Successful Elimination and Prevention of Re-Establishment of Malaria in Tunisia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tunisia Summary Strategic Environmental and Social

PMIR Summary Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT: ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE MODERNIZATION PROJECT COUNTRY: TUNISIA SUMMARY STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT (SESA) Project Team: Mr. P. M. FALL, Transport Engineer, OITC.2 Mr. N. SAMB, Consultant Socio-Economist, OITC.2 Mr. A. KIES, Consultant Economist, OITC 2 Mr. M. KINANE, Principal Environmentalist, ONEC.3 Mr. S. BAIOD, Consultant Environmentalist ONEC.3 Project Team Sector Director: Mr. Amadou OUMAROU Regional Director: Mr. Jacob KOLSTER Division Manager: Mr. Abayomi BABALOLA 1 PMIR Summary Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment Project Name : ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE MODERNIZATION PROJECT Country : TUNISIA Project Number : P-TN-DB0-013 Department : OITC Division: OITC.2 1 Introduction This report is a summary of the Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment (SESA) of the Road Project Modernization Project 1 for improvement works in terms of upgrading and construction of road structures and primary roads of the Tunisian classified road network. This summary has been prepared in compliance with the procedures and operational policies of the African Development Bank through its Integrated Safeguards System (ISS) for Category 1 projects. The project description and rationale are first presented, followed by the legal and institutional framework in the Republic of Tunisia. A brief description of the main environmental conditions is presented, and then the road programme components are presented by their typology and by Governorate. The summary is based on the projected activities and information contained in the 60 EIAs already prepared. It identifies the key issues relating to significant impacts and the types of measures to mitigate them. It is consistent with the Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) developed to that end. -

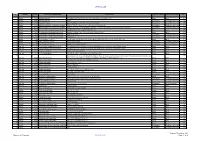

December 2020 Contract Pipeline

OFFICIAL USE No Country DTM Project title and Portfolio Contract title Type of contract Procurement method Year Number 1 2021 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways SupervisionRehabilitation Contract of Tirana-Durres for Rehabilitation line and ofconstruction the Durres of- Tirana a new Railwaylink to TIA Line and construction of a New Railway Line to Tirana International Works Open 2 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Airport Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 3 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Asset Management Plan and Track Access Charges Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 4 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Albania: Tourism-led Model For Local Economic Development Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 5 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Infrastructure and Tourism Enabling Programme: Gender and Economic Inclusion Programme Manager Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 6 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Rehabilitation of Vlore - Orikum Road (10.6 km) Works Open 2022 7 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Upgrade of Zgosth - Ura e Cerenecit road Section (47.1km) Works Open 2022 8 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Works supervision Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 9 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity PIU support Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 10 Albania 51908 Kesh Floating PV Project Design, build and operation of the floating photovoltaic plant located on Vau i Dejës HPP Lake Works Open 2021 11 Albania 51908 -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

Tunisia-Events in Bizerta-Fact Finding Mission Report-1961-Eng

Report of the Committee of Enquiry into Events in Bizerta, Tunisia Between the 18th and 24th July, 1961 INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION OF JURISTS GENEVA 1961 The International Commission of Jurists is a non-governmental organization which has Consultative Status, Category “B”, with the United Nations Eco nomic and Social Council. The Commission seeks to foster understanding of and respect for the Rule of Law. The Members of the Commission are: JOSEPH T. THORSON President of the Exchequer Court of Canada (Honorary President) VIVIAN BOSE Former Judge of the Supreme Court of India (President) PER T. FEDERSPIEL President of the Council of Europe; Member of (Vice-President) the Danish Parliament; Barrister-at-Law, Copen hagen JOS£ T. NABUCO Member of the Bar of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (Vice-President) SIR ADETOKUNBO A. ADEMOLA Chief Justice of Nigeria ARTURO A. ALAFRIZ President of the Federation of Bar Associations of the Philippines GIUSEPPE BETTIOL Member of the Italian Parliament; Professor of Law at the University of Padua DUDLEY B. BONSAL Immediate Past President of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York, USA PHILIPPE N. BOULOS Former Governor of Beirut; former Minister of Justice of Lebanon J. J. CARBAJAL VICTORICA Attorney-at-Law; Professor of Public Law at the University of Montevideo, Uruguay; former Minister U CHAN HTOON Judge of the Supreme Court of the Union of Burma A. J. M. VAN DAL Attorney-at-Law at the Supreme Court of the Netherlands SIR OWEN DIXON Chief Justice of Australia ISAAC FORSTER First President of the Supreme Court of the Republic of Senegal OSVALDO ILLANES BENITEZ Judge of the ‘Supreme Court of Chile JEAN KREHER Advocate at the Court of Appeal, Paris, France AXEL HENRIK MUNKTELL Member of the Swedish Parliament; Professor of Law at the University of Uppsala PAUL-MAURICE ORBAN Professor of Law at the University of Ghent; former Minister; former Senator STEFAN OSUSKY Former Minister of Czechoslovakia to Great Britain and France; former Member of the Czechoslovak Government LORD SHAWCROSS Former Attorney-General of England BENJAMIN R. -

Good Governance and Anti-Corruption in Tunisia Project Highlights – September 2019

Good Governance and Anti-Corruption in Tunisia Project Highlights – September 2019 Good Governance and Anti-Corruption in Tunisia 1 Good Governance and Anti-Corruption in Tunisia This brochure provides an overview of the project “Good Governance and Anti-Corruption in Tunisia”, its objectives, main achievements and the way forward. With the financial support of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office of the UK, the OECD is implementing this project in coordination with its Tunisian counterparts over a period of 3 years, from 2017 until 2020. Signing Ceremony for the UK-Tunisia Memorandum of Understanding with (from left to right) Mrs. Louise de Sousa, Ambassador of the United Kingdom to Tunisia, Mr. Alistair Burt, Minister of State for the Middle East of the United Kingdom, Mr. Kamel Ayadi, President Objective of the project of HCCAF, Tunisia, Mr. Rolf Alter, Director of the OECD Public Governance Directorate and The project aims to enhance stability, prosperity and Mr. Hedi Mekni, Secretary General of the Tunisian Government (Tunis, 3 August 2017) citizens’ trust in Tunisia. It accompanies Tunisia in fulfilling its good governance commitments of the London Anti-Corruption Conference and in implementing Partners & Beneficiaries: the 2016-2020 national anti-corruption strategy. Presidency of the Government, Ministry of Civil Three focus areas Service, Modernisation of Administration and Public Building on the work of the MENA-OECD Governance Policies, Ministry of Local Affairs and Environment, Programme and the OECD Recommendations on Public -

Geospatial Risk Analysis of Mosquito-Borne Disease Vectors in the Netherlands

Geospatial risk analysis of mosquito-borne disease vectors in the Netherlands Adolfo Ibáñez-Justicia Thesis committee Promotor Prof. Dr W. Takken Personal chair at the Laboratory of Entomology Wageningen University & Research Co-promotors Dr C.J.M. Koenraadt Associate professor, Laboratory of Entomology Wageningen University & Research Dr R.J.A. van Lammeren Associate professor, Laboratory of Geo-information Science and Remote Sensing Wageningen University & Research Other members Prof. Dr G.M.J. Mohren, Wageningen University & Research Prof. Dr N. Becker, Heidelberg University, Germany Prof. Dr J.A. Kortekaas, Wageningen University & Research Dr C.B.E.M. Reusken, National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, Bilthoven, The Netherlands This research was conducted under the auspices of the C.T. de Wit Graduate School for Production Ecology & Resource Conservation Geospatial risk analysis of mosquito-borne disease vectors in the Netherlands Adolfo Ibáñez-Justicia Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus, Prof. Dr A.P.J. Mol, in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Friday 1 February 2019 at 4 p.m. in the Aula. Adolfo Ibáñez-Justicia Geospatial risk analysis of mosquito-borne disease vectors in the Netherlands, 254 pages. PhD thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, the Netherlands (2019) With references, with summary in English ISBN 978-94-6343-831-5 DOI https://doi.org/10.18174/465838 -

Malaria Investigative Guidelines February 2021

PUBLIC HEALTH DIVISION Acute and Communicable Disease Prevention Malaria Investigative Guidelines February 2021 1. DISEASE REPORTING 1.1 Purpose of Reporting and Surveillance 1. To ensure adequate treatment of cases, particularly those with potentially fatal Plasmodium falciparum malaria. 2. To identify case contacts who may benefit from screening or treatment, e.g., fellow travelers or recipients of blood products. 3. To identify loci of malaria acquisition among Oregon travelers. 4. To contribute adequate case reports to the national database, which, in turn, gives us a better sense of the characteristics of and risk factors for malaria in the United States. 5. Conceivably, to identify persons exposed locally and to initiate appropriate follow-up. 1.2 Laboratory and Physician Reporting Requirements 1. Laboratories, physicians, and others providing health care must report confirmed or suspected cases to the Local Health Department (LHD) within one working day of identification or diagnosis. 2. Although no required, diagnostic laboratories are encouraged to send purple- top (i.e., EDTA) whole blood specimens to the Oregon State Public Health Laboratory (OSPHL) for susceptibility testing by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) upon request. 1.3 Local Health Department Reporting and Follow-Up Responsibilities 1. Report all confirmed and presumptive (but not suspect) cases (see definitions below) to the Oregon Public Health Division (OPHD) within one working day of initial physician or lab report. See §3 for case definitions. 2. Interview all confirmed and presumptive cases. 3. Identify significant contacts and educate them about the signs and symptoms of illness. Offer testing at OSPHL as appropriate. -

S.No Governorate Cities 1 L'ariana Ariana 2 L'ariana Ettadhamen-Mnihla 3 L'ariana Kalâat El-Andalous 4 L'ariana Raoued 5 L'aria

S.No Governorate Cities 1 l'Ariana Ariana 2 l'Ariana Ettadhamen-Mnihla 3 l'Ariana Kalâat el-Andalous 4 l'Ariana Raoued 5 l'Ariana Sidi Thabet 6 l'Ariana La Soukra 7 Béja Béja 8 Béja El Maâgoula 9 Béja Goubellat 10 Béja Medjez el-Bab 11 Béja Nefza 12 Béja Téboursouk 13 Béja Testour 14 Béja Zahret Mediou 15 Ben Arous Ben Arous 16 Ben Arous Bou Mhel el-Bassatine 17 Ben Arous El Mourouj 18 Ben Arous Ezzahra 19 Ben Arous Hammam Chott 20 Ben Arous Hammam Lif 21 Ben Arous Khalidia 22 Ben Arous Mégrine 23 Ben Arous Mohamedia-Fouchana 24 Ben Arous Mornag 25 Ben Arous Radès 26 Bizerte Aousja 27 Bizerte Bizerte 28 Bizerte El Alia 29 Bizerte Ghar El Melh 30 Bizerte Mateur 31 Bizerte Menzel Bourguiba 32 Bizerte Menzel Jemil 33 Bizerte Menzel Abderrahmane 34 Bizerte Metline 35 Bizerte Raf Raf 36 Bizerte Ras Jebel 37 Bizerte Sejenane 38 Bizerte Tinja 39 Bizerte Saounin 40 Bizerte Cap Zebib 41 Bizerte Beni Ata 42 Gabès Chenini Nahal 43 Gabès El Hamma 44 Gabès Gabès 45 Gabès Ghannouch 46 Gabès Mareth www.downloadexcelfiles.com 47 Gabès Matmata 48 Gabès Métouia 49 Gabès Nouvelle Matmata 50 Gabès Oudhref 51 Gabès Zarat 52 Gafsa El Guettar 53 Gafsa El Ksar 54 Gafsa Gafsa 55 Gafsa Mdhila 56 Gafsa Métlaoui 57 Gafsa Moularès 58 Gafsa Redeyef 59 Gafsa Sened 60 Jendouba Aïn Draham 61 Jendouba Beni M'Tir 62 Jendouba Bou Salem 63 Jendouba Fernana 64 Jendouba Ghardimaou 65 Jendouba Jendouba 66 Jendouba Oued Melliz 67 Jendouba Tabarka 68 Kairouan Aïn Djeloula 69 Kairouan Alaâ 70 Kairouan Bou Hajla 71 Kairouan Chebika 72 Kairouan Echrarda 73 Kairouan Oueslatia 74 Kairouan -

Potential Use of Seaweeds in Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis Niloticus) Diets

Potential use of seaweeds in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) diets Mensi F., Jamel K., Amor E.A. in Montero D. (ed.), Basurco B. (ed.), Nengas I. (ed.), Alexis M. (ed.), Izquierdo M. (ed.). Mediterranean fish nutrition Zaragoza : CIHEAM Cahiers Options Méditerranéennes; n. 63 2005 pages 151-154 Article available on line / Article disponible en ligne à l’adresse : -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- http://om.ciheam.org/article.php?IDPDF=5600075 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- To cite this article / Pour citer cet article -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Mensi F., Jamel K., Amor E.A. Potential use of seaweeds in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) diets. In : Montero D. (ed.), Basurco B. (ed.), Nengas I. (ed.), Alexis M. (ed.), Izquierdo M. (ed.). Mediterranean fish nutrition. Zaragoza : CIHEAM, 2005. p. 151-154 (Cahiers Options Méditerranéennes; n. 63) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- http://www.ciheam.org/ http://om.ciheam.org/ Potential use of seaweeds in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) -

The Sousse Church

THE SOUSSE CHURCH Senior Pastor Opportunity Profile About The Sousse Church The Sousse Church is comprised of sub-Saharan African students, a few expats, a few Tunisians and the occasional tourist. The congregation of 20-30 is unable to support a full-time pastor, so the applicant will need to have his own support base. Few expats live in Sousse; this is a primarily missional position. The Sousse Church meets in the local Catholic church's annex, in a renovated room that is perfect for the congregation. COVID-19 has temporarily halted in-person services, but they are scheduled to resume in early 2021. The church meets in a member's home for now. There are regular Bible studies and prayer meetings, and several home groups in French and Arabic for curious Tunisians. The Sousse Church is the only recognized Protestant church in the city, and the pastor will be granted a resident visa and respected as a church leader. About Sousse, Tunisia Sousse is a tourist city on the Mediterranean coast. There are many secular people in the city, as well as many conservative families. Tunisia is a true mix of both and is the only lasting democracy to come out of the Arab Spring in 2011. The Sousse area has a population of 250,000, with a mild Mediterranean climate. It is two hours south of the capital city of Tunis by car. Women in the city dress in a wide variety of ways, and females drive vehicles regularly in the city. There is almost no violent crime; petty theft is fairly common. -

Inventory of Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants of Coastal Mediterranean Cities with More Than 2,000 Inhabitants (2010)

UNEP(DEPI)/MED WG.357/Inf.7 29 March 2011 ENGLISH MEDITERRANEAN ACTION PLAN Meeting of MED POL Focal Points Rhodes (Greece), 25-27 May 2011 INVENTORY OF MUNICIPAL WASTEWATER TREATMENT PLANTS OF COASTAL MEDITERRANEAN CITIES WITH MORE THAN 2,000 INHABITANTS (2010) In cooperation with WHO UNEP/MAP Athens, 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .........................................................................................................................1 PART I .........................................................................................................................3 1. ABOUT THE STUDY ..............................................................................................3 1.1 Historical Background of the Study..................................................................3 1.2 Report on the Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants in the Mediterranean Coastal Cities: Methodology and Procedures .........................4 2. MUNICIPAL WASTEWATER IN THE MEDITERRANEAN ....................................6 2.1 Characteristics of Municipal Wastewater in the Mediterranean.......................6 2.2 Impact of Wastewater Discharges to the Marine Environment........................6 2.3 Municipal Wasteater Treatment.......................................................................9 3. RESULTS ACHIEVED ............................................................................................12 3.1 Brief Summary of Data Collection – Constraints and Assumptions.................12 3.2 General Considerations on the Contents -

Tunisia 01 April - 30 June 2017

OPERATIONAL UPDATE Tunisia 01 April - 30 June 2017 Tunisia is a country that has In Tunisia, UNHCR’s priorities are Together with Tunisian maintained an open-door policy to support the development of a authorities and its partner to people fleeing conflict and national asylum system and ADRA, UNHCR assists persecutions. build national capacities and to registered urban refugees and protect and assist refugees and asylum seekers to become asylum seekers. self-reliant. FUNDING REQUIREMENT (AS OF 7 AUGUST 2017) Priorities Support Tunisian authorities into establishing a USD 5.8 M requested for Tunisia national asylum system and progressively assuming refugee protection functions; Provide protection and assistance to refugees and asylum seekers in Tunisia and support them to Funded become self-reliant; 12% Build national capacities to prepare and respond to refugee emergencies, in a context of mixed migration. Key figures 68 most vulnerable refugees and asylum-seekers received financial assistance in June 2017. So far in 2017, 27 refugees signed working contracts and 28 benefited from vocational trainings. Gap 177 people were rescued at sea off Tunisian coast 88% so far in 2017. So far, 14 among them have approached UNHCR to claim asylum in Tunisia. POPULATION OF CONCERN TO UNHCR Countries of origin Syria 461 Palestine 31 Sudan 32 Iraq 20 Other nationalities* 82 Others of Concern** 4 TOTAL: 630 (Figures as of 30 June 2017) * Other nationalities (17) ** Others of Concern: specific groups of persons not normally falling under the mandate of UNHCR, but to whom extends protection and/or assistance. www.unhcr.org 1 OPERATIONAL UPDATE > Tunisia / 01 April-30 June 2017 Update On Achievements Operational Context .