The Salter in This Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Survey of Anadromous Fish Passage in Coastal Massachusetts

Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Technical Report TR-16 A Survey of Anadromous Fish Passage in Coastal Massachusetts Part 2. Cape Cod and the Islands K. E. Reback, P. D. Brady, K. D. McLaughlin, and C. G. Milliken Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Department of Fish and Game Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Commonwealth of Massachusetts Technical Report Technical May 2004 Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Technical Report TR-16 A Survey of Anadromous Fish Passage in Coastal Massachusetts Part 2. Cape Cod and the Islands Kenneth E. Reback, Phillips D. Brady, Katherine D. McLauglin, and Cheryl G. Milliken Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Southshore Field Station 50A Portside Drive Pocasset, MA May 2004 Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Paul Diodati, Director Department of Fish and Game Dave Peters, Commissioner Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Ellen Roy-Herztfelder, Secretary Commonwealth of Massachusetts Mitt Romney, Governor TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 2: Cape Cod and the Islands Acknowledgements . iii Abstract . iv Introduction . 1 Materials and Methods . 1 Life Histories . 2 Management . 4 Cape Cod Watersheds . 6 Map of Towns and Streams . 6 Stream Survey . 8 Cape Cod Recommendations . 106 Martha’s Vineyard Watersheds . 107 Map of Towns and Streams . 107 Stream Survey . 108 Martha’s Vineyard Recommendations . 125 Nantucket Watersheds . 126 Map of Streams . 126 Stream Survey . 127 Nantucket Recommendations . 132 General Recommendations . 133 Alphabetical Index of Streams . 134 Alphabetical Index of Towns . .. 136 Appendix 1: List of Anadromous Species in MA . 138 Appendix 2: State River Herring Regulations . 139 Appendix 3: Fishway Designs and Examples . 140 Appendix 4: Abbreviations Used . 148 ii Acknowledgements The authors wish to thank the following people for their assistance in carrying out this survey and for sharing their knowledge of the anadromous fish resources of the Commonwealth: Brian Creedon, Tracy Curley, Jack Dixon, George Funnell, Steve Kennedy, Paul Montague, Don St. -

E. Fisheries and Wildlife

E. Fisheries and Wildlife Until recent decades, the vast majority of Mashpee’s territory was the domain not of man, but of beast. Our woods were only occasionally broken by a roadway, or a few homes, or a farmer’s fields. The hunting was good. Our clear lakes were famous for their fishing. Our streams flowed clean to pristine coastal bays teeming with fish and shellfish that helped feed and support many families. Much has changed with the explosive development of the last fifty years, and much of our wildlife has disappeared along with the natural habitat that supported it. However, much remains for our enjoyment and safekeeping. In this section we will look at Mashpee’s fish and shellfish, its mammals, birds and insects, important wildlife movement corridors and those species living in our town which are among the last of their kind. 1. Finfish Mashpee hosts four types of fin fisheries: fresh water ponds, rivers and streams, estuaries and coastal ponds and the open ocean. Our four large ponds provide some of the best fishing in the state. 203-acre Ashumet Pond, 317- acre Johns Pond and 729-acre Mashpee-Wakeby Pond are all cold water fisheries stocked with brown, brook and rainbow trout. In the last century, such famous anglers as Daniel Webster, President Grover Cleveland and the famous actor Joseph Jefferson looked forward to their fishing expeditions to Mashpee, while local residents looked forward to the income provided serving as guides to those and other wealthy gentlemen. Ashumet and Johns Ponds are also noted for their smallmouth bass, while Mashpee-Wakeby provides not only the smallmouth, but also chain pickerel, white perch and yellow perch. -

Massachusetts Estuaries Project

Massachusetts Estuaries Project Linked Watershed-Embayment Model to Determine Critical Nitrogen Loading Thresholds for Popponesset Bay, Mashpee and Barnstable, Massachusetts University of Massachusetts Dartmouth Massachusetts Department of School of Marine Science and Technology Environmental Protection FINAL REPORT – SEPTEMBER 2004 Massachusetts Estuaries Project Linked Watershed-Embayment Model to Determine Critical Nitrogen Loading Thresholds for Popponesset Bay, Mashpee and Barnstable, Massachusetts FINAL REPORT – SEPTEMBER 2004 Brian Howes Roland Samimy David Schlezinger Sean Kelley John Ramsey Jon Wood Ed Eichner Contributors: US Geological Survey Don Walters, and John Masterson Applied Coastal Research and Engineering, Inc. Elizabeth Hunt and Trey Ruthven Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection Charles Costello and Brian Dudley (DEP project manager) SMAST Coastal Systems Program Paul Henderson, George Hampson, and Sara Sampieri Cape Cod Commission Brian DuPont Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection Massachusetts Estuaries Project Linked Watershed-Embayment Model to Determine Critical Nitrogen Loading Thresholds for Popponesset Bay, Mashpee and Barnstable, Massachusetts Executive Summary 1. Background This report presents the results generated from the implementation of the Massachusetts Estuaries Project’s Linked Watershed-Embayment Approach to the Popponesset Bay System a coastal embayment within the Towns of Mashpee and Barnstable, Massachusetts. Analyses of the Popponesset Bay System was performed to assist the Towns with up-coming nitrogen management decisions associated with the Towns’ current and future wastewater planning efforts, as well as wetland restoration, anadromous fish runs, shell fishery, open-space, and harbor maintenance programs. As part of the MEP approach, habitat assessment was conducted on the embayment based upon available water quality monitoring data, historical changes in eelgrass distribution, time-series water column oxygen measurements, and benthic community structure. -

Annual Report 2018

Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife 2018 Annual Report 147 Annual Report 2018 Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife Jack Buckley Director (July 2017–May 2018) Mark S. Tisa, Ph.D., M.B.A. Acting Director (May–June 2018) 149 Table of Contents 2 The Board Reports 6 Fisheries 42 Wildlife 66 Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program 82 Information & Education 95 Archivist 96 Hunter Education 98 District Reports 124 Wildlife Lands 134 Federal Aid 136 Staff and Agency Recognition 137 Personnel Report 140 Financial Report Appendix A Appendix B About the Cover: MassWildlife staff prepare to stock trout at Lake Quinsigamond in Worcester with the help of the public. Photo by Troy Gipps/MassWildlife Back Cover: A cow moose stands in a Massachusetts bog. Photo by Bill Byrne/MassWildlife Printed on Recycled Paper. ELECTRONIC VERSION 1 The Board Reports Joseph S. Larson, Ph.D. Chairperson Overview fective April 30, 2018, and the Board voted the appoint- ment of Deputy Director Mark Tisa as Acting Director, The Massachusetts Fisheries and Wildlife Board con- effective Mr. Buckley’s retirement. The Board -mem sists of seven persons appointed by the Governor to bers expressed their gratitude and admiration to the 5-year terms. By law, the individuals appointed to the outgoing Director for his close involvement in develop- Board are volunteers, receiving no remuneration for ing his staff and his many accomplishments during his their service to the Commonwealth. Five of the sev- tenure, not only as Director but over his many years as en are selected on a regional basis, with one member, Deputy Director in charge of Administration, primarily by statute, representing agricultural interests. -

Body of Report

Streamflow Measurements, Basin Characteristics, and Streamflow Statistics for Low-Flow Partial-Record Stations Operated in Massachusetts from 1989 Through 1996 By Kernell G. Ries, III Abstract length; mean basin slope; area of surficial stratified drift; area of wetlands; area of water bodies; and A network of 148 low-flow partial-record mean, maximum, and minimum basin elevation. stations was operated on streams in Massachusetts Station descriptions and calculated streamflow during the summers of 1989 through 1996. statistics are also included in the report for the 50 Streamflow measurements (including historical continuous gaging stations used in correlations measurements), measured basin characteristics, with the low-flow partial-record stations. and estimated streamflow statistics are provided in the report for each low-flow partial-record station. Also included for each station are location infor- INTRODUCTION mation, streamflow-gaging stations for which flows were correlated to those at the low-flow Streamflow statistics are useful for design and operation of reservoirs for water supply and partial-record station, years of operation, and hydroelectric generation, sewage-treatment facilities, remarks indicating human influences of stream- commercial and industrial facilities, agriculture, flows at the station. Three or four streamflow mea- maintenance of streamflows for fisheries and wildlife, surements were made each year for three years and recreational users. These statistics provide during times of low flow to obtain nine or ten mea- indications of reliability of water resources, especially surements for each station. Measured flows at the during times when water conservation practices are low-flow partial-record stations were correlated most likely to be needed to protect instream flow and with same-day mean flows at a nearby gaging other uses. -

2019 Annual Report

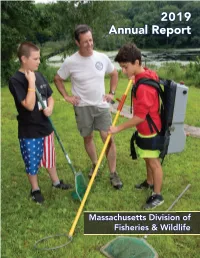

2019 Annual Report Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife 161 Annual Report 2019 Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife Mark S. Tisa, Ph.D., M.B.A. Director 163 Table of Contents 2 The Board Reports 6 Fisheries 60 Wildlife 82 Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program 98 Information & Education 114 Hunter Education 116 District Reports 138 Wildlife Lands 149 Archivist 150 Federal Aid 152 Personnel Report 154 Financial Report Front Cover: Jim Lagacy, MassWildlife Angler Education Coordinator, teaches Fisheries Management to campers at the Massachusetts Junior Conservation Camp in Russell. Photo by Troy Gipps/MassWildlife Back Cover: A blue-spotted salamander (Ambystoma laterale), a state-listed Species of Special Concern, rests on an autumn leaf at the Wayne F. MacCallum Wildlife Management Area in Westborough. Photo by Troy Gipps/MassWildlife Printed on Recycled Paper. 1 The Board Reports Joseph S. Larson, Ph.D. Chairperson Overview 32 years of experience with MassWildlife, including as the The Massachusetts Fisheries and Wildlife Board consists Assistant Director of Fisheries for 25 years; as the Depu- of seven persons appointed by the Governor to 5-year ty Director of the agency for the previous 3 years (March terms. By law, the individuals appointed to the Board are 2015—April 2018); and most recently as its Acting Director, volunteers, receiving no remuneration for their service to effective April 30, 2018. The Fisheries and Wildlife Board ap- the Commonwealth. Five of the seven are selected on a pointed Director Tisa because of his lifelong commitment to regional basis, with one member, by statute, representing wildlife and fisheries conservation and his excellent record agricultural interests. -

Town of Mashpee, Popponesset Bay, & Waquoit Bay East Watersheds

Town of Mashpee, Popponesset Bay, & Waquoit Bay East Watersheds TM Nitrex Technology Scenario Plan Submitted to: Town of Mashpee Submitted by: Sewer Commission 16 Great Neck Road North Mashpee, MA 02469 August 1, 2008 Town of Mashpee Sewer Commission August 1, 2008 Table of Contents Executive Summary........................................................................................................ 1 1 Objective................................................................................................................ 10 2 Background............................................................................................................ 10 2.1 Wastewater Flows .......................................................................................... 11 2.2 Hydrogeology ................................................................................................. 13 3 Needs Definition .................................................................................................... 20 3.1 Data Management - Methodology .................................................................. 20 3.2 Planning Area Parcel Summary...................................................................... 31 3.3 Nitrogen Loading and TMDLs......................................................................... 33 3.3.1 Data Overview......................................................................................... 34 3.3.2 Popponesset Bay Nitrogen Removal Requirements ............................... 38 3.3.3 East Waquoit Bay Nitrogen -

General Recommendations 1. with a Small Number of Exceptions, The

General Recommendations 1. With a small number of exceptions, the important river herring spawning/nursery habitats on coastal streams have been made accessible through the construction of fishways. Many of these structures have become deteriorated and are often of obsolete design. The emphasis of future work should be on the replacement of these fish ladders in order to preserve or augment the populations they serve rather than to create new populations by accessing minor habitats. 2. Most river herring fisheries are under local control through the authority granted by Section 94 of Chapter 130. Many towns having this control, however, are unaware that approval of the Director of the Division of Marine Fisheries is required by the statute and often change their regulations without consulting DMF. In order to insure biologically sound and legally valid local management, the Director should inform cities and towns of this condition and request them to submit current regulations and subsequent changes for approval. 3. River herring passage issues have dealt primarily with upstream migration of adults. Downstream passage of adults and more importantly juveniles has been largely ignored and, in some systems, may be an important limiting factor in population productivity. Future work should take this into consideration and place appropriate emphasis on this phase of the life cycle and the problems which are associated with it. 4. Large numbers of juvenile herring are killed each year due to cranberry bog operations. A simple, inexpensive screening system has been developed which will prevent most of these losses. Despite publicizing the availability of this system through industry media, growers have been reluctant to utilize it. -

A Report Upon the Alewife Fisheries of Massachusetts

4/27/2018 www.westtisbury-ma.gov/Documents/Mill-Brook-docs/Appendix A Doc 20 Belding-alewives-1921.txt Web Video Texts Audio Software About Account TVNews OpenLibrary Full text of "A report upon the alewife fisheries of Massachusetts. Division of fisheries and game. Department of conservation" A REPORT UPON THE ALEWIFE FISHERIES OF MASSACHUSETTS Division of Fisheeibs and Game Depaetment of Conseevation BOSTON WRIGHT & POTTER PRINTING CO., STATE PRINTERS 32 DERNE STREET 1921 New York State College of Agriculture At Cornell University Ithaca, N. Y. Library Cornell University Library SH 167.A3M41 A report upon the alewife fisheries of M 3 1924 003 243 999 Cornell University Library There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924003243999 REPORT UPON THE ALEWIFE FISHERIES OF MASSACHUSETTS. Part I, INTRODUCTION. An important part of the work of a progl-essive State fish and game commission is the investigation of natural resources for the purpose of determining proper and effective methods of conserving these valuable assets for the benefit of the public. For the past fifteen years the Massachusetts Division of Fish- eries and Game has been investigating such economic prob- lems, one of which, the alewife fishery, furnishes an excellent illustration of the practical value of biological study in the preservation of a commercial fishery. Importance.- — Since the disappearance of the shad, the ale- wife, or branch herring (Pomolobiis pseudoharengus), the most abundant food fish inhabiting the rivers of the Atlantic coast, has become commercially the most valuable anadromous fish in Massachusetts. -

Jo Ann-Herring-2020-MA

Volunteer Counts of River Herring: Why and How? March 2020 Jo Ann Muramoto, Ph.D. MassBays Regional Coordinator, Cape Cod Association to Preserve Cape Cod 482 Main Street Dennis, MA 02638 River Herring – Two Anadromous Species Source: Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries. Why do we care about river herring? (Food!) Striped Bass Bluefish Zooplankton People Blueback Herring Atlantic cod Alewife Other species that eat herring: osprey, bald eagle, great blue heron, gulls, terns, cormorants, other seabirds, seals, whales, river otter, fox, raccoon, skunk, weasel, fisher, turtles, tuna, haddock, halibut, American eel, brook trout, rainbow trout, brown trout, smallmouth and largemouth bass, white and yellow perch. Slide modiFied From Abigail Franklin’s slide RegionalWhy Declineis counting of River river Herring herring Populations important? Pounds of River Herring Landed 1950-2004 River Intercept Fisheries Causes of decline: • Barriers to passage • Water withdrawals • Habitat loss • Water pollution • Poaching • Predation • Overfishing • 2017 – near historic lows Data from National Marine Fisheries Service – adapted from slide by Abigail Franklin What’sWhy Being is Done: counting Ban on Fishing, river 2006 herring - ongoing important? Pounds of River Herring Landed 1950-2004 NOAA National Marine Fisheries River InterceptService: Fisheries • Approved 12-mile ban on mid-water trawling For herring From Connecticut to Canadian border; • Approved 20-mile ban east oF Cape Cod; • New catch limits set at 80% of sustainable levels • Requires ongoing -

Massachusetts Estuaries Project

Massachusetts Estuaries Project Linked Watershed-Embayment Model to Determine Critical Nitrogen Loading Thresholds for Popponesset Bay, Mashpee and Barnstable, Massachusetts University of Massachusetts Dartmouth Massachusetts Department of School of Marine Science and Technology Environmental Protection FINAL REPORT – SEPTEMBER 2004 Massachusetts Estuaries Project Linked Watershed-Embayment Model to Determine Critical Nitrogen Loading Thresholds for Popponesset Bay, Mashpee and Barnstable, Massachusetts FINAL REPORT – SEPTEMBER 2004 Brian Howes Roland Samimy David Schlezinger Sean Kelley John Ramsey Jon Wood Ed Eichner Contributors: US Geological Survey Don Walters, and John Masterson Applied Coastal Research and Engineering, Inc. Elizabeth Hunt and Trey Ruthven Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection Charles Costello and Brian Dudley (DEP project manager) SMAST Coastal Systems Program Paul Henderson, George Hampson, and Sara Sampieri Cape Cod Commission Brian DuPont MASSACHUSETTS ESTUARIES PROJECT ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Massachusetts Estuaries Project Technical Team would like to acknowledge the contributions of the many individuals who have worked tirelessly for the restoration and protection of the critical coastal resources of the Popponesset Bay System. Without these stewards and their efforts, this project would not have been possible. First and foremost is the significant time and effort in data collection and discussion spent by members of the Popponesset Bay Water Quality Monitoring Program and the Cotuit Waders. These individuals gave of their time to collect water quality samples from this system from 1997 – 2003, without this information the present analysis would not have been possible. Similarly, many in the Towns of Mashpee and Barnstable worked diligently on this effort, the Mashpee Waterways Commission, Mashpee Shellfish Department, Mashpee Watershed Nutrient Management Committee, Mashpee Sewer Commission, and Mashpee Board of Selectman and the Barnstable Nutrient Management Group. -

Cape Cod Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) Amendment

Cape Cod Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) Cape Cod Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) AMENDMENT Federal Fiscal Years 2013–2016 Endorsement: March 4, 2013 Administrative Adjustment: April 22, 2013 Orleans, Route 28 and Route 6A Falmouth, Jones Road at Route 28 Cape Cod Metropolitan Planning Organization Cape Cod Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) Amendment Federal Fiscal Years 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016 (October 1, 2012 – September 30, 2016) January—March 2013 Prepared by the Cape Cod Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) Members: Richard A. Davey, Secretary / Chief Executive Officer, Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) Francis A. DePaola, P.E., Administrator, Massachusetts Department of Transportation, Highway Division John D. Harris, Chairman, Cape Cod Commission Ronald J. Bergstrom, Chairman, Cape Cod Regional Transit Authority William Doherty, MPO Representative, Barnstable County Commissioners Jason Steiding, Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe Debra S. Dagwan, President, Barnstable Town Council Michael Richardson, Mashpee Selectmen, for Sub-Region A: Bourne, Falmouth, Mashpee, Sandwich Curtis Sears, Yarmouth Selectmen, for Sub-Region B: Dennis and Yarmouth Sims McGrath, Orleans Selectmen, for Sub-Region C: Brewster, Chatham, Harwich, Orleans Austin Knight, Provincetown Selectmen, for Sub-Region D: Eastham, Wellfleet, Truro, Provincetown MPO Ex-Officio Members: Pamela S. Stephenson, Division Administrator - Non-Voting, Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) Mary Beth Mello, Regional Administrator - Non-Voting, Region I Office, Federal Transit Administration (FTA) Lawrence T. Davis, Army Corps of Engineers / Cape Cod Canal Wayne Lamson, Woods Hole, Martha's Vineyard, and Nantucket Steamship Authority (SSA) George Price, National Park Service / Cape Cod National Seashore (CCNS) George Allaire, P.E., Cape Cod Joint Transportation Committee and the Cape Cod Joint Transportation Committee George Allaire, P.E., Chairman, Yarmouth Joseph Rodricks, P.E., Vice-Chairman, Dennis Cape Cod Commission TIP Staff Contact: Priscilla N.