Title & Imprint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Markandeya Puran

MARKANDEYA PURAN ENGLISH INTRODUCTION Once Jaimini, a disciple of sage Veda Vyasa expressed his curiosity before Markand e'Oya - Lord! In the great epic Mahabharata, which was created by Veda Vyasa, description of Dharm,a Arth, Kama and Moksha appears to be intertwined at times and at other times, it appears to be separate from one another. Veda Vyasa had described the norms, the stages and the means to perform the duties in all the four stages. This epic contains cryptic knowledge of Vedas. Hence O great sage! I have approached you in order to grasp the full knowledge contained in Mahabharata with your help. Why did Lord take human incarnation even though He is the cause of the origin, perpetuation and destruction of the universe? How did Draupadi become the wife of five Pandavas? How did Balarama expiate for the sin of killing a Brahmin? How did Draupadi's sons give up their lives? Kindly narrate all these things in detail. ' Markandeya says- 'O Muni! Presently I am engaged in evening worship. Hence I do hnaovt e time to narrate these things in detail. But I am telling you about the birds which will narrate you the entire content of Mahabharata. Those birds will also remove all your doubts. Sons of the great bird Drona- Pingaksha, Vibodha, Suputra, Sumuk etc. stay in the caves among the hills of Vindhyachal. They are proficient in Vedas. Go and ask them, they will remove all your doubts.' Markandeya's words surprised Jaimini. To confirm, he asked again- 'It is surprising that the birds could narrate the content of Mahabharata just like human beings. -

The Upanishads Page

TThhee UUppaanniisshhaaddss Table of Content The Upanishads Page 1. Katha Upanishad 3 2. Isa Upanishad 20 3 Kena Upanishad 23 4. Mundaka Upanishad 28 5. Svetasvatara Upanishad 39 6. Prasna Upanishad 56 7. Mandukya Upanishad 67 8. Aitareya Upanishad 99 9. Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 105 10. Taittiriya Upanishad 203 11. Chhandogya Upanishad 218 Source: "The Upanishads - A New Translation" by Swami Nikhilananda in four volumes 2 Invocation Om. May Brahman protect us both! May Brahman bestow upon us both the fruit of Knowledge! May we both obtain the energy to acquire Knowledge! May what we both study reveal the Truth! May we cherish no ill feeling toward each other! Om. Peace! Peace! Peace! Katha Upanishad Part One Chapter I 1 Vajasravasa, desiring rewards, performed the Visvajit sacrifice, in which he gave away all his property. He had a son named Nachiketa. 2—3 When the gifts were being distributed, faith entered into the heart of Nachiketa, who was still a boy. He said to himself: Joyless, surely, are the worlds to which he goes who gives away cows no longer able to drink, to eat, to give milk, or to calve. 4 He said to his father: Father! To whom will you give me? He said this a second and a third time. Then his father replied: Unto death I will give you. 5 Among many I am the first; or among many I am the middlemost. But certainly I am never the last. What purpose of the King of Death will my father serve today by thus giving me away to him? 6 Nachiketa said: Look back and see how it was with those who came before us and observe how it is with those who are now with us. -

L CHNOS Årsbok För Idé- Och Lärdomshistoria

L CHNOS Årsbok för idé- och lärdomshistoria Annual of the Swedish History of Science Society Synen på studieresande i Sverige under 1600- och 1700-talet 1 LYCHNOS Utgiven av Lärdomshistoriska Samfundet med stöd av Vetenskapsrådet Redaktör/Editor Sven Widmalm Recensionsredaktörer/Review editors Frans Lundgren Mathias Persson Redaktionskommitté/Editorial committee Gunnar Broberg, Karin Johannisson, Sven-Eric Liedman, Bo Lindberg, Svante Lindqvist, Bosse Sundin Tidigare redaktörer/Former editors Johan Nordström 1936–1949 Sten Lindroth 1950–1980 Gunnar Eriksson 1980–1990 Karin Johannisson 1990–2000 Redaktionens adress / Edirorial address Avd. för vetenskapshistoria Box 629, 751 26 Uppsala Omslagsbild Såningsmannen 6–5 (1907) © 2005 Lärdomshistoriska Samfundet och författarna ISBN 91-85286-559 ISSN 0076-1648 Production Svensk Bokform, Torna Hällestad 2005 Printed in Latvia by Preses Nams, Riga 2005 2 Aron Sjöblad Innehåll Uppsatser/ Papers 9 Recovering the Codex Argenteus Simon McKeown Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie, David Klöcker Ehrenstrahl and Wulfila’s Gothic Bible Summary: Recovering the Codex Argenteus: Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie, David Klöcker Ehrenstrahl, and Wulfila’s Gothic Bible 29 Törnrosa och myten Peter Jackson Vetenskapshistoriska ledtrådar i Kinder- und Hausmärchen Summary: Sleeping Beauty and myth: Clues to a history of scholarship in Kinder- und Hausmärchen 43 Nordens koordinater Hendriette Kliemann Vetenskapliga konstruktioner av en europeisk region 1770–1850 Summary: The coordinates of the North: Scientific constructions of an European region 1770–1850. 63 Transformasjon av liv? Thomas Dahl Rudolf Virchows oppgjør med teorien om livskraft og etableringen av den vitenskapelige medisinen Summary: Transforming life?: Rudolf Virchow’s critique of the theory of life force and the establishment of scientific medicine 87 Kanslern och den akademiska friheten Carl Frängsmyr Striderna vid den juridiska fakulteten i Uppsala under 1850-talet Summary: The chancellor and academic freedom: Discord in the Faculty of Law at Uppsala in the 1850s. -

Private Sector

The Memory Keeper's Daughter Kim Edwards PENGUIN BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R oRL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen's Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi — 110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R oRL, England First published in the United States of America by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. 2005 Published in Penguin Books 2006 11 13 15 17 19 20 18 16 14 12 Copyright © Kim Edwards, 2005 All rights reserved publisher's note This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. ISBNo 14 30.3714 5 CIP data available Printed in the United States of America Designed by Carlo. Bolte • Set in Granjon Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4 This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4 Books 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18 Translator: Kisari Mohan Ganguli Release Date: March 26, 2005 [EBook #15477] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MAHABHARATA VOL 4 *** Produced by John B. Hare. Please notify any corrections to John B. Hare at www.sacred-texts.com The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa BOOK 13 ANUSASANA PARVA Translated into English Prose from the Original Sanskrit Text by Kisari Mohan Ganguli [1883-1896] Scanned at sacred-texts.com, 2005. Proofed by John Bruno Hare, January 2005. THE MAHABHARATA ANUSASANA PARVA PART I SECTION I (Anusasanika Parva) OM! HAVING BOWED down unto Narayana, and Nara the foremost of male beings, and unto the goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered. "'Yudhishthira said, "O grandsire, tranquillity of mind has been said to be subtile and of diverse forms. I have heard all thy discourses, but still tranquillity of mind has not been mine. In this matter, various means of quieting the mind have been related (by thee), O sire, but how can peace of mind be secured from only a knowledge of the different kinds of tranquillity, when I myself have been the instrument of bringing about all this? Beholding thy body covered with arrows and festering with bad sores, I fail to find, O hero, any peace of mind, at the thought of the evils I have wrought. -

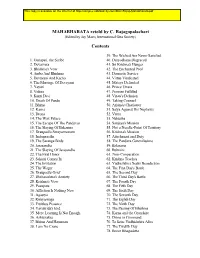

Rajaji-Mahabharata.Pdf

MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, International Gita Society) Contents 39. The Wicked Are Never Satisfied 1. Ganapati, the Scribe 40. Duryodhana Disgraced 2. Devavrata 41. Sri Krishna's Hunger 3. Bhishma's Vow 42. The Enchanted Pool 4. Amba And Bhishma 43. Domestic Service 5. Devayani And Kacha 44. Virtue Vindicated 6. The Marriage Of Devayani 45. Matsya Defended 7. Yayati 46. Prince Uttara 8. Vidura 47. Promise Fulfilled 9. Kunti Devi 48. Virata's Delusion 10. Death Of Pandu 49. Taking Counsel 11. Bhima 50. Arjuna's Charioteer 12. Karna 51. Salya Against His Nephews 13. Drona 52. Vritra 14. The Wax Palace 53. Nahusha 15. The Escape Of The Pandavas 54. Sanjaya's Mission 16. The Slaying Of Bakasura 55. Not a Needle-Point Of Territory 17. Draupadi's Swayamvaram 56. Krishna's Mission 18. Indraprastha 57. Attachment and Duty 19. The Saranga Birds 58. The Pandava Generalissimo 20. Jarasandha 59. Balarama 21. The Slaying Of Jarasandha 60. Rukmini 22. The First Honor 61. Non-Cooperation 23. Sakuni Comes In 62. Krishna Teaches 24. The Invitation 63. Yudhishthira Seeks Benediction 25. The Wager 64. The First Day's Battle 26. Draupadi's Grief 65. The Second Day 27. Dhritarashtra's Anxiety 66. The Third Day's Battle 28. Krishna's Vow 67. The Fourth Day 29. Pasupata 68. The Fifth Day 30. Affliction Is Nothing New 69. The Sixth Day 31. Agastya 70. The Seventh Day 32. Rishyasringa 71. The Eighth Day 33. Fruitless Penance 72. The Ninth Day 34. Yavakrida's End 73. -

Yogavaasishta the Calm Down

YOGAVAASISHTA Part V THE CALM DOWN 1. Background: We had seen in Prat II and III of our Series on Yogavaasishta that the venerated Vedic dictum: “Yatovaa imani bhutani jaayante Yena jaataani jeevanti” - Taittiriya Upanishad was the fundamental principle based on which Sage Vasishta designed the course of his talks in imparting philosophical wisdom to Lord Rama. After an opening discussion as an introductory to the subjects of detachment and intense longing for liberation, (Part I of this Series on Yogavaasishta), the sage dealt with Origination (Utpatti) of the visible universe (Jagat) and later its Sustenance (Sthiti) in accordance with the above scriptural statement. In the chapter on Creation (Part II in this Series) it was maintained that the origination of the universe was purely incidental to the mind of the onlooker. In the chapter on Sustenance (Part III in this Series) it was established that the universe draws its sustenance also from mind. Now it remains to be shown that the dissolution of the universe too is dependent on the mind of the seer. But could the dissolution, i.e. ending of the universe, depend on mind? If mind at all exists, the universe inevitably follows it one way or other - either by origination or by sustenance. So there is no possibility of the universe being annulled by the mind if the mind manages to continue its existence. For this reason it was repeatedly pointed out in the earlier chapters (refer to Part II and III of Yogavaasishta) that the universe would end only when the mind ended and there was no other way to dissolve the universe. -

Page 1 of 28 Garuda Purana

Garuda Purana Page 1 of 28 Garuda Purana LORD VISHNU'S INCARNATIONS Sutji once reached Naimisharanya in course of his pilgrimage. There he found numerous sages engaged in austerities and penance. All of them were delighted to find Sutji in their midst and considered it as a God sent opportunity to get their doubts related with religious topics cleared. Sage Shaunak was also present there and he asked Sutji --' O revered sage! Who is the creator of this world? Who nurtures it and who annihilates it in the end? How can one realize the supreme Almighty? How many incarnations the Almighty has taken till now? Please enlighten us on all these things, which are shrouded in mystery.' Sutji replied--' I am going to reveal to you the contents of Garuda Puran, which contains the divine tales of Lord Vishnu. This particular Puran is named after Garuda because he was the one who first narrated these tales to sage Kashyap. Kashyap subsequently narrated them to sage Vyas. I came to know about these divine tales from sage Vyas. Lord Vishnu is the supreme almighty and the source of all creations. He is the nurturer of this world and the annihilator as well. Though he is beyond the bondage of birth and death yet he takes incarnations to protect the world from the tyranny of sinners. His first incarnation was in the form of the eternal adolescent Sanat kumar and others who were all celibates and extremely virtuous.' 'Lord Vishnu took his second incarnation in the form of a boar (Varah) to protect the Earth from the mighty demon named Hiranyaksha, who had abducted her to Patal loka (Nether world). -

Participatory Propaganda Model 1

A PARTICIPATORY PROPAGANDA MODEL 1 Participatory Propaganda: The Engagement of Audiences in the Spread of Persuasive Communications Alicia Wanless Michael Berk Director of Strategic Communications, Visiting Research Fellow, SecDev Foundation Centre for Cyber Security and International [email protected] Relations Studies, University of Florence [email protected] Paper presented at the "Social Media & Social Order, Culture Conflict 2.0" conference organized by Cultural Conflict 2.0 and sponsored by the Research Council of Norway on 1 December 2017, Oslo. To be published as part of the conference proceedings in 2018. A PARTICIPATORY PROPAGANDA MODEL 2 Abstract Existing research on aspects of propaganda in a digital age tend to focus on isolated techniques or phenomena, such as fake news, trolls, memes, or botnets. Providing invaluable insight on the evolving human-technology interaction in creating new formats of persuasive messaging, these studies lend to an enriched understanding of modern propaganda methods. At the same time, the true effects and magnitude of successful influencing of large audiences in the digital age can only be understood if target audiences are perceived not only as ‘objects’ of influence, but as ‘subjects’ of persuasive communications as well. Drawing from vast available research, as well as original social network and content analyses conducted during the 2016 U.S. presidential elections, this paper presents a new, qualitatively enhanced, model of modern propaganda – “participatory propaganda” - and discusses its effects on modern democratic societies. Keywords: propaganda, Facebook, social network analysis, content analysis, politics A PARTICIPATORY PROPAGANDA MODEL 3 Participatory Propaganda: The Engagement of Audiences in the Spread of Persuasive Communications Rapidly evolving information communications technologies (ICTs) have drastically altered the ways individuals engage in the public information domain, including news ways of becoming subjected to external influencing. -

The Life of Vidura

Çré Padminé Ekädaçé Issue no: 15 28th June 2015 THe Life of Vidura Features THE BIRTH OF VIDURA Mahäbhärata ANIMANDAVYA CURSES YAMARAJA Mahäbhärata NO ONE EQUAL TO VIDURA Mahäbhärata PARTIALITY TOWARDS THE PANDAVAS Mahäbhärata VIDURA GOES FOR PILGRIMAGE Srila Sukadeva Goswami VIDURA’S RETURNING TO HASTINAPUR Srila Suta Goswami VIDURA WAS NEVER A ÇÜDRA His Divine Grace A .C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada Issue no 15, Page — 2 nityaà bhägavata-sevayä princess was still struck with horror when the grim ascetic approached her. She turned pale with fright, although she kept her eyes open as Srila Vyasdeva and Mother Satyavati Srila Vyasdeva she conceived. Ambika gave birth to a blind child who was named Dhritarashtra. Ambalika delivered a pale child who was nevertheless effulgent and endowed with many auspicious marks on his body, and who was named Pandu in accord with Vyasadeva’s words. Soon after, the sage again came to the palace in order to approach Ambika for a second time. The queen was alarmed at the prospect of meeting again with the terrible-looking åñi. She went to a maidservant who was an intimate friend and asked that she take her place. Giving the servant her own ornaments and adorning her with the finest robes, she had her wait in the bedchamber for the sage. Although he knew everything the åñi entered the chamber as before. As soon as she saw the exalted sage the maidservant rose up respectfully. She bowed at his feet and had him THE BIRTH OF VIDURA sit down comfortably. After gently washing Sri Vaisampayana Muni his feet, the girl offered him many kinds of delicious foodstuffs. -

Inventive Linguistics Sandrine Sorlin

Inventive Linguistics Sandrine Sorlin To cite this version: Sandrine Sorlin. Inventive Linguistics. France. Presses universitaires de la Méditerranée, 216 p., 2011, Sciences du langage, 978-2-84269-908-6. halshs-01271311 HAL Id: halshs-01271311 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01271311 Submitted on 21 Jul 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. PĹrĂeŊsŇsĂeŊŽ ĹuŠnĹiŠvČeĽrŇsĹiĹtĄaĹiĹrĂeŊŽ ĂdĂe ĎlĄaĞ MĂéĄdĹiĹtĄeĽrĹrĂaŠnĂéĄe— UŢnĂe ĂqĹuĂeŊsĹtĽiĂoŤn? UŢnĞ ŇpĹrĂoĘbĘlĄèŞmĂe? TĂéĚlĄéŊpŘhĂoŤnĂeĽz ĂaĹuĞ 04 99 63 69 23 ĂoŁuĞ 27. SORLINDĹuĎlĽiĹtĽtĄeĽrĂaĹiĹrĂeOK — DĂéŊpĂaĹrĹt ĹiŠmŇpĹrĹiŠmĂeĽrĹiĂe — 2010-11-15 — 10 ŘhĞ 28 — ŇpĂaĂgĄe 1 (ŇpĂaĂgĽiŠnĂéĄe 1) ŇsĹuĹrĞ 216 PĹrĂeŊsŇsĂeŊŽ ĹuŠnĹiŠvČeĽrŇsĹiĹtĄaĹiĹrĂeŊŽ ĂdĂe ĎlĄaĞ MĂéĄdĹiĹtĄeĽrĹrĂaŠnĂéĄe— UŢnĂe ĂqĹuĂeŊsĹtĽiĂoŤn? UŢnĞ ŇpĹrĂoĘbĘlĄèŞmĂe? TĂéĚlĄéŊpŘhĂoŤnĂeĽz ĂaĹuĞ 04 99 63 69 23 ĂoŁuĞ 27. SORLINDĹuĎlĽiĹtĽtĄeĽrĂaĹiĹrĂeOK — DĂéŊpĂaĹrĹt ĹiŠmŇpĹrĹiŠmĂeĽrĹiĂe — 2010-11-15 — 10 ŘhĞ 28 — ŇpĂaĂgĄe 2 (ŇpĂaĂgĽiŠnĂéĄe 2) ŇsĹuĹrĞ 216 PĹrĂeŊsŇsĂeŊŽ ĹuŠnĹiŠvČeĽrŇsĹiĹtĄaĹiĹrĂeŊŽ ĂdĂe ĎlĄaĞ MĂéĄdĹiĹtĄeĽrĹrĂaŠnĂéĄe—