The De-Amalgamation of Delatite Shire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intro Managed Locations Legend

A r t w o r k z L o c a t i o n s INTRO LEGEND MANAGED LOCATIONS LOCAL TOURISM RESOURCES GET UP GET OUT GET EXPLORING LOCATIONS eBOOK Freely produced by Artworkz volunteers Special thanks to Allan Layton, James Cowell and Kathie Maynes All GPS coordinates found in this eBook are provided as points of reference for computer mapping only and must never be relied upon for travel. All downloads, links, maps, photographs, illustrations and all information contained therein are provided in draft form and are produced by amateurs. It relies on community input for improvement. Many locations in this eBook are dangerous to visit and should only be visited after talking with the relevant governing body and gaining independent gps data from a reliable source. Always ensure you have the appropriate level of skill for getting to each location and that you are dressed appropriately. Always avoid being in the bush during days of high fire danger, always let someone know of your travel plans and be aware of snakes and spiders at all times. You can search this eBook using your pdf search feature Last updated: 24 November 2020 Artworkz, serving our community e B O O K INTRODUCTION There is often some confusion in the local tourism industry as to who manages what assets and where those assets are located. As there appears to be no comprehensive and free public listing of all local tourism features, we are attempting to build one with this eBook. Please recognise that errors and omissions will occur and always cross reference any information found herein with other more established resources, before travelling. -

Property and User Charges at Alpine Resorts and Victorian Municipalities

Property and User Charges at Alpine Resorts and Victorian Municipalities August 2008 Published by the Alpine Resorts Co-ordinating Council, July 2008. An electronic copy of this document is also available on www.arcc.vic.gov.au. Reprinted with corrections, August 2008 © The State of Victoria, Alpine Resorts Co-ordinating Council 2008. This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. This report was commissioned by the Alpine Resorts Co-ordinating Council. It was prepared by Saturn Corporate Resources Pty Ltd. Authorised by Victorian Government, Melbourne. Printed by Typo Corporate Services, 97-101 Tope Street, South Melbourne 100% Recycled Paper ISBN 978-1-74208-341-4 (print) ISBN 978-1-74208-342-1 (PDF) Front Cover: Sunrise over Mount Buller Village. Acknowledgements: Photo Credit: Copyright Mount Buller / Photo: Nathan Richter. Disclaimer: This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and the Alpine Resorts Co-ordinating Council do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. The views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Victorian Government or the Alpine Resorts Co-ordinating Council. Property and User Charges at Alpine Resorts and Victorian Municipalities A Comparison of Occupier -

Mansfield Shire Council Annual Report 2018-19

MANSFIELD SHIRE MANSFIELD SHIRE COUNCIL - ANNUAL REPORT 2018-19 2 MANSFIELD SHIRE COUNCIL - ANNUAL REPORT 2018-19 Table of Contents Introduction 5 Welcome to the 2018-19 Annual Report 5 Who Are We? 6 Quick Stats 8 The Year in Review 9 Mayor’s Message 14 Financial Summary 16 Major Capital Works 18 Community Festivals and Events 21 Awards and Recognition 22 Our Council 24 Shire Profile 24 Councillors 24 Our People 27 Executive Management Team 29 Organisational Structure 31 Our Workplace 32 Our Staff 34 Health and Safety 36 Our Performance 37 Planning and Accountability 38 Council Plan 39 Performance 39 Strategic direction 1—Participation and Partnerships 40 Strategic direction 2—Financial Sustainability 43 Strategic direction 3—Community Resilience and Connectivity 47 Strategic direction 4—Enhance Liveability 51 Strategic direction 5—Responsible Leadership 55 Local Government Performance Reporting Framework 58 Governance 66 Governance, Management and Other Information 67 Governance and Management Checklist 74 Statutory Information 77 Financial Report 80 Mansfield Shire Council Financial Report 2018-19 81 Independent Auditor’s Report (Financial) 87 Mansfield Shire Council Performance Statement 2018-19 138 Independent Auditor’s Report (Performance) 155 3 MANSFIELD SHIRE COUNCIL - ANNUAL REORT 2018-19 MANSFIELD SHIRE COUNCIL - ANNUAL REPORT 2018-19 4 MANSFIELD SHIRE COUNCIL - ANNUAL REPORT 2018-19 Introduction Welcome Welcome to Mansfield Shire Council’s Annual Report for 2018-19. Mansfield Shire Council is committed to transparent reporting and accountability to the community and the Annual Report 2018-19 is the primary means of advising the Mansfield community about Council’s operations and performance during the financial year. -

Town and Country Planning Board of Victoria

1965-66 VICTORIA TWENTIETH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING BOARD OF VICTORIA FOR THE PERIOD lsr JULY, 1964, TO 30rH JUNE, 1965 PRESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 5 (2) OF THE TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1961 [Appro:timate Cost of Report-Preparation, not given. Printing (225 copies), $736.00 By Authority A. C. BROOKS. GOVERNMENT PRINTER. MELBOURNE. No. 31.-[25 cents]-11377 /65. INDEX PAGE The Board s Regulations s Planning Schemes Examined by the Board 6 Hazelwood Joint Planning Scheme 7 City of Ringwood Planning Scheme 7 City of Maryborough Planning Scheme .. 8 Borough of Port Fairy Planning Scheme 8 Shire of Corio Planning Scheme-Lara Township Nos. 1 and 2 8 Shire of Sherbrooke Planning Scheme-Shire of Knox Planning Scheme 9 Eildon Reservoir .. 10 Eildon Reservoir Planning Scheme (Shire of Alexandra) 10 Eildon Reservoir Planning Scheme (Shire of Mansfield) 10 Eildon Sub-regional Planning Scheme, Extension A, 1963 11 Eppalock Planning Scheme 11 French Island Planning Scheme 12 Lake Bellfield Planning Scheme 13 Lake Buffalo Planning Scheme 13 Lake Glenmaggie Planning Scheme 14 Latrobe Valley Sub-regional Planning Scheme 1949, Extension A, 1964 15 Phillip Island Planning Scheme 15 Tower Hill Planning Scheme 16 Waratah Bay Planning Scheme 16 Planning Control for Victoria's Coastline 16 Lake Tyers to Cape Howe Coastal Planning Scheme 17 South-Western Coastal Planning Scheme (Shire of Portland) 18 South-Western Coastal Planning Scheme (Shire of Belfast) 18 South-Western Coastal Planning Scheme (Shire of Warrnambool) 18 South-Western Coastal Planning Scheme (Shire of Heytesbury) 18 South-Western Coastal Planning Scheme (Shire of Otway) 18 Wonthaggi Coastal Planning Scheme (Borough of Wonthaggi) 18 Melbourne Metropolitan Planning Scheme 19 Melbourne's Boulevards 20 Planning Control Around Victoria's Reservoirs 21 Uniform Building Regulations 21 INDEX-continued. -

Benalla Rural Women's Health Needs Project Report 2019

RURAL WOMEN’S HEALTH NEEDS PROJECT BENALLA LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA (JULY-OCTOBER 2019) FUNDED BY MURRAY PRIMARY HEALTH NETWORK (PHN) Contents 1 Title Page: Rural Women’s Health Needs Project – Benalla Local Government Area ..................... 3 2 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 4 3 Background ..................................................................................................................................... 7 4 Summary of activity ....................................................................................................................... 11 5 Findings ........................................................................................................................................ 18 5.1 Rural Women’s Health Needs ................................................................................................... 18 5.2 Service Needs Analysis ............................................................................................................. 32 5.3 Proposed Service Model .......................................................................................................... 33 6 Recommendations ........................................................................................................................ 34 7 Achievements, challenges and key learnings ................................................................................ 35 8 References .................................................................................................................................. -

Electronic Gaming Machines Strategy 2015-2020

Electronic Gaming Machines Strategy 2015-2020 Version: 1.1 Date approved: 22 December 2015 Reviewed: 15 January 2019 Responsible Department: Planning Related policies: Nil 1 Purpose ................................................................................................................. 3 2 Definitions ............................................................................................................. 3 3 Acronyms .............................................................................................................. 5 4 Scope .................................................................................................................... 5 5 Executive Summary ............................................................................................. 5 6 Gambling and EGMs in the City of Casey ........................................................... 6 7 City of Casey Position on Electronic Gaming Machines ................................... 7 7.1 Advocacy & Partnerships ....................................................................................... 7 7.2 Local Economy ....................................................................................................... 8 7.3 Consultation & Information Provision ...................................................................... 9 7.4 Community Wellbeing ............................................................................................ 9 7.5 Planning Assessment .......................................................................................... -

Community Engagement Advisory Committees in the Goulburn Broken

Community Engagement Advisory Groups in the Goulburn Broken Catchment An overview Reviewed November 2011 1 | P a g e “Healthy, resilient and increasingly productive landscapes supporting vibrant communities” www.gbcma.vic.gov.au Vision Healthy, resilient and increasingly productive landscapes supporting vibrant communities Purpose Through its leadership and partnerships the Goulburn Broken CMA will improve the resilience of the Catchment’s people, land, biodiversity and water resources in a rapidly changing environment. Goulburn Broken CMA’s Values and Behaviours Environmental Sustainability - we will passionately contribute to improving the environmental health of our catchment. Safety - we vigorously protect and look out for the safety and wellbeing of ourselves, our colleagues and our workers. Partnerships – we focus on teamwork and collaboration across our organisation to develop strategic alliances with partners and the regional community. Leadership – we have the courage to lead change and accept the responsibility to inspire and deliver positive change. Respect – we embrace diversity and treat everyone with fairness, respect, openness and honesty. Achievement, Excellence and Accountability – we do what we say we will do, we do it well and we take responsibility and accountability for our actions. Continuous learning, innovation and improvement – we are an evidence and science-based organisation and we test and challenge the status quo. We learn from our successes and failures and we are continually adapting using internal and external feedback from stakeholders and the environment. We are an agile, flexible and responsive organisation. 2 | P a g e “Healthy, resilient and increasingly productive landscapes supporting vibrant communities” www.gbcma.vic.gov.au At A Glance What: The Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority (CMA) was established as one of 10 CMAs in 1997 under the Catchment and Land Protection Act (CaLP Act) and covering the State of Victoria. -

List of Parishes in the State of Victoria

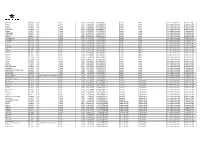

List of Parishes in the State of Victoria Showing the County, the Land District, and the Municipality in which each is situated. (extracted from Township and Parish Guide, Department of Crown Lands and Survey, 1955) Parish County Land District Municipality (Shire Unless Otherwise Stated) Acheron Anglesey Alexandra Alexandra Addington Talbot Ballaarat Ballaarat Adjie Benambra Beechworth Upper Murray Adzar Villiers Hamilton Mount Rouse Aire Polwarth Geelong Otway Albacutya Karkarooc; Mallee Dimboola Weeah Alberton East Buln Buln Melbourne Alberton Alberton West Buln Buln Melbourne Alberton Alexandra Anglesey Alexandra Alexandra Allambee East Buln Buln Melbourne Korumburra, Narracan, Woorayl Amherst Talbot St. Arnaud Talbot, Tullaroop Amphitheatre Gladstone; Ararat Lexton Kara Kara; Ripon Anakie Grant Geelong Corio Angahook Polwarth Geelong Corio Angora Dargo Omeo Omeo Annuello Karkarooc Mallee Swan Hill Annya Normanby Hamilton Portland Arapiles Lowan Horsham (P.M.) Arapiles Ararat Borung; Ararat Ararat (City); Ararat, Stawell Ripon Arcadia Moira Benalla Euroa, Goulburn, Shepparton Archdale Gladstone St. Arnaud Bet Bet Ardno Follett Hamilton Glenelg Ardonachie Normanby Hamilton Minhamite Areegra Borug Horsham (P.M.) Warracknabeal Argyle Grenville Ballaarat Grenville, Ripon Ascot Ripon; Ballaarat Ballaarat Talbot Ashens Borung Horsham Dunmunkle Audley Normanby Hamilton Dundas, Portland Avenel Anglesey; Seymour Goulburn, Seymour Delatite; Moira Avoca Gladstone; St. Arnaud Avoca Kara Kara Awonga Lowan Horsham Kowree Axedale Bendigo; Bendigo -

Australia's Gambling Industries 3 Consumption of Gambling

Australia’s Gambling Inquiry Report Industries Volume 3: Appendices Report No. 10 26 November 1999 Contents of Volume 3 Appendices A Participation and public consultation B Participation in gambling: data tables C Estimating consumer surplus D The sensitivity of the demand for gambling to price changes E Gambling in indigenous communities F National Gambling Survey G Survey of Clients of Counselling Agencies H Problem gambling and crime I Regional data analysis J Measuring costs K Recent US estimates of the costs of problem gambling L Survey of Counselling Services M Gambling taxes N Gaming machines: some international comparisons O Displacement of illegal gambling? P Spending by problem gamblers Q Who are the problem gamblers? R Bankruptcy and gambling S State and territory gambling data T Divorce and separations U How gaming machines work V Use of the SOGS in Australian gambling surveys References III Contents of other volumes Volume 1 Terms of reference Key findings Summary of the report Part A Introduction 1 The inquiry Part B The gambling industries 2 An overview of Australia's gambling industries 3 Consumption of gambling Part C Impacts 4 Impacts of gambling: a framework for assessment 5 Assessing the benefits 6 What is problem gambling? 7 The impacts of problem gambling 8 The link between accessibility and problems 9 Quantifying the costs of problem gambling 10 Broader community impacts 11 Gauging the net impacts Volume 2 Part D The policy environment 12 Gambling policy: overview and assessment framework 13 Regulatory arrangements for major forms of gambling 14 Are constraints on competition justified? 15 Regulating access 16 Consumer protection 17 Help for people affected by problem gambling 18 Policy for new technologies 19 The taxation of gambling 20 Earmarking 21 Mutuality 22 Regulatory processes and institutions 23 Information issues IV V A Participation and public consultation The Commission received the terms of reference for this inquiry on 26 August 1998. -

Database of Reported Locations

Baddaginnie VIC-0054 N/A Victoria 3670 -36.58903233 145.8610841 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Benalla VIC-0133 N/A Victoria 3672 -36.55087549 145.9843655 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Boweya VIC-0217 N/A Victoria 3675 -36.27044072 146.1305207 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Boxwood VIC-0220 N/A Victoria 3725 -36.32247489 145.799552 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Broken Creek VIC-0238 N/A Victoria 3673 -36.42950203 145.8878857 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Bungeet VIC-0278 N/A Victoria 3726 -36.29082618 146.0508309 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Bungeet West VIC-0279 N/A Victoria 3726 -36.35586874 146.0115074 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Chesney Vale VIC-0377 N/A Victoria 3725 -36.41750116 146.0460414 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Devenish VIC-0509 N/A Victoria 3726 -36.33413827 145.8935252 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Glenrowan West VIC-0719 N/A Victoria 3675 -36.52061494 146.151517 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Goomalibee VIC-0729 N/A Victoria 3673 -36.46568 145.859318 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Goorambat VIC-0734 N/A Victoria 3725 -36.41800712 145.9275169 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia 25 February 2016 Lima VIC-1056 N/A Victoria 3673 -36.7382385 145.9563763 Indi Benalla Hume Inner Regional Australia -

Survey of Post-War Built Heritage in Victoria

SURVEY OF POST-WAR BUILT HERITAGE IN VICTORIA STAGE TWO: Assessment of Community & Administrative Facilities Funeral Parlours, Kindergartens, Exhibition Building, Masonic Centre, Municipal Libraries and Council Offices prepared for HERITAGE VICTORIA 31 May 2010 P O B o x 8 0 1 9 C r o y d o n 3 1 3 6 w w w . b u i l t h e r i t a g e . c o m . a u p h o n e 9 0 1 8 9 3 1 1 group CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Project Background 7 1.2 Project Methodology 8 1.3 Study Team 10 1.4 Acknowledgements 10 2.0 HISTORICAL & ARCHITECTURAL CONTEXTS 2.1 Funeral Parlours 11 2.2 Kindergartens 15 2.3 Municipal Libraries 19 2.4 Council Offices 22 3.0 INDIVIDUAL CITATIONS 001 Cemetery & Burial Sites 008 Morgue/Mortuary 27 002 Community Facilities 010 Childcare Facility 35 015 Exhibition Building 55 021 Masonic Hall 59 026 Library 63 769 Hall – Club/Social 83 008 Administration 164 Council Chambers 85 APPENDIX Biographical Data on Architects & Firms 131 S U R V E Y O F P O S T - W A R B U I L T H E R I T A G E I N V I C T O R I A : S T A G E T W O 3 4 S U R V E Y O F P O S T - W A R B U I L T H E R I T A G E I N V I C T O R I A : S T A G E T W O group EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The purpose of this survey was to consider 27 places previously identified in the Survey of Post-War Built Heritage in Victoria, completed by Heritage Alliance in 2008, and to undertake further research, fieldwork and assessment to establish which of these places were worthy of inclusion on the Victorian Heritage Register. -

Victoria Government Gazette No

Victoria Government Gazette No. S 126 Friday 5 May 2006 By Authority. Victorian Government Printer ROAD SAFETY (VEHICLES) REGULATIONS 1999 Class 2 Notice – Conditional Exemption of Heavier and Longer B-doubles with Road Friendly Suspension from Certain Mass Limits 1. Purpose To exempt certain class 2 vehicles from certain mass and dimension limits subject to complying with certain conditions. 2. Authorising provision This Notice is made under regulation 510 of the Road Safety (Vehicles) Regulations 1999. 3. Commencement This Notice comes into operation on the date of its publication in the Government Gazette. 4. Revocation The Notices published in Government Gazette No. S134 of 17 June 2004 and Government Gazette No. S236 of 25 November 2005 are revoked. 5. Expiration This Notice expires on 1 March 2011. 6. Definitions In this Notice – “Regulations” means the Road Safety (Vehicles) Regulations 1999. “road friendly suspension” has the same meaning as in the Interstate Road Transport Regulations 1986 of the Commonwealth. “Approval Plate” means a decal, label or plate issued by a Competent Entity that is made of a material and fixed in such a way that they cannot be removed without being damaged or destroyed and that contains at least the following information: (a) Manufacturer or Trade name or mark of the Front Underrun Protection Vehicle, or Front Underrun Protection Device, or prime mover in the case of cabin strength, or protrusion as appropriate; (b) In the case of a Front Underrun Protection Device or protrusion, the make of the vehicle or vehicles and the model or models of vehicle the component or device has been designed and certified to fit; (c) Competent Entity unique identification number; (d) In the case of a Front Underrun Protection Device or protrusion, the Approval Number issued by the Competent Entity; and (e) Purpose of the approval, e.g.