Economic Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tunisia Summary Strategic Environmental and Social

PMIR Summary Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT: ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE MODERNIZATION PROJECT COUNTRY: TUNISIA SUMMARY STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT (SESA) Project Team: Mr. P. M. FALL, Transport Engineer, OITC.2 Mr. N. SAMB, Consultant Socio-Economist, OITC.2 Mr. A. KIES, Consultant Economist, OITC 2 Mr. M. KINANE, Principal Environmentalist, ONEC.3 Mr. S. BAIOD, Consultant Environmentalist ONEC.3 Project Team Sector Director: Mr. Amadou OUMAROU Regional Director: Mr. Jacob KOLSTER Division Manager: Mr. Abayomi BABALOLA 1 PMIR Summary Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment Project Name : ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE MODERNIZATION PROJECT Country : TUNISIA Project Number : P-TN-DB0-013 Department : OITC Division: OITC.2 1 Introduction This report is a summary of the Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment (SESA) of the Road Project Modernization Project 1 for improvement works in terms of upgrading and construction of road structures and primary roads of the Tunisian classified road network. This summary has been prepared in compliance with the procedures and operational policies of the African Development Bank through its Integrated Safeguards System (ISS) for Category 1 projects. The project description and rationale are first presented, followed by the legal and institutional framework in the Republic of Tunisia. A brief description of the main environmental conditions is presented, and then the road programme components are presented by their typology and by Governorate. The summary is based on the projected activities and information contained in the 60 EIAs already prepared. It identifies the key issues relating to significant impacts and the types of measures to mitigate them. It is consistent with the Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) developed to that end. -

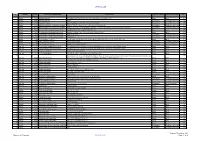

December 2020 Contract Pipeline

OFFICIAL USE No Country DTM Project title and Portfolio Contract title Type of contract Procurement method Year Number 1 2021 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways SupervisionRehabilitation Contract of Tirana-Durres for Rehabilitation line and ofconstruction the Durres of- Tirana a new Railwaylink to TIA Line and construction of a New Railway Line to Tirana International Works Open 2 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Airport Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 3 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Asset Management Plan and Track Access Charges Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 4 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Albania: Tourism-led Model For Local Economic Development Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 5 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Infrastructure and Tourism Enabling Programme: Gender and Economic Inclusion Programme Manager Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 6 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Rehabilitation of Vlore - Orikum Road (10.6 km) Works Open 2022 7 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Upgrade of Zgosth - Ura e Cerenecit road Section (47.1km) Works Open 2022 8 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Works supervision Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 9 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity PIU support Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 10 Albania 51908 Kesh Floating PV Project Design, build and operation of the floating photovoltaic plant located on Vau i Dejës HPP Lake Works Open 2021 11 Albania 51908 -

S.No Governorate Cities 1 L'ariana Ariana 2 L'ariana Ettadhamen-Mnihla 3 L'ariana Kalâat El-Andalous 4 L'ariana Raoued 5 L'aria

S.No Governorate Cities 1 l'Ariana Ariana 2 l'Ariana Ettadhamen-Mnihla 3 l'Ariana Kalâat el-Andalous 4 l'Ariana Raoued 5 l'Ariana Sidi Thabet 6 l'Ariana La Soukra 7 Béja Béja 8 Béja El Maâgoula 9 Béja Goubellat 10 Béja Medjez el-Bab 11 Béja Nefza 12 Béja Téboursouk 13 Béja Testour 14 Béja Zahret Mediou 15 Ben Arous Ben Arous 16 Ben Arous Bou Mhel el-Bassatine 17 Ben Arous El Mourouj 18 Ben Arous Ezzahra 19 Ben Arous Hammam Chott 20 Ben Arous Hammam Lif 21 Ben Arous Khalidia 22 Ben Arous Mégrine 23 Ben Arous Mohamedia-Fouchana 24 Ben Arous Mornag 25 Ben Arous Radès 26 Bizerte Aousja 27 Bizerte Bizerte 28 Bizerte El Alia 29 Bizerte Ghar El Melh 30 Bizerte Mateur 31 Bizerte Menzel Bourguiba 32 Bizerte Menzel Jemil 33 Bizerte Menzel Abderrahmane 34 Bizerte Metline 35 Bizerte Raf Raf 36 Bizerte Ras Jebel 37 Bizerte Sejenane 38 Bizerte Tinja 39 Bizerte Saounin 40 Bizerte Cap Zebib 41 Bizerte Beni Ata 42 Gabès Chenini Nahal 43 Gabès El Hamma 44 Gabès Gabès 45 Gabès Ghannouch 46 Gabès Mareth www.downloadexcelfiles.com 47 Gabès Matmata 48 Gabès Métouia 49 Gabès Nouvelle Matmata 50 Gabès Oudhref 51 Gabès Zarat 52 Gafsa El Guettar 53 Gafsa El Ksar 54 Gafsa Gafsa 55 Gafsa Mdhila 56 Gafsa Métlaoui 57 Gafsa Moularès 58 Gafsa Redeyef 59 Gafsa Sened 60 Jendouba Aïn Draham 61 Jendouba Beni M'Tir 62 Jendouba Bou Salem 63 Jendouba Fernana 64 Jendouba Ghardimaou 65 Jendouba Jendouba 66 Jendouba Oued Melliz 67 Jendouba Tabarka 68 Kairouan Aïn Djeloula 69 Kairouan Alaâ 70 Kairouan Bou Hajla 71 Kairouan Chebika 72 Kairouan Echrarda 73 Kairouan Oueslatia 74 Kairouan -

Tunisia 01 April - 30 June 2017

OPERATIONAL UPDATE Tunisia 01 April - 30 June 2017 Tunisia is a country that has In Tunisia, UNHCR’s priorities are Together with Tunisian maintained an open-door policy to support the development of a authorities and its partner to people fleeing conflict and national asylum system and ADRA, UNHCR assists persecutions. build national capacities and to registered urban refugees and protect and assist refugees and asylum seekers to become asylum seekers. self-reliant. FUNDING REQUIREMENT (AS OF 7 AUGUST 2017) Priorities Support Tunisian authorities into establishing a USD 5.8 M requested for Tunisia national asylum system and progressively assuming refugee protection functions; Provide protection and assistance to refugees and asylum seekers in Tunisia and support them to Funded become self-reliant; 12% Build national capacities to prepare and respond to refugee emergencies, in a context of mixed migration. Key figures 68 most vulnerable refugees and asylum-seekers received financial assistance in June 2017. So far in 2017, 27 refugees signed working contracts and 28 benefited from vocational trainings. Gap 177 people were rescued at sea off Tunisian coast 88% so far in 2017. So far, 14 among them have approached UNHCR to claim asylum in Tunisia. POPULATION OF CONCERN TO UNHCR Countries of origin Syria 461 Palestine 31 Sudan 32 Iraq 20 Other nationalities* 82 Others of Concern** 4 TOTAL: 630 (Figures as of 30 June 2017) * Other nationalities (17) ** Others of Concern: specific groups of persons not normally falling under the mandate of UNHCR, but to whom extends protection and/or assistance. www.unhcr.org 1 OPERATIONAL UPDATE > Tunisia / 01 April-30 June 2017 Update On Achievements Operational Context . -

World Bank Document

L S s ~~~~- - . D; u n of The World Bank FOROM-ICI4L USE ONLY 10K.~~~~~~~~~~~ * * ,<t ~a, *;>6 E) ,-L Public Disclosure Authorized ReportNo. Ms-.N Public Disclosure Authorized STAF? APPRAISALREPORT TUNISIA GABESIRRIGATION PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized May 30, 1985 Public Disclosure Authorized Europe, Middle East and North Africa Projects Department l-dsmmuha a resiuidmdiuibe._ md aybe wad byredplet onlyIn thepeifezee d ~~~brsfMdd l-.:- ;.mt ma ow odme be Alsd _ibu W dd Bak CURRENCY E-QUIVALENTS Currency Tuit Tunisian Dinar (D) US$1.00 D 0.75 D 1.00-=US$1.33 WEIGHTSAND MEASURES Metric System GOVERNMENT OF TUNI;IA FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 INITIALS AND ACRONYMS AIC Association of Common Interest (Association d'Interet Collectif) BNDA : National Bank for Agricultural Development (Banque Nationale pour le Developpement Agricole) BNT : National Bank of Tunisia (Banque Nationale de Tunisie) CNEA : National Center of Agricultural Studies (Centre National des Etudes Agricoles) CRGR : Research Center of the Rural Construction Department (Centre de Recherche du Genie Rural) CRDA : Regional Agricultural Development Commission (Commissariat Regional ae Developpement Agricole) CTV : local Extension Unit (Cellule Territoriale de Vulgarisation) DGR : Department of Rural Engineering (Direction du Genie Rural) DGPC : Highway Department of the Ministry of Public Works (Direction CGnerale des Ponts et Chauss6es) DPSAE : Department of Planning, Statistics and Economic Analysis (Direction de la Planification, des Statistiques et des Analyses -

Ieee Icalt'2019

7th IEEE Int. Conf. on Advanced Logistics & Transport June 14-16, 2019 – Marrakech, Morocco IEEE ICALT’2019 Conference Guide http://www.icalt.org/ Technically co-sponsored by: Welcome! Our heartiest welcome to IEEE ICALT 2019, the 7th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Logistics and Transport taking place in Marrakech, Morocco. With this fifth edition, the conference is held for the first time in Morocco after successful editions in Tunisia 2011 and 2013, France 2014, Poland 2016 and Indonesia 2017. The conference aims to bring together researchers and practitioners to discuss issues, challenges and future directions, share their R&D findings and experiences in the following areas: - Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS) - Logistics & Supply Chain Management (LSCM) - Optimization and Logistics Challenges (OLC) - Industrial Engineering (IE) - Logistics 4.0 and Smart Supply Chain (LSSC) We are pleased to announce that we have received 120 submissions. Only 50 papers (41%) were accepted for oral presentations. Accepted papers are characterized by a high scientific quality. Each paper was reviewed by at least three members of the program committee, which consisted of About 140 scientists from 22 countries. Contributions were from 14 different countries: Bulgaria, Algeria, France, Germany, Italy, Turkey, Morocco, Tunisia, United Kingdom, USA, Denmark, United Arab Emirates, and South Korea. The conference has gathered the most outstanding scientists and practitioners in all areas of Logistics, Transport, and their applications. Research in this area comprises a wide spectrum of directions, both theoretical and practical, with a perspective which aims to be useful both to people in the academia and in the industry. The conference reflects all these aspects in detail and offers the possibility of discussing and comparing the latest results obtained by researchers all over the world. -

The Preparatory Survey on Sfax Sea Water Desalination Plant Construction Project in the Republic of Tunisia

MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE, WATER RESOURCES AND FISHERIES SOCIETE NATIONALE D'EXPLOITATION ET DE DISTRIBUTION DES EAUX(SONEDE) THE PREPARATORY SURVEY ON SFAX SEA WATER DESALINATION PLANT CONSTRUCTION PROJECT IN THE REPUBLIC OF TUNISIA FINAL REPORT VOL. 2 : APPENDICES AUGUST 2015 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY NJS CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. INGEROSEC CORPORATION GE JAPAN TECHNO CO., LTD. JR(先) 15-124 MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE, WATER RESOURCES AND FISHERIES SOCIETE NATIONALE D'EXPLOITATION ET DE DISTRIBUTION DES EAUX(SONEDE) THE PREPARATORY SURVEY ON SFAX SEA WATER DESALINATION PLANT CONSTRUCTION PROJECT IN THE REPUBLIC OF TUNISIA FINAL REPORT VOL. 2 : APPENDICES AUGUST 2015 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY NJS CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. INGEROSEC CORPORATION JAPAN TECHNO CO., LTD. TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 2 : APPENDICES CHAPTER 1 PURPOSE AND CONTENTS OF THE SURVEY 1.2- Non-Disclosure Information 1.4-1 Condition of Existing Desalination Plants ------------------------------------------------------ 1.4-1 CHAPTER 2 REVIEW OF EXISTING INFORMATION AND EXPLORATION 2.1-1 Sfax Port ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2.1-1 CHAPTER 4 WATER SUPPLY PLAN FOR GREATER SFAX 4.1-1 Presentation Material for International Donors Conference in Marseille, France---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4.1-1 4.3-1 Existing Water Supply Facilities in Greater Sfax ---------------------------------------------- 4.3-1 CHAPTER 5 STUDY ON SEAWATER DESALINATION PLANT -

WFP Tunisia Country Brief October 2019 Donors Italian Agency for Development Cooperation (AICS)

In Numbers WFP provides capacity-strengthening activities aimed at enhancing the Government-run National School Feeding Programme (NSFP) that reaches 260,000 children (125,000 girls and 135,000 boys) in 2,500 primary schools. The budget for national school feeding doubled in 2019, reaching US$16 million per year, of which US$1.7 million were provided by the Tunisian WFP Tunisia Government for the construction and equipment of a pilot central kitchen and development of a School Food Country Brief Bank. October 2019 Operational Context Operational Updates Tunisia has undergone significant changes since the • On 23 October, WFP hosted an Inter-Agency Contingency Revolution of January 2011. The strategic direction of the Planning (IACP) - Food Security Sector meeting to develop Government of Tunisia currently focuses on strengthening preparedness actions for the potential influx of refugees democracy, while laying the groundwork for a strong and migrants from Libya into southern Tunisia. WFP is the IACP – food security lead. Partners present in the economic recovery. Tunisia has a gross national income meeting included UN agencies (UNHCR, IOM, WHO), civil (GNI) per capita of US$10,275 purchasing power parity society (Danish Refugee Council, Islamic Relief and the (UNDP, 2018). The 2018 United Nations Development Tunisian Scouts) and donors (the European Union, and Programme (UNDP) Human Development Index (HDI) ranks the United Kingdom’s Department for International Tunisia 95 out 189 countries and 58th on the Gender Development - DFID). On this occasion, the partners Inequality Index (GII 2018). launched the rapid capacity needs assessment conducted by the Scouts in the southern regions of A key objective of the collaboration between WFP and the Tunisia, to evaluate the level of regional and local Tunisian Government is to ensure the most vulnerable girls institution’s preparedness to respond to emergencies; and boys are reached through a quality and high impact and discussed next steps including plans for WFP to conduct a Logistics Capacity Assessment. -

Successful Elimination and Prevention of Re-Establishment of Malaria in Tunisia

ELIMINATING MALARIA Case‑study 10 Successful elimination and prevention of re‑establishment of malaria in Tunisia ELIMINATING MALARIA Case‑study 10 Successful elimination and prevention of re‑establishment of malaria in Tunisia WHO Library Cataloguing‑in‑Publication Data Successful elimination and prevention of re‑establishment of malaria in Tunisia. (Eliminating malaria case‑study, 10) 1.Malaria ‑ prevention and control. 2.Malaria ‑ epidemiology. 3.National Health Programs. 4.Tunisia. I.World Health Organization. II.University of California, San Francisco. ISBN 978 92 4 150913 8 (NLM classification: WC 765) © World Health Organization 2015 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO website (www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e‑mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications –whether for sale or for non‑commercial distribution– should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO website (www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted and dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

World Bank Document

Tunisia Infrastructure Diagnostic Public Disclosure Authorized December 2019 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Final version © 2019 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for non-commercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Please cite the work as follows: 2019. Tunisia Infrastructure Diagnostic. World Bank, Washington D. C. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522- 2625; e-mail: [email protected] i Acknowledgments The World Bank Group would like to thank the Tunisian Government for its cooperation in the preparation of this report. -

Startup Ecosystem Report Sfax | Tunisia

Startup Ecosystem Report Sfax | Tunisia ISBN 978-3-96604-000-6 V 1.0 - March 2019 Startup Ecosystem Report Sfax | Tunisia Sfax | Tunisia Sfax Africa and Tunisia Tunisia and the Governorate of Sfax Sfax is the second largest city in Tunisia, with a The startup ecosystem in Sfax is developing, and has population of approximately 275.000 people. Sfax is the opportunities in the form of strong human capital, capital of the Sfax governorate, located 270 km infrastructure, and macro conditions. Access to southeast of the Tunisian capital Tunis on the finance, market factors, and a less mature startup Mediterranean coast. Founded in 849 AD, Sfax is an scene are challenges for the city. ancient city with a wealth of cultural and historical heritage. The main economic activities in the city include industry, agriculture, fishing, and international trade. Startup Ecosystem Report Sfax | Tunisia The Startup Friendliness Index (SFI) A startup ecosystem is formed by entrepreneurs, Startup Ecosystem Approach startups in their various stages, and numerous other organisations such as universities, investors, accelerators, co-working spaces, legal and financial service providers, and government agencies. Through the complex interaction of these players, a startup ecosystem has the capacity to empower entrepreneurs to develop new ideas and bring innovation to the market. The composition and maturity level of startup ecosystems are essential components of the success rate for entrepreneurs and new enterprises. A good understanding of ecosystem states, strengths, and weaknesses enables specifically-targeted policies, enhances investment decisions, and improves the impact of development cooperation. The Startup Friendliness Index (SFI) analyses the friendliness of cities for advancing entrepreneurship by measuring six key features (domains) of the startup ecosystem and the interactions between them: Human Capital, access to Finance, the liveliness of the Startup Scene, Infrastructure, Macro framework, and Market conditions. -

TUNISIA This Publication Has Been Produced with the Financial Assistance of the European Union Under the ENI CBC

DESTINATION REVIEW FROM A SOCIO-ECONOMIC, POLITICAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL PERSPECTIVE IN ADVENTURE TOURISM TUNISIA This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union under the ENI CBC Mediterranean Sea Basin Programme. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the Official Chamber of Commerce, Industry, Services and Navigation of Barcelona and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union or the Programme management structures. The European Union is made up of 28 Member States who have decided to gradually link together their know-how, resources and destinies. Together, during a period of enlargement of 50 years, they have built a zone of stability, democracy and sustainable development whilst maintaining cultural diversity, tolerance and individual freedoms. The European Union is committed to sharing its achievements and its values with countries and peoples beyond its borders. The 2014-2020 ENI CBC Mediterranean Sea Basin Programme is a multilateral Cross-Border Cooperation (CBC) initiative funded by the European Neighbourhood Instrument (ENI). The Programme objective is to foster fair, equitable and sustainable economic, social and territorial development, which may advance cross-border integration and valorise participating countries’ territories and values. The following 13 countries participate in the Programme: Cyprus, Egypt, France, Greece, Israel, Italy, Jordan, Lebanon, Malta, Palestine, Portugal, Spain, Tunisia. The Managing Authority (JMA) is the Autonomous Region of Sardinia (Italy). Official Programme languages are Arabic, English and French. For more information, please visit: www.enicbcmed.eu MEDUSA project has a budget of 3.3 million euros, being 2.9 million euros the European Union contribution (90%).