Warrenbayne Boho Ground Water

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Benalla Rural Women's Health Needs Project Report 2019

RURAL WOMEN’S HEALTH NEEDS PROJECT BENALLA LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA (JULY-OCTOBER 2019) FUNDED BY MURRAY PRIMARY HEALTH NETWORK (PHN) Contents 1 Title Page: Rural Women’s Health Needs Project – Benalla Local Government Area ..................... 3 2 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 4 3 Background ..................................................................................................................................... 7 4 Summary of activity ....................................................................................................................... 11 5 Findings ........................................................................................................................................ 18 5.1 Rural Women’s Health Needs ................................................................................................... 18 5.2 Service Needs Analysis ............................................................................................................. 32 5.3 Proposed Service Model .......................................................................................................... 33 6 Recommendations ........................................................................................................................ 34 7 Achievements, challenges and key learnings ................................................................................ 35 8 References .................................................................................................................................. -

List of Parishes in the State of Victoria

List of Parishes in the State of Victoria Showing the County, the Land District, and the Municipality in which each is situated. (extracted from Township and Parish Guide, Department of Crown Lands and Survey, 1955) Parish County Land District Municipality (Shire Unless Otherwise Stated) Acheron Anglesey Alexandra Alexandra Addington Talbot Ballaarat Ballaarat Adjie Benambra Beechworth Upper Murray Adzar Villiers Hamilton Mount Rouse Aire Polwarth Geelong Otway Albacutya Karkarooc; Mallee Dimboola Weeah Alberton East Buln Buln Melbourne Alberton Alberton West Buln Buln Melbourne Alberton Alexandra Anglesey Alexandra Alexandra Allambee East Buln Buln Melbourne Korumburra, Narracan, Woorayl Amherst Talbot St. Arnaud Talbot, Tullaroop Amphitheatre Gladstone; Ararat Lexton Kara Kara; Ripon Anakie Grant Geelong Corio Angahook Polwarth Geelong Corio Angora Dargo Omeo Omeo Annuello Karkarooc Mallee Swan Hill Annya Normanby Hamilton Portland Arapiles Lowan Horsham (P.M.) Arapiles Ararat Borung; Ararat Ararat (City); Ararat, Stawell Ripon Arcadia Moira Benalla Euroa, Goulburn, Shepparton Archdale Gladstone St. Arnaud Bet Bet Ardno Follett Hamilton Glenelg Ardonachie Normanby Hamilton Minhamite Areegra Borug Horsham (P.M.) Warracknabeal Argyle Grenville Ballaarat Grenville, Ripon Ascot Ripon; Ballaarat Ballaarat Talbot Ashens Borung Horsham Dunmunkle Audley Normanby Hamilton Dundas, Portland Avenel Anglesey; Seymour Goulburn, Seymour Delatite; Moira Avoca Gladstone; St. Arnaud Avoca Kara Kara Awonga Lowan Horsham Kowree Axedale Bendigo; Bendigo -

Database of Reported Locations

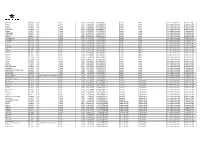

Baddaginnie VIC-0054 N/A Victoria 3670 -36.58903233 145.8610841 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Benalla VIC-0133 N/A Victoria 3672 -36.55087549 145.9843655 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Boweya VIC-0217 N/A Victoria 3675 -36.27044072 146.1305207 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Boxwood VIC-0220 N/A Victoria 3725 -36.32247489 145.799552 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Broken Creek VIC-0238 N/A Victoria 3673 -36.42950203 145.8878857 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Bungeet VIC-0278 N/A Victoria 3726 -36.29082618 146.0508309 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Bungeet West VIC-0279 N/A Victoria 3726 -36.35586874 146.0115074 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Chesney Vale VIC-0377 N/A Victoria 3725 -36.41750116 146.0460414 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Devenish VIC-0509 N/A Victoria 3726 -36.33413827 145.8935252 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Glenrowan West VIC-0719 N/A Victoria 3675 -36.52061494 146.151517 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Goomalibee VIC-0729 N/A Victoria 3673 -36.46568 145.859318 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Goorambat VIC-0734 N/A Victoria 3725 -36.41800712 145.9275169 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Lima VIC-1056 N/A Victoria 3673 -36.7382385 145.9563763 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia -

The Landcare Revolving Loan Fund a Development Report

The Landcare Revolving Loan Fund A Development Report A report for the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation by Derek Mortimer Broken Catchment Landcare Network March 2003 RIRDC Publication No 03/025 RIRDC Project No BCL-1A © 2003 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 0642 58593 8 ISSN 1440-6845 The Landcare Revolving Loan Fund - A Development Report Publication No. 03/025 Project No.BCL-1A. The views expressed and the conclusions reached in this publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of persons consulted. RIRDC shall not be responsible in any way whatsoever to any person who relies in whole or in part on the contents of this report. This publication is copyright. However, RIRDC encourages wide dissemination of its research, providing the Corporation is clearly acknowledged. For any other enquiries concerning reproduction, contact the Publications Manager on phone 02 6272 3186. Researcher Contact Details Mr Derek Mortimer C/- PO Box 124 Benalla, VIC 3672 Phone:(03) 57 611 516 Fax:(03) 57611 628 Email: C/- [email protected] In submitting this report the report, the researcher has agreed to RIRDC publishing this material in its edited form. RIRDC Contact Details Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation Level 1, AMA House 42 Macquarie Street BARTON ACT 2600 PO Box 4776 KINGSTON ACT 2604 Phone: 02 6272 4539 Fax: 02 6272 5877 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.rirdc.gov.au Published in March 2003 Printed on environmentally friendly paper by Canprint i Foreword A revolving loan fund can be described as a capital fund from which loans are made, usually for projects of public benefit. -

Historical Earthquakes in Victoria: a Revised List Kevin Mccue Australian Seismological Centre, Canberra, ACT 2601

Historical earthquakes in Victoria: A Revised List Kevin McCue Australian Seismological Centre, Canberra, ACT 2601 Abstract This paper lists felt-earthquakes in Victoria before 1954 with better-substantiated dates, magnitudes and locations. A significant earthquake and aftershock listed in 1868 actually occurred in 1869. Earthquakes felt throughout Melbourne in 1862 and 1892 and others have been re- discovered; surprising how often earthquakes have rattled Melbourne and suburbs. This and other new information has been mainly sourced from old Australian newspapers using TROVE the Australian National Library’s on-line scans of early newspapers and other sources. A plot of the historical data shows a similar distribution but not frequency of epicentres to the post-1965 data which will lower uncertainties in hazard assessments by improving source zone definitions, activity rates and the magnitude threshold of completeness intervals. The events described include poorly studied, moderate-sized earthquakes that shook Melbourne in 1885, 1922 and Benalla in 1946, let alone the two destructive Warrnambool earthquakes in 1903, each with one small felt aftershock. More damage was caused by these moderate earthquakes than is generally acknowledged. VICTORIAN SEISMICITY Various authors wrote about earthquakes in Victoria before short-period seismographs were introduced; Griffiths (1885), Baracchi (numerous newspaper reports), Gregory (1903), Burke- Gaffney (1951) who provided the first list upgraded by Underwood (1972) and Doyle and others (1968). Gibson and others (1980) extracted the larger events in Underwood’s list and assigned them magnitudes (for M≥4) based on their felt areas and maximum intensity. No large (M≥ 6) earthquakes have occurred in Victoria (or NSW) since European settlement in the early 1800s but geographers such as Hills (1963), Bowler and Harford (1966) and Twidale and Stehbens (1978) identified Recent fault scarps in the state left by large earthquakes in prehistoric times, some of which have subsequently been dated (McPherson and others, 2012). -

A History of Violet Town and St Dunstan's Church by Rev. George Edwards

Preface Researched and written by Reverend George W. Edwards of the Anglican Church of St Dunstan about 1984. No attempt has been made to edit the text in this document, only to put it in a new format, with sketches scanned in as images and photographs placed where appropriate. Scattered through the document are notes by the author explaining something, sometimes preceded by G.W.E., the initials of the author. All first-person comments are those of the author An History of Violet Town Introduction My interest in St. Dunstan's history grew out of reading Mwley Crocker's (and friends) "A Short History (of) Saint Dunstan's Church, Violet Town. In its brevity it left all sorts of questions unanswered; and his own remark that it ought to be enlarged and added to encouraged me to investigations of my own. If in what follows I refer to his work only to seemingly show up its errors - not so; it is only because it was this book that I started my inquiries from. In any case, it seems only fair to explain why I differ from what he gathered in good faith and what has been read by many. He begins by setting the life of St Dunstan's in the context of the township of Violet Town and its origins; and I follow him in that, beginning with what might be called Violet Town's pre-history. 1, "PRE-HISTORY:" (a) begins with the aborigines of the area; but at this stage I know nothing about them except for the attack on the Faithfull stock convoy as it passed through (now) Benalla on its way south. -

Goulburn Lower

o! y w H l l e R w iverina H e wy N Joint Fuel Management YEILIMA - TULLAH Top End RA CREEK +$ Top Island RA Program FFMVIC GOULBURN BARMAH NP - Cobram STEAMERS PLAIN (Lower) Strathmerton Black Swamp 2020-2021 TO 2022-2023 Barmah Lake # y # # w H b b o C # # # # # # # BURRAMINE - # y DUFFYS LANE w # # H - SLASHING y # e l l # # +$ Picola a V Katunga y M a u r r r ra u y +$ V 2020-21 Planned Burn (<50Ha) M a ll ey H Barmah w Wahgunyah # y Yarrawonga # # # # +$ # # # # # 2021-22 Planned Burn (<50Ha) Bundalong # # # # # # +$ 2022-23 Planned Burn (<50Ha) Waaia E # Nathalia Lake +$ # # Moodemere 2020-21 Planned Burn (50Ha +) # # # Katamatite NUMURKAH - 2021-22 Planned Burn (50Ha +) o! y NUMURKAH NCR w +$ H +$ y KATAMATITE - e l TUNGAMAH - l a KATAMATITE 2022-23 Planned Burn (50Ha +) M V BBSP - HILL u rr n BUSHLAND RESERVE ay r PLAIN RD V u b all l ey u H o w G y Non Burning Treatment - Mineral Earth Disturbance E DRUMANURE KANYAPELLA - KANYAPELL#A - # WYUNA - - BBSP - KANYAPELLA KANYAPELLA # YYNAC-YAMBUNA-BLACK GORDONS RD # WETLANDS Echuca WETLANDS # GATE LGNP # # # # Non Burning Treatment - Vegetation Modification +$ +$ +$ # # +$ # # KANYAPELLA - WYUNA - YYNAC-WYUNA KANYAPELLA - YOUANMITE - KANYAPELLA +$ 97-LGNP WYUNA - KANYAPELLA WYUNA - +$ YYNAC-WYUNA YOUANMITE NATURE PEECHELBA - WETLANDS +$ Wunghnu # Railway Line E WETLANDS YYNAC-MILLERS CONSERVATION RESERVE PEECHELBA ROAD +$ TRACK-LGNP # # BEND-LGNP WYUNA - +$ STRATEGIC BREAK YYNAC-EMILY Tungamah +$ JANE LGNP TUNGAMAH - Freeway # # THREE CHAIN # # RD (CFA) # # +$ Highway +$ Peechelba Wyuna -

Milestones Memories Messages&

M ilestones M emories & M essages Milestones Memories A H Messages& isto ry of Landca re in the Go ulburn Broken Catchment Broken ulburn A History of Landcare in the Goulburn Broken Catchment Print Production: Billongaloo Print Management ISBN 978-1-920742-14-0 MILESTONES, MEMORIES & MESSAGES: A History of Landcare In The Goulburn Broken Catchment Prepared for the Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority by Carole Hamilton Barwick ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Images supplied by: Ancona Landcare Group, Delatite Landcare Group, Merton Landcare This project began with a proposal by Katie Brown, Regional Landcare Group, Molesworth Landcare Group, Waranga Landcare Group, Coordinator for the Goulburn Broken Catchment, to capture the history Warrenbayne Boho Land Protection Group, Strathbogie Tablelands of the distinct energies and diverse geographies of the 90 Landcare Landcare Group, Sunday Creek Dry Creek Landcare Group, Sheep Pen Groups, Local Area Plan and other environmental groups involved in Creek Land Protection Group, Goulburn Murray Landcare Network, important projects in land protection and natural resource management, Poppe Davis, Tallarook Landcare Group, Dabyminga Landcare Group, as a fitting way to mark twenty years of Landcare. Hughes Creek Catchment Collaborative, Goulburn Broken CMA library, I wish to acknowledge the following people who contributed to the History of Tooborac Group: Nulla Vale Pyalong West Landcare Group. formulation and completion of the project: The many Landcare Groups and members who contributed their enthusiasm, -

Conservation Plan

Conservation Plan for the Strathbogie Landscape Zone Biodiversity Action Planning in the Mid Goulburn 1 Developed By: Environmental Management Program, Sustainable Irrigated Landscapes, Department of Primary Industries, for the Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority. Developed under the guidance of the Biodiversity Action Planning Steering Committee - comprising personnel from the Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority, Department of Primary Industries, Department of Sustainability and Environment and Trust for Nature (Vic). Rowhan Marshall 89 Sydney Rd Benalla, Victoria 34052 Phone: (03) 57611 611 Fax: (03) 57611 628 Acknowledgments: This project is funded as part of the Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority Regional Catchment Strategy in the Mid Goulburn Region and is provided with support and funding from the Australian and Victorian Governments. This project is delivered primarily through partnerships between the Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority, Department of Primary Industries, Department of Sustainability and Environment, Trust for Nature (Vic) and other community bodies. Personnel from these agencies provided generous support and advice during the development of this plan. We also thank numerous Landholders, Landcare groups, Local Area Planning Groups and other individuals, who also provided generous support, advice; information and assistance wherever possible (refer to acknowledgment section). Front cover: Lima East Valley Inset: Feathertail Glider Photos: Rowhan Marshall, Len Robinson -

The De-Amalgamation of Delatite Shire

“They’re Not Like Us” – The De-amalgamation of Delatite Shire 'They're Not Like Us' – The De-amalgamation of Delatite Shire Dr Peter Cheni Centre for Public Policy Department of Political Science Faculty of Arts University of Melbourne +61 3 8344 3505 [email protected] Abstract The compulsory amalgamation of Victorian local governments under the Kennett government in the mid 1990s led to a major period of upheaval and reform across the entire sector. Forced into 'mega councils' with appointed administrators and cuts to rate income, all councils struggled to merge political and administrative systems and cultures, manage service delivery, and move to new public management principles of contract management and privatisation of council functions. While most municipalities grudgingly accepted the new centrally-determined boundaries, Delatite Shire in North-East Victoria saw ongoing resistance to the amalgamation from its southern community of Mansfield, bitterly opposed to the amalgamation with Benalla and the perceived loss of services and government staff from their region. From the formation of a locally-based residents' association, the first democratically-elected council of the new Shire was largely replaced by one comprised of pro-de- amalgamation representatives, who successfully lobbied the State government for the opportunity to present a case for splitting the Shire. Following ongoing community consultation, the Council has been given the opportunity to split, an administrative exercise that will increase rates and create a new Shire dependent on contracted services from surrounding municipalities. Examining the case, this paper explores the public debate and political strategies employed to advance and realise the de- amalgamation policy, examining the problems associated with forming a community of interest within the new Shire. -

Annual Report 2017-18

GOULBURN BROKEN CATCHMENT MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY GOULBURN BROKEN CATCHMENT ANNUAL REPORT 2017-18 GOULBURN BROKEN CATCHMENT MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY ANNUAL REPORT 2017-18 RATINGS LEGEND Well below target Below target On target Exceeded target 2017-18 performance (less than 50%) (50 to 80%) (80 to 110%) (more than 110%) Catchment condition and Critical attribute contribution Very poor Poor Satisfactory Good to excellent to resilience Risk to Trend 2015-18 Increasing significantly Increasing Stable Declining system resilience Long-term Very high High Medium Low Long-term strategy Watch and Escalated Early Middle Late implementation stage maintain response The Goulburn Broken CMA continues to develop its approach to catchment condition and performance reporting using a resilience model aligned to the Goulburn Broken Regional Catchment Strategy 2013-2019. Appendix 1 (page 128) discusses why and how ratings are applied. Although annual performance indicators have high certainty relative to long-term indicators, the uncertainty in setting and monitoring annual targets is still significant because of irregular timing of projects and project-delivery adaptation throughout the financial year. This uncertainty is reflected in an assessment of delivering ‘on target’ being defined as a large range. ABOUT THIS REPORT This report provides information on the Goulburn Broken © State of Victoria. Goulburn Broken Catchment Catchment Management Authority’s (CMA) performance and Management Authority 2018. This publication is finances, which can be assessed against its 2017-18 to 2021-22 copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process Corporate Plan targets. except in accordance with provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. The Goulburn Broken Catchment’s resilience is explicitly assessed to inform an adaptive approach, consistent with the Goulburn Broken ISSN 978-1-876600-02-0 Regional Catchment Strategy 2013-2019. -

Nov05 (2) (Read-Only)

is produced monthly by the editorial board of the Violet Town Action Group. November 2005 Postage Paid “Priceless” No. 287 Coordinator: Terry Frewin ph. 5790 8635 Sunday 30 October Iris Show Please Note that opinions expressed in arti- Monday 31 “ Landcare day cles & letters etc. in the Village Voice are not 2 VTAG meets necessarily those of the editorial board & 6 Seed Savers meet VTAG. 7 Probus meets Articles to be in the box at Delahey's Super- 11 RSL Armistice Day service market by the 20th of each month, or may be 12 Market Day & historic train posted to R.M.B. 3061, Violet Town 3669, OR 12 Goulburn Valley History Day emailed to Terry at [email protected]. 13 Garden Ideas, Sunnyside 16 Fitness Centre meeting Interested in local & If the 20th falls on a Sunday, then there will be environmental history? a final pick up from the boxes on the following 18 Paddock trees, Warrenbayne From a family that has been in the Monday. 20 C’wealth Games warm up day The University of Melbourne’s Professor Janet McCal- Goulburn Valley a long time? 21 Garden Club meets 24 VTBNC Ladies Auxiliary meet man, Ass. Professor Don Garden & PhD students will be Own a farm that was a selection or 28 70’s+ Christmas luncheon visiting the region on Violet Town Market Day & they want a soldier settler’s block? to hear from you! They are developing a history of the Have rainfall records that date back Business Advertisement Rates Goulburn Valley as a man-made rural environment & a long time? need the input of local community members.