An Interactionist Perspective on Centrality and Racial Discrimination in Professional Baseball

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vigilará Profeco Precios a Útiles

Nogales, Sonora, México Buenos días AÑO 17 • NÚMERO 6069 Sonora y Arizona 31 PÁGINAS • 4 SECCIONES HOY ES MIÉRCOLES 14 $10 pesos • Un dólar en Arizona DE AGOSTO DE 2019 AL PONERSE EN MARCHA PARQUE SOLAR “LA OREJANA” Produce Sonora energía limpia Es un gran impulso al desarrollo económico del Estado: Gobernadora Hermosillo, Sonora que dijo, cualquier empresa de ese ru- bro puede invertir en la entidad. os parques fotovoltaicos en “Estoy muy contenta que la se- Sonora son una gran opor- cretaria de Energía, Rocío Nahle, haya tunidad para el desarrollo venido aquí a inaugurar la planta, económico y la implemen- contenta con los inversionistas, pero tación de energías limpias, sobre todo, contenta por los sonoren- aseguró la gobernadora ses porque es una forma de generar LClaudia Pavlovich Arellano, al reunirse beneficios para el estado; vengan a con la secretaria de Energía federal, invertir a Sonora, es una tierra fértil, Rocío Nahle García, luego de ser inau- pueden hacerlo con facilidades, aquí gurado el parque solar La Orejana, con estamos para facilitar toda inver- una inversión de 131 millones de dóla- sión”, aseguró la gobernadora Pavlo- res, por parte de Zuma Energía. vich. La funcionaria federal y el se- Durante el evento, y en repre- cretario de Economía, Jorge Vidal sentación de la gobernadora Claudia Ahumada, inauguraron dicho parque, Pavlovich Arellano, Vidal Ahumada uno de los más grandes en la entidad, subrayó que los esfuerzos del lanza- que tendrá capacidad de generar has- miento de la Estrategia de Crecimien- ta 162 megawatts a través de 500 mil to Verde, por parte de la mandataria paneles ubicados en 338 hectáreas. -

Cincinnati Reds'

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings August 2, 2018 THIS DAY IN REDS HISTORY 1939-The Reds announce plans to add 3,100 seats to Crosley Field, by adding a second deck to the pavilions down the left and right field lines MLB.COM Poor defense, baserunning sink Reds in finale Four-run rally in 7th cut short after Casali thrown out at home plate By Mark Sheldon MLB.com @m_sheldon Aug. 1st, 2018 DETROIT -- Since he became Reds interim manager in April, Jim Riggleman has made attention to detail a big part of his daily message to the players. At times throughout the season, Riggleman has organized drills that focus on fundamentals from baserunning, to cutoff throws, covering bases and more. So it wasn't hard to see the disappointment Riggleman felt following a 7-4 Reds loss to the Tigers that completed Detroit's two- game series sweep. Numerous mistakes befuddled Cincinnati defensively and on the bases at Comerica Park. "When you play like that, you're not supposed to win," Riggleman said. "It's not bad effort, it's bad performance. We just have to somehow find a way to clean it up. It was very sloppy." Some of the mistakes included: • Left fielder Phillip Ervin twice missed the cutoff man on hits and it cost the Reds two runs. • A relay throw from shortstop Jose Peraza one-hopped over catcher Curt Casali's head for another run. • Casali ran into a double play during a four-run rally in the seventh inning. "That's the difference between a good club and a really good club," Casali said. -

F(Error) = Amusement

Academic Forum 33 (2015–16) March, Eleanor. “An Approach to Poetry: “Hombre pequeñito” by Alfonsina Storni”. Connections 3 (2009): 51-55. Moon, Chung-Hee. Trans. by Seong-Kon Kim and Alec Gordon. Woman on the Terrace. Buffalo, New York: White Pine Press, 2007. Peraza-Rugeley, Margarita. “The Art of Seen and Being Seen: the poems of Moon Chung- Hee”. Academic Forum 32 (2014-15): 36-43. Serrano Barquín, Carolina, et al. “Eros, Thánatos y Psique: una complicidad triática”. Ciencia ergo sum 17-3 (2010-2011): 327-332. Teitler, Nathalie. “Rethinking the Female Body: Alfonsina Storni and the Modernista Tradition”. Bulletin of Spanish Studies: Hispanic Studies and Researches on Spain, Portugal and Latin America 79, (2002): 172—192. Biographical Sketch Dr. Margarita Peraza-Rugeley is an Assistant Professor of Spanish in the Department of English, Foreign Languages and Philosophy at Henderson State University. Her scholarly interests center on colonial Latin-American literature from New Spain, specifically the 17th century. Using the case of the Spanish colonies, she explores the birth of national identities in hybrid cultures. Another scholarly interest is the genre of Latin American colonialist narratives by modern-day female authors who situate their plots in the colonial period. In 2013, she published Llámenme «el mexicano»: Los almanaques y otras obras de Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (Peter Lang,). She also has published short stories. During the summer of 2013, she spent time in Seoul’s National University and, in summer 2014, in Kyungpook National University, both in South Korea. https://www.facebook.com/StringPoet/ The Best Players in New York Mets History Fred Worth, Ph.D. -

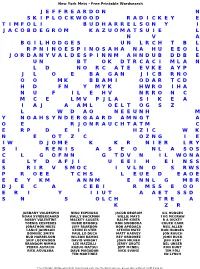

Jeffreardonnskiplockw

New York Mets - Free Printable Wordsearch JEFFREARDON N SKIPLOCKWOOD RADICKEYE TIMFOLI BUDHARRELSONY I JACOBDEGROMKAZ UOMATSUIE L NV A BGILHODGES UNLRCHTBL RPNINOESPINOSAHAN AHUEEOL JORDANYVALDESPINNM AHNDUBDDBE UNBT OKDTRCACIMLA N LDNORC ATEEVKEAYP JLOE BAGANJICB RNO OOMK BBAMIODART CD HDFNY MYKHWROI HA NUFIL EHVNRRO NC MCELMV PJLASIK EA IAJAAML OELTOGSZ LWD AONEEUNH M YNOAHSYNDERGAARD AMNGT A OE RJONRAUCHTATM C ERPDE I HZICWK NEOT ZC OZNGIE IWDJOME KKRNI ERLRY SIRENI SASEO NLASOS CLGOFNN GTDVNIL WONA ELYDAFJ IUEEI HEINSS SRIRVSMO CIVLN OSRWS PROEE TCHSLEU EDEAOE EEYKM ANNMENNL GMBR DJECA CEBIRMS SEOO ERIY IIUTAAE TSSD SN SOLCH TREA KZ R JORDANY VALDESPIN NINO ESPINOSA JACOB DEGROM GIL HODGES NOAH SYNDERGAARD WALLY BACKMAN WILLIE MAYS TUG MCGRAW BOBBY VALENTINE MACKEY SASSER RALPH KINER R A DICKEY YOENIS CESPEDES HUBIE BROOKS RON SWOBODA CHUCK CARR JONATHON NIESE JEFF REARDON BOB APODACA NEIL ALLEN LANCE JOHNSON KEVIN ELSTER STEVEN MATZ RON HODGES DOMINIC SMITH PAUL LO DUCA MATT HARVEY JON RAUCH BUD HARRELSON WILSON RAMOS REY ORDONEZ JOHN BUCK SKIP LOCKWOOD DAVID WRIGHT JOHN MILNER JEFF KENT BRANDOM NIMMO LEE MAZZILLI JERRY GROTE DEL UNSER PEDRO ASTACIO KAZUO MATSUI JEFF MCNEIL RON HUNT RICK AGUILERA DAVE MAGADAN NICK EVANS TIM FOLI TED MARTINEZ ED LYNCH Free Printable Wordsearch from LogicLovely.com. Use freely for any use, please give a link or credit if you do. New York Mets - Free Printable Wordsearch JDUFFYDYERJA YBRUCEEDHEARN ORM ARCUSSTROMAN HIMIKEJACOBS TTACARLOSDELGAD OK IOANKRMOVAU GHNE MMSSSRMG JUSTINWILSON TMDTDAREAE KT EIREONAENO -

Cubs 2013 Preview: a Bit Better Pitching, but Rebuilding Still Grinds Along Slowly

Cubs 2013 preview: A bit better pitching, but rebuilding still grinds along slowly By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Friday, March 29, 2013 Theo Epstein is getting double for his money these days. First, the former lifelong Bostonian is getting a valuable education in Chicago politics as the three- cornered debate over Wrigley Field renovations shows how Clout City USA really works. And yet all the arguments over whether the Cubs should get seri- ous with Rosemont and consider moving if they don’t get a renova- Cubs GM Jed Hoyer (with wife Merrill) and boss Theo Ep- tions deal very soon give Epstein stein have once again constructed a roster that can be and his baseball operations depart- disassembled via mid-season trades. ment a big break. Off-the-field issues involving Wrigley Field, whether the installation of lights, falling concrete or Arne Harris’ hat shots, are always far more than sideshows. They become the main story, relegating the Cubs’ on-field fortunes to notebook status. The taffy pull involving Tom Ricketts, Rahm Emanuel, Tom Tunney, the rooftop owners and the vil- lage of Rosemont absolutely shifted the Cubs’ spring-training countdown to Opening Day to secondary news-angle status. If all focus was on the team itself, the conclusion would be a sub-standard roster with a slew of place-holders that is being intentionally fielded for the second-year in a row. Worse yet, as Epstein vows a rebuilding-from-the-ground-up strategy, there are no pitching phenoms or fresh-faced hot rookies as attention-getters to make the continual losing more palatable. -

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

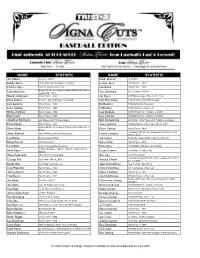

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank -

Former Hostage to Speak at ND by SEAN S

ACCENT: Holy Cross Associates in Chile Balmy Mostly sunny, high in the mid VIEWPOINT: Don’t overlook poverty 70s. JEJ T h e O b s e r v e r ___________________ VOL . XXI, NO. 43 MONDAY, NOVEMBER 2, 1987 the independent newspaper serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary's Former hostage to speak at ND By SEAN S. HICKEY Damascus, Syria, in Nov. 1984. Staff Reporter “They met with Syrian offi cials, Palestinian ■‘groups and A former Beirut hostage will almost anyone they could find, be speaking tonight at Galvin including representatives of Life Science at 8 in room 283. Syrian prime-minister Assad,” A Beirut bureau chief for the said Gaffney. He added it is un Cable News Network and pres clear whether Levin escaped ently a Woodrow Wilson Fellow because of his own ingenuity or at Princeton University, Jerry his wife’s efforts. Levin was abducted by the Is “The mystery is whether he lamic Jihad on March 7, 1984 escaped or was released in while walking to work in directly,” said Gaffney. “Most Beirut. The militant Shi’ite observers feel that it was spe group held him prisoner for 343 cial that he got away as op days until February 1985. posed to a disguised release. “Notre Dame had a secret Anyway it is clear that Lucille connection in Levin’s escape,” Levin met her husband’s cap said Father Patrick Gaffney, tors.” an assistant professor and a Islamic Jihad, a radical Middle East specialist. Shi’ite Muslim group issued a That connection was statement the week after they Landrum Bolling, director of released Levin saying they the Notre Dame Institute of decided to do so because they Ecumenical Studies in Israel, determined he was not a sub who was contacted by Levin’s versive. -

Justin Morneau Elected to Minnesota Twins Hall of Fame Morneau Will Become the 34Th Member of the Twins Hall of Fame

TICKETS SCHEDULE SCORES STATS News Twins Press Releases Justin Morneau elected to Minnesota Twins Hall Of Fame Morneau will become the 34th member of the Twins Hall of Fame January 24, 2020 MINNEAPOLIS-ST. PAUL, MN — The Minnesota Twins announced today that former Twins first baseman Justin Morneau has been elected to the club’s Hall of Fame. Morneau will become the 34th member of the Twins Hall of Fame when he is inducted during an on-field pre-game ceremony at Target Field before the Twins host the Chicago White Sox on Saturday, May 23 in a game presented by Sheboygan Sausage Company. The Twins Hall of Fame, which honors players, managers, coaches and off-field personnel who have contributed to the organization’s growth and success since Minnesota broke into the major leagues in 1961, was created as part of the club’s 40th Season Celebration in 2000. The inaugural class of Twins Hall of Famers—Harmon Killebrew, Rod Carew, Tony Oliva, Kent Hrbek, Kirby Puckett and Calvin Griffith — was inducted on August 12, 2000. Other inductees include: pitcher Jim Kaat and broadcaster Herb Carneal (2001); pitcher Bert Blyleven and manager Tom Kelly (2002); long-time public address announcer Bob Casey and outfielder Bob Allison (2003); catcher Earl Battey (2004); pitcher Frank Viola (2005) and owner Carl Pohlad (2005); shortstop Zoilo Versalles (2006); third baseman Gary Gaetti (2007) and farm director Jim Rantz (2007); pitcher Rick Aguilera (2008); pitcher Brad Radke and farm and scouting director George Brophy (2009); shortstop Greg Gagne (2010); pitcher Jim Perry (2011); pitcher Camilo Pascual (2012); pitcher Eddie Guardado and director of media relations Tom Mee (2013); second baseman Chuck Knoblauch was elected in 2014 but not inducted; outfielder Torii Hunter and radio broadcaster John Gordon (2016); outfielder Michael Cuddyer and former general manager Andy MacPhail (2017); pitcher Johan Santana (2018); and, pitcher Joe Nathan and former club president Jerry Bell (2019). -

My Replay Baseball Encyclopedia Fifth Edition- May 2014

My Replay Baseball Encyclopedia Fifth Edition- May 2014 A complete record of my full-season Replays of the 1908, 1952, 1956, 1960, 1966, 1967, 1975, and 1978 Major League seasons as well as the 1923 Negro National League season. This encyclopedia includes the following sections: • A list of no-hitters • A season-by season recap in the format of the Neft and Cohen Sports Encyclopedia- Baseball • Top ten single season performances in batting and pitching categories • Career top ten performances in batting and pitching categories • Complete career records for all batters • Complete career records for all pitchers Table of Contents Page 3 Introduction 4 No-hitter List 5 Neft and Cohen Sports Encyclopedia Baseball style season recaps 91 Single season record batting and pitching top tens 93 Career batting and pitching top tens 95 Batter Register 277 Pitcher Register Introduction My baseball board gaming history is a fairly typical one. I lusted after the various sports games advertised in the magazines until my mom finally relented and bought Strat-O-Matic Football for me in 1972. I got SOM’s baseball game a year later and I was hooked. I would get the new card set each year and attempt to play the in-progress season by moving the traded players around and turning ‘nameless player cards” into that year’s key rookies. I switched to APBA in the late ‘70’s because they started releasing some complete old season sets and the idea of playing with those really caught my fancy. Between then and the mid-nineties, I collected a lot of card sets. -

Sox's New Trier Connection Gets Stronger with Tilson, Huff

White Sox's New Trier High connection gets stronger with Charlie Tilson, Mike Huff By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Thursday, March 9, 2017 The White Sox’s historical New Trier High School connection just got a little stronger. His status as the team’s center fielder coming out of camp de- layed due to a stress reaction in his right foot, Wilmette native Charlie Tilson has made friends with a fellow alum of the legendary north suburban school, traditionally rated as Charlie Tilson (left) already has been in contact with fellow one of the best academically in New Trier alum Mike Huff (right), working at a Bulls/Sox Acad- the country. emy clinic with ex-slugger Jim Thome. Former Sox outfielder Mike Huff, vice president of baseball/fastpitch, and bunting and baserunning instructor at the west suburban Lisle-based BullsSox Academy, was New Trier’s representative on the 1993 AL West champion Sox. Since Tilson came into the Sox organization last summer via a trade from the Cardinals, the fellow former Trevians have had “a couple of great conversations.” Then they stayed in touch via e-mail. “Stay true to yourself,” was Huff’s main counsel to Tilson, slowed in Glendale due to a foot injury. If Tilson does win the center-field job, and needs some familiar pick-me-up from Huff, the latter will consider asking the permission of GM Rick Hahn and manager Ricky Renteria for supplement the advice the kid gets from Sox coaches. “I know they’d be 100 percent behind that,” said Huff. -

Sunflower December 12, 1977

Foreign languagee Monday remain In demand December 12,1977 By MIKE SHIELDS LXXXII No. 49 Wichita State University has not shared in the resurgence of Wlchlte State University interest in foreign language study that is taking place on many American campuses, according to Eugene Savaiano, chairperson of the WSU Department of Romance Languages. The reason there has been no resurgence in interest, Savaiano believes, is because there was never a decline in interest in foreign languages at WSU. population in this region of the “We have, in the period that country has contributed to main many universities experienced a tained interest in foreign language decline in foreign languages, held here, Savaiano said. our own, and in some semesters He also credits the federal have even had an increase in government's interest in foreign foreign language enrollment,** Sa language education as a factor in vaiano said. orfbAer The large Hispanic-American * turn to page 5 Troubl9$ In CHRP Resignations spark controversy By KATE McLEMORE Rodenberg said all of the faculty The meeting ended when Roden position which would be at a lower Staff Writer members' resignations, except for berg said he was open to questions salary." Tension mounted last Friday as respiratory therapy (RT) King's, was of their own volition. but would not engage in a debate. Barlow said he knew that legally Rodenberg had to honor King's students of the College of Health Related Professions (CHRP) “King's resignation was promp In an interview, Barlow, an RT ted by me because of a loss of instructor, agreed with King and verbal contract with him since gathered for a 9 a.m. -

Eatontown Stores Test Blue Law

The Daily Register VOL.99 NO 127 SHREWSBURY, N. J. TUESDAY, DECEMBER 7, 1976 15 CENTS Eatontown stores may test blue law By JULIE MCDONNELL and Middlesex prohibit the stores In the mall would alto sary we will make purchases sale of clothing, furniture, follow the lead of the large on that Sunday to be vtcd as EATONTOWN - Bamber- and several other categories stores and stay open. evidence. If tbe stores open " ger's is "seriously con- of Items on Sunday. Paul Morton, executive di- Eatontown Police Ch*f WU templating" opening Its Mon Robert Austin, a spokesman rector of the Red Bank Area Ham Zadorotny said Ms de- mouth Mall store here on the for Hahne'i in Newark, said Chamber of Commerce, said partment "hasn't had a Sunday before Christmas, in his store "would probably fol- he would immediately protest chance to assess tie situ- defiance of the county's blue low suit" and open Its Mon the mall's opening ation" yet. laws. mouth MaU store on Dec II If "We will ask the Eatontown "But 1 would say we will Paul Kastner, public rela- Bamberger'i Is open police and the county prose- probably Issue summonses tions spokesman for the shop- And Mr Kastner predicted cutor to see that the law Is agalntt any stores that open ping center, said yesterday that most of the smaller enforced," he Mid "If neces- Illegally," he said afternoon that he had re- Thousands of shoppers look ceived word that Bamber- advantage of the Sunday ger's would be open Sunday, openings in shopping centers Dec.