Traumatic Stress Disorder Roundtable

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SW Press Booklet PRINT3

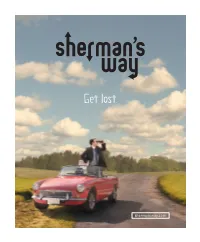

STARRY NIGHT ENTERTAINMENT Presents starring JAMES LE GROS (“The Last Winter” “Drugstore Cowboy”) ENRICO COLANTONI (“Just Shoot Me” “Galaxy Quest”) MICHAEL SHULMAN (“Can of Worms” “Little Man Tate”) BROOKE NEVIN (“The Comebacks” “Infestation”) with DONNA MURPHY THOMAS IAN NICHOLAS and LACEY CHABERT (“The Nanny Diaries”) (“American Pie Trilogy”) (“Mean Girls”) edited by CHRISTOPHER GAY cinematography by JOAQUIN SEDILLO written by TOM NANCE directed by CRAIG SAAVEDRA Copyright Sherman’s Way, LLC All Rights Reserved SHERMAN’S WAY Sherman’s Way starts with two strangers forced into a road trip of con - venience only to veer off the path into a quirky exploration of friendship, fatherhood and the annoying task of finding one’s place in the world – a world in which one wrong turn can change your destination. The discord begins when Sherman, (Michael Shulman) a young, uptight Ivy- Leaguer, finds himself stranded on the West Coast with an eccentric stranger and washed-up, middle-aged former athlete Palmer (James Le Gros) in an attempt to make it down to Beverly Hills in time for a career-making internship at a prestigious law firm. The two couldn't be more incompatible. Palmer is a reckless charmer with a zest for life; Sherman is an arrogant snob with a sense of entitlement. Palmer is con - tent reliving his past; Sherman is focused solely on his future. Neither is really living in the present. The only thing this odd couple seems to share is the refusal to accept responsibility for their lives. Director Craig Saavedra brings his witty sensibility into this poignant look at fatherhood and friendship that features indie stalwart James Le Gros in an unapologetic performance that manages to bring undeniable charm to an otherwise abrasive character. -

Twelfth Night, Helena in a Midsummer Night's Dream and Yelena In

‘MARRYING FATHER CHRISTMAS’ Cast Bios ERIN KRAKOW (Miranda) – Best known for her starring role as Elizabeth Thornton in Hallmark Channel's “When Calls the Heart,” which has been renewed for a sixth season premiering in 2019, and her recurring role on Lifetime Television’s “Army Wives,” Erin Krakow has graced both the stage and screen during her acting career. Krakow is a classically trained actor and graduated with a BFA from The Juilliard School. She had starring roles in a number of the esteemed school’s productions, including Viola and Sebastian in Twelfth Night, Helena in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Yelena in Black Russian. Beyond her work at Juilliard, Krakow has appeared in many prominent stage roles, including Cecily in The Importance of Being Earnest and Shelby in the stage adaptation of Steel Magnolias. Krakow has transitioned from stage to screen, earning series regular, recurring and guest-starring roles on top television series. On Lifetime’s “Army Wives,” Krakow played the recurring role of Specialist Tanya Gabriel. She also earned the recurring role of Molly on CBS’s hit daytime soap “Guiding Light.” Krakow guest-starred on “Castle” for ABC, “NCIS: Los Angeles” and “NCIS” for CBS and “Good Girls Revolt” for Amazon/Sony. Elizabeth Thornton on “When Calls the Heart” is not Krakow’s only beloved character for Hallmark Channel. She also played lead roles Samantha in “Chance at Romance” and Christie in “A Cookie Cutter Christmas.” On Hallmark Movies & Mysteries, Krakow played Miranda in “Finding Father Christmas” and “Engaging Father Christmas,” a role she reprises in “Marrying Father Christmas.” Born in Philadelphia, Krakow grew up in South Florida where she attended Alexander W. -

The Humor and Freshness of VERONICA MARS Arrive to HBO

The humor and freshness of VERONICA MARS arrive to HBO Starring Kristen Bell, the fourth season of this fan-favorite series premieres on June 5th, exclusively on HBO and HBO GO MIAMI, FL. May 6th, 2020 – With the fresh and sarcastic humor that characterize her, VERONICA MARS arrives to HBO and HBO GO. Starring Kristen Bell and created by writer Rob Thomas, the fourth season of this series about the clever detective premieres on June 5th. Times per country: Hbocaribbean.com In the fictional coastal community of Neptune, the rich and powerful make the rules and desperately seek to hide their dirty little secrets. Unfortunately for them, Veronica Mars, a brave and intelligent private investigator, is dedicated to solving the most complicated mysteries of this town. Season four begins when young vacationers are killed during spring break, impacting the city's tourism industry, and Mars Investigations is hired by the parents of one of the victims to find the killer. The story will follow Veronica's investigations, which are shrouded in an epic mystery that will lead her to face the powerful elites of the city. The fourth season of VERONICA MARS stars Kristen Bell, alongside Enrico Colantoni and Jason Dohring. The executive producers are Rob Thomas, Diane Ruggiero-Wright, Dan Etheridge, and Kristen Bell. The series is produced by Spondoolie Productions, in association with Warner Bros. Television. Enjoy the fourth season of VERONICA MARS exclusively on HBO and HBO GO starting on June 5th. Posted on 2020/05/06 on hbomaxlapress.com. -

Cast Bios ASHLEY WILLIAMS

‘NEVER KISS A MAN IN A CHRISTMAS SWEATER’ Cast Bios ASHLEY WILLIAMS (Maggie O’Donnell) – Ashley Williams is one of Hollywood’s most versatile actresses and continues to bring her talents to comedies and dramas in film, television and theatre. She most recently starred in the Hallmark Channel original movie “Holiday Hearts,” and in the TV Land series “The Jim Gaffigan Show,” in which she played Jeannie Gaffigan, Jim’s TV wife, who was the grounding, yet zany, wind beneath his wings. Williams also appeared alongside Jessica Chastain and Oscar Issac in the critically acclaimed film A Most Violent Year. In past years she starred in the Warner Bros. film Something Borrowed, alongside Kate Hudson and Ginnifer Goodwin. Her other film credits include the Oscar®- nominated indie Margin Call, which debuted at the Sundance Film Festival and starred Kevin Spacey, Jeremy Irons and Zachary Quinto. Williams first won over audiences as a teenager when she played Meg Ryan’s daughter, Danielle Andropoulos, on “As the World Turns.” Later, she starred alongside Mark Feuerstein in the NBC series “Good Morning Miami” and in the Lifetime telefilm “Montana Sky.” Williams also had a memorable recurring role on the comedy “How I Met Your Mother” as Victoria, “the one that got away” from Ted, played by Josh Radnor. She was so popular on the show that she won an online poll conducted by the production staff as to the character fans would most like to see the as “The Mother.” Her other television credits include recurring roles on the Holly Hunter series “Saving Grace,” “Warehouse 13” and “Huff,” as well as guest-starring roles on “FBI,” “Instinct,” “The New Adventures of Old Christine,” “Monk,” "The Mentalist,” “The Good Wife,” “Psych,” “Girls” and “Law & Order: SVU,” to name just a few. -

Actor Enrico Colantoni Pays Tribute to Catholic

ACTOR ENRICO COLANTONI PAYS TRIBUTE TO CATHOLIC EDUCATION Actor and Director Enrico Colantoni thanked Catholic educators and, in particular, the religious orders, that guided him while he attended Father Henry Carr Catholic Secondary School: his "family", as he put it. The audience of over 300 parents, students, staff, alumni and friends embraced the theme of family for the evening, joining recipients on stage for congratulations and photos. As the Chair, Angela Kennedy, remarked to the guests of the honourees: "We all need someone there to support us, to provide encouragement. It is on their shoulders that our recipients stand tonight." M.C. for the evening, Rob Gallo, brought a sense of humour to the proceedings, sharing personal and family-centered comments throughout his announcement of the awards. At one point, he brought out a selfie stick and snapped our cover photo with our Director, Angela Gauthier, with Enrico Colantoni "photo bombing" the pair from the audience who clearly enjoyed the fun. Colantoni, is a graduate of Father Henry Carr Catholic Secondary School and is an actor and director, best known for portraying Elliot DiMauro in the sitcom “Just Shoot Me”, Keith Mars on the television series “Veronica Mars” and Sergeant Greg Parker on the television series “Flashpoint” and is currently in a recurring role in iZombie. He continues to keep in touch with the TCDSB community, most recently taping a supportive video highlighting his gratitude for his Catholic education. Watch it here. The annual Awards Night, with its emphasis on family, brought out similar accolades from the honourees as they credited their families, TCDSB and Catholic education for their successes. -

Woman's Intuition

MORE THAN “JUST A HUNCH:” MEANING, FEMININE INTUITION AND TELEVISION SLEUTHS by Sheela Celeste Dominguez A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida December 2008 Copyright by Sheela Dominguez 2008 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express her sincere thanks and love to her family and friends for their loving support and encouragement throughout the writing of this thesis. The author is also grateful to her thesis advisor and committee for their patient guidance. iv ABSTRACT Author: Sheela Celeste Dominguez Title: More Than “Just a Hunch:” Meaning, Feminine Intuition and Television Sleuths Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. Christine Scodari Degree: Master of Arts Year: 2008 The rise in popularity of the female sleuth television programs makes it important to explore representations of gender and knowledge. This investigation analyzes interpretations of intuition in the television sleuth genre and relevant paratexts, examines gendered public and private spheres and raises broader questions about gendered knowledge in the series Medium, Crossing Jordan, Law and Order: Criminal Intent, Veronica Mars, Monk, The Profiler and True Calling. Rooted in feminist cultural studies, historical and sociological analysis, television and film theory and work on the detective genre, this investigation establishes common frames, or filters, through which the television sleuth genre represents intuition and the gendered experience of knowledge. Women with intuition are depicted as unstable, dangerous and mentally ill. Though framed similarly, intuitive men have more freedom. -

Financial Statements

FALL 2008 The Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists The making of The passion of page 4 58028-1 ACTRA.indd 1 8/22/08 10:23:36 AM Friends in all places Christine Webber ACTRA members and fellow supporters demanded More Canada on TV at the annual Canadian Association of Broadcasters convention. It’s not a stretch to say that from our neck of industry, was not permitted to resolve the withdrawal of the clauses in Bill C-10 that the woods we look out tension by supporting a sensible revision would grant the Minister of Heritage powers on a political world that to the bill. That would have been the smart to censor film and video works based on often appears disinter- thing for a government that is actually inter- their content. ested, and in which the opinion of creative ested in the creation of Canada’s cultural Obtaining the endorsement of the people is often treated as an annoyance. identity to do. And, it would have certainly Congress took a solid amount of work to You only have to look at the impressive won over a huge number of creative art- plan and set in motion, and all involved list of filmmakers, actors, screenwriters, ists – who have become concerned with this are to be congratulated. The result is that and producers who have shown up (at a government’s lack of interest in our culture. our resolutions for cultural action are now cost not borne by taxpayers) at the Senate Lately our creative industry seems to in the ‘Action Plan’ of the CLC. -

Productions in Ontario 2010

2010 PRODUCTION IN ONTARIO With assistance from Ontario Media Development Corporation www.omdc.on.ca FEATURE FILMS - THEATRICAL 388 ARLETTA AVENUE Company: Copperheart Entertainment Producer: Steve Hoban, Mark Smith Executive Producer: Vincenzo Natali Director: Randall Cole Production Manager: D.O.P.: Gavin Smith Key Cast: Devon Sawa, Mia Kirshner, Nick Stahl Shooting Dates: 11/8/10 – 12/8/10 A MOTHER’S SECRET Company: Sound Venture International Producer: Curtis Crawford, Stefan Wodoslawsky Executive Producer: Neil Bregman, Tom Berry Director: Gordon Yang Production Manager: Marie Allard D.O.P.: Bill St. John Key Cast: Dylan Neal, Tommie-Amber Pirie, Jon McLaren Shooting Dates: 11/27/10 – 12/17/10 BACKWOODS Company: Process Media, Foundry Films Producer: Tim Perell Director: Bart Freundlich Line Producer/Production Manager: Claire Welland Key Cast: Kristen Stewart, Julianne Moore Shooting Dates: 3/8/10 – 4/7/10 BREAKAWAY Company: Whizbang Films Inc., Don Carmody Productions, Alliance Films Producer: Frank Siracusa, Don Carmody, Ajay Virmani Executive Producer: Paul Gross, Akshay Kumar, Andre Rouleau Director: Robert Lieberman Production Manager: Andrea Raffaghello D.O.P.: Steve Danyluk Key Cast: Vinay Virmani, Al Mukadam, Russell Peters, Noureen DeWulf, Daniel DeSanto Shooting Dates: 9/2010 – 11/1/10 3/15/2013 1 COLD BLOODED Company: Cold Productions Inc. Producer: Tim Merkel, Leah Jaunzems Director: Jason Lapeyre Production Manager: Justin Kelly D.O.P.: Alwyn Kumst Shooting Dates: 12/1/10 – 12/19/10 DOWN THE ROAD AGAIN Company: Triptych Media Producer: Robin Cass Executive Producer: Sandra Cunningham, Anna Stratton Director: Donald Shebib Production Manager: Chris Pavoni D.O.P.: François Dagenais Key Cast: Doug McGrath, Kathleen Robertson, Anthony Lemke, Jayne Eastwood, Cayle Chernin, Tedde Moore Shooting Dates: 9/27/10 – 10/18/10 DREAM HOUSE Company: Morgan Creek Productions Producer: James G. -

Flashpoint Star Raises Over $2K for Actors' Fund

1000 Yonge Street Suite 301 Toronto, Ontario M4W 2K2 T 416.975.0304 1.877.399.8392 F 416.975.0306 [email protected] www.actorsfund.ca MEDIA RELEASE Flashpoint Star Enrico Colantoni’s Acting Workshop Raises Over $2,000 for Founding President Jane Mallett the Actors’ Fund of Canada President FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: April 26, 2010 Barry Flatman TORONTO – The Actors’ Fund of Canada is thrilled to announce that Enrico Colantoni, star of the hit Vice-President show, Flashpoint has donated the proceeds of an acting workshop to the Fund. The workshop was aimed Maria Topalovich at actors looking to improve their craft by learning new techniques for making artistic choices. The class quickly filled up, with eight people signed up for the sessions that took place over the course of three Secretary weekends in March. Proceeds from the workshop came to $2,200 making it a successful event for Pam Winter participants and the Actors’ Fund alike. Treasurer “Sometimes you sign on to a project that you love and have the good fortune to see it do well, but often Brian Borts, C.A. even the most fantastic project can end up nowhere due to unpredictable factors” said Mr. Colantoni. “The Actors’ Fund is a wonderful resource for everybody in our industry, helping to mitigate some of the Directors risks we take in pursuit of our art. Donating to the Fund helps to strengthen the entire community, giving Hon. Sarmite Bulte, P.C. us all a place to turn to when the unexpected happens.” Executive Director of the Fund, David Hope Christopher Dean remarked “We’re very grateful for Enrico’s generosity, the donation of his time and skills will go a long way to providing assistance to artists in crisis situations.” Hans Engel Deborah Essery The Actors' Fund of Canada is the lifeline for Canada's entertainment industry. -

TV Technoculture: the Representation of Technology in Digital Age Television Narratives Valerie Puiattiy

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2014 TV Technoculture: The Representation of Technology in Digital Age Television Narratives Valerie Puiattiy Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES TV TECHNOCULTURE: THE REPRESENTATION OF TECHNOLOGY IN DIGITAL AGE TELEVISION NARRATIVES By VALERIE PUIATTI A Dissertation submitted to the Program in Interdisciplinary Humanities in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2014 Valerie Puiatti defended this dissertation on February 3, 2014. The members of the supervisory committee were: Leigh H. Edwards Professor Directing Dissertation Kathleen M. Erndl University Representative Jennifer Proffitt Committee Member Kathleen Yancey Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, Laura and Allen, my husband, Sandro, and to our son, Emilio. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation could not have been completed without the support of many people. First, I would like to thank my advisor, Leigh H. Edwards, for her encouragement and for the thoughtful comments she provided on my chapter drafts. I would also like to thank the other committee members, Kathleen M. Erndl, Jennifer Proffitt, and Kathleen Yancey, for their participation and feedback. To the many friends who were truly supportive throughout this process, I cannot begin to say thank you enough. This dissertation would not have been written if not for Katheryn Wright and Erika Johnson-Lewis, who helped me realize on the way to New Orleans together for the PCA Conference that my presentation paper should be my dissertation topic. -

Follow Us on Twitter: @Tcdsb.Org

April 27, 2016 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Communications TCDSB AWARDS: Department ACTOR ENRICO COLANTONI TO RECEIVE ALUMNI AWARD 80 Sheppard Avenue East Toronto, Ontario Actor and Director Enrico Colantoni will be presented M2N 6E8 with a 2016 Alumni Award by the Toronto Catholic District School Board on May 2nd. Media Contact: Mary Walker Colantoni, is a graduate of Father Henry Carr Catholic Supervisor Secondary School and is an actor and director, best Communications 416.222.8282 Ext. 2302 known for portraying Elliot DiMauro in the sitcom “Just [email protected] Shoot Me”, Keith Mars on the television series “Veronica Mars” and Sergeant Greg Parker on the television series “Flashpoint” and is currently in a recurring role in www.tcdsb.org iZombie. He continues to keep in touch with the TCDSB community, most recently taping a supportive video highlighting his gratitude for his Catholic education. Follow us on watch it here Twitter: Sharing the stage with Mr. Colantoni will be Chaminade alumnus and composer @tcdsb.org Angelo Oddi, who was nominated for a Regional Emmy Award and produced the Juno-nominated album “This is Daniel Cook, Here We Are!” Joining Colantoni and Oddi is Michael Power alumnus John Paul Antonacci who has enjoyed success as a journalist. He, too, continues to live his Catholic values as an active parishioner at St. Gregory’s parish. His Honour, Mr. Justice Peter Lauwers, will be honoured with a TCDSB Award of Merit for his advocacy on behalf of Catholic education. Joining Lauwers, is former trustee and devoted Catholic, John Paul Crawford and former Superintendent of Education, John Kaposy, who humbly serves his community by bringing TCDSB retirees together for the common goal of providing financial support to youth. -

Unabridged MIPCOM 2012 Product Guide + Stills

THEEstablished in 1980 Digital Platform MIPCOM 2012 tm MIPCOM PRODUCT OF FILM Contact Us Media Kit Submission Form Magazine Editions Editorial Comments GUIDE 2012 HOME • Connect to Daily Editions @ Berlin - MIPTV - Cannes - MIPCOM - AFM BUSINESS READ The Synopsis SYNOPSISandTRAILERS.com WATCH The Trailer The One-Stop Viewing Platform CONNECT To Seller click to view Liz & Dick Available from A+E Networks MIPCOM PRODUCTPRODUCTwww.thebusinessoffilmdaily.comGUIDEGUIDE Director: Konrad Szolajski raised major questions ignored by dives with sharks in the islands of the Producer: ZK Studio Ltd comfortable lifestyles. southwest Indian Ocean. For a long time, Key Cast: Surprising, Travel, History, A WORLD TO BE FED it was a sharks' fisherman, but today it is A Human Stories, Daily Life, Humour, Documentary (52') worried about their future. 10 FRANCS Politics, Business, Europe, Ethnology Language: French 10 Francs, 28 Rue de l'Equerre, Paris, DESTINATION : ANTARTICA Delivery Status: Screening Director: Anne Guicherd Documentary (52') France 75019 France, Tel: + 2012Language: English, French Year of Production: 2010 Country of Producer: C Productions Chromatiques 33.1.487.44.377. Fax: + Director: Hervé Nicolas 33.1.487.48.265. Origin: Poland Key Cast: Environmental Issues, Producer: F Productions www.10francs.fr, [email protected] Western foreigners come to Poland to Disaster, Economy, Education, Food, Distributor experience life under communism Africa, Current Affairs, Facts, Social, Key Cast: Discovery, Travel, At MIPCOM: Christelle Quillévéré