Japanese Character Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Study of Old Documents of Hokkaido and Kuril Ainu

NINJAL International Symposium 2018 Approaches to Endangered Languages in Japan and Northeast Asia, August 6-8 The study of old documents of Hokkaido and Kuril Ainu: Promise and Challenges Tomomi Sato (Hokkaido U) & Anna Bugaeva (TUS/NINJAL) [email protected] [email protected]) Introduction: Ainu • AINU (isolate, North Japan, moribund) • Is the only non-Japonic lang. of Japan. • Major dialect groups : Hokkaido (moribund), Sakhalin (extinct since 1993), Kuril (extinct since the end of XIX). • Was also spoken in Tōhoku till mid XVIII. • Hokkaido Ainu dialects: Southwestern (well documented) Northeastern (less documented) • Is not used in daily conversation since the 1950s. • Ethnical Ainu: 100,000. 2 Fig. 2 Major language families in Northeast Asia (excluding Sinitic) Amuric Mongolic Tungusic Ainuic Koreanic Japonic • Ainu shares only few features with Northeast Asian languages. • Ainu is typologically “more like a morphologically reduced version of a North American language.” (Johanna Nichols p.c.). • This is due to the strongly head-marking character of Ainu (Bugaeva, to appear). Why is it important to study Ainu? • Ainu culture is widely regarded as a direct descendant of the Jōmon culture which was spread in the Japanese archipelago in the Prehistoric time from about 14,000 BC. • Ainu is the only surviving Jōmon language; there had been other Jōmon lgs too: about 300 lgs (Janhunen 2002), cf. 10 lgs (Whitman, p.c.) . • Ainu is likely to be much more typical of what languages were like in Northeast Asia several millennia ago than the picture we would get from Chinese, Japanese or Korean. • Focusing on Ainu can help us understand a period of northeast Asian history when political, cultural and linguistic units were very different to what they have been since the rise of the great historically-attested states of East Asia. -

Introduction to Kanbun: W4019x (Fall 2004) Mondays and Wednesdays 11-12:15, Kress Room, Starr Library (Entrance on 200 Level)

1 Introduction to Kanbun: W4019x (Fall 2004) Mondays and Wednesdays 11-12:15, Kress Room, Starr Library (entrance on 200 Level) David Lurie (212-854-5034, [email protected]) Office Hours: Tuesdays 2-4, 500A Kent Hall This class is intended to build proficiency in reading the variety of classical Japanese written styles subsumed under the broad term kanbun []. More specifically, it aims to foster familiarity with kundoku [], a collection of techniques for reading and writing classical Japanese in texts largely or entirely composed of Chinese characters. Because it is impossible to achieve fluent reading ability using these techniques in a mere semester, this class is intended as an introduction. Students will gain familiarity with a toolbox of reading strategies as they are exposed to a variety of premodern written styles and genres, laying groundwork for more thorough competency in specific areas relevant to their research. This is not a class in Classical Chinese: those who desire facility with Chinese classical texts are urged to study Classical Chinese itself. (On the other hand, some prior familiarity with Classical Chinese will make much of this class easier). The pre-requisite for this class is Introduction to Classical Japanese (W4007); because our focus is the use of Classical Japanese as a tool to understand character-based texts, it is assumed that students will already have control of basic Classical Japanese grammar. Students with concerns about their competence should discuss them with me immediately. Goals of the course: 1) Acquire basic familiarity with kundoku techniques of reading, with a focus on the classes of special characters (unread characters, twice-read characters, negations, etc.) that form the bulk of traditional Japanese kanbun pedagogy. -

Problematika České Transkripce Japonštiny a Pravidla Jejího Užívání Nihongo 日本語 社会 Šakai Fudži 富士 Ivona Barešová, Monika Dytrtová Momidži Tókjó もみ じ 東京 Čotto ち ょっ と

チェ コ語 翼 čekogo cubasa šin’jó 信用 Problematika české transkripce japonštiny a pravidla jejího užívání nihongo 日本語 社会 šakai Fudži 富士 Ivona Barešová, Monika Dytrtová momidži Tókjó もみ じ 東京 čotto ち ょっ と PROBLEMATIKA ČESKÉ TRANSKRIPCE JAPONŠTINY A PRAVIDLA JEJÍHO UŽÍVÁNÍ Ivona Barešová Monika Dytrtová Spolupracovala: Bc. Mária Ševčíková Oponenti: prof. Zdeňka Švarcová, Dr. Mgr. Jiří Matela, M.A. Tento výzkum byl umožněn díky účelové podpoře na specifi cký vysokoškolský výzkum udělené roku 2013 Univerzitě Palackého v Olomouci Ministerstvem školství, mládeže a tělovýchovy ČR (FF_2013_044). Neoprávněné užití tohoto díla je porušením autorských práv a může zakládat občanskoprávní, správněprávní, popř. trestněprávní odpovědnost. 1. vydání © Ivona Barešová, Monika Dytrtová, 2014 © Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci, 2014 ISBN 978-80-244-4017-0 Ediční poznámka V publikaci je pro přepis japonských slov užito české transkripce, s výjimkou jejich výskytu v anglic kém textu, kde se objevuje původní transkripce anglická. Japonská jména jsou uváděna v pořadí jméno – příjmení, s výjimkou jejich uvedení v bibliogra- fi ckých citacích, kde se jejich pořadí řídí citační normou. Pokud není uvedeno jinak, autorkami překladů citací a parafrází jsou autorky této práce. V textu jsou použity následující grafi cké prostředky. Fonologický zápis je uveden standardně v šikmých závorkách // a fonetický v hranatých []. Fonetické symboly dle IPA jsou použity v rámci kapi toly 5. V případě, že není nutné zaznamenávat jemné zvukové nuance dané hlásky nebo že není kladen důraz na zvukové rozdíly mezi jed- notlivými hláskami, je jinde v textu, kde je to možné, z důvodu usnadnění porozumění užito namísto těchto specifi ckých fonetických symbolů písmen české abecedy, např. -

A Functional MRI Study on the Japanese Orthographies

Modulation of the Visual Word Retrieval System in Writing: A Functional MRI Study on the Japanese Orthographies Kimihiro Nakamura1, Manabu Honda2, Shigeru Hirano1, Tatsuhide Oga1, Nobukatsu Sawamoto1, Takashi Hanakawa1, Downloaded from http://mitprc.silverchair.com/jocn/article-pdf/14/1/104/1757408/089892902317205366.pdf by guest on 18 May 2021 Hiroshi Inoue3, Jin Ito3, Tetsu Matsuda1, Hidenao Fukuyama1, and Hiroshi Shibasaki1 Abstract & We used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to left sensorimotor areas and right cerebellum. The kanji versus examine whether the act of writing involves different neuro- kana comparison showed increased responses in the left psychological mechanisms between the two script systems of prefrontal and anterior cingulate areas. Especially, the lPITC the Japanese language: kanji (ideogram) and kana (phono- showed a significant task-by-script interaction. Two additional gram). The main experiments employed a 2 Â 2 factorial control tasks, repetition (REP) and semantic judgment (SJ), design that comprised writing-to-dictation and visual mental activated the bilateral perisylvian areas, but enhanced the lPITC recall for kanji and kana. For both scripts, the actual writing response only weakly. These results suggest that writing of the produced a widespread fronto-parietal activation in the left ideographic and phonographic scripts, although using the hemisphere. Especially, writing of kanji activated the left largely same cortical regions, each modulates the visual word- posteroinferior temporal cortex (lPITC), whereas that of retrieval system according to their graphic features. Further- kana also yielded a trend of activation in the same area. more, comparisons with two additional tasks indicate that the Mental recall for both scripts activated similarly the left parieto- activity of the lPITC increases especially in expressive language temporal regions including the lPITC. -

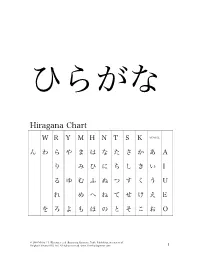

Hiragana Chart

ひらがな Hiragana Chart W R Y M H N T S K VOWEL ん わ ら や ま は な た さ か あ A り み ひ に ち し き い I る ゆ む ふ ぬ つ す く う U れ め へ ね て せ け え E を ろ よ も ほ の と そ こ お O © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 1 Beginning Japanese 名前: ________________________ 1-1 Hiragana Activity Book 日付: ___月 ___日 一、 Practice: あいうえお かきくけこ がぎぐげご O E U I A お え う い あ あ お え う い あ お う あ え い あ お え う い お う い あ お え あ KO KE KU KI KA こ け く き か か こ け く き か こ け く く き か か こ き き か こ こ け か け く く き き こ け か © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 2 GO GE GU GI GA ご げ ぐ ぎ が が ご げ ぐ ぎ が ご ご げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ が が ご げ ぎ が ご ご げ が げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ ご げ が 二、 Fill in each blank with the correct HIRAGANA. SE N SE I KI A RA NA MA E 1. -

Handy Katakana Workbook.Pdf

First Edition HANDY KATAKANA WORKBOOK An Introduction to Japanese Writing: KANA THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT FOR BEGINNING LEVEL JAPANESE LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION. \ FrF!' '---~---- , - Y. M. Shimazu, Ed.D. -----~---- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENlS vii STUDYSHEET#l 1 A,I,U,E, 0, KA,I<I, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #1 2 PRACTICE: A, I,U, E, 0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU, GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #2 3 MORE PRACTICE: A, I, U, E,0, KA,KI,KU, KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #~3 4 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: A,I,U, E,0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N STUDYSHEET #2 5 SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI,ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #4 6 PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, 'lSU,TE,TO, OA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #5 7 MORE PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE,SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE, W, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORKSHEET #6 8 ADDmONAL PRACI'ICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI,TSU,TE,TO, DA, DE,DO STUDYSHEET #3 9 NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE, HO, BA, BI,BU,BE,BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #7 10 PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE,HO, BA,BI, BU,BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #8 11 MORE PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA,HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,BU,BE, BO, PA,PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #9 12 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,3U, BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO STUDYSHEET #4 13 MA, MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET#10 14 PRACTICE: MA,MI, MU,ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #11 15 MORE PRACTICE: MA, MI,MU,ME,MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #12 16 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: MA,MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO STUDYSHEET #5 17 -

A Student Model of Katakana Reading Proficiency for a Japanese Language Intelligent Tutoring System

A Student Model of Katakana Reading Proficiency for a Japanese Language Intelligent Tutoring System Anthony A. Maciejewski Yun-Sun Kang School of Electrical Engineering Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana 47907 Abstract--Thls work describes the development of a kanji. Due to the limited number of kana, their relatively low student model that Is used In a Japanese language visual complexity, and their systematic arrangement they do Intelligent tutoring system to assess a pupil's not represent a significant barrier to the student of Japanese. proficiency at reading one of the distinct In fact, the relatively small effort required to learn katakana orthographies of Japanese, known as k a t a k a n a , yields significant returns to readers of technical Japanese due to While the effort required to memorize the relatively the high incidence of terms derived from English and few k a t a k a n a symbols and their associated transliterated into katakana. pronunciations Is not prohibitive, a major difficulty In reading katakana Is associated with the phonetic This work describes the development of a system that is modifications which occur when English words used to automatically acquire knowledge about how English which are transliterated Into katakana are made to words are transliterated into katakana and then to use that conform to the more restrictive rules of Japanese information in developing a model of a student's proficiency in phonology. The algorithm described here Is able to reading katakana. This model is used to guide the instruction automatically acquire a knowledge base of these of the student using an intelligent tutoring system developed phonological transformation rules, use them to previously [6,8]. -

Chinese Script Generation Panel Document

Chinese Script Generation Panel Document Proposal for the Generation Panel for the Chinese Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone 1. General Information Chinese script is the logograms used in the writing of Chinese and some other Asian languages. They are called Hanzi in Chinese, Kanji in Japanese and Hanja in Korean. Since the Hanzi unification in the Qin dynasty (221-207 B.C.), the most important change in the Chinese Hanzi occurred in the middle of the 20th century when more than two thousand Simplified characters were introduced as official forms in Mainland China. As a result, the Chinese language has two writing systems: Simplified Chinese (SC) and Traditional Chinese (TC). Both systems are expressed using different subsets under the Unicode definition of the same Han script. The two writing systems use SC and TC respectively while sharing a large common “unchanged” Hanzi subset that occupies around 60% in contemporary use. The common “unchanged” Hanzi subset enables a simplified Chinese user to understand texts written in traditional Chinese with little difficulty and vice versa. The Hanzi in SC and TC have the same meaning and the same pronunciation and are typical variants. The Japanese kanji were adopted for recording the Japanese language from the 5th century AD. Chinese words borrowed into Japanese could be written with Chinese characters, while Japanese words could be written using the character for a Chinese word of similar meaning. Finally, in Japanese, all three scripts (kanji, and the hiragana and katakana syllabaries) are used as main scripts. The Chinese script spread to Korea together with Buddhism from the 2nd century BC to the 5th century AD. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Simplification of Chinese Characters in Japan and China

CONTRASTING APPROACHES TO CHINESE CHARACTER REFORM: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIMPLIFICATION OF CHINESE CHARACTERS IN JAPAN AND CHINA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIAN STUDIES AUGUST 2012 By Kei Imafuku Thesis Committee: Alexander Vovin, Chairperson Robert Huey Dina Rudolph Yoshimi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express deep gratitude to Alexander Vovin, Robert Huey, and Dina R. Yoshimi for their Japanese and Chinese expertise and kind encouragement throughout the writing of this thesis. Their guidance, as well as the support of the Center for Japanese Studies, School of Pacific and Asian Studies, and the East-West Center, has been invaluable. i ABSTRACT Due to the complexity and number of Chinese characters used in Chinese and Japanese, some characters were the target of simplification reforms. However, Japanese and Chinese simplifications frequently differed, resulting in the existence of multiple forms of the same character being used in different places. This study investigates the differences between the Japanese and Chinese simplifications and the effects of the simplification techniques implemented by each side. The more conservative Japanese simplifications were achieved by instating simpler historical character variants while the more radical Chinese simplifications were achieved primarily through the use of whole cursive script forms and phonetic simplification techniques. These techniques, however, have been criticized for their detrimental effects on character recognition, semantic and phonetic clarity, and consistency – issues less present with the Japanese approach. By comparing the Japanese and Chinese simplification techniques, this study seeks to determine the characteristics of more effective, less controversial Chinese character simplifications. -

KANA Response Live Organization Administration Tool Guide

This is the most recent version of this document provided by KANA Software, Inc. to Genesys, for the version of the KANA software products licensed for use with the Genesys eServices (Multimedia) products. Click here to access this document. KANA Response Live Organization Administration KANA Response Live Version 10 R2 February 2008 KANA Response Live Organization Administration All contents of this documentation are the property of KANA Software, Inc. (“KANA”) (and if relevant its third party licensors) and protected by United States and international copyright laws. All Rights Reserved. © 2008 KANA Software, Inc. Terms of Use: This software and documentation are provided solely pursuant to the terms of a license agreement between the user and KANA (the “Agreement”) and any use in violation of, or not pursuant to any such Agreement shall be deemed copyright infringement and a violation of KANA's rights in the software and documentation and the user consents to KANA's obtaining of injunctive relief precluding any further such use. KANA assumes no responsibility for any damage that may occur either directly or indirectly, or any consequential damages that may result from the use of this documentation or any KANA software product except as expressly provided in the Agreement, any use hereunder is on an as-is basis, without warranty of any kind, including without limitation the warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, and non-infringement. Use, duplication, or disclosure by licensee of any materials provided by KANA is subject to restrictions as set forth in the Agreement. Information contained in this document is subject to change without notice and does not represent a commitment on the part of KANA. -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role. -

Legacy Character Sets & Encodings

Legacy & Not-So-Legacy Character Sets & Encodings Ken Lunde CJKV Type Development Adobe Systems Incorporated bc ftp://ftp.oreilly.com/pub/examples/nutshell/cjkv/unicode/iuc15-tb1-slides.pdf Tutorial Overview dc • What is a character set? What is an encoding? • How are character sets and encodings different? • Legacy character sets. • Non-legacy character sets. • Legacy encodings. • How does Unicode fit it? • Code conversion issues. • Disclaimer: The focus of this tutorial is primarily on Asian (CJKV) issues, which tend to be complex from a character set and encoding standpoint. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations dc • GB (China) — Stands for “Guo Biao” (国标 guóbiâo ). — Short for “Guojia Biaozhun” (国家标准 guójiâ biâozhün). — Means “National Standard.” • GB/T (China) — “T” stands for “Tui” (推 tuî ). — Short for “Tuijian” (推荐 tuîjiàn ). — “T” means “Recommended.” • CNS (Taiwan) — 中國國家標準 ( zhôngguó guójiâ biâozhün) in Chinese. — Abbreviation for “Chinese National Standard.” 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations (Cont’d) dc • GCCS (Hong Kong) — Abbreviation for “Government Chinese Character Set.” • JIS (Japan) — 日本工業規格 ( nihon kôgyô kikaku) in Japanese. — Abbreviation for “Japanese Industrial Standard.” — 〄 • KS (Korea) — 한국 공업 규격 (韓國工業規格 hangug gongeob gyugyeog) in Korean. — Abbreviation for “Korean Standard.” — ㉿ — Designation change from “C” to “X” on August 20, 1997. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations (Cont’d) dc • TCVN (Vietnam) — Tiu Chun Vit Nam in Vietnamese. — Means “Vietnamese Standard.” • CJKV — Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated What Is A Character Set? dc • A collection of characters that are intended to be used together to create meaningful text.