Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pomegranate Cycle

The Pomegranate Cycle: Reconfiguring opera through performance, technology & composition By Eve Elizabeth Klein Bachelor of Arts Honours (Music), Macquarie University, Sydney A PhD Submission for the Department of Music and Sound Faculty of Creative Industries Queensland University of Technology Brisbane, Australia 2011 ______________ Keywords Music. Opera. Women. Feminism. Composition. Technology. Sound Recording. Music Technology. Voice. Opera Singing. Vocal Pedagogy. The Pomegranate Cycle. Postmodernism. Classical Music. Musical Works. Virtual Orchestras. Persephone. Demeter. The Rape of Persephone. Nineteenth Century Music. Musical Canons. Repertory Opera. Opera & Violence. Opera & Rape. Opera & Death. Operatic Narratives. Postclassical Music. Electronica Opera. Popular Music & Opera. Experimental Opera. Feminist Musicology. Women & Composition. Contemporary Opera. Multimedia Opera. DIY. DIY & Music. DIY & Opera. Author’s Note Part of Chapter 7 has been previously published in: Klein, E., 2010. "Self-made CD: Texture and Narrative in Small-Run DIY CD Production". In Ø. Vågnes & A. Grønstad, eds. Coverscaping: Discovering Album Aesthetics. Museum Tusculanum Press. 2 Abstract The Pomegranate Cycle is a practice-led enquiry consisting of a creative work and an exegesis. This project investigates the potential of self-directed, technologically mediated composition as a means of reconfiguring gender stereotypes within the operatic tradition. This practice confronts two primary stereotypes: the positioning of female performing bodies within narratives of violence and the absence of women from authorial roles that construct and regulate the operatic tradition. The Pomegranate Cycle redresses these stereotypes by presenting a new narrative trajectory of healing for its central character, and by placing the singer inside the role of composer and producer. During the twentieth and early twenty-first century, operatic and classical music institutions have resisted incorporating works of living composers into their repertory. -

Vocality and Listening in Three Operas by Luciano Berio

Clare Brady Royal Holloway, University of London The Open Voice: Vocality and Listening in three operas by Luciano Berio Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music February 2017 The Open Voice | 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Patricia Mary Clare Brady, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: February 1st 2017 The Open Voice | 2 Abstract The human voice has undergone a seismic reappraisal in recent years, within musicology, and across disciplinary boundaries in the humanities, arts and sciences; ‘voice studies’ offers a vast and proliferating array of seemingly divergent accounts of the voice and its capacities, qualities and functions, in short, of what the voice is. In this thesis, I propose a model of the ‘open voice’, after the aesthetic theories of Umberto Eco’s seminal book ‘The Open Work’ of 1962, as a conceptual framework in which to make an account of the voice’s inherent multivalency and resistance to a singular reductive definition, and to propose the voice as a site of encounter and meaning construction between vocalist and receiver. Taking the concept of the ‘open voice’ as a starting point, I examine how the human voice is staged in three vocal works by composer Luciano Berio, and how the voice is diffracted through the musical structures of these works to display a multitude of different, and at times paradoxical forms and functions. In Passaggio (1963) I trace how the open voice invokes the hegemonic voice of a civic or political mass in counterpoint with the particularity and frailty of a sounding individual human body. -

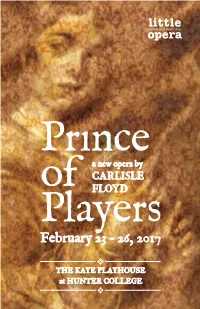

View the Program!

cast EDWARD KYNASTON Michael Kelly v Shea Owens 1 THOMAS BETTERTON Ron Loyd v Matthew Curran 1 VILLIERS, DUKE OF BUCKINGHAM Bray Wilkins v John Kaneklides 1 MARGARET HUGHES Maeve Höglund v Jessica Sandidge 1 LADY MERESVALE Elizabeth Pojanowski v Hilary Ginther 1 about the opera MISS FRAYNE Heather Hill v Michelle Trovato 1 SIR CHARLES SEDLEY Raùl Melo v Set in Restoration England during the time of King Charles II, Prince of Neal Harrelson 1 Players follows the story of Edward Kynaston, a Shakespearean actor famous v for his performances of the female roles in the Bard’s plays. Kynaston is a CHARLES II Marc Schreiner 1 member of the Duke’s theater, which is run by the actor-manager Thomas Nicholas Simpson Betterton. The opera begins with a performance of the play Othello. All of NELL GWYNN Sharin Apostolou v London society is in attendance, including the King and his mistress, Nell Angela Mannino 1 Gwynn. After the performance, the players receive important guests in their HYDE Daniel Klein dressing room, some bearing private invitations. Margaret Hughes, Kynaston’s MALE EMILIA Oswaldo Iraheta dresser, observes the comings and goings of the others, silently yearning for her FEMALE EMILIA Sahoko Sato Timpone own chance to appear on the stage. Following another performance at the theater, it is revealed that Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, has long been one STAGE HAND Kyle Guglielmo of Kynaston’s most ardent fans and admirers. SAMUEL PEPYS Hunter Hoffman In a gathering in Whitehall Palace, Margaret is presented at court by her with Robert Balonek & Elizabeth Novella relation Sir Charles Sedley. -

Floyd's Susannah

Baltimore Concert Opera presents: Floyd’s Susannah Who is Carlisle Floyd? The Gist of the Story: Setting: New Hope Valley, Tennessee in the mid 20th century; loosely inspired by the Apocryphal tale of Susannah and the Elders WHO? Set in the 1950s in the backwoods of Tennessee Composer and Librettist: hill country, the opera centers on 18-year-old Susannah, who faces hostility from women in Carlisle Floyd her church community for her beauty and the (born June 11, 1926) attention it attracts from their husbands. As she innocently bathes in a nearby creek one day, the WHAT? church elders spy on Susannah, and their own lustful impulses drive them to accuse her of sin Floyd called this operatic and seduction. Among these hypocrites is the creation a ‘musical drama,’ newly-arrived Reverend Olin Blitch, whose focusing on both music and own inner darkness leads to heart-wrenching Born in South Carolina to a piano teacher and a text to tell the story. tragedy for Susannah. Dealing with the Methodist minister, Carlisle Floyd developed an dramatic themes of jealousy, gossip, and interest in music early on. Studying creative ‘group-think’ -- and filled with soaring folk- writing, piano and then coming to composition, WHEN? inspired melodies -- this opera has been a he found himself teaching at Florida State Premiered on favorite of opera-goers for many years. University in the mid 1950s. Always one to February 24, 1955 The Characters write both the music and texts for his operas, he (62 years prior to our believes that this process gives him greater REV. -

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Phyllis Curtin - Box 1 Folder# Title: Photographs Folder# F3 Clothes by Worth of Paris (1900) Brooklyn Academy F3 F4 P.C. recording F4 F7 P. C. concert version Rosenkavalier Philadelphia F7 FS P.C. with Russell Stanger· FS F9 P.C. with Robert Shaw F9 FIO P.C. with Ned Rorem Fl0 F11 P.C. with Gerald Moore Fl I F12 P.C. with Andre Kostelanetz (Promenade Concerts) F12 F13 P.C. with Carlylse Floyd F13 F14 P.C. with Family (photo of Cooke photographing Phyllis) FI4 FIS P.C. with Ryan Edwards (Pianist) FIS F16 P.C. with Aaron Copland (televised from P.C. 's home - Dickinson Songs) F16 F17 P.C. with Leonard Bernstein Fl 7 F18 Concert rehearsals Fl8 FIS - Gunther Schuller Fl 8 FIS -Leontyne Price in Vienna FIS F18 -others F18 F19 P.C. with hairdresser Nina Lawson (good backstage photo) FI9 F20 P.C. with Darius Milhaud F20 F21 P.C. with Composers & Conductors F21 F21 -Eugene Ormandy F21 F21 -Benjamin Britten - Premiere War Requiem F2I F22 P.C. at White House (Fords) F22 F23 P.C. teaching (Yale) F23 F25 P.C. in Tel Aviv and U.N. F25 F26 P. C. teaching (Tanglewood) F26 F27 P. C. in Sydney, Australia - Construction of Opera House F27 F2S P.C. in Ipswich in Rehearsal (Castle Hill?) F2S F28 -P.C. in Hamburg (large photo) F2S F30 P.C. in Hamburg (Strauss I00th anniversary) F30 F31 P. C. in Munich - German TV F31 F32 P.C. -

Francesco Cavalli One Man. Two Women. Three Times the Trouble

GIASONE FRANCESCO CAVALLI ONE MAN. TWO WOMEN. THREE TIMES THE TROUBLE. 1 Pinchgut - Giasone Si.indd 1 26/11/13 1:10 PM GIASONE MUSIC Francesco Cavalli LIBRETTO Giacinto Andrea Cicognini CAST Giasone David Hansen Medea Celeste Lazarenko Isiile ORLANDO Miriam Allan Demo BY GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL Christopher Saunders IN ASSOCIATION WITH GLIMMERGLASS FESTIVAL, NEW YORK Oreste David Greco Egeo Andrew Goodwin JULIA LEZHNEVA Delfa Adrian McEniery WITH THE TASMANIAN SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Ercole Nicholas Dinopoulos Alinda Alexandra Oomens XAVIER SABATA Argonauts Chris Childs-Maidment, Nicholas Gell, David Herrero, WITH ORCHESTRA OF THE ANTIPODES William Koutsoukis, Harold Lander TOWN HALL SERIES Orchestra of the Antipodes CONDUCTOR Erin Helyard CLASS OF TIMO-VEIKKO VALVE DIRECTOR Chas Rader-Shieber LATITUDE 37 DESIGNERS Chas Rader-Shieber & Katren Wood DUELLING HARPSICHORDS ’ LIGHTING DESIGNER Bernie Tan-Hayes 85 SMARO GREGORIADOU ENSEMBLE HB 5, 7, 8 and 9 December 2013 AND City Recital Hall Angel Place There will be one interval of 20 minutes at the conclusion of Part 1. FIVE RECITALS OF BAROQUE MUSIC The performance will inish at approximately 10.10 pm on 5x5 x 5@ 5 FIVE TASMANIAN SOLOISTS AND ENSEMBLES Thursday, Saturday and Monday, and at 7.40 pm on Sunday. FIVE DOLLARS A TICKET AT THE DOOR Giasone was irst performed at the Teatro San Cassiano in Venice FIVE PM MONDAY TO FRIDAY on 5 January 1649. Giasone is being recorded live for CD release on the Pinchgut LIVE label, and is being broadcast on ABC Classic FM on Sunday 8 December at 7 pm. Any microphones you observe are for recording and not ampliication. -

Accessible Opera: Overcoming Linguistic and Sensorial Barriers

This is a post-print version of the following article: Orero, Pilar; Matamala, Anna (2007) Accessible Opera: Overcoming Linguistic and Sensorial Barriers. Perspectives. Studies in Translatology, 15(4): 427-451. DOI: 10.1080/13670050802326766 http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13670050802326766#.U0afL-Z_sWU Accessible Opera: Overcoming Linguistic and Sensorial Barriers The desire to make media available for all has been rapidly accepted and implemented by most European countries. Opera, as one of the many audiovisual representations, also falls under the category of production which needs to be made accessible and this article aims to analyse how opera has gone through a complete transformation to become a cultural event for all, overcoming not only linguistic but also sensorial barriers. The first part of the article analyses the various forms of translation associated with opera and the main challenges they entail. The second presents different systems used to make opera accessible to the sensorially challenged, highlighting their main difficulties. Examples from research carried out at the Barcelona’s Liceu opera house are presented to illustrate various modalities, especially audio description. All in all, it is our aim to show how translated-related processes have made it possible to open opera to a wider audience despite some initial reluctance. 1. Overcoming linguistic barriers Performing opera in the source language or in the language of the audience has been a major discussion in the literature of Translation Studies —and references are found from as distant fields as Music Studies and as early as the beginning of the 20th century (Spaeth 1915), but it is Nisato (1999:26) who provides a comprehensive summary of the current three possibilities in opera performance, which in our opinion can perfectly coexist: “performing the opera in its original language and provide the listener with either a synopsis or translated libretto, to perform in the original language and make use of surtitles, or to perform a sung translation of the work”. -

John Conklin • Speight Jenkins • Risë Stevens • Robert Ward John Conklin John Conklin Speight Jenkins Speight Jenkins Risë Stevens Risë Stevens

2011 NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS 1100 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20506-0001 John Conklin • Speight Jenkins • Risë Stevens • Robert Ward John Conklin John Conklin Speight Jenkins Speight Jenkins Risë Stevens Risë Stevens Robert Ward Robert Ward NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS 2011 John Conklin’s set design sketch for San Francisco Opera’s production of The Ring Cycle. Image courtesy of John Conklin ii 2011 NEA OPERA HONORS Contents 1 Welcome from the NEA Chairman 2 Greetings from NEA Director of Music and Opera 3 Greetings from OPERA America President/CEO 4 Opera in America by Patrick J. Smith 2011 NEA OPERA HONORS RECIPIENTS 12 John Conklin Scenic and Costume Designer 16 Speight Jenkins General Director 20 Risë Stevens Mezzo-soprano 24 Robert Ward Composer PREVIOUS NEA OPERA HONORS RECIPIENTS 2010 30 Martina Arroyo Soprano 32 David DiChiera General Director 34 Philip Glass Composer 36 Eve Queler Music Director 2009 38 John Adams Composer 40 Frank Corsaro Stage Director/Librettist 42 Marilyn Horne Mezzo-soprano 44 Lotfi Mansouri General Director 46 Julius Rudel Conductor 2008 48 Carlisle Floyd Composer/Librettist 50 Richard Gaddes General Director 52 James Levine Music Director/Conductor 54 Leontyne Price Soprano 56 NEA Support of Opera 59 Acknowledgments 60 Credits 2011 NEA OPERA HONORS iii iv 2011 NEA OPERA HONORS Welcome from the NEA Chairman ot long ago, opera was considered American opera exists thanks in no to reside within an ivory tower, the small part to this year’s honorees, each of mainstay of those with European whom has made the art form accessible to N tastes and a sizable bankroll. -

Robert Penn Warren: a Documentary Volume Contents

Dictionary of Literary Biography • Volume Three Hundred Twenty Robert Penn Warren: A Documentary Volume Contents Plan of the Series xxiii Introduction xxv Acknowledgments xxviii Permissions xxx Works by Robert Penn Warren 3 Chronology 8 Launching a Career: 1905-1933 20 Kentucky Beginnings 20 Facsimile: Pages from the Warren family Bible An Old-Time Childhood—from Warren's poem "Old-Time Childhood in Kentucky" The Author and the Ballplayer-from Will Fridy, "The Author and the Ballplayer: An Imprint of Memory in the Writings of Robert Penn Warren" Early Reading-from Ralph Ellison and Eugene Walter, "The Art of Fiction XVIII: Robert Penn Warren" Clarksville High School. '. -. J , 30 Facsimile: Warren's essay on his first day at Clarksville High School Facsimile: First page of "Munk" in The Purple and Gold, February 1921 Facsimile: "Senior Creed" in The Purple and Gold, April 1921 Writing for The Purple and Gold—from Tom Wibking, "Star's Work Seasoned by Country Living" Becoming a Fugitive 38 "Incidental and Essential": Warren's Vanderbilt Experience-from "Robert Penn Warren: A Reminiscence" A First Published Poem-"Prophecy," The Mess Kit (Foodfor Thought) and Warren letter - to Donald M. Kington, 6 March 1975 The Importance of The Fugitive—horn Louise Cowan, The Fugitive Group: A Literary History Brooks and Warren at Vanderbilt-from Cleanth Brooks, "Brooks on Warren" A Fugitive Anthology-Warren letter to Donald Davidson, 19 September 1926 Katherine Anne Porter Remembers Warren—from Joan Givner, Katherine Ann Porter: A Life A Literary Bird Nest—from Brooks, "A Summing Up" The Fugitives as a Group-from Ellison and Walter, "The Art of Fiction XVIII: Robert Penn Warren" Facsimile: Page from a draft of John Brown A Glimpse into the Warren Family 52 Letters from Home: Filial Guilt in Robert Penn Warren-from an essay by William Bedford Clark xiii Contents DLB 320 Warren and Brooks at Oxford-from Brooks, "Brooks on Warren" Facsimile: Warren postcard to his mother, April 1929 A First Book -. -

August 2016 List

August 2016 Catalogue Prices valid until Wednesday 28�� September 2016 unless stated otherwise 0115 982 7500 [email protected] 1 Welcome! Dear Customer, The ‘Shakespeare 400’ celebrations have been in full swing for a few months now, with performances and special events happening around the UK and beyond. Here at Europadisc, we have seen an uplift of interest in the DVD/Blu- ray versions of his plays recorded at the RSC and The Globe Theatre (issued by Opus Arte), and there have been a noticeable number of Shakespeare-themed recitals on CD featuring items such musical settings of the sonnets. Although our focus is primarily on classical music, we have agreed to feature a new CD set issued by Decca this month containing the complete plays, sonnets and poems of Shakespeare recorded by The Marlowe Dramatic Society back in the ‘50s and ‘60s, originally released on Argo Records. It is a beautifully presented boxset containing 100 CDs alongside a 200pp booklet crammed with fascinating notes and historical information. Much more information can be found on p.4 - highly recommended! Other boxsets featured this month include the Complete Remastered Stereo Collection of recordings from Jascha Heifetz on Sony (RCA), the Complete Decca Recordings of pianist Julius Katchen and some bargain re-issues of wonderful recordings from EMI, Virgin, Warner and Erato in Warner Classics’ Budget Boxset range. Of course, we mustn’t forget the many interesting new recordings being released: highlights include the next discs in both the Classical Piano Concerto (FX Mozart/Clementi) and the Romantic Violin Concerto (Stojowski/Wieniawski) series on Hyperion (p.5); four brand new titles from Dutton Epoch (see opposite); the already well-reviewed final instalment in Osmo Vänskä’s latest Sibelius cycle on BIS (Disc of the Month - see below); and a brilliant performance of works by Telemann from Florilegium (p.8). -

'It Could Have Been Different': Value and Meaning in Carlisle Floyd's

‘It Could Have Been Different’: Value and Meaning in Carlisle Floyd’s Willie Stark Patricia Sasser University Libraries University of South Carolina Carlisle Floyd • Born in 1926 in Latta, South Carolina • Educated first at Converse College, then at Syracuse University • Studied with Ernst Bacon • Taught at Florida State University The South Carolina Railroad Photograph Collection http://digital.tcl.sc.edu/u?/rrc,1580 Floyd’s operas Early works • Slow Dusk (1949) • The Fugitives (1951) • Susannah (1955) New England Conservatory Flickr stream (http://www.flickr.com/photos/27770344@N02/2843094973/) Floyd’s operas Original libretti by Floyd Libretti adapted by Floyd • The Passion of Jonathan • Wuthering Heights (1958) Wade (1962) • Markheim (1966) • The Sojourner and Mollie • Of Mice and Men (1970) Sinclair (1963) • Bilby’s Doll (1976) • Flower and Hawk (1972) • Willie Stark (1981) • Cold Sassy Tree (2000) All the King’s Men Characters • Jack Burden • Burden family • Adam Stanton and Anne Stanton • Stanton family • Willie Stark • Stark family • Cass Mastern • Judge Irwin • Sugar Boy • Sadie Burke Broderick Crawford as Willie Stark in Columbia Pictures ‘ 1949 film of All the King’s Men cooperscooperday Flickr stream: http://www.flickr.com/photos/39665917@N02/4007146067/ “Even to an unmusical barbarian like me your fame has penetrated, and so the introduction by Paul, and by your extremely interesting enclosures, was scarcely necessary. I’d be honored to have you do All the King’s Men, as you can well imagine.” - Robert Penn Warren to Carlisle -

SOME AMERICAN OPERAS/COMPOSERS October 2014

SOME AMERICAN OPERAS/COMPOSERS October 2014 Mark Adamo-- Little Women, Lysistrata John Adams—Nixon in China, Death of Klinghoffer, Doctor Atomic Dominick Argento—Postcard From Morocco, The Aspern Papers William Balcom—A View From the Bridge, McTeague Samuel Barber—Antony and Cleopatra, Vanessa Leonard Bernstein— A Quiet Place, Trouble in Tahiti Mark Blitzstein—Regina, Sacco and Venzetti, The Cradle Will Rock David Carlson—Anna Karenina Aaron Copland—The Tender Land John Corigliano—The Ghosts of Versailles Walter Damrosch—Cyrano, The Scarlet Letter Carlisle Floyd—Susannah, Of Mice and Men, Willie Stark, Cold Sassy Tree Lukas Foss—Introductions and Goodbyes George Gershwin—Porgy and Bess Philip Glass—Satyagraha, The Voyage, Einstein on the Beach, Akhnaten Ricky Ian Gordon—Grapes of Wrath Louis Gruenberg—The Emperor Jones Howard Hanson—Merry Mount John Harbison—The Great Gatsby, Winter’s Tale Jake Heggie—Moby Dick, Dead Man Walking Bernard Hermann—Wuthering Heights Jennifer Higdon—Cold Mountain (World Premiere, Santa Fe Opera, 2015) Scott Joplin—Treemonisha Gian Carlo Menotti—The Consul, The Telephone, Amahl and the Night Visitors Douglas Moore—Ballad of Baby Doe, The Devil and Daniel Webster, Carrie Nation Stephen Paulus—The Postman Always Rings Twice, The Woodlanders Tobias Picker—An American Tragedy, Emmeline, Therese Racquin Andre Previn—A Streetcar Named Desire Ned Rorem—Our Town Deems Taylor—Peter Ibbetson Terry Teachout—The Letter Virgil Thompson—Four Saints in Three Acts, The Mother of Us All Stewart Wallace—Harvey Milk Kurt Weill—Street Scene, Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny .