Cut with the Kitchen Knife: the Berlin Dada Photomontages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Text and the Coming of Age of the Avant-Garde in Germany

The Text and the Coming of Age of the Avant-Garde in Germany Timothy 0. Benson Visible Language XXI 3/4 365-411 The radical change in the appearance of the text which oc © 1988 Visible Language curred in German artists' publications during the teens c/o Rhode Island School of Design demonstrates a coming of age of the avant-garde, a transfor Providence, RI 02903 mation in the way the avant-garde viewed itself and its role Timothy 0. Benson within the broader culture. Traditionally, the instrumental Robert Gore Riskind Center for purpose of the text had been to interpret an "aesthetic" ac German Expressionist Studies tivity and convey the historical intentions and meaning as Los Angeles County Museum ofArt sociated with that activity. The prerogative of artists as 5905 Wilshire Boulevard well as critics, apologists and historians, the text attempted Los Angeles, CA 90036 to reach an observer believed to be "situated" in a shared web of events, thus enacting the historicist myth based on the rationalist notion of causality which underlies the avant garde. By the onset of the twentieth century, however, both the rationalist basis and the utopian telos generally as sumed in the historicist myth were being increasingly chal lenged in the metaphors of a declining civilization, a dis solving self, and a disintegrating cosmos so much a part of the cultural pessimism of the symbolist era of "deca dence."1 By the mid-teens, many of the Expressionists had gone beyond the theme of an apocalypse to posit a catastro phe so deep as to void the whole notion of progressive so cial change.2 The aesthetic realm, as an arena of pure form and structure rather than material and temporal causality, became more than a natural haven for those artists and writers who persisted in yearning for such ideals as Total itiit; that sense of wholeness for the individual and human- 365 VISIBLE LANGUAGE XXI NUMBER 3/4 1987 *65. -

Images of the Worker in John Heartfield's Pro-Soviet Photomontages a Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School A

Images of the Worker in John Heartfield’s Pro-Soviet Photomontages A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by DANA SZCZECINA Dr. James van Dyke, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2020 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled IMAGES OF THE WORKER IN JOHN HEARTFIELD’S PRO=SOVIET PHOTOMONTAGES Presented by Dana Szczecina, a candidate for the degree of master of the arts , and hereby certify that in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor James van Dyke Professor Seth Howes Professor Anne Stanton ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am deeply grateful for the guidance and support of my thesis adviser Dr. van Dyke, without whom I could not have completed this project. I am also indebted to Dr, Seth Howes and Dr. Anne Stanton, the other two members of my thesis committee who provided me with much needed and valuable feedback. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………………ii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS……………………………………………………………………………….iv ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………………..vii Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter One……………………………………………………………………………………………...11 Chapter Two……………………………………………………………………………………………25 Chapter Three……………………………………………………………………………………………45 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………...68 BIBLIOGRAPHY……………………………………………………………………………….71 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Film und Foto, Installation shot, Room 3, 1929. Photograph by Arthur Ohler. (Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Archiv Bildende Kunst.)…………………………….1 2. John Heartfield, Five Fingers Has the Hand, 1928 (Art Institute Chicago)…………………………………………………………………..1 3. John Heartfield, Little German Christmas Tree, 1934 (Akademie der Künste)…………………………………………………………………3 4. Gustav Klutsis, All Men and Women Workers: To the Election of the Soviets, 1930 (Art Institute Chicago)……………………………………………………………6 5. -

Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada Studies in the Fine Arts: the Avant-Garde, No

NUNC COCNOSCO EX PARTE THOMAS J BATA LIBRARY TRENT UNIVERSITY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2019 with funding from Kahle/Austin Foundation https://archive.org/details/raoulhausmannberOOOObens Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada Studies in the Fine Arts: The Avant-Garde, No. 55 Stephen C. Foster, Series Editor Associate Professor of Art History University of Iowa Other Titles in This Series No. 47 Artwords: Discourse on the 60s and 70s Jeanne Siegel No. 48 Dadaj Dimensions Stephen C. Foster, ed. No. 49 Arthur Dove: Nature as Symbol Sherrye Cohn No. 50 The New Generation and Artistic Modernism in the Ukraine Myroslava M. Mudrak No. 51 Gypsies and Other Bohemians: The Myth of the Artist in Nineteenth- Century France Marilyn R. Brown No. 52 Emil Nolde and German Expressionism: A Prophet in His Own Land William S. Bradley No. 53 The Skyscraper in American Art, 1890-1931 Merrill Schleier No. 54 Andy Warhol’s Art and Films Patrick S. Smith Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada by Timothy O. Benson T TA /f T Research U'lVlT Press Ann Arbor, Michigan \ u » V-*** \ C\ Xv»;s 7 ; Copyright © 1987, 1986 Timothy O. Benson All rights reserved Produced and distributed by UMI Research Press an imprint of University Microfilms, Inc. Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Benson, Timothy O., 1950- Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada. (Studies in the fine arts. The Avant-garde ; no. 55) Revision of author’s thesis (Ph D.)— University of Iowa, 1985. Bibliography: p. Includes index. I. Hausmann, Raoul, 1886-1971—Aesthetics. 2. Hausmann, Raoul, 1886-1971—Political and social views. -

Cat144 Sawyer.Qxd

D aDA & c O . ars libri ltd catalogue 144 142 CAT ALOGUE 144 D aDA & cO. ars libri ltd ARS LIBRI LTD 500 Harrison Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02118 U.S.A. tel: 617.357.5212 fax: 617.338.5763 email: [email protected] http://www.arslibri.com All items are in good antiquarian condition, unless otherwise described. All prices are net. Massachusetts residents should add 5% sales tax. Reserved items will be held for two weeks pending receipt of payment or formal orders. Orders from individuals unknown to us must be accompanied by pay - ment or by satisfactory references. All items may be returned, if returned within two weeks in the same condition as sent, and if packed, shipped and insured as received. When ordering from this catalogue please refer to Catalogue Number One Hundred and Forty-Four and indicate the item number(s). Overseas clients must remit in U.S. dollar funds, payable on a U.S. bank, or transfer the amount due directly to the account of Ars Libri Ltd., Cambridge Trust Company, 1336 Massachusetts Avenue, Cam- bridge, MA 02238, Account No. 39-665-6-01. Mastercard, Visa and American Express accepted. May 2008 n avant-garde 5 1 ABE KONGO Shururearizumu kaigaron [Surrealist Painting]. 115, (5)pp., 10 plates (reproducing work by Ozenfant, Picabia, Léger, Bran- cusi, Ernst, and others). Printed wraps. Glassine d.j. Back- strip chipped, otherwise fine. Tokyo (Tenjinsha), 1930. $1,200.00 Centre Georges Pompidou: Japon des avant-gardes 1910/1970 (Paris, 1986), pp. 192 (illus.), 515 2 ABE KONGO Abe Kongo gashu [Paintings by Abe Kongo]. -

Dadaistische Fotografie: Zur Kunst Der Fotomontage Bachelorseminar Herbstsemester 2014, Teilgebiet C (Moderne), 9 ECTS-Punkte Leitung: Nicole A

Kunsthistorisches Institut, Universität Zürich Lehrstuhl Geschichte der bildenden Kunst, Prof. Dr. Bettina Gockel: http://www.khist.uzh.ch/chairs/bildende/lehre.html Dadaistische Fotografie: Zur Kunst der Fotomontage Bachelorseminar Herbstsemester 2014, Teilgebiet C (Moderne), 9 ECTS-Punkte Leitung: Nicole A. Krup, M.A. ([email protected]) Mi. 14-15:45 Uhr; Sprechstunde in der Regel nach der Sitzung Sprache: Englisch und Deutsch „Die Dadaisten anerkennen als einziges Programm die Pflicht, zeitlich und örtlich das gegenwärtige Geschehen zum Inhalt ihrer Bilder zu machen, weswegen sie auch nicht Tausend und eine Nacht oder Bilder aus Hinterindien, sondern die illustrierte Zeitung und die Leitartikel der Presse als Quell ihrer Produktion ansehen. „Betrachten wir uns unter diesen Gesichtspunkten einige Bilder.“ - Wieland Herzfelde Aus „Zur Einführung.“ Katalog der Ersten Internationalen Dada-Messe. Kunsthandlung R. Otto burchard. Der Malik-Verlag, Abteilung Dada. Berlin, Juni 1920. Auch wenn die Dadaisten kein „einziges Programm“ hatten, stand die Fotografie, vornehmlich als Reproduktionen in den Massenmedien, als Material erster Wahl in ihrer „Produktion“. Im Rahmen dieses Bachelorseminars werden wir diesen Aufruf von Wieland Herzfelde als kritische BetrachterInnen dieses besonderen Bereiches der dadaistischen Produktion – der bald darauf nach 1920 eine Apotheose unter dem Namen „Fotomontage“ erreichte – von Berlin über den Bauhaus hinaus bis jenseits von Dada und in die Zwischenkriegszeit in Europa nach Amerika folgen, um ein Verständnis des breiten Spektrums der Ansätze zur Fotografie als schöpferische Materialien zu erlangen. Neben dem Bildmaterial stehen zudem Manifeste, Aufsätze wie die von Herzfelde und Gedichte sowie Erinnerungen und Schriften von Fotomonteuren und seinen Betrachtern im Fokus, um eine historische Kontextualisierung und Problematisierung der Ziele der Fotomontage zu ermöglichen. -

East German Intellectuals and Public Discourses in the 1950S

East German Intellectuals and Public Discourses in the 1950s Wieland Herzfelde, Erich Loest and Peter Hacks Hidde van der Wall, MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2013 1 To the memory of my parents 2 Table of Contents Abstract 5 Publications arising from this thesis 6 Acknowledgements 7 1. Introduction 9 1. Selection of authors and source material 10 2. The contested memory of the GDR 13 3. Debating the role of intellectuals in the GDR 21 4. The 1950s: debates, events, stages 37 5. The generational paradigm 53 2. Wieland Herzfelde: Reforming Party discourses from within 62 1. Introduction 62 2. Ambiguous communist involvement before 1949 67 3. Return to an antifascist homeland 72 4. Aesthetics: Defending a legacy 78 5. Affirmative stances in the lectures 97 6. The June 1953 uprising 102 7. German Division and the Cold War 107 8. The contexts of criticism in 1956-1957 126 9. Conclusion 138 3 3. Erich Loest: Dissidence and conformity 140 1. Introduction 140 2. Aesthetics: Entertainment, positive heroes, factography 146 3. Narrative fiction 157 4. Consensus and dissent: 1953 183 5. War stories 204 6. Political opposition 216 7. Conclusion 219 4. Peter Hacks: Political aesthetics 222 1. Introduction 222 2. Political affirmation 230 3. Aesthetics: A programme for a socialist theatre 250 4. Intervening in the debate on didactic theatre 270 5. Two ‗dialectical‘ plays 291 6. Conclusion 298 5. Conclusion 301 Bibliography 313 4 Abstract The aim of this thesis is to contribute to a differentiated reassessment of the cultural history of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), which has hitherto been hampered by critical approaches which have the objective of denouncing rather than understanding East German culture and society. -

John Heartfield: Wallpapering the Everyday Life of Leftist

the art institute of chicago yale university press, new haven and london edited by matthew s. witkovsky Avant-Garde Art Avant-Garde Life in Everyday with essays by jared ash, maria gough, jindŘich toman, nancy j. troy, matthew s. witkovsky, early-twentieth-century european modernism early-twentieth-century and andrés mario zervigÓn contents 8 Foreword 10 Acknowledgments 13 Introduction matthew s. witkovsky 29 1. John Heartfield andrés mario zervigÓn 45 2. Gustav Klutsis jared ash 67 3. El Lissitzky maria gough 85 4. Ladislav Sutnar jindŘich toman 99 5. Karel Teige matthew s. witkovsky 117 6. Piet Zwart nancy j. troy 137 Note to the Reader 138 Exhibition Checklist 153 Selected Bibliography 156 Index 160 Photography Credits 29 john heartfield 1 John Heartfield wallpapering the everyday life of leftist germany andrés mario zervigón 30 john heartfield In Germany’s turbulent Weimar Republic, political orientation defined the daily life of average communists and their fellow travelers. Along each step of this quotidian but “revolutionary” existence, the imagery of John Heartfield offered direction. The radical- left citizen, for instance, might rise from bed and begin his or her morning by perusing the ultra- partisan Die rote Fahne (The Red Banner); at one time, Heartfield’s photomontages regularly appeared in this daily newspaper of the German Communist Party (KPD).1 Opening the folded paper to its full length on May 13, 1928, waking communists would have been confronted by the artist’s unequivocal appeal to vote the party’s electoral list. Later in the day, on the way to a KPD- affiliated food cooperative, these citizens would see the identical composition — 5 Finger hat die Hand (The Hand Has Five Fingers) (plate 13) — catapulting from posters plastered throughout urban areas. -

Documenting Dada / Disseminating Dada Da Object List Da Da Da 1

DOCUMENTING DADA / DISSEMINATING DADA DA OBJECT LIST DA DA DA 1. Cabaret Voltaire. Edited by Hugo Ball. Zurich, 1916. 2. Dada no. 1. Edited by Tristan Tzara. Zurich, July 1917. 3. Dada no. 2. Edited by Tristan Tzara. Zurich, December 1917. 4. Dada no. 3 (international edition). Edited by Tristan Tzara. Zurich, December 1918. 5. Dada no. 4 / 5 (Anthologie Dada) (international edition). Edited by Tristan Tzara. Zurich, May 1919. 6. Dada no. 4 / 5 (Anthologie Dada) (French edition). Edited by Tristan Tzara. Zurich, May 1919. 7. La Première Aventure céléste de Mr. Antipyrine. By Tristan Tzara; illustrated by Marcel Janco. Zurich, 1916. 8. Vingt-cinq Poèmes. By Tristan Tzara; illustrated by Hans Arp. Zurich, 1918. 9. 391 no. 8. Edited by Francis Picabia. Zurich, February 1919. 10. 291 no. 2. Edited by Marius de Zayas, Agnes Meyer, Paul Haviland, and Alfred Stieglitz. New York, April 1915. 11. The Blind Man no. 2. Edited by Henri-Pierre Roché, Beatrice Wood, and Marcel Duchamp. New York, May 1917. 12. 391 no. 7. Edited by Francis Picabia. New York, August 1917. 13. 391 no. 14. Edited by Francis Picabia. Paris, November 1920. 14. Excursions et visites Dada. Paris, 1921. 15. Une Bonne Nouvelle. (Invitation to opening of Exposition Dada Man Ray). Paris, 1921. 16. Exposition Dada Max Ernst. Paris, 1921. 17. [Papillon Dada: “Chaque spectateur est un intrigant”]. Zurich, 1919. 18. [Papillon Dada: “Dada: Société Anonyme pour l’exploitation du vocabulaire”]. Zurich, 1919. 19. Exposition Dada Francis Picabia. Paris, 1920. 20. Exposition Dada Georges Ribemont Dessaignes. Paris, 1920. 21. Exposition Dada Man Ray. -

Introduction to the First International Dada Fair*

Introduction to the First International Dada Fair* WIELAND HERZFELDE Translated and introduced by Brigid Doherty Printed in red-and-black typography over a photolithographic reproduction of John Heartfield’s montage Life and Activity in Universal City at 12:05 in the Afternoon, the newspaper-sized cover page of the catalog to the First International Dada Fair—an “exhibition and sale” of roughly two hundred “Dadaist products” that was held from June 30 to August 25, 1920, in a Berlin art gallery owned by Dr. Otto Burchard, an expert in Song period Chinese ceramics who underwrote the show with an investment of one thousand marks and thereby earned the title “Financedada”—asserts that “the Dada movement leads to the sublation of the art trade.”1 Aufhebung is the Dadaists’ word for what their movement does to the traffic in art, and the cover page evokes the trebled meaning that can be attached to that term: the Dada Fair “maintained” the art trade to the extent that it put Dadaist products on the market; at the same time, and indeed thereby, the exhibition aimed to generate within the walls of a well-situated Berlin art gallery an affront to public taste that would “eradicate” the market into which its products were launched, as if, again thereby, to “elevate” the enterprise of dealing in works of art in the first place. Organized by George Grosz, who is given the military rank “Marshall” on the cover page, Raoul Hausmann, “Dadasopher,” and Heartfield, “Monteurdada,” the Dada Fair failed as a commercial venture. Despite charging a considerable admission fee of three marks thirty (a sum even higher than the cat- alog announces), while asking an additional one mark seventy for the catalog, which was published three weeks into the run of the show, the Dadaists could not bring in enough from sales to turn a profit. -

Addressing the Viewer: the Use of Text in the First International Dada Fair

Addressing the Viewer: The Use of Text in the First International Dada Fair Megan Kosinski Honors Thesis School of Art + Art History April 6, 2012 Kosinski 2 Focused on the group carefully posed in the center of the image, the most popular photograph (Figure 1) of the First International Dada Fair captured members of Club Dada viewing their own creations. Hannah Höch, seated on the left bench, looks out just beyond the camera, modeling the most fashionable Bubikopf hair style and modern dress. Directly in front of her, yet not in line with her gaze, hangs Otto Dix’s 45% Ablebodied (also known as War Cripples), topped with two printed posters, one which reads “Take / DADA seriously, / it’s worth it!”1 Behind her, Dr. Otto Burchard, Raoul Hausmann, and Johannes Baader stand together in front of Grosz’s Victim of Society (Remember Uncle August, the Unhappy Inventor) in a seemingly intense conversation with one another. Like Höch, these three gentlemen showcase modern men’s Weimar fashions. In the doorway, surrounded by five printed posters, one clearly stating “Dabblers / rise yourselves / against art!” stand Mr. and Mrs. Wieland Herzfelde who both look at the works displayed on the wall.2 While Mr. Herzfelde wears a Figure 1 Installation view of the First International Dada Fair look of interest, Mrs. Herzfelde appears confused and (Altshulter, “DADA ist politisch,” 100.) bewildered at the art presented to her. The back wall, not viewed by any of the figures in the picture, displays Grosz’s large Germany, a Winter’s Tale, buttressed underneath with a poster stating “DADA is/ political”.3 Otto Schmalhausen sits on a chair looking off the right edge of the photograph, his gaze complemented by George Grosz and John Heartfield, and looks towards Grosz and Heartfield’s The Philistine Heartfield Gone Wild (Electo-Mechanical Tatlin Plastic). -

Max Ernst Wird Am 2

Max Ernst GALERIE HENZE & KETTERER & TRIEBOLD Wettsteinstrasse 4 – CH 4125 Riehen/Basel Tel. +41/61/641 77 77 Fax:+41/61/641 77 78 www.henze-ketterer.ch – [email protected] BIOGRAPHIE BIOGRAPHY Max Ernst wird am 2. April 1891 in Brühl, Deutschland, geboren. Max Ernst was born on 2 April 1891 in Brühl, Germany. 1909 immatrikuliert Max Ernst sich an der Universität Bonn, um Philosophie zu studieren, gibt dieses Studium aber bald wieder auf, um sich der Kunst zu widmen. In 1909 Max Ernst enrolles in the University at Bonn to study philosophy, but soon abandoned this to concentrate on art. 1911 lernt Max Ernst August Macke kennen, daraus entwickelt sich eine enge Freundschaft. Im selben Jahr schliesst sich Ernst der Gruppe der Rheinischen Expressionisten in Bonn an. In 1911 Max Ernst meets August Macke, who becomes a close friend of Max Ernst. In the same year Ernst joins the group of the Rheinische Expressionisten in Bonn. MAX ERNST IM BRÜHLER SCHLOSSPARK, 1909. MAX ERNST IN THE CASTLE PARK IN BRÜHL IN 1909. 1913 lernt Guillaume Apollinaire und Robert Delaunay kennen, reist nach Paris, nimmt dort am Ersten deutschen Herbstsalon in Paris teil. In 1913 he meets Guillaume Apollinaire and Robert Delaunay, travel to Paris, Ernst participates in the Erster deutscher Herbstsalon. 1914 lernt er Jean Arp kennen, der sein lebenslanger Freund wird. Im selben Jahr meldet sich Max Ernst freiwillig zum Militärdienst. Er ist trotz des Dienstes weiter künstlerisch tätig. In 1914 he meets Jean Arp, who become his lifelong friend. In the same year Max Ernst volunteers for military service. -

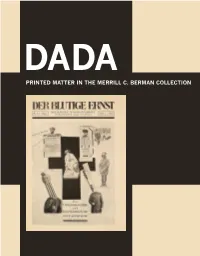

Dada: Printed Matter in the Merrill C. Berman Collection

DADA DADA PRINTED MATTER IN THE MERRILL C. BERMAN COLLECTION PRINTED MATTE RIN THE MERRILL C. BERMAN COLLECTION BERMAN C. MERRILL THE RIN MATTE PRINTED © 2018 Merrill C. Berman Collection © 2018 AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F © T O H C E 2018 M N A E R M R R I E L L B . C DADA PRINTED MATTER IN THE MERRILL C. BERMAN COLLECTION Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and notes by Adrian Sudhalter Design and production by Jolie Simpson Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Images © 2018 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2018 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Der Blutige Ernst, year 1, no. 6 ([1920]) Issue editor: Carl Einstein Cover: George Grosz Letterpress on paper 12 1/2 x 9 1/2” (32 x 24 cm) CONTENTS 7 Headnote 10 1917 14 1918 18 1919 24 1920 48 1921 72 1922 78 1923 90 1924 96 1928 JOURNALS 104 1915-1916 291 126 1917 Neue Jugend 128 1917 The Blind Man 130 1917-1920 Dada 132 1917-1924 391 140 1918 Die Freie Strasse 146 1919 Jedermann sein eigener Fussball 148 1919-1920 Der Dada 152 1919-1924 Die Pleite 162 1919-1920 Der Blutige Ernst 168 1919-1920 Dada Quatsch 172 1920 Harakiri 176 1922-1923 Mécano 182 1922-1928 Manométre 184 1922 La Pomme de Pins 186 1922 La Coeur à Barbe 190 1923-1932 Merz Headnote Adrian Sudhalter Synthetic studies of Dada from the 1930s until today have tended to rely on a city-based cities was a point of pride among the Dadaists themselves: each new locale functioning as an outpost within Dada’s international network (see, for example, Tzara’s famous letterhead on p.