Critical Debaters Handbook By: Jackie Massey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Debate Tips & Tricks

Debate Tips & Tricks – Rhode Island Urban Debate League 2019/02/14 623 Home About Us ∠ For Debaters & Coaches ∠ News & Events ∠ Join the Movement Debate Tips & Tricks Partners & Partner Supporters: Schools: Alvarez Central Click Here to download Debate 101: This is a helpful guide to Policy Debate written by Bill & Will Smelko detailing everything 3 you need to know from Rudiments of Rhetoric to Debate Theory. E 5 tips to help you win Juanita every debate round: Sanchez 1. Think as if you were your judge, not yourself. Remember, the only person whose opinion matters at Mount the end of the round is the judge’s, not yours! A Pleasant common mistake everyone in public speaking makes is assuming that because you understand the argument that your audience does as well. Take into account the Paul Cuffee judge’s debate experience before using a lot of debate http://www.riudl.org/debate-tips-tricks/ Page 1 of 4 Debate Tips & Tricks – Rhode Island Urban Debate League 2019/02/14 623 lingo, and make sure you look up at your judge while making a key point. This will both reinforce your argument because of the eye contact you will make, and it will allow you to look for signals from the judge (ie, Woonsocket shaking her head) that she understands you. 2. Always think comparatively. Every argument that you make, at the end of the round, will be compared against something the other team said. If you’re affirmative, for example, you should always be thinking in the mindset of “how does my plan compare to the status quo?” [i.e., doing nothing, what the negative frequently advocates]. -

Page Sub-Page Type Title Learning Goals (Students Will Be Able To...) Attachment One Attachment Two Attachment Three

Page Sub-page Type Title Learning Goals (Students will be able to...) Attachment One Attachment Two Attachment Three Coaching Coaching 10-Minute Speaker Short Activities Resources Resources Roles Practice Coaching Before, Coaching Coaching Best Practice During, and After Resources Resources Document Tournaments Coaching Coaching Best Practice Coaching Resources Resources Document Fundamentals Coaching Coaching Best Practice Coaching the Resources Resources Document Affirmative Coaching Coaching Best Practice Coaching the Resources Resources Document Negative Coaching Coaching Glossary-of-Debate- Document Resources Resources Terms Coaching Coaching Best Practice Ideas for Culture and Resources Resources Document Norm Building Coaching Coaching Quick Speech Short Activities Resources Resources Activities Short Speaking Coaching Coaching Short Activities Games for the First Resources Resources Few Practices Coaching Student 1NC Block Template Note Sheet Resources Resources for Topicality Coaching Student Template 8.5 11 Flowsheet Resources Resources Coaching Student Template 8.5 14 Flowsheet Resources Resources Coaching Student Debate Observer Note Sheet Resources Resources Debrief Worksheet Coaching Student Debate Terms Document Resources Resources Glossary Coaching Student Guide for Novice Document Resources Resources Policy Debaters Coaching Student Topicality Note Sheet Resources Resources Worksheet Tournament 1 Coaching Student Checklist Checklist for Resources Resources Students Coaching Coach IT Video Edit Student Records Resources Introduction to Coaching Coach IT Video Speechwire for Resources Coaches Coaching Registering for Coach IT Video Resources Tournaments Coaching Coach IT Video Roster Management Resources Team Reporting Coaching Coach IT Video from Tabroom to Resources Your UDL - directly respond to specific arguments. - generate arguments under time constraints. Debate Lesson Argumentation Lesson Chain Debates Library ▪ Respond to oral arguments with direct refutation. -

Beg. CX Robertson-Markham

Jonathan Robertson, Sudan H.S. and James Markham, Anton H.S. An Introduction to UIL CX Debate UIL WTAMU SAC - September 23rd, 2017 Beatriz Melendez and Jose Luis Melendez, 2-A UIL CX Debate State Champions 2016 “You can do it!” -The Waterboy Introduction - Brief video as students and coaches enter: (Debate class video) What is CX Debate? Policy debate. Policy = evidence. Lots of evidence. This event will change your life. One student’s story that ends submerged. So, are you ready to “Suit Up”? The Resolution: Resolved: The United States federal government should substantially increase its funding and/or regulation of elementary and/or secondary education in the United States. “Debate is blood sport, only your weapons are words.” 2 - Denzel Washington in The Great Debaters The Speeches and their Times: 1st Affirmative Constructive (1AC=8 min) CX (3 min by the 2NC) (never use prep time before CX periods) 1st Negative Constructive (1NC=8 min) CX (3 min by the 1AC) 2nd Affirmative Constructive (2AC=8 min) CX (3 min by the 1NC) 2nd Negative Constructive (2NC=8 min) (2NC + 1NR = Negative Block) CX (3 min by the 2AC) 1st Negative Rebuttal(1NR=5 min) 1st Affirmative Rebuttal (1AR=5 min) 2nd Negative Rebuttal (2NR=5 min) 2nd Affirmative Rebuttal (2AR=5 min) Each team receives 8 minutes of prep time that may be used according to their strategy. Citation of evidence Evidence must be contiguous. And, citations done correctly, i.e.: Frank, 2015 [Walter M. Frank (legal scholar, attorney), “Individual Rights and citation → the Political Process: A Proposed Framework for Democracy Defining Cases,” 3 Southern University Law Review 35:47, Fall, 2015, p. -

Finding Your Voice

FINDING YOUR VOICE FINDING YOUR VOICE A Comprehensive Guide to Collegiate Policy Debate Allison Hahn Taylor Ward Hahn Marie-Odile N. Hobeika International Debate Education Association New York, London & Amsterdam Published by: International Debate Education Association 105 East 22nd Street New York, NY 10010 Copyright © 2013 by Allison Hahn, Taylor Ward Hahn, and Marie-Odile N. Hobeika This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hahn, Allison. Finding your voice : a comprehensive guide to collegiate policy debate / Allison Hahn, Taylor Ward Hahn, Marie-Odile N. Hobeika. pages cm ISBN 978-1-61770-051-4 1. Debates and debating. I. Hahn, Taylor Ward. II. Hobeika, Marie-Odile N. III. Title. PN4181.H24 2013 808.53--dc23 2012042433 Design by Kathleen Hayes Printed in the USA CONTENTS Preface ............................................... vii Chapter 1: Basics of Policy Debate ...................... 1 Chapter 2: The Policy Debate Squad .................... 11 Chapter 3: The Topic Process ........................... 16 Chapter 4: Arguments ................................. 22 Chapter 5: Evidence ................................... 35 Chapter 6: Responsibilities of the Affirmative and Negative .............................................. 59 Chapter 7: Speaking and Flowing ....................... 67 Chapter 8: Speeches ................................... 76 Chapter 9: Cross-Examination ......................... 97 Chapter -

Is a Genuinely Sustainable, Locally-Led, Politically-Smart

Is a genuinely sustainable, locally-led, politically-smart approach to economic governance and Business Environment Reform possible? Lessons from 10 years implementing ENABLE in Nigeria Gareth Davies, November 2017 Lessons from 10 years of ENABLE in Nigeria 1 Contents Introduction 4 A. What does it mean to be sustainable, locally-led, and politically-smart? 6 B. How sustainable, locally-led, and politically-smart are mainstream approaches? 10 C. How was ENABLE different, in approach and in practice? 13 D. What did ENABLE achieve, and what difference did the approach make? 22 E. How do donors help (and hinder) implementation of a genuinely sustainable, locally-led, politically-smart approach? 31 Conclusions 34 References 35 The author would like to thank the entire ENABLE1 and ENABLE2 team, particularly Kevin Conroy (the ENABLE2 Team Leader), and the Senior Component Managers – Adenike Mantey, Abosede Paul-Obameso, Helen Bassey, and Habiba Jambo – without whose hard work and dedication the sucacess of ENABLE1 and 2, and therefore this paper, would not have been possibale. Special thanks also goes to David Elliott and Gavin Anderson, who take a good deal of credit for designing, shaping, and guiding the ENABLE programme over the years. Thanks also to everyone who commented on drafts of this paper, including David Elliott, Kevin Conroy, Kevin Seely, and Dan Hetherington. The views expressed in this paper are the author’s own and do not reflect the views of Adam Smith International or the UK Department for International Development. 2 Glossary -

Badgerland Pref Book

James Madison Memorial and Middleton High Schools proudly host Badgerland Debate Tournament November 13-14, 2015 Judge Philosophy Book Updated as of 9:35 pm, 11/12/2015 LINCOLN-DOUGLAS JUDGES .............................................................................................................................. 4 Bailey, Kevin ............................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Beaver, Zack ............................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Berger, Marcie ........................................................................................................................................................................ 7 Burdt, Lauren .......................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Dean, John .............................................................................................................................................................................. 12 Dempsey, Richard ............................................................................................................................................................... 13 Fischer, Jason ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

Niles Debate Curriculum Guide

Debate SO3D01 Curriculum Guide Niles Township High Schools, District 219 Ms. Katie Gjerpen Mr. Eric Oddo Table of Contents: Department Structure……………………………………3 Learning Targets…………………………………………4 Syllabus…………………………………………………..7 Pacing Guide…………………………………………….14 Instructional Materials…………………………………...26 Assessment Materials…………………………………...122 2 Department Structure: 3 Debate Learning Targets: Learning Target (1) - Common Core Skills A. I can read and interpret an historical document. B. I can recognize the difference between facts and opinions. C. I can write and defend a thesis. D. I can write a coherent paragraph using a claim, evidence, and a warrant. E. I can interpret maps, charts, graphs, and political cartoons. F. I can connect facts to construct meaning and make logical inferences. G. I can take notes to organize historical content. H. I can utilize the political spectrum to analyze historical events. Learning Target (2)-Advanced Research A. I can use electronic resources to find debate evidence. B. I can compile debate evidence into block format so it can be used during a round. C. I can identify quality sources and find qualifications of authors with ease. Learning Target (3)-The Affirmative A. I can explain the major components of the 1AC. B. I can construct a 1AC that places the Affirmative in strategic position over the Negative. C. I can extend case arguments in the 2AC, 1AR and 2AR effectively. D. I can describe why the impacts of the Affirmative outweigh the impacts of the Negative disadvantages, counter plan net benefits and kritik impacts. E. I can utilize Affirmative theory arguments to my advantage and to the Negative’s disadvantage during a debate round. -

Hegemony Advantage

Middle School Packet 10 Hegemony Advantage - SCS Impact Framing Extinction from nuclear war dwarfs all other impact calculus – reducing nuclear risk is morally required Jonathan Schell, 2000, Fate of the Earth, pp. 93-96, Jonathan Schell was an American author and was a fellow at the Institute of Politics at the John F. Kennedy School of Government and a fellow at the Kennedy School's Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics, and Public Policy. In 2003, he was a visiting lecturer at Yale Law School, and in 2005, a Distinguished Visiting Fellow at Yale's Center for the Study of Globalization, whose work primarily dealt with campaigning against nuclear weapons, https://books.google.com/books?id=tYKJsAEs1oQC&printsec=frontcover&dq=jonathan+schell+fate+of+the+earth&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEw j2p6fzmbXOAhXJCMAKHZsID_QQ6AEIHjAA#v=onepage&q=to%20say%20that%20human%20extinction&f=false To say that human extinction is a certainty would, of course, be a misrepresentation – just as it would be a misrepresentation to say that extinction can be ruled out. To begin with, we know that a holocaust may not occur at all. If one does occur, the adversaries may not use all their weapons. If they do use all their weapons, the global effects in the ozone and elsewhere, may be moderate. And if the effects are not moderate but extreme, the ecosphere may prove resilient enough to withstand them without breaking down catastrophically. These are all substantial reasons for supposing that mankind will not be extinguished in a nuclear holocaust, or even that extinction in a holocaust is unlikely, and they tend to calm our fear and to reduce our sense of urgency. -

Debater Developmental Benchmarks

Debater Developmental Benchmarks Growth of a CDL Debater: Key Benchmarks In order to measure the qualitative growth a CDL debater, the Chicago Debate League uses designated benchmarks for each year of a CDL debater's development. These benchmarks help CDL coaches and administrators design teaching strategies and methods, and help them assess the progress of individual debaters and of debate teams as a whole. Qualitative benchmarks also assist the CDL in balancing the crucial focus on the scope and breadth of programming - student participation metrics - with results-oriented and sustained commitment to programming that is qualitatively meaningful, has depth, is consistent with broader standards of rigor within the broader context of high school competitive academic debate, and perhaps most importantly, produces measurable learning outcomes aligned with broader academic goals. The numbers attached to each benchmark are for reference purposes and do not imply sequential ordering to their teaching or learning, though year two benchmarks build on year one benchmarks, and likewise year three/four benchmarks build on what should be learned by debaters in their the first two years. Year One Benchmarks Debate Round Mechanics (1) Speeches, cross-examination, prep time Debater understands when it is their turn to speak and for how long; understands when to ask/answer cross-examination questions; understands prep time (how much available, use) (2) Role of the judge, function of the ballot Debater understands the conduct, limitations, and jurisdiction -

DO NOT LOSE THIS BOOKLET! Bring It with You to Each Day of Competition

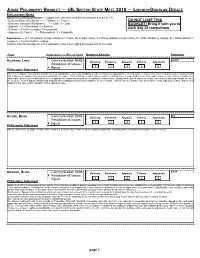

JUDGE PHILOSOPHY BOOKLET — UIL SPEECH STATE MEET 2018 — LINCOLN-DOUGLAS DEBATE EXPLANATORY NOTES Numerical ranking questions — judges were asked to rank the following on a scale of 1-5: • Delivery (Rate of Delivery) — 1 = Slower, 5 = Faster DO NOT LOSE THIS • Evidence (Amount of Evidence) — 1 = Little, 5 = Lots BOOKLET! Bring it with you to • Appeals — 1 = Emotional, 5 = Factual • Criteria — 1 = Unnecessary, 5 = Essential each day of competition. • Approach (to Topic) — 1 = Philosophical, 5 = Pragmatic Experience — G = LD debater in high school, H = Coach LD in high school, A = Policy debater in high school, D = NDT debater in college, E = CEDA debater in college, F = Coach CEDA in college Debaters may ask any judge for a brief explanation of his or her judging philosophy prior to the round. JUDGE COMM. SKILLS VS. RES. OF ISSUES NUMERICAL RANKINGS EXPERIENCE HADF ALDERSON, LINDA Communication Skills Delivery Evidence Appeals Criteria Approach Resolution of Issues Equal 4 5 4 5 5 Philosophy Statement LD is value debate. The debater should focus on supporting a value and weighing it with a criterion as opposed to a second value. I expect well structured persuasive communication with evidence to support all assertions, including the value. Both affirmative and negative debaters should have a value and criteria and explain how the case filters through those arguments. Both debaters should refute their opponents' arguments as well as extending their own cases. I judge as a critic of argument in that each student should persuade me as to the credence of their arguments through analysis and organization as well as refutation. -

Judge Philosophy Booklet — Uil Cx Debate State Tournament 2016

JUDGE PHILOSOPHY BOOKLET — UIL CX DEBATE STATE TOURNAMENT 2016 — 1A, 2A, 3A EXPLANATORY NOTES Numerical ranking questions — judges were asked to rank the following on a scale of 1-5: • Qty. Arg. (Quantity of Arguments) — 1 = Limited, 5 = Unlimited DO NOT LOSE THIS BOOKLET! • T (Topicality) — 1 = Rarely Vote On, 5 = Vote On Often • CP (Counterplans) — 1 = Unacceptable, 5 = Acceptable Bring it with you to each day of • DA (Disadvantages) — 1 = Not Essential, 5 = Essential competition. • Cond. Arg. (Conditional Arguments) — 1 = Unacceptable, 5 = Acceptable • Kritiks — 1 = Unacceptable, 5 = Acceptable Experience — A = policy debater in high school, B = coach policy debate in high school, C = coach policy debate in college, D = college NDT debate, E = college CEDA debate, J = college LD debate, K = college parliamentary debate IMPORTANT NOTE: Some judges’ philosophy statements may be too long to fit completely in the box, and there may be some new judges who do not appear in this booklet. New judges and expanded printouts for those with longer philosophy statements will be posted in the assembly room. Debaters may ask any judge for a brief explanation of his or her judging philosophy prior to the round. COMM. SKILLS VS. QTY. VS. QUALITY RES. OF ISSUES OF EVIDENCE JUDGE PARADIGM NUMERICAL RANKINGS EXPERIENCE ABRAHA, WEGAHTA Tabula rasa Comm. Skills Quantity Qty. Arg. T CP DA Cond. Arg. Kritiks ADE Res. Issues Quality 5 4 5 5 5 5 Philosophy Statement Equal Equal tabula rasa is probably the best way to describe it, i default to an offense/defense paradigm unless a different framing is presented in It's UIL, that being said, I dont' mind speed as the debate. -

Public Forum Curriculum

Atlanta Urban Debate League Public Forum Curriculum Find us online at: youtube.com/atlantadebate facebook.com/atlantadebate instagram.com/atlantadebate twitter.com/atlantadebate Public Forum Curriculum Atlanta Urban Debate League Table of Contents Contents Table of Contents .............................................................................................................................................. 2 What Is Public Forum? ...................................................................................................................................... 3 What’s New?: An Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 3 What Is Public Forum? ................................................................................................................................ 3 Who Should Debate In Public Forum? ........................................................................................................ 3 Which Is Better: Policy or Public Forum? .................................................................................................... 3 What’s Different?: Policy v. Public Forum ....................................................................................................... 4 Topic Release (Calendar) ........................................................................................................................... 5 Sample Resolution .....................................................................................................................................