Download This Article in PDF Format

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metallicity Relation in the Magellanic Clouds Clusters�,��,�

A&A 554, A16 (2013) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201220926 & c ESO 2013 Astrophysics Age – metallicity relation in the Magellanic Clouds clusters,, E. Livanou1, A. Dapergolas2,M.Kontizas1,B.Nordström3, E. Kontizas2,J.Andersen3,5, B. Dirsch4, and A. Karampelas1 1 Section of Astrophysics Astronomy & Mechanics, Department of Physics, University of Athens, 15783 Athens, Greece e-mail: [email protected] 2 Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics, National Observatory of Athens, PO Box 20048, 11810 Athens, Greece 3 Niels Bohr Institute Copenhagen University, Astronomical Observatory, Juliane Maries Vej 30, 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark 4 Facultad de Ciencias Astronomicas y Geofisicas, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, B1900 FWA La Plata Buenos Aires, Argentina 5 Nordic Optical Telescope, Apartado 474, 38700 Santa Cruz de La Palma, Spain Received 14 December 2012 / Accepted 2 March 2013 ABSTRACT Aims. We study small open star clusters, using Strömgren photometry to investigate a possible dependence between age and metallicity in the Magellanic Clouds (MCs). Our goals are to trace evidence of an age metallicity relation (AMR) and correlate it with the mutual interactions of the two MCs and to correlate the AMR with the spatial distribution of the clusters. In the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), the majority of the selected clusters are young (up to 1 Gyr), and we search for an AMR at this epoch, which has not been much studied. Methods. We report results for 15 LMC and 8 Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC) clusters, scattered all over the area of these galaxies, to cover a wide spatial distribution and metallicity range. The selected LMC clusters were observed with the 1.54 m Danish Telescope in Chile, using the Danish Faint Object Spectrograph and Camera (DFOSC) with a single 2k × 2k CCD. -

Multiplicity of the Red Supergiant Population in the Young Massive Cluster NGC 330

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Multiplicity of the red supergiant population in the young massive cluster NGC 330 Patrick, L.R.; Lennon, D.J.; Evans, C.J.; Sana, H.; Bodensteiner, J.; Britavskiy, N.; Dorda, R.; Herrero, A.; Negueruela, I.; de Koter, A. DOI 10.1051/0004-6361/201936741 Publication date 2020 Document Version Final published version Published in Astronomy & Astrophysics Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Patrick, L. R., Lennon, D. J., Evans, C. J., Sana, H., Bodensteiner, J., Britavskiy, N., Dorda, R., Herrero, A., Negueruela, I., & de Koter, A. (2020). Multiplicity of the red supergiant population in the young massive cluster NGC 330. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 635, [A29]. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201936741 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:25 Sep 2021 A&A 635, A29 (2020) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201936741 & c ESO 2020 Astrophysics Multiplicity of the red supergiant population in the young massive cluster NGC 330?,?? L. -

Star Clusters As Witnesses of the Evolutionary History of the Small Magellanic Cloud

JENAM, Symposium 5: Star Clusters – Witnesses of Cosmic History Star Clusters as Witnesses of the Evolutionary History of the Small Magellanic Cloud Eva K. Grebel Astronomisches Rechen-Institut 11.0Z9.2e00n8 trum für AstrGroebnel,o JEmNAMie Sy mdp.e 5:r S MUC nStairv Celusrtesrsität Heidelbe0 rg My collaborators: ! PhD student Katharina Glatt ! PhD student Andrea Kayser (both University of Basel & University of Heidelberg) ! Andreas Koch (U Basel & UCLA / OCIW) ! Jay Gallagher, D. Harbeck (U Wisc) ! Elena Sabbi (U Heidelberg & STScI) ! Antonella Nota, Marco Sirianni (STScI) ! Monica Tosi, Gisella Clementini (U Bologna) ! Andrew Cole (U Tasmania) ! Gary Da Costa (ANU) 11.09.2008 Grebel, JENAM Symp. 5: SMC Star Clusters 1 NGC 416 (OGLE) Tracers of the Age-Metallicity Relation: ! Star clusters: ! Easily identifiable. ! Chronometers of intense star formation events. ! Single-age, single-metallicity fossils of local conditions. ! Star clusters in the SMC: ! Clusters formed (and survived) for most of its lifetime " Closely spaced set of age tracers! " Unique property of the SMC. # Milky Way: No comparable set of intermediate-age, populous clusters. # LMC: Age gap at intermediate ages. 11.09.2008 Grebel, JENAM Symp. 5: SMC Star Clusters 2 Cluster-based Age-Metallicity Relation: Photometry Spectroscopy After Da Costa 2002 An inhomogeneous sample: ! Photometric and spectroscopic metallicities from different techniques ! Photometric ages from ground-/space-based data of differing depth 11.09.2008 Grebel, JENAM Symp. 5: SMC Star Clusters 3 Getting Homogeneous Ages and Metallicities: PhD thesis Katharina Glatt ! HST / ACS program to obtain deep CMDs (PI: Gallagher) $ GO 10396, 29 orbits, executed 2005 – 2006. $ 6 populous intermediate-age clusters, 1 globular cluster: NGC 419, Lindsay 38, NGC 416, 339, Kron 3, Lindsay 1, NGC 121. -

A Study of Be Stars in the Magellanic Clouds 3

A Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 1–10 (2013) Printed 27 November 2017 (MN LTEX style file v2.2) A study of Be stars in the Magellanic Clouds S. Iqbal1⋆ and S. C. Keller1† 1Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics, The Australian National University, Cotter Road, Weston Creek, ACT 2611, Australia. Received 2013 August ABSTRACT We present the results of a photometric survey for Be stars in eleven young clusters in the Large Magellanic Cloud and fourteen young clusters in the Small Magellanic Cloud. B stars with hydrogen in emission are identified on the basis of their R-Hα colour. We find that Be star fraction in clusters decreases with cluster age, and also decreases with the metallicity. Key words: early-type stars: emission-line, Be galaxies: Magellanic Clouds 1 INTRODUCTION pare the predictions of evolutionary models for early-type stars for NGC 2004 and the N 11 region on the LMC, and The transient nature of emission lines, especially those of NGC 330 and NGC 346 in the SMC. They find that their the Balmer series of hydrogen, exhibited in the spectra of nitrogen abundances are inconsistent with those predicted some B-type stars is known as the ‘Be phenomenon’. These for stars that spend most of the main-sequence lifetimes ro- spectral changes are attributed to a disk of gaseous material tating close to their critical velocity. In particular, they find surrounding the central star, the origins of which are still similar estimated nitrogen enrichment for Be and B type unclear. While recent observational data has allowed for the stars, and postulate that either Be stars rotate faster than elimination of some theoretical models (such as the wind B stars, but not at critical velocity, or that Be stars only compressed disc models of Bjorkman & Cassinelli 1993), no spend a short period (less than 10 %) of their main-sequence satisfactory mechanism for injecting material into the disk life times rotating close to critical velocity. -

Ca II Triplet Spectroscopy of Giants in SMC Star Clusters: Abundances, Velocities and the Age-Metallicity Relation

Ca II Triplet Spectroscopy of Giants in SMC Star Clusters: Abundances, Velocities and the Age-Metallicity Relation G. S. Da Costa Mount Stromlo and Siding Spring Observatories, The Australian National University, Private Bag, Weston Creek Post Office, ACT 2611, Australia Electronic mail: [email protected] and D. Hatzidimitriou Physics Department, University of Crete, P.O. Box 2208, Heraklion 710 03, Crete, Greece Electronic mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT We have obtained spectra at the Ca II triplet of individual red giants in seven SMC star clusters whose ages range from ∼4 to 12 Gyr. The spectra have been used to determine mean abundances for six of the star clusters to a typical precision of 0.12 dex. When combined with existing data for other objects, the resulting SMC age-metallicity relation is generally consistent with that for a simple model of chemical evolution, scaled to the present-day SMC mean abundance and gas mass fraction. Two of the clusters (Lindsay 113 and NGC 339), however, have abundances that are ∼0.5 dex lower than that expected from the mean age-metallicity relation. It is suggested that the formation of these clusters, which have ages of ∼5 Gyr, may have involved the infall of unenriched gas, perhaps from the Magellanic Stream. The spectra also yield radial velocities for the seven clusters. The resulting velocity dispersion is −1 arXiv:astro-ph/9802008v1 2 Feb 1998 16 ± 4 km s , consistent with those of the SMC planetary nebula and carbon star populations. Subject headings: galaxies: abundances — galaxies: individual (SMC) — galaxies: kinematics and dynamics — galaxies: star clusters — Magellanic Clouds Accepted for Publication in The Astronomical Journal – 2 – 1. -

Multiple Stellar Populations in Magellanic Cloud Clusters. VI. A

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 000–000 (0000) Printed 1 March 2018 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) Multiple stellar populations in Magellanic Cloud clusters.VI. A survey of multiple sequences and Be stars in young clusters A. P.Milone1,2, A. F. Marino2, M. Di Criscienzo3, F. D’Antona3, L.R.Bedin4, G. Da Costa2, G. Piotto1,4, M. Tailo5, A. Dotter6, R. Angeloni7,8, J.Anderson9, H. Jerjen2, C. Li10, A. Dupree6, V.Granata1,4, E. P.Lagioia1,11,12, A. D. Mackey2, D. Nardiello1,4, E. Vesperini13 1Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia “Galileo Galilei”, Univ. di Padova, Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 3, Padova, IT-35122 2Research School of Astronomy & Astrophysics, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2611, Australia 3Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica - Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma, Via Frascati 33, I-00040 Monteporzio Catone, Roma, Italy 4Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica - Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 5, Padova, IT-35122 5 Dipartimento di Fisica, Universita’ degli Studi di Cagliari, SP Monserrato-Sestu km 0.7, 09042 Monserrato, Italy 6 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, MA, USA 7 Departamento de Fisica y Astronomia, Universidad de La Serena, Av. Juan Cisternas 1200 N, La Serena, Chile 8 Instituto de Investigacion Multidisciplinar en Ciencia y Tecnologia, Universidad de La Serena, Raul Bitran 1305, La Serena, Chile 9Space Telescope Science Institute, 3800 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA 10 Department of Physics and Astronomy, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW 2109, Australia 11Instituto de Astrof`ısica de Canarias, E-38200 La Laguna, Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain 12Department of Astrophysics, University of La Laguna, E-38200 La Laguna, Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain 13Department of Astronomy, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405, USA Accepted 2018 February 27. -

Observations Centered on the Magellanic Cloud Clusters NGC 330, NGC 346, NGC 2004, and the N11 Region�,

A&A 456, 623–638 (2006) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20064988 & c ESO 2006 Astrophysics The VLT-FLAMES survey of massive stars: observations centered on the Magellanic Cloud clusters NGC 330, NGC 346, NGC 2004, and the N11 region, C. J. Evans1, D. J. Lennon2,S.J.Smartt3, and C. Trundle3 1 UK Astronomy Technology Centre, Royal Observatory Edinburgh, Blackford Hill, Edinburgh, EH9 3HJ, UK e-mail: [email protected] 2 The Isaac Newton Group of Telescopes, Apartado de Correos 321, 38700 Santa Cruz de La Palma, Canary Islands, Spain 3 Department of Physics & Astronomy, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast BT7 1NN, Northern Ireland, UK Received 9 February 2006 / Accepted 12 May 2006 ABSTRACT We present new observations of 470 stars using the Fibre Large Array Multi-Element Spectrograph (FLAMES) instrument in fields centered on the clusters NGC 330 and NGC 346 in the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC), and NGC 2004 and the N11 region in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC). A further 14 stars were observed in the N11 and NGC 330 fields using the Ultraviolet and Visual Echelle Spectrograph (UVES) for a separate programme. Spectral classifications and stellar radial velocities are given for each target, with careful attention to checks for binarity. In particular, we have investigated previously unexplored regions around the central LH9/LH10 complex of N11, finding ∼25 new O-type stars from our spectroscopy. We have observed a relatively large number of Be-type stars that display permitted Fe II emission lines. These are primarily not in the cluster cores and appear to be associated with classical Be-type stars, rather than pre main-sequence objects. -

A Bv Photometric Study of Star Clusters in Two Selected Regions of the Smc

A BV PHOTOMETRIC STUDY OF STAR CLUSTERS IN TWO SELECTED REGIONS OF THE SMC. Gonzalo Alcaino and William Liller Instituto Isaac Newton, Ministerio de Educacion de Chile, Santiago, Chile. We are deriving BV color-magnitude diagrams of star clusters in two se lected regions in the SMC. These zones, characterized by the presence of a high density of. star clusters, are centered at the 1981 coordinates for region 1: (RA: 1 10?33, Dec -73°08f), and for region 2: (RA: 1 0.33, Dec -73°00f). See Figure 1 for their identification relative to the SMC. For region 1, some of the most conspicuous clusters are: NGC 376, NGC 416, NGC 419, NGC 456, NGC 460 and NGC 465. For region 2: NGC 290, NGC 292, NGC 294, NGC 299, NGC 306, NGC 330, NGC 346, NGC 376, NGC 416 and NGC 419. Large size photographic plates (20 x 20 inches) have been obtained with the 2.5 m du Pont telescope at Las Campanas. They cover an area of 1?5 x 1?5, have a plate scale of 10.8 arc sec mm , and have been taken with a Pickering-Racine wedge (Am ^5.1 mag). The plates are now being calibrated with electronographic sequences (Walker 1972), as well as with other existing photoelectric sequences. Reference Walker, M. F.: 1972, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 159, p. 379. Figure 1. Identification chart of the SMC clusters studied (next page) 51 S. van den Bergh and K. S. de Boer (eds.), Structure and Evolution of the Magellanic Clouds, 51-52. -

Object Index

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-79134-2 - From Luminous Hot Stars to Starburst Galaxies Peter S. Conti, Paul A. Crowther and Claus Leitherer Index More information Object index 2S 0114 + 065, 141 Circinus (ESO 097–G 013), 263 4U 1700–37 (HD 153919), 140, 141 Crab Pulsar (PSR B0521 + 21), 116 4U 1907 + 097, 141 CXO J164710.2-455216, 126, 142 9 Sgr (HD 188001), 37 Cyg X-1, 141 10 Lac (HD 214680), 51, 52 Cyg X-3, 143–146 30 Doradus, see LMC Deneb (α Cyg, HD 197345), 25 α Cam (HD 30614), 63, 139 β Cep (HD 205021), 97 G5.89–0.39, 158 γ Vel (HD 68273, WR11), 18, 32, 62, 65, 132, 147, G10.30–0.15, 161 149, 151 G29.96–0.02, 157–160 ζ Oph (HD 149757), 19 G49.49–0.37 (W51A), 157 ζ Ori (HD 37742), 48 G70.29 + 1.60 (K3–50A), 163 ζ Pup (HD 66811), 18, 19, 56, 63, 83, 91–93, 139 G75.78 + 0.34, 156, 158 ζ 1 Sco (HD 152236), 64 GG Car (HD 94878), 29 η Car, see Carina nebula GRB 970228, 287 θ1 Ori C, see Orion nebula GRB 050509B, 293 µ Cep (HD 206936), 27, 29 GRB 050709, 293 ρ Cas (HD 224014), 27, 29 GRB 050904, 293 ρ Oph cluster, 165 GRB 060614, 291 τ Sco (HD 149438), 19, 46 GRO J1655–40, 139, 140 ω Cen, 248 Gum nebula, 184 GX 301–2, 140, 141 AF star, 44 AG Car (HD 94910), 25–27, 59, 64, 192, 193 Haro 11 (ESO 350–IG 038), 227, 228 Antares (α Sco, HD 148478), 29 HD 16523 (WR4), 66 Antennae galaxies (NGC4038/9), 167, 175, 176, 179 HD 45677, 28 Arches cluster, 166, 174, 175, 247 HD 50896 (WR6), 48, 75 HD 64760, 90 ◦ BD + 40 4220, 130 HD 93129A, see Carina nebula Betelgeuse (α Ori, HD 39801), 29, 58–61 HD 96548 (WR40), 56 Bubble nebula (NGC 7635), 191–192 -

Southern Objects Paging

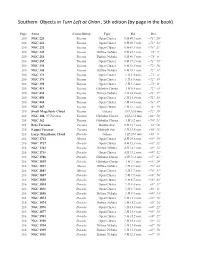

Southern Objects in Turn Left at Orion , 5th edition (by page in the book) Page Name Constellation Type RA Dec. 210 NGC 220 Tucana Open Cluster 0 H 40.5 min. −73° 24' 210 NGC 222 Tucana Open Cluster 0 H 40.7 min. −73° 23' 210 NGC 231 Tucana Open Cluster 0 H 41.1 min. −73° 21' 210 NGC 249 Tucana Diffuse Nebula 0 H 45.5 min. −73° 5' 210 NGC 261 Tucana Diffuse Nebula 0 H 46.5 min. −73° 6' 210 NGC 265 Tucana Open Cluster 0 H 47.2 min. −73° 29' 210 NGC 330 Tucana Open Cluster 0 H 56.3 min. −72° 28' 210 NGC 346 Tucana Diffuse Nebula 0 H 59.1 min. −72° 11' 210 NGC 371 Tucana Open Cluster 1 H 3.4 min. −72° 4' 210 NGC 376 Tucana Open Cluster 1 H 3.9 min. −72° 49' 210 NGC 395 Tucana Open Cluster 1 H 5.1 min. −72° 0' 210 NGC 419 Tucana Globular Cluster 1 H 8.3 min −72° 53' 210 NGC 456 Tucana Diffuse Nebula 1 H 14.4 min. −73° 17' 210 NGC 458 Tucana Open Cluster 1 H 14.9 min. −71° 33' 210 NGC 460 Tucana Open Cluster 1 H 14.6 min. −73° 17' 210 NGC 465 Tucana Open Cluster 1 H 15.7 min. −73° 19' 210 Small Magellanic Cloud Tucana Galaxy 0 H 53.0 min −72° 50' 212 NGC 104, 47 Tucanae Tucana Globular Cluster 0 H 24.1 min −62° 58' 214 NGC 362 Tucana Globular Cluster 1 H 3.2 min −70° 51' 215 Beta Tucanae Tucana Double Star 0 H 31.5 min. -

The Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment. Age of Star Clusters

ACTA ASTRONOMICA Vol. 49 (1999) pp. 157±164 The Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment. Age of Star Clusters from the SMC by G. P i e t r z y n s k i, and A. Udalski Warsaw University Observatory, Al. Ujazdowskie 4, 00-478 Warszawa, Poland e-mail: (pietrzyn,udalski)@sirius.astrouw.edu.pl Received May 4, 1999 ABSTRACT We present determination of age of clusters from 2.4 square degree region of the SMC bar. The photometric data were taken from the BVI maps of the SMC and catalog of clusters in this galaxy obtained during the OGLE-II microlensing survey. For 93 well populated SMC clusters their age is derived with the standard procedure of isochrone ®tting. The distribution of age of cluster from the SMC is presented. It indicates either non-uniform process of cluster formation or very effective disruption of clusters. Key words: Magellanic Clouds ± Galaxies: star clusters. 1. Introduction Studies of star clusters provide important information about parent galaxy and processesconnectedwith their formation and evolution. The rich systemof clusters from the SMC is especially well suited for such investigations. In particular, based on the age distribution of clusters one can look into the cluster formation history and obtain information on processes of cluster formation and disruption. Unfortunately the SMC was neglected photometrically for years. Until recently only a few papers presented precise photometric data obtained with modern obser- vational techniques for clusters from this galaxy. A few old clusters from the SMC were studied using the HST telescope (Mighell et al. 1998). Analysis of other SMC clusters can be found very sporadically in the literature. -

Structures in Surface-Brightness Profiles of LMC and SMC Star Clusters: Evidence of Mergers?

A&A 485, 71–80 (2008) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20079298 & c ESO 2008 Astrophysics Structures in surface-brightness profiles of LMC and SMC star clusters: evidence of mergers? L. Carvalho1,T.A.Saurin1,E.Bica1,C.Bonatto1, and A. A. Schmidt2 1 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Departamento de Astronomia, CP 15051, RS, Porto Alegre 91501-970, Brazil e-mail: [luziane;bica;charles]@if.ufrgs.br; [email protected] 2 Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, LANA, RS, Santa Maria 97119-900, Brazil e-mail: [email protected] Received 20 December 2007 / Accepted 2 April 2008 ABSTRACT Context. The LMC and SMC are rich in binary star clusters, and some mergers are expected. It is thus important to characterise single clusters, binary clusters and candidates for mergers. Aims. We selected a sample of star clusters in each Cloud with this aim. Surface photometry of 25 SMC and 22 LMC star clusters was carried with the ESO Danish 1.54 m telescope. 23 clusters were observed for the first time for these purposes. Methods. We fitted Elson, Fall and Freeman (EFF) profiles to the data, deriving structural parameters, luminosities and masses. We also use isophotal maps to constrain candidates for cluster interactions. Results. The structural parameters, luminosities and masses presented good agreement with those in the literature. Three binary clusters in the sample have a double profile. Four clusters (NGC 376, K 50, K 54 and NGC 1810) do not have companions and present important deviations from EFF profiles. Conclusions. The present sample contains blue and red Magellanic clusters.