Organizational Efforts to Prevent Harmful Online Communication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Germany, International Justice and the 20Th Century

Paul Betts Dept .of History University of Sussex NOT TO BE QUOTED WITHOUT PERMISSION OF THE AUTHOR: DRAFT VERSION: THE FINAL DRAFT OF THIS ESSAY WILL APPEAR IN A SPECIAL ISSUE OF HISTORY AND MEMORY IN APRIL, 2005, ED. ALON CONFINO Germany, International Justice and the 20th Century The turning of the millennium has predictably spurred fresh interest in reinterpreting the 20th century as a whole. Recent years have witnessed a bountiful crop of academic surveys, mass market picture books and television programs devoted to recalling the deeds and misdeeds of the last one hundred years. It then comes as no surprise that Germany often figures prominently in these new accounts. If nothing else, its responsibility for World War I, World War II and the Holocaust assures its villainous presence in most every retrospective on offer. That Germany alone experienced all of the modern forms of government in one compressed century – from constitutional monarchy, democratic socialism, fascism, Western liberalism to Soviet-style communism -- has also made it a favorite object lesson about the so-called Age of Extremes. Moreover, the enduring international influence of Weimar culture, feminism and the women’s movement, social democracy, post-1945 economic recovery, West German liberalism, environmental politics and most recently pacifism have also occasioned serious reconsideration of the contemporary relevance of the 20th century German past. Little wonder that several commentators have gone so far as to christen the “short twentieth century” between 1914 and 1989 as really the “German century,” to the extent that German history is commonly held as emblematic of Europe’s 20th century more generally.1 Acknowledging Germany’s central role in 20th century life has hardly made things easy for historians, however. -

The German Netzdg As Role Model Or Cautionary Tale? Implications for the Debate on Social Media Liability

Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 31 XXXI Number 4 Article 4 2021 The German NetzDG as Role Model or Cautionary Tale? Implications for the Debate on Social Media Liability Patrick Zurth Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (LMU), [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj Part of the International Law Commons, and the Internet Law Commons Recommended Citation Patrick Zurth, The German NetzDG as Role Model or Cautionary Tale? Implications for the Debate on Social Media Liability, 31 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 1084 (2021). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol31/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The German NetzDG as Role Model or Cautionary Tale? Implications for the Debate on Social Media Liability Cover Page Footnote Dr. iur., LL.M. (Stanford). Postdoctoral Fellow at the Chair for Private Law and Intellectual Property Law with Information- and IT-Law (GRUR-chair) (Prof. Dr. Matthias Leistner, LL.M. (Cambridge)) at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Germany. Thanks to Professor David Freeman Engstrom, Abhilasha Vij, Jasmin Hohmann, Shazana Rohr, and the editorial board of the Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal for helpful comments and assistance. -

The Byline of Europe: an Examination of Foreign Correspondents' Reporting from 1930 to 1941

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 3-8-2017 The Byline of Europe: An Examination of Foreign Correspondents' Reporting from 1930 to 1941 Kerry J. Garvey Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Garvey, Kerry J., "The Byline of Europe: An Examination of Foreign Correspondents' Reporting from 1930 to 1941" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 671. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/671 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BYLINE OF EUROPE: AN EXAMINATION OF FOREIGN CORRESPONDENTS’ REPORTING FROM 1930 TO 1941 Kerry J. Garvey 133 Pages This thesis focuses on two of the largest foreign correspondents’ networks the one of the Chicago Tribune and New York Times- in prewar Europe and especially in Germany, thus providing a wider perspective on the foreign correspondents’ role in news reporting and, more importantly, how their reporting appeared in the published newspaper. It provides a new, broader perspective on how foreign news reporting portrayed European events to the American public. It describes the correspondents’ role in publishing articles over three time periods- 1930 to 1933, 1933-1939, and 1939 to 1941. Reporting and consequently the published paper depended on the correspondents’ ingenuity in the relationship with the foreign government(s); their cultural knowledge; and their gender. -

Towards a History of the Serial Killer in German Film History

FOCUS ON GERMAN STUDIES 14 51 “Warte, warte noch ein Weilchen...” – Towards a History of the Serial Killer in German Film History JÜRGEN SCHACHERL Warte, warte noch ein Weilchen, dann kommt Haarmann auch zu dir, mit dem Hackehackebeilchen macht er Leberwurst aus dir. - German nursery rhyme t is not an unknown tendency for dark events to be contained and to find expression in nursery rhymes and children’s verses, such as I the well-known German children’s rhyme above. At first instance seemingly no more than a mean, whiny playground chant, it in fact alludes to a notorious serial killer who preyed on young male prostitutes and homeless boys. Placed in this context, the possible vulgar connotations arising from Leberwurst become all the more difficult to avoid recognizing. The gravity of these events often becomes drowned out by the sing-song iambics of these verses; their teasing melodic catchiness facilitates the overlooking of their lyrical textual content, effectively down-playing the severity of the actual events. Moreover, the containment in common fairy tale-like verses serves to mythologize the subject matter, rendering it gradually more fictitious until it becomes an ahistorical prototype upon a pedestal. Serial killer and horror films have to an arguably large extent undergone this fate – all too often simply compartmentalized in the gnarly pedestal category of “gore and guts” – in the course of the respective genres’ development and propagation, particularly in the American popular film industry: Hollywood. The gravity and severity of the serial murder phenomenon become drowned in an indifferent bloody splattering of gory effects. -

Introducing the Norwegian Forum for Freedom of Expression's

66th IFLA Council and General Conference - IFLA/FAIFE Open Session - August 16, 2000, Jerusalem, Israel By Mette Newth, project leader 0. Introduction Allow me to first express my pleasure at being here. The original idea of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina database project was conceived by the Norwegian Forum for Freedom of Expression in Spring of 1997, and strongly supported by Mr. Frode Bakken, then Chairman of The Norwegian Library Association. Right from the start we hoped for co-operation with IFLA and the then emerging IFLA/FAIFE Office. All the more pleasurable to be here today, knowing that IFLA through the IFLA/FAIFE Office will be a close partner in the future development of this unique and ambitious project. A project aiming to collect and make electronically available bibliographic data on all books and newspapers censored world wide through the ages, as well as literature published on freedom of expression and censorship. Libraries remain the true memory of humanity. Our project is created in honour of the vast number of men and women whose writings for various reasons were censored through human history, - many of their books now lost forever – their ideas and thoughts in no way available to the public. Thus we regard the database also as a monument to the fundamental right of free access to information. Let me briefly introduce the Norwegian Forum for Freedom of Expression: founded in 1995 by 15 major Norwegian organisations within the media field as an independent centre of documentation and information. NFFE still remains a fairly unique constellation of organisations, representing as it does authors and translators, booksellers, libraries and publishers, journalists and editors as well as HR organisations such as P.E.N and the Norwegian Helsinki Committee. -

Censorship and Subversion in German No-Budget Horror Film Kai-Uwe Werbeck

The State vs. Buttgereit and Ittenbach: Censorship and Subversion in German No-Budget Horror Film Kai-Uwe Werbeck IN THE LATE 1980S AND EARLY 1990S, WEST GERMAN INDIE DIRECTORS released a comparatively high number of hyper-violent horror films, domestic no-budget productions often shot with camcorders. Screened at genre festivals and disseminated as grainy VHS or Betamax bootlegs, these films constitute anomalies in the history of German postwar cinema where horror films in general and splatter movies in particular have been rare, at least up until the 2000s.1 This article focuses on two of the most prominent exponents of these cheap German genre flicks: Jörg Buttgereit’s controversial and highly self- reflexive NekRomantik 2 (1991) and Olaf Ittenbach’s infamous gore-fest The Burning Moon (1992), both part of a huge but largely obscure underground culture of homebrew horror. I argue that both NekRomantik 2 and The Burning Moon—amateurish and raw as they may appear—successfully reflect the state of non-normative filmmaking in a country where, according to Germany’s Basic Law, “There shall be no censorship.”2 Yet, the nation’s strict media laws—tied, in particular, to the Jugendschutz (protection of minors)—have clearly limited the horror genre in terms of production, distribution, and reception. In this light, NekRomantik 2 and The Burning Moon become note- worthy case-studies that in various ways query Germany’s complex relation to the practice of media control after 1945. Not only do both films have an inter- esting history with regard to the idiosyncratic form of censorship practiced in postwar (West) Germany, they also openly engage with the topic by reacting to the challenges of transgressive art in an adverse cultural climate. -

International Enemy Images in Digital Games

Who Are the Enemies? The Visual Framing of Enemies in Digital Games1 BRANDON VALERIANO Reader School of Law and Politics Cardiff University PHILIP HABEL Lecturer School of Social and Politics Sciences University of Glasgow 1 We thank Andrew Stevens, Lauren Pascu, and Eduard Alveraz for research assistance. We thank Andrew Stevens, Dan Nexon, Tom Apperly, Matt Barr, Lindsay Hoffman, Greg Perreault, and Daniel Franklin for comments and suggestions. Digital games are among the most popular forms of entertainment media. Despite their ubiquity, the fields of political science and International Relations and political communication have generally overlooked the study of digital games. We take up this void by examining the international enemies depicted in combat games---specifically, first person shooter (FPS) games—which can speak to the process in the construction of international threats in society. Our review of framing the enemy gleans perspectives from multiple disciplines including International Relations, political communication, and digital gaming. Our empirical analysis traces the evolution of images in digital games from 2001 to 2013 to reveal the identity of the enemies and protagonists, and to examine the context of the game—including the setting for where each game takes place. We find that Russians are a popular form of enemy in FPS games even after considering terrorists as a broad category. Our review of the literature and our empirical analysis together present a foundation for the future study of digital games as a process of framing of enemies and transmission of threats. 2 Today digital games are ubiquitous---on our phones, tablets, laptops, and on dedicated gaming consoles and personal computers.2 Games offer an experience that is distinct and novel from other forms of entertainment in that they are possible avenues of transmission of attitudes and beliefs. -

MEADES Phd Thesis

PLAYING AGAINST THE GRAIN RHETORICS OF COUNTERPLAY IN CONSOLE BASED FIRST-PERSON SHOOTER VIDEOGAMES A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Alan Frederick Meades School of Arts, Brunel University February 2013 1 ABSTRACT Counterplay is a way of playing digital games that opposes the encoded algorithms that define their appropriate use and interaction. Counterplay is often manifested within the social arena as practices such as the creation of incendiary user generated content, grief-play, cheating, glitching, modding, and hacking. It is deemed damaging to normative play values, to the experience of play, and detrimental to the viability of videogames as mainstream entertainment products. Counterplay is often framed through the rhetoric of transgression as pathogen, as a hostile, infectious, threatening act. Those found conducting it are subject to a range of punishments ranging from expulsion from videogames to criminal conviction. Despite the steps taken to manage counterplay, it occurs frequently within contemporary videogames causing significant disruption to play and necessitating costly remedy. This thesis argues that counterplay should be understood as a practice with its own pleasures and justifying rhetorics that problematise the rhetoric of pathogen and attenuate the threat of penalty. Despite the social and economic significance of counterplay upon contemporary videogames, relatively little is known of the practices conducted by counterplayers, their motivations, or the rhetorics that they deploy to justify and contextualise their actions. Through the use of ethnographic approaches, including interview and participant observation, alongside the identification and application of five popular rhetorics of transgression, this study aims to expose the meanings and complexities of contemporary counterplay. -

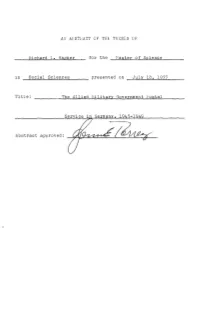

Wagner for the ~'Aster Ol..E£.Ience

AN AESTliACT OF' THE. THESIS OF' Richard L..!- Wagner for the ~'aster oL..e£.ience _ in Soc~l SCience£ presented on July 18, 1977 Title: __ The Allied tiilitary Government ~;ostal -1m Abstract approved: I~ With the collapse of the German government in May 1945, the victorious Allied powers became the rulers of Cermany. It was necessary to take control of all aspects of civil govern ment immediately. A vital part of this ~overnment was the postal system. The Allied ~ilitary Government set up the communication network needed in several steps, beginning with limited local services, and extending through special services until, on April 1, 1946, international mail was again permitted to and from Germany. This thesis traces this pattern of reestablishment. T,ocal ser vices and problems are examined, the special postal cards for displaced persons, civilian internees, prisoners of war, and members of the German Wehrmacht are explained, and the steps leading to the reopening of international mail are detailed. Close examination and attention is paid to the problems of censorship and screening of mail. The disposal of mail im pounded at the end of the war and transfer of mail between the different occupation zones and how these challenges were met by censorship authorities are presented in detail. The repatriation of displaced persons, civilian internees, prisoner of war, armed forces personnel, and other refugees through special communication programs is traced step by step, with attention focused on the many aspects of these programs. Finally, an examination of the special problem of postal issues, authorized, provisional, and unauthorized, is presented. -

The Lasting Legacy of the Red Army Faction

WEST GERMAN TERROR: THE LASTING LEGACY OF THE RED ARMY FACTION Christina L. Stefanik A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2009 Committee: Dr. Kristie Foell, Advisor Dr. Christina Guenther Dr. Jeffrey Peake Dr. Stefan Fritsch ii ABSTRACT Dr. Kristie Foell, Advisor In the 1970s, West Germany experienced a wave of terrorism that was like nothing known there previously. Most of the terror emerged from a small group that called itself the Rote Armee Fraktion, Red Army Faction (RAF). Though many guerrilla groupings formed in West Germany in the 1970s, the RAF was the most influential and had the most staying-power. The group, which officially disbanded in 1998, after five years of inactivity, could claim thirty- four deaths and numerous injuries The death toll and the various kidnappings and robberies are only part of the RAF's story. The group always remained numerically small, but their presence was felt throughout the Federal Republic, as wanted posters and continual public discourse contributed to a strong, almost tangible presence. In this text, I explore the founding of the group in the greater West German context. The RAF members believed that they could dismantle the international systems of imperialism and capitalism, in order for a Marxist-Leninist revolution to take place. The group quickly moved from words to violence, and the young West German state was tested. The longevity of the group, in the minds of Germans, will be explored in this work. -

Countering Online Hate Speech Through Legislative Measure: The

COUNTERING ONLINE HATE SPEECH THROUGH LEGISLATIVE MEASURE: THE ETHIOPIAN APPROACH IN A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE by Temelso Gashaw LLM/MA Capstone Thesis SUPERVISOR: Professor Jeremy Mcbride Central European University © Central European University CEU eTD Collection 5th of June 2020 Abstract It is almost self-evident that the phenomenon of online hate speech is on the rise. Meanwhile, governments around the world are resorting to legislative measures to tackle this pernicious social problem. This Capstone thesis has sought to offer an overview of the legislative responses to online hate speech in four different jurisdictions and unravel their implication on the right to freedom of expression. Using a comparative methodology, the research describes how the regulation of social networking platforms in relation to hate speech is being approached by the Council of Europe, German, the United States of America and Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. It tests the hypothesis that legal frameworks for moderation of user-generated online content can have a more detrimental effect for freedom of speech in semi-democratic countries like Ethiopia than in developed liberal democracies. Findings of this project regarding the recently enacted Ethiopian Hate Speech and Disinformation Prevention proclamation will offer some guidance for The Council of Ministers in the course of adopting implementing regulation. CEU eTD Collection i Table of Contents Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... -

The Advent of the Internet

The advent of the internet – and the wider digital environment – has enabled new forms of free expression, organisation and association, provided unprecedented access to information and ideas, and catalysed rapid economic and social development. It has also facilitated new forms of repression and violation of human rights, and intensified existing inequalities. Global Partners Digital (GPD) is a social purpose company dedicated to fostering a digital environment underpinned by human rights and democratic values. We do this by making policy spaces and processes more open, inclusive and transparent, and by facilitating strategic, informed and coordinated engagement in these processes by public interest actors. In this submission, we focus on the third set of questions asked by the Committee, “What is the role of social media in relation to free speech and threats to MPs?” and “How, if at all, should it be regulated?”. We have analysed and answered these questions on the basis of the international human rights framework and, where relevant, the European human rights framework. In doing so, we also touch upon the first two sets of questions which look at the relationship between the right to freedom of expression and other human rights. We also review the proposals in the government’s Online Harms White Paper given its relevance to the Committee’s inquiry. In answering this question, we look at the responsibilities that social media companies have under the international human rights framework rather than any moral obligations. As such, the starting point for determining the role that social media companies have when it comes to issues of free speech and threats to MPs is the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (the UNGPs) for they set out the agreed international framework when it comes to human rights and the private sector.