Offensive Women: Women in Combat in the Red Army in the Second

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Utopian Visions of Family Life in the Stalin-Era Soviet Union

Central European History 44 (2011), 63–91. © Conference Group for Central European History of the American Historical Association, 2011 doi:10.1017/S0008938910001184 Utopian Visions of Family Life in the Stalin-Era Soviet Union Lauren Kaminsky OVIET socialism shared with its utopian socialist predecessors a critique of the conventional family and its household economy.1 Marx and Engels asserted Sthat women’s emancipation would follow the abolition of private property, allowing the family to be a union of individuals within which relations between the sexes would be “a purely private affair.”2 Building on this legacy, Lenin imag- ined a future when unpaid housework and child care would be replaced by com- munal dining rooms, nurseries, kindergartens, and other industries. The issue was so central to the revolutionary program that the Bolsheviks published decrees establishing civil marriage and divorce soon after the October Revolution, in December 1917. These first steps were intended to replace Russia’s family laws with a new legal framework that would encourage more egalitarian sexual and social relations. A complete Code on Marriage, the Family, and Guardianship was ratified by the Central Executive Committee a year later, in October 1918.3 The code established a radical new doctrine based on individual rights and gender equality, but it also preserved marriage registration, alimony, child support, and other transitional provisions thought to be unnecessary after the triumph of socialism. Soviet debates about the relative merits of unfettered sexu- ality and the protection of women and children thus resonated with long-standing tensions in the history of socialism. I would like to thank Atina Grossmann, Carola Sachse, and Mary Nolan, as well as the anonymous reader for Central European History, for their comments and suggestions. -

Babadzhanian, Hamazasp

Babadzhanian, Hamazasp Born: February 18th, 1906 Died: November 1st, 1977 (Aged 71) Ethnicity: Armenian Field of Activity: Red Army Brief Biography Hamazasp Khachaturi Babadzhanian was a Russian military general who served during multiple wars for the Soviet Union, rising to prominence during the Great Patriotic War. He was born in 1906 into an impecunious Armenian family in Chardakhlu, Azerbaijan. He attended a secondary school in Tiflis in 1915 but due to familial financial difficulties was forced to return home and toil in the fields on his family’s plot of land, later working as a highway worker during 1923-24. Babadzhanian joined the Red Army in 1925 and later attended a Military School in Yerevan in 1926, graduating as an officer in 1929, as well as joining the Soviet Communist Party in 1928. He received various postings, mopping up armed gangs in the Caucasus region in 1930 and aided in liquidating the Kulak revolt. Babadzhanian moved around frequently, generally within the Transcaucasus and Baku regions, until 1939-1940, when he served in the Finno-Soviet war. He played a pivotal role in numerous battles in World War 2, participating in the battle of Smolensk, as well as contributing a fundamentally in Yelnya, where he overcame a far superior German force. For his efforts in recapturing Stanslav he received the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. He provided support in Poland, as well fighting in Berlin, contributing to the capture of the Reichstag. After the Great Patriotic War Babadzhanian would prove crucial in quelling the Hungarian Revolution in 1956, and some time after in 1975 became Chief Marshal of the Tank and Armoured Troops, a rank only he and one other attained. -

Friendly Fire Project Examines How a Country Views Itself by How It Tells Its War Story, We Are Also Very Interested in What Other Countries Consume for Entertainment

00:00:00 Music Music Soft, melancholy, somewhat eerie music. 00:00:01 Adam Host If it feels like there are a lot of films about Stalingrad, you’re not Pranica wrong. A quick search in your movie streaming service of choice—or if you’re so lucky, a brick-and-mortar video store—will reveal ten of them. Although only one, to our knowledge, has a scene depicting a Rachel Weisz hand job. It’s enough film content to spin off a podcast of its own, and I’ve already pitched Earwolf a show about German/Russian World War II films with an emphasis on fighter plane aerodynamics/equestrian cavalry enclosures hosted by fifth-year college seniors from acting school with limb fractures called The Stalingrad Stall Stall Stallin’ Grad Cast Cast Cast. For comparison, there are only five more films made about Pearl Harbor, and that’s if you don’t disqualify the Michael Bay movie, which we do. This Stalingrad film is the most successful Russian film of all time, earning 51 million domestically in Russia and $68 million globally. And while the Friendly Fire project examines how a country views itself by how it tells its war story, we are also very interested in what other countries consume for entertainment. Stalingrad accomplishes both. But does that say anything about the importance of this battle in the story of World War II, and the historical record? Well, in our experience watching war films, sometimes quantity doesn’t equal quality. And this is a film that tries very hard to project quality. -

A Life on the Left: Moritz Mebel’S Journey Through the Twentieth Century

Swarthmore College Works History Faculty Works History 4-1-2007 A Life On The Left: Moritz Mebel’s Journey Through The Twentieth Century Robert Weinberg Swarthmore College, [email protected] Marion J. Faber , translator Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-history Part of the German Language and Literature Commons, and the History Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Robert Weinberg and Marion J. Faber , translator. (2007). "A Life On The Left: Moritz Mebel’s Journey Through The Twentieth Century". The Carl Beck Papers In Russian And East European Studies. Issue 1805. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-history/533 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Carl Beck Papers Robert Weinberg, Editor in Russian & Marion Faber, Translator East European Studies Number 1805 A Life on the Left: Moritz Mebel’s Journey Through the Twentieth Century Moritz Mebel and his wife, Sonja The Carl Beck Papers in Russian & East European Studies Number 1805 Robert Weinberg, Editor Marion Faber, Translator A Life on the Left: Moritz Mebel’s Journey Through the Twentieth Century Marion Faber is Scheuer Family Professor of Humanities at Swarthmore College. Her previous translations include Sarah Kirsch’s The Panther Woman (1989) and Friedrich Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil (1998). -

Vodka and Pickled Cabbage: Eastern European Travels of a Professional Economist*

CENTRE FOR ECONOMIC REFORM AND TRANSFORMATION School of Management and Languages, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, EH14 4AS Tel: 0131 451 4202 Fax: 0131 451 3498 email: [email protected] World-Wide Web: http://www.sml.hw.ac.uk/cert (ebook) Vodka and Pickled Cabbage: Eastern European Travels of a Professional Economist* Paul G. Hare‡ September 2008 Discussion Paper 2008/08 Abstract One of the most amazing ‘events’ of the last 15 plus years has been the complete transformation of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, their transition from communist rule and central planning to various forms of market-type economy. Ten of the countries have now joined the EU as full members, and for them this accession marks the real end of the Cold War, the end of the postwar divide between East and West. As a professional economist - initially as a PhD student, eventually as an economics professor based in Scotland - I have worked on the region since the late 1960s, travelling to diverse places in many countries, getting to know the people, observing the economic system both under central planning and as it was transformed to a market system. Finally, in 2006, I decided to write a book about my experiences in the region. The result is not a technical academic work of the sort I normally write. It is a mix of economic history; short accounts of what I do or have done as a professional economist working in an endlessly fascinating part of the world; and travel tale, since my work has taken me to some quite obscure and not at all well known places. -

Penalties and Rewards in Soviet Law

Washington Law Review Volume 25 Number 2 5-1-1950 Penalties and Rewards in Soviet Law George C. Guins Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation George C. Guins, Far Eastern Section, Penalties and Rewards in Soviet Law, 25 Wash. L. Rev. & St. B.J. 206 (1950). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlr/vol25/iss2/6 This Far Eastern Section is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington Law Review by an authorized editor of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FAR EASTERN SECTION PENALTIES AND REWARDS IN SOVIET LAW GEORGE C. GUINS* T HE SOVIET system and practice of penalties and rewards have sev- eral peculiarities which are undoubtedly bound up with Soviet socialism. Long before the Revolution of 1917, the eminent Russian scholar L. J. Petrazicki pointed out that with a transition to socialism there would be greater emphasis on the system of compulsion and rewards.' When the government becomes the supreme monopolist and arbitrator of all earnings and prices, when the livelihood of all its citizens is placed in direct dependence on the state, the stimuli of acquisition, gain, and risk lose their power. The incentive to work is derived from disin- terested devotion to national and humanitarian causes, or from antici- pation of favors from the powers that be. Lofty ideals and altruistic psychological motives are, however, not common among the masses. -

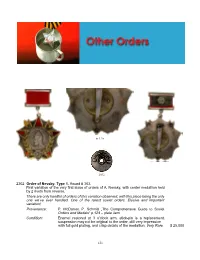

2302 Order of Nevsky. Type 1. Award # 363. First Variation of the Very First Issue of Orders of A. Nevsky, with Center Medallion Held by 2 Rivets from Reverse

to 1.5x 2302 2302 Order of Nevsky. Type 1. Award # 363. First variation of the very first issue of orders of A. Nevsky, with center medallion held by 2 rivets from reverse. There are only handful of orders of this variation observed, with this piece being the only one we’ve ever handled. One of the rarest soviet orders. Elusive and important variation! Provenance: P. McDaniel, P. Schmitt „The Comprehensive Guide to Soviet Orders and Medals“ p.124 – plate item. Condition: Enamel restored at 3 o’clock arm, stick-pin is a replacement, suspension may not be original to the order, still very impressive with full gold plating, and crisp details of the medallion. Very Rare $ 25,000 121 2303 2303 Order of Nevsky. Type 2. Award # 9464. Original silver nut. Comes with copies of official research from Ministry of Defense of Russian Federation – awarded to Guards Captain V. Volosyankin, company commander of 131st Guards Rifle Regiment, 45th Rifle Division, 30th Guards Rifle Corps. English translation attached. Also comes with Certificate of Authenticity from Paul McDaniel (6 out of 10 condition rating). Condition: Light patina, some red enamel replaced, about 50% of the gold-plating remains $ 4,000 2304 2304 Order of Nevsky. Type 3. Award # 12370. Variation 3. Early "ìîíåòíûé äâîð" issue. Original silver nut. Comes with copies of official research from Ministry of Defense of Russian Federation – awarded to Guards Major S. Zinakov, commander of special armor train detachment. English translation attached. Condition: Dark patina with full gold-plating remaining. Superb $ 4,000 2305 122 2305 Complete documented group of Jun. -

WHO's WHO in the WAR in EUROPE the War in Europe 7 CHARLES DE GAULLE

who’s Who in the War in Europe (National Archives and Records Administration, 342-FH-3A-20068.) POLITICAL LEADERS Allies FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT When World War II began, many Americans strongly opposed involvement in foreign conflicts. President Roosevelt maintained official USneutrality but supported measures like the Lend-Lease Act, which provided invaluable aid to countries battling Axis aggression. After Pearl Harbor and Germany’s declaration of war on the United States, Roosevelt rallied the country to fight the Axis powers as part of the Grand Alliance with Great Britain and the Soviet Union. (Image: Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-128765.) WINSTON CHURCHILL In the 1930s, Churchill fiercely opposed Westernappeasement of Nazi Germany. He became prime minister in May 1940 following a German blitzkrieg (lightning war) against Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. He then played a pivotal role in building a global alliance to stop the German juggernaut. One of the greatest orators of the century, Churchill raised the spirits of his countrymen through the war’s darkest days as Germany threatened to invade Great Britain and unleashed a devastating nighttime bombing program on London and other major cities. (Image: Library of Congress, LC-USW33-019093-C.) JOSEPH STALIN Stalin rose through the ranks of the Communist Party to emerge as the absolute ruler of the Soviet Union. In the 1930s, he conducted a reign of terror against his political opponents, including much of the country’s top military leadership. His purge of Red Army generals suspected of being disloyal to him left his country desperately unprepared when Germany invaded in June 1941. -

Enemy at the Gates

IS IT TRUE? 0. IS IT TRUE? - Story Preface 1. STALINGRAD 2. SOVIET RESISTANCE 3. THE SIEGE OF STALINGRAD 4. VASILY ZAITSEV 5. TANIA CHERNOVA 6. STALINGRAD SNIPERS 7. THE DUEL 8. IS IT TRUE? 9. OPERATION URANUS 10. HITLER FORBIDS SURRENDER 11. GERMAN SURRENDER 12. THE SWORD OF STALINGRAD Most scholars recognize Antony Beevor’s 1998 book, Stalingrad: The Fateful Siege, as the best account of the battle. Beevor interviewed survivors and uncovered extraordinary documents in both German and Russian archives. His monumental work discusses Vasily Zaitsev and his talents as a sniper. But of the duel story, Beevor reports, at page 204: Some Soviet sources claim that the Germans brought in the chief of their sniper school to hunt down Zaitsev, but that Zaitsev outwitted him. Zaitsev, after a hunt of several days, apparently spotted his hide under a sheet of corrugated iron, and shot him dead. The telescopic sight off his prey’s rifle, allegedly Zaitsev’s most treasured trophy, is still exhibited in the Moscow armed forces museum, but this dramatic story remains essentially unconvincing. If the telescopic sight is still on display, and the story made all the papers, why does Beevor think it is not convincing? It is worth noting that there is absolutely no mention of it[the duel] in any of the reports to Shcherbakov [chief of the Red Army political department], even though almost every aspect of ‘sniperism’ was reported with relish. What did Vasily Zaitsev have to say about the duel? Living to old age in the Ukraine, where he was the director of an engineering school in Kiev, this Hero of the Soviet Union was apparently quoted by Alan Clark in Barbarossa: The sun rose. -

Orders, Medals and Decorations

Orders, Medals and Decorations To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Lower Grosvenor Gallery The Aeolian Hall, Bloomfield Place New Bond Street London W1A 2AA Day of Sale: Thursday 1 December 2016 at 12.00 noon and 2.30 pm Public viewing: Nash House, St George Street, London W1S 2FQ Monday 28 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Tuesday 29 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Wednesday 30 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Or by previous appointment. Catalogue no. 83 Price £15 Enquiries: Paul Wood, David Kirk or James Morton Cover illustrations: Lot 239 (front); lot 344 (back); lot 35 (inside front); lot 217 (inside back) Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Online Bidding This auction can be viewed online at www.the-saleroom.com, www.numisbids.com and www.sixbid.com. Morton & Eden Ltd offers an online bidding service via www.the-saleroom.com. This is provided on the under- standing that Morton & Eden Ltd shall not be responsible for errors or failures to execute internet bids for reasons including but not limited to: i) a loss of internet connection by either party; ii) a breakdown or other problems with the online bidding software; iii) a breakdown or other problems with your computer, system or internet connec- tion. -

International Research and Exchanges Board Records

International Research and Exchanges Board Records A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Prepared by Karen Linn Femia, Michael McElderry, and Karen Stuart with the assistance of Jeffery Bryson, Brian McGuire, Jewel McPherson, and Chanté Wilson-Flowers Manuscript Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2011 International Research and Exchanges Board Records Page ii Collection Summary Title: International Research and Exchanges Board Records Span Dates: 1947-1991 (bulk 1956-1983) ID No: MSS80702 Creator: International Research and Exchanges Board Creator: Inter-University Committee on Travel Grants Extent: 331,000 items; 331 cartons; 397.2 linear feet Language: Collection material in English and Russian Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: American service organization sponsoring scholarly exchange programs with the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe in the Cold War era. Correspondence, case files, subject files, reports, financial records, printed matter, and other records documenting participants’ personal experiences and research projects as well as the administrative operations, selection process, and collaborative projects of one of America’s principal academic exchange programs. International Research and Exchanges Board Records Page iii Contents Collection Summary .......................................................... ii Administrative Information ......................................................1 Organizational History..........................................................2 -

Russia's Strategic Mobility

Russia’s Strategic Mobility: Supporting ’Hard Pow Supporting ’Hard Mobility: Strategic Russia’s Russia’s Strategic Mobility Supporting ’Hard Power’ to 2020? The following report examines the military reform in Russia. The focus is on Russia’s military-strategic mobility and assess- ing how far progress has been made toward genuinely enhanc- ing the speed with which military units can be deployed in a N.McDermott Roger er’ to2020? theatre of operations and the capability to sustain them. In turn this necessitates examination of Russia’s threat environ- ment, the preliminary outcome of the early reform efforts, and consideration of why the Russian political-military leadership is attaching importance to the issue of strategic mobility. Russia’s Strategic Mobility Supporting ’Hard Power’ to 2020? Roger N. McDermott FOI-R--3587--SE ISSN1650-1942 www.foi.se April 2013 Roger N. McDermott Russia’s Strategic Mobility Supporting ‘Hard Power’ to 2020? Title Russia’s Strategic Mobility: Supporting ‘Hard Power’ to 2020? Titel Rysk strategisk mobilitet: Stöd för maktut- övning till 2020? Report no FOI-R--3587--SE Month April Year 2013 Antal sidor/Pages 101 p ISSN 1650-1942 Kund/Customer Försvarsdepartementet/ Ministry of Defence Projektnr/Project no A11301 Godkänd av/Approved by Maria Lignell Jakobsson Ansvarig avdelning/Departement Försvarsanalys/Defence Analysis This work is protected under the Act on Copyright in Literary and Artistic Works (SFS 1960:729). Any form of reproduction, translation or modification without permission is prohibited. Cover photo: Denis Sinyakov, by permission. www.denissinyakov.com FOI-R--3587--SE Summary Since 2008, Russia’s conventional Armed Forces have been subject to a contro- versial reform and modernization process designed to move these structures be- yond the Soviet-legacy forces towards a modernized military.