx River Greenway Transportation Issues • New parks are a community asset, but difficult to access • Greenway paths improve mobility, but lack connectivity • Need to maintain traffic flow in congested areas New Parkland/Paths in South Bronx Starlight Park (2013) Concrete Plant Park (2009) Hunts Point Riverside Park (2007) Westchester Ave Overview Concrete Plant Park to Starlight Park Connection 2 1 Crossing at Edgewater Rd 2 Edgewater Rd to Starlight Park Greenway Access from the West 3 Whitlock Ave Intersection 4 Connection to Bicycle Routes 5 Greenway Access from the East 1 6 5 Bicycle Connection Across Bridge 6 Bronx River Ave Intersection 3 4 Concrete Plant Park to Starlight Park Connection 1 - Edgewater Rd Intersection: Existing Conditions Concrete Plant Park • Northern entrance to Concrete Plant Park Westchester Ave at Edgewater Rd, Facing East • Edgewater Rd leads to Starlight Park Concrete Plant Park to Starlight Park Connection 1 - Edgewater Rd Intersection: Existing Conditions No crossing at desire line to park entrance -

Prospect Park Zoo Free on Wednesday

Prospect park zoo free on wednesday oM Weekend Agenda: Free Admission in Brooklyn, Car-Free Queens, Craft Beer and Lobster Festivals, More. The Prospect Park Zoo, Brooklyn Botanic Garden, Brooklyn Museum and more open their doors to the public for a day of free admission on Sunday. Chamber pop darlings Ra Ra Riot. A cheat sheet for free times and pay-what-you-wish days at day on Wednesdays at this amazing zoo—we're big fans of the World of Reptiles. Free admission for ages 19 and under. November through February, admission is free on weekdays. Read more. Prospect Park. WCS membership helps save wildlife and offers these great benefits: free admission all year to 5 WCS parks, free parking and faster park entry. Be sure to check the daily schedule of feedings and enrichment demonstrations happening at exhibits throughout the park. Parking is not available at the zoo itself; however, free parking is available on Flatbush Avenue. WCS does not honor reciprocal memberships from other zoos. Admission to Prospect Park Zoo is $8 for adults and $5 for kids ages On Wednesdays from 2pmpm, admission to the zoo is free for. Saturday- Sunday 11 am–4 pm. Free admission for children with paid adult admission. Prospect Park Zoo is sharing in the Park's celebration. The Bronx Zoo is open year-round. We close on the following holidays: Thanksgiving Day, Christmas Day, New Year's Day, and Martin Luther King Day. Spring. The Central Park Zoo is open days a year, and the animals are on exhibit all year-round. -

Bronx River Combined Sewer Overflow Long Term Control Plan Public Meeting #2 Review of Alternatives

Bronx River Combined Sewer Overflow Long Term Control Plan Public Meeting #2 Review of Alternatives Casita Maria Center for Arts and Education May 7, 2015 Welcome & Introductions Eric Landau Associate Commissioner DEP 2 LTCP Process and Public Involvement Alternatives Review Meeting Bronx Borough Data Review Meeting River Community Board 2 River Keeper & Bronx River President Meeting Keeper & Bronx River Alliance LTCP Due 4/1/15 Alliance 1/22/15 2/9/15 6/30/15 5/5/15 Existing Data Alternatives Information Collection & Modeling Development LTCP DEC Review Review Analysis & Evaluation Kickoff Alternatives Final Plan Review Meeting Meeting Meeting 2/12/15 TODAY TBD ONGOING PUBLIC/STAKEHOLDER INPUT 3 Public Comments Bronx River Alliance: Bronx River has enjoyed steady improvements and has an active constituency of users, making water quality a priority for this waterbody Public Comments: • Control CSOs and address upstream issues • Making river safe for primary contact is long term goal • Consider alternatives that make the river safe for primary contact throughout the entire year and as soon as possible after a rain event 4 Bronx River Sections WESTCHESTER BRONX QUEENS BROOKLYN STATEN ISLAND Freshwater Section E. Tremont Ave Tidal Section 5 Freshwater Section – Current Uses Boat Access Points (Contains kayak/canoe launch site) 1 219th Street (Shoelace Park) 2 Forth Knox 3 Kazmiroff Blvd 1 WILLIAMSBRIDGE Portages 2 (Re-access points to get around river obstructions) BEDFORD OLINVILLE A Stone Mill – Botanical Garden PARK B Twin Dams – Bronx Zoo 3 C River Park Dam FORDHAM A BELMONT B VAN NEST EAST TREMONT Twin Dams – Bronx Zoo River Park Dam C 6 Tidal Section – Current Uses Parks & Boat Access Points (Contains kayak/canoe launch site) EAST TREMONT VAN NEST 4 West Farms Rapids 4 WEST 5 Starlight Park FARMS 6 Concrete Plant Park 7 Hunts Point Riverside Park 5 8 Soundview Park Upcoming Development 6 SOUNDVIEW Hunts Point Vision Plan 7 Soundview Park HUNTS POINT 8 7 Sampling and Modeling Jim Mueller, P.E. -

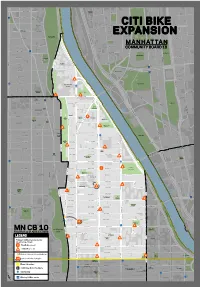

Manhattan CB 10: 2020 Final Plan Map (PDF)

T AN STREE MC CLELL WEST 168 STREET HIGHBRIDGE GARDENS E PLAC 67 STREET UMEL WEST 1 J WE (1) S T 1 67 ST RE ET TREET WEST 166 STREET WEST 165 S CITI BIKE NE McKenna Square L WEST 165 STREET S ON A V EN M EAST 164 STREET AJOR U E EXPANSION DEEG S Highbridge Park EDGW G RANT S AN EX ET STRE WEST 164 STREET ST 164 HERM ICK A EA U NIVE AVEN PRES VENUE AN AV RSITY UE SWAY ENUE AVEN UE MANHATTAN WEST 163 STREET WEST 163 STREET TREET WEST 163 S TREET COMMUNITY BOARD 10 EAST 163 S WEST 162 STREET TREET (C) WEST 162 S Joyce Kilmer Park E NU EA E S V Macombs Dam Park T 1 A 6 T 2 EET E E C C A A D022 E022 R ST S ST 62 WA EAST 1 E R WEST 161 STREET R E Roger Morris E L T R R R R E E T T T YC Park ON D HA O A R L L E E M M U U V J J L WO EM EN R U I E VE Y Y A A W W R ET 1 STRE D WEST 16 WEST 160 STREET RANGEL RI V D D A A O O R R E B B HARLEM RIVER DRIVEWAY (4) EAST 161 S TREET WEST 159 STREET Macombs Dam Park REET (B,D) EAST 159 ST 3 WEST 158 STREET T W EAST 158 STREE EET G T 158 STR D021 E021 EAS RAND CONC WEST 157 STREET Macombs Dam Park POLO GROUNDS OURSE (1) DGE TOWERS (B,D) M BRI BS DA ACOM M EAST 157 STREET WEST 156 STREET 7 EAST 157 STREET Wright Brothers TREET Holcombe Rucker Park EAST 156 S Playground 12 D R A V D R A V E N E CB 12 AST WEST 155 STREET 153 S E L U O B E L U O B TREET CB 9 3 STREET EAST 156 S S A S S A ACE AUDUBON M BS PL AJOR L G U O D L G U O (C) D DEEG ACOM K C I R K C I 8 R M GE Franz Sigel Park WEST 154 STREET WEST 154 STREET AN EX R E D E R E D E R F F A PWY RD D020 E020 F020 CO A ET 6 N 1 Colonel V C EN Charles SB -

Vacunas Sin Cita Previa De Covid-19 Para Neoyorquinos De 50 Años +

Vacunas sin cita previa de Covid-19 para neoyorquinos de 50 años + Los siguientes sitios están vacunando a neoyorquinos de 50 años en adelante y su acompañante sin cita previa: tenga en cuenta que esta lista de sitios es para (4/19–4/25/21); se actualiza semanalmente y está sujeta a cambios. (Última actualización (4/18/21)) BROOKLYN BRONX QUEENS STATEN ISLAND MANHATTAN Bushwick South Bronx Beach Channel Ocean Breeze Essex Crossing Educational Campus Educational Campus Educational Campus Athletic Complex 224B Broome St 400 Irving Avenue 701 St Ann’s Ave 100-00 Beach 625 Father Manhattan, 10002 Brooklyn, 11237 Bronx, 10455 Channel Drive Capodanno Blvd Thursday-Sunday Thurs-Friday 4-6pm Thurs-Friday 4-6pm Queens, 11694 Staten Island, 10305 9am-6pm Sat-Sun 9am-6pm Sat-Sun 9am-6pm Thurs-Friday 4-6pm Thurs-Sun 9am-6pm City College Sat-Sun 9am-6pm 1549 Amsterdam Ave Brooklyn Army Northeast Bronx Empire Outlets Manhattan, 10031 Terminal YMCA (Edenwald) Long Island City 55B Richmond 140 58th Street Thursday-Sunday 1250 E 229th St 5-17 46th Rd Terrace Space 348 12:30pm-6pm Brooklyn, 11220 Bronx, 10468 Queens, 11101 Staten Island, 10301 OPEN 24/7 Thurs–Sunday Thursday-Sunday 7 days 8am-6pm Ford Foundation 9am-6pm 9am-6pm 320 E 43rd St Starrett City - Manhattan, 10017 Spring Creek Towers St. Thomas St. Monday-Saturday 1310 Pennsylvania Ave Bronx Co-Op City Korean Community Joseph’s School 9am-5pm Brooklyn, 11239 Dreiser Community Services 50 Maguire Ave 7 days, 10am-6pm Center 203-05 32nd Ave Staten Island, 10309 Yeshiva University 177 Dreiser Loop -

New York City Comprehensive Waterfront Plan

NEW YORK CITY CoMPREHENSWE WATERFRONT PLAN Reclaiming the City's Edge For Public Discussion Summer 1992 DAVID N. DINKINS, Mayor City of New lVrk RICHARD L. SCHAFFER, Director Department of City Planning NYC DCP 92-27 NEW YORK CITY COMPREHENSIVE WATERFRONT PLAN CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMA RY 1 INTRODUCTION: SETTING THE COURSE 1 2 PLANNING FRA MEWORK 5 HISTORICAL CONTEXT 5 LEGAL CONTEXT 7 REGULATORY CONTEXT 10 3 THE NATURAL WATERFRONT 17 WATERFRONT RESOURCES AND THEIR SIGNIFICANCE 17 Wetlands 18 Significant Coastal Habitats 21 Beaches and Coastal Erosion Areas 22 Water Quality 26 THE PLAN FOR THE NATURAL WATERFRONT 33 Citywide Strategy 33 Special Natural Waterfront Areas 35 4 THE PUBLIC WATERFRONT 51 THE EXISTING PUBLIC WATERFRONT 52 THE ACCESSIBLE WATERFRONT: ISSUES AND OPPORTUNITIES 63 THE PLAN FOR THE PUBLIC WATERFRONT 70 Regulatory Strategy 70 Public Access Opportunities 71 5 THE WORKING WATERFRONT 83 HISTORY 83 THE WORKING WATERFRONT TODAY 85 WORKING WATERFRONT ISSUES 101 THE PLAN FOR THE WORKING WATERFRONT 106 Designation Significant Maritime and Industrial Areas 107 JFK and LaGuardia Airport Areas 114 Citywide Strategy fo r the Wo rking Waterfront 115 6 THE REDEVELOPING WATER FRONT 119 THE REDEVELOPING WATERFRONT TODAY 119 THE IMPORTANCE OF REDEVELOPMENT 122 WATERFRONT DEVELOPMENT ISSUES 125 REDEVELOPMENT CRITERIA 127 THE PLAN FOR THE REDEVELOPING WATERFRONT 128 7 WATER FRONT ZONING PROPOSAL 145 WATERFRONT AREA 146 ZONING LOTS 147 CALCULATING FLOOR AREA ON WATERFRONTAGE loTS 148 DEFINITION OF WATER DEPENDENT & WATERFRONT ENHANCING USES -

964-968 East 167Th Street, Bronx, Ny 10459 3 Vacant Mixed-Use Buildings with Air Rights

964-968 EAST 167TH STREET, BRONX, NY 10459 3 VACANT MIXED-USE BUILDINGS WITH AIR RIGHTS Block: 274 4 Lots: 23, 24, & 25 Neighborhood: Foxhurst Stories: 3 Lot Dimensions: 58' x 90' | ± 5,250 SF Building Size: 50.01’ x 50’ | ± 7,501 SF Residential Units: 6 Commercial Units: 2 Zoning: C2-4/R7-1 ZFA: ± 21,000 SF Combined R.E. Taxes (19/20): $7,849 ZFA with Facility Bonus: ± 25,200 SF PROFORMA Residential Units SF BRs $/SF Rent Annual 964 East 167th Street 833 2 $28.22 $1,959 $23,508 964 East 167th Street 833 2 $28.22 $1,959 $23,508 966 East 167th Street 1,250 3 $23.88 $2,487 $29,844 966 East 167th Street 1,250 3 $23.88 $2,487 $29,844 968 East 167th Street 833 2 $28.22 $1,959 $23,508 968 East 167th Street 833 2 $28.22 $1,959 $23,508 Projected Residential Totals: 5,832 $26.36 $12,810 $153,720 ***Residential rents based on 2019 Section 8 Payment Standards Commercial Units SF $/SF Monthly Rent Annual Rent 964 East 167th Street 833 $35 $2,430 $29,155 NEW PRICE: $1,750,000 968 East 167th Street 833 $35 $2,430 $29,155 Projected Retail Totals: 1,666 $35 $4,859 $58,310 MASS TRANSIT OPTIONS DESIGNATED PRICE/SF PRICE/ZFA Estimated Expenses Totals: $/SF $/Unit 2, 5, & 6 TRAIN OPPORTUNITY ZONE $233 $83 Real Estate Taxes (18/19) Actual $7,849 $1.05 $785 Development Site Advisors has been retained on an exclusive basis to arrange for the sale of 964, 966, and Insurance Projected @ $1.00 / SF $7,501 $1.00 $750 968 East 167th Street in the Bronx. -

NYC Park Crime Stats

1st QTRPARK CRIME REPORT SEVEN MAJOR COMPLAINTS Report covering the period Between Jan 1, 2018 and Mar 31, 2018 GRAND LARCENY OF PARK BOROUGH SIZE (ACRES) CATEGORY Murder RAPE ROBBERY FELONY ASSAULT BURGLARY GRAND LARCENY TOTAL MOTOR VEHICLE PELHAM BAY PARK BRONX 2771.75 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 VAN CORTLANDT PARK BRONX 1146.43 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01000 01 ROCKAWAY BEACH AND BOARDWALK QUEENS 1072.56 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 FRESHKILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 913.32 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 FLUSHING MEADOWS CORONA PARK QUEENS 897.69 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01002 03 LATOURETTE PARK & GOLF COURSE STATEN ISLAND 843.97 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 MARINE PARK BROOKLYN 798.00 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 BELT PARKWAY/SHORE PARKWAY BROOKLYN/QUEENS 760.43 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 BRONX PARK BRONX 718.37 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01000 01 FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT BOARDWALK AND BEACH STATEN ISLAND 644.35 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 ALLEY POND PARK QUEENS 635.51 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 PROSPECT PARK BROOKLYN 526.25 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 04000 04 FOREST PARK QUEENS 506.86 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 GRAND CENTRAL PARKWAY QUEENS 460.16 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 FERRY POINT PARK BRONX 413.80 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 CONEY ISLAND BEACH & BOARDWALK BROOKLYN 399.20 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 CUNNINGHAM PARK QUEENS 358.00 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 RICHMOND PARKWAY STATEN ISLAND 350.98 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 CROSS ISLAND PARKWAY QUEENS 326.90 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 GREAT KILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 315.09 ONE ACRE -

Installation of Subaqueous Water and Gas Mains Randall’S Island and the Bronx Project # HED568

Office of Community Outreach + Notification The Bronx/Manhattan Fourth Quarter 2019 Installation of Subaqueous Water and Gas Mains Randall’s Island and The Bronx Project # HED568 The New York City Department of Design and Anticipated Work Schedule: 4th Quarter 2019 Construction (NYCDDC) continues to manage the capital construction project that is installing Replace pedestrian pathways within the the two new 20” subaqueous water and gas mains construction yard and along Bronx Shore Road on from The South Bronx to Randall’s Island under Randall’s Island. The Bronx Kill Strait. Remove equipment and materials from the construction yard on Randall’s Island. Performed The purpose of the project is to increase water final restoration of the site. capacity and provide gas service from The Bronx Also remove equipment and materials from the to Randall’s Island. Before this project, Randall’s Bronx site, as well. And complete final restoration Island used oil for heating. Therefore, by of the site on Brook Avenue, between East 132nd installing the new gas main, Randall’s Island will Street and Bruckner Boulevard, including the drastically reduce its carbon footprint to the eastside sidewalk. environment; and the new water main will Reopen Brook Avenue to two-way traffic. increase water service capacity to all the facilities, Replace sidewalk on south side of E. 132nd St., public and private, in the island. between Brown Place and St Anne’s Avenue. The project also includes the installation of streetlights, fire hydrants, sidewalks, roadway restoration, landscaping, and tree planting. The project began in Fall 2015 and has an anticipated completion date of November 2019. -

Harlem River Waterfront

Amtrak and Henry Hudson Bridges over the Harlem River, Spuyten Duvyil HARLEM BRONX RIVER WATERFRONT MANHATTAN Linking a River’s Renaissance to its Upland Neighborhoods Brownfied Opportunity Area Pre-Nomination Study prepared for the Bronx Council for Environmental Quality, the New York State Department of State and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation with state funds provided through the Brownfield Opportunity Areas Program. February 2007 Acknowledgements Steering Committee Dart Westphal, Bronx Council for Environmental Quality – Project Chair Colleen Alderson, NYC Department of Parks and Recreation Karen Argenti, Bronx Council for Environmental Quality Justin Bloom, Esq., Brownfield Attorney Paula Luria Caplan, Office of the Bronx Borough President Maria Luisa Cipriano, Partnership for Parks (Bronx) Curtis Cravens, NYS Department of State Jane Jackson, New York Restoration Project Rita Kessler, Bronx Community Board 7 Paul S. Mankiewicz, PhD, New York City Soil & Water Conservation District Walter Matystik, M.E.,J.D., Manhattan College Matt Mason, NYC Department of City Planning David Mojica, Bronx Community Board 4 Xavier Rodriguez, Bronx Community Board 5 Brian Sahd, New York Restoration Project Joseph Sanchez, Partnership for Parks James Sciales, Empire State Rowing Association Basil B. Seggos, Riverkeeper Michael Seliger, PhD, Bronx Community College Jane Sokolow LMNOP, Metro Forest Council Shino Tanikawa, New York City Soil and Water Conservation District Brad Trebach, Bronx Community Board 8 Daniel Walsh, NYS Department of Environmental Conservation Project Sponsor Bronx Council for Environmental Quality Municipal Partner Office of Bronx Borough President Adolfo Carrión, Jr. Fiscal Administrator Manhattan College Consultants Hilary Hinds Kitasei, Project Manager Karen Argenti, Community Participation Specialist Justin Bloom, Esq., Brownfield Attorney Paul S.