Some Adaptive Features of Seabird Plumage Types K. E. L. Simmons Plates 69-J 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation Problems on Tristan Da Cunha Byj

28 Oryx Conservation Problems on Tristan da Cunha ByJ. H. Flint The author spent two years, 1963-65, as schoolmaster on Tristan da Cunha, during which he spent four weeks on Nightingale Island. On the main island he found that bird stocks were being depleted and the islanders taking too many eggs and young; on Nightingale, however, where there are over two million pairs of great shearwaters, the harvest of these birds could be greater. Inaccessible Island, which like Nightingale, is without cats, dogs or rats, should be declared a wildlife sanctuary. Tl^HEN the first permanent settlers came to Tristan da Cunha in " the early years of the nineteenth century they found an island rich in bird and sea mammal life. "The mountains are covered with Albatross Mellahs Petrels Seahens, etc.," wrote Jonathan Lambert in 1811, and Midshipman Greene, who stayed on the island in 1816, recorded in his diary "Sea Elephants herding together in immense numbers." Today the picture is greatly changed. A century and a half of human habitation has drastically reduced the larger, edible species, and the accidental introduction of rats from a shipwreck in 1882 accelerated the birds' decline on the main island. Wood-cutting, grazing by domestic stock and, more recently, fumes from the volcano have destroyed much of the natural vegetation near the settlement, and two bird subspecies, a bunting and a flightless moorhen, have become extinct on the main island. Curiously, one is liable to see more birds on the day of arrival than in several weeks ashore. When I first saw Tristan from the decks of M.V. -

Red-Footed Booby Helper at Great Frigatebird Nests

264 SHORT COMMUNICATIONS NECTS MEANS ECTS MEANS ICATE SAMPLE SIZE S.D. SAMPLE SIZE 70 IN DAYS FIGURE 2. Culmen length against age of Brown FIGURE 1. Weight against age of Brown Noddy Noddy chicks on Manana Island, Hawaii in 1972. chicks on Manana Island, Hawaii in 1972. about the thirty-fifth day; apparently Brown Noddies on Christmas Island grow more rapidly than those on 5.26 g/day (SD = 1.18 g/day), and chick growth rate Manana. More data are required for a refined analysis and fledging age were negatively correlated (r = of intraspecific variation in growth rates of Brown -0.490, N = 19, P < 0.05). Noddy young. Seventeen of the chicks were weighed both at the This paper is based upon my doctoral dissertation age of fledging and from 3 to 12 days later; there was submitted to the University of Hawaii. I thank An- no significant recession in weight after fledging (t = drew J. Berger for guidance and criticism. The 1.17, P > 0.2), as suggested for certain terns (e.g., Hawaii State Division of Fish and Game kindly LeCroy and LeCroy 1974, Bird-Banding 45:326). granted me permission to work on Manana. This Dorward and Ashmole (1963, Ibis 103b: 447) mea- study was supported by the Department of Zoology sured growth in weight and culmen length of Brown of the University of Hawaii, by an NSF Graduate Noddies on Ascension Island in the Atlantic; scatter Fellowship, and by a Mount Holyoke College Faculty diagrams of their data indicate growth functions very Grant. -

Kendall Birds

Kendall-Frost Reserve Breeding Common Name Scientific Name Regulatory Status Status Waterfowl - Family Anatidae Brant Branta bernicla W Special Concern Gadwall Ana strepera W American Wigeon Anas americana W Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Y Cinnamon Teal Anas cyanoptera W Northern Shoveler Anas clypeata W Northern Pintail Anas acuta W Green-winged Teal Anas crecca W Redhead Aythya americana W Lesser Scaup Aythya affinis W Bufflehead Bucephala albeola W Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator W Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis W Loons - Family Gaviidae Common Loon Gavia immer W Special Concern Grebes - Family Podicipedidae Pied-billed Grebe Podilymbus podiceps W Horned Grebe Podiceps auritus W Eared Grebe Podiceps nigricollis W Western Grebe Aechmophorus occidentalis W Clark's Grebe Aechmophorus clarkii W Pelicans - Family Pelecanidae Brown Pelican Pelecanus occidentalis Y Endangered Frigatebirds - Family Fregatidae Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens X Cormorants - Family Phalacrocoracide Double-crested Cormorant Phalacrocorax auritus Y Herons and Bitterns - Family Ardeidae Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias Y Great Egret Ardea alba Y Snowy Egret Egretta thula Y Little Blue Heron Egretta caerulea Y Green Heron Butorides virescens Y Black-crowned Night Heron Nycticorax nycticorax Y Hawks, Kites and Eagles - Family Accipitridae Osprey Pandion haliaetus Y White-tailed Kite Elanus leucurus W Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus W Special Concern Cooper's Hawk Accipiter cooperii Y Red-shouldered Hawk Buteo lineatus Y Red-tailed Hawk Buteo jamaicensis -

Iucn Red Data List Information on Species Listed On, and Covered by Cms Appendices

UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC4/Doc.8/Rev.1/Annex 1 ANNEX 1 IUCN RED DATA LIST INFORMATION ON SPECIES LISTED ON, AND COVERED BY CMS APPENDICES Content General Information ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Species in Appendix I ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Mammalia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Aves ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Reptilia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 Pisces ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

MAGNIFICENT FRIGATEBIRD Fregata Magnificens

PALM BEACH DOLPHIN PROJECT FACT SHEET The Taras Oceanographic Foundation 5905 Stonewood Court - Jupiter, FL 33458 - (561-762-6473) [email protected] MAGNIFICENT FRIGATEBIRD Fregata magnificens CLASS: Aves ORDER: Suliformes FAMILY: Fregatidae GENUS: Fregata SPECIES: magnificens A long-winged, fork-tailed bird of tropical oceans, the Magnificent Frigatebird is an agile flier that snatches food off the surface of the ocean and steals food from other birds. It breeds mostly south of the United States, but wanders northward along the coasts during nonbreeding season. Physical Appearance: Frigate birds are the only seabirds where the male and female look strikingly different. All have pre- dominantly black plumage, long, deeply forked tails and long hooked bills. Females have white underbellies and males have a distinctive red throat pouch, which they inflate during the breeding season to attract females Their wings are long and pointed and can span up to 2.3 meters (7.5 ft), the largest wing area to body weight ratio of any bird. These birds are about 35-45 inches ((89 to 114 cm) in length, and weight between 35 and 67 oz (1000-1900 g). The bones of frigate birds are markedly pneumatic (filled with air), making them very light and contribute only 5% to total body weight. The pectoral girdle (shoulder joint) is strong as its bones are fused. Habitat: Frigate birds are found across all tropical oceans. Breeding habitats include mangrove cays on coral reefs, and decidu- ous trees and bushes on dry islands. Feeding range while breeding includes shallow water within lagoons, coral reefs, and deep ocean out of sight of land. -

Breeding Biology of the Brown Noddy on Tern Island, Hawaii

Wilson Bull., 108(2), 1996, pp. 317-334 BREEDING BIOLOGY OF THE BROWN NODDY ON TERN ISLAND, HAWAII JENNIFER L. MEGYESI’ AND CURTICE R. GRIFFINS ABSTRACT.-we observed Brown Noddy (Anous stolidus pileatus) breeding phenology and population trends on Tern Island, French Frigate Shoals, Hawaii, from 1982 to 1992. Peaks of laying ranged from the first week in January to the first week in November; however, most laying occurred between March and September each year. Incubation length was 34.8 days (N = 19, SD = 0.6, range = 29-37 days). There were no differences in breeding pairs between the measurements of the first egg laid and successive eggs laid within a season. The proportion of light- and dark-colored chicks was 26% and 74%, respectively (N = 221) and differed from other Brown Noddy colonies studied in Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The length of time between clutches depended on whether the previous outcome was a failed clutch or a successfully fledged chick. Hatching, fledging, and reproductive success were significantly different between years. The subspecies (A. s. pihtus) differs in many aspects of its breeding biology from other colonies in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, in regard to year-round occurrence at the colony, frequent renesting attempts, large egg size, proportion of light and dark colored chicks, and low reproductive success caused by in- clement weather and predation by Great Frigatebirds (Fregata minor). Received 31 Mar., 1995, accepted 5 Dec. 1995. The Brown Noddy (Anous stolidus) is the largest and most widely distributed of the tropical and subtropical tern species (Cramp 1985). -

Noio Or Black Noddy Anous Minutus

Seabirds Noio or Black Noddy Anous minutus SPECIES STATUS: State recognized as Indigenous NatureServe Heritage Rank G5 - Secure North American Waterbird Conservation Plan – Photo: USFWS Moderate concern Regional Seabird Conservation Plan - USFWS 2005 SPECIES INFORMATION: The noio or black noddy is a medium-sized, abundant, and gregarious tern (Family: Laridae) with a pantropical distribution. Seven noio (black noddy) subspecies are generally recognized, and two are resident in Hawai‘i: A. s. melanogenys (MHI) and A. s. marcusi (NWHI). Individuals have slender wings, a wedge-shaped tail, and black bill which is slightly decurved. Adult males and females are sooty black with a white cap and have reddish brown legs and feet; bill droops slightly. Flight is swift with rapid wing beats and usually direct and low over the ocean; this species almost never soars high. Often forages in large, mixed species flocks associated with schools of large predatory fishes which drive prey species to the surface. Noio (black noddy) generally forage in nearshore waters and feeds mainly by dipping the surface from the wing or by making shallow dives. Opportunistic, in Hawai‘i, noio (black noddy) primarily takes juvenile goatfish, lizardfish, herring, flyingfish, and gobies. Nests in large, dense colonies that include non-breeding juvenile birds. Established pairs return to the same nest site year after year. Breeding is highly variable and egg laying occurs year-round. Both parents incubate single egg, and brood and feed chick. Birds first breed at two to three years of age, and the oldest known individual was 25 years old. DISTRIBUTION: Noio (black noddy) breed throughout the Hawaiian Archipelago, including all islands of NWHI and the coastal cliffs and offshore islets of MHI. -

Plumage and Sexual Maturation in the Great Frigatebird Fregata Minor in the Galapagos Islands

Valle et al.: The Great Frigatebird in the Galapagos Islands 51 PLUMAGE AND SEXUAL MATURATION IN THE GREAT FRIGATEBIRD FREGATA MINOR IN THE GALAPAGOS ISLANDS CARLOS A. VALLE1, TJITTE DE VRIES2 & CECILIA HERNÁNDEZ2 1Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Colegio de Ciencias Biológicas y Ambientales, Campus Cumbayá, Jardines del Este y Avenida Interoceánica (Círculo de Cumbayá), PO Box 17–12–841, Quito, Ecuador ([email protected]) 2Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Departamento de Ciencias Biológicas, PO Box 17–01–2184, Quito, Ecuador Received 6 September 2005, accepted 12 August 2006 SUMMARY VALLE, C.A., DE VRIES, T. & HERNÁNDEZ, C. 2006. Plumage and sexual maturation in the Great Frigatebird Fregata minor in the Galapagos Islands. Marine Ornithology 34: 51–59. The adaptive significance of distinctive immature plumages and protracted sexual and plumage maturation in birds remains controversial. This study aimed to establish the pattern of plumage maturation and the age at first breeding in the Great Frigatebird Fregata minor in the Galapagos Islands. We found that Great Frigatebirds attain full adult plumage at eight to nine years for females and 10 to 11 years for males and that they rarely attempted to breed before acquiring full adult plumage. The younger males succeeded only at attracting a mate, and males and females both bred at the age of nine years when their plumage was nearly completely adult. Although sexual maturity was reached as early as nine years, strong competition for nest-sites may further delay first reproduction. We discuss our findings in light of the several hypotheses for explaining delayed plumage maturation in birds, concluding that slow sexual and plumage maturation in the Great Frigatebird, and perhaps among all frigatebirds, may result from moult energetic constraints during the subadult stage. -

Proposal for Inclusion of the Black Noddy Subspecies Worcesteri

CMS Distribution: General CONVENTION ON MIGRATORY UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.1.12 15 June 2017 SPECIES Original: English 12th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Manila, Philippines, 23 - 28 October 2017 Agenda Item 25.1 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF THE BLACK NODDY (Anous minutus) SUBSPECIES worcesteri ON APPENDIX II OF THE CONVENTION Summary: The Government of the Philippines has submitted the attached proposal* for the inclusion of the Black Noddy (Anous minutus) subspecies worcesteri on Appendix II of CMS. *The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CMS Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.1.12 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF THE BLACK NODDY (Anous minutus) SUBSPECIES worcesteri ON APPENDIX II OF THE CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF MIGRATORY SPECIES OFWILD ANIMALS A. PROPOSAL This proposal is for the inclusion of Black Noddy (Anous minutus) subspecies worcesteri in Appendix II. The species is classified as Endangered on account of a very small population which breeds within a tiny area of occupancy on just two islets, and is projected to decline by more than 70 per cent over the next 10 to 15 years. B. PROPONENT: Government of the Republic of the Philippines C. SUPPORTING STATEMENT 1. Taxonomy 1.1 Class: Aves 1.2 Order: Charadriiformes 1.3 Family: Laridae 1.4 Genus, species or subspecies, including author and year: Anous minutus worcesteri (McGregor, 1911) 1.5 Scientific synonyms: No known synonyms 1.6 Common name(s), in all applicable languages used by the Convention: English - Black Noddy French - Noddi noir Spanish - Tiñosa menuda 2. -

State of Nature Report

STATE OF NATURE Foreword by Sir David Attenborough he islands that make up the The causes are varied, but most are (ButterflyHelen Atkinson Conservation) United Kingdom are home to a ultimately due to the way we are using Twonderful range of wildlife that our land and seas and their natural is dear to us all. From the hill-walker resources, often with little regard for marvelling at an eagle soaring overhead, the wildlife with which we share them. to a child enthralled by a ladybird on The impact on plants and animals has their fingertip, we can all wonder at been profound. the variety of life around us. Although this report highlights what However, even the most casual of we have lost, and what we are still observers may have noticed that all is losing, it also gives examples of how not well. They may have noticed the we – as individuals, organisations, loss of butterflies from a favourite governments – can work together walk, the disappearance of sparrows to stop this loss, and bring back nature from their garden, or the absence of where it has been lost. These examples the colourful wildflower meadows of should give us hope and inspiration. their youth. To gain a true picture of the balance of our nature, we require We should also take encouragement a broad and objective assessment of from the report itself; it is heartening the best available evidence, and that is to see so many organisations what we have in this groundbreaking coming together to provide a single State of Nature report. -

An Analysis of Physical, Physiological, and Optical Aspects of Avian Coloration with Emphasis on Wood-Warblers

(ISBN: 0-943610-47-8) AN ANALYSIS OF PHYSICAL, PHYSIOLOGICAL, AND OPTICAL ASPECTS OF AVIAN COLORATION WITH EMPHASIS ON WOOD-WARBLERS BY EDWARD H. BURTT, JR. Department of Zoology Ohio Wesleyan University Delaware, Ohio 43015 ORNITHOLOGICAL MONOGRAPHS NO. 38 PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION WASHINGTON, D.C. 1986 AN ANALYSIS OF PHYSICAL, PHYSIOLOGICAL, AND OPTICAL ASPECTS OF AVIAN COLORATION WITH EMPHASIS ON WOOD-WARBLERS ORNITHOLOGICAL MONOGRAPHS This series,published by the American Ornithologists' Union, has been estab- lished for major papers too long for inclusion in the Union's journal, The Auk. Publication has been made possiblethrough the generosityof the late Mrs. Carl Tucker and the Marcia Brady Tucker Foundation, Inc. Correspondenceconcerning manuscripts for publication in the seriesshould be addressedto the Editor, Dr. David W. Johnston,Department of Biology, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA 22030. Copies of Ornithological Monographs may be ordered from the Assistant to the Treasurer of the AOU, Frank R. Moore, Department of Biology, University of Southern Mississippi, Southern Station Box 5018, Hattiesburg, Mississippi 39406. (See price list on back and inside back covers.) Ornithological Monographs, No. 38, x + 126 pp. Editors of OrnithologicalMonographs, David W. Johnstonand Mercedes S. Foster Special Reviewers for this issue, Sievert A. Rohwer, Department of Zo- ology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington; William J. Hamilton III, Division of Environmental Studies, University of Cal- ifornia, Davis, California Author, Edward H. Burtt, Jr., Department of Zoology, Ohio Wesleyan University, Delaware, Ohio 43015 First received, 24 October 1982; accepted 11 March 1983; final revision completed 9 April 1985 Issued May 1, 1986 Price $15.00 prepaid ($12.50 to AOU members). -

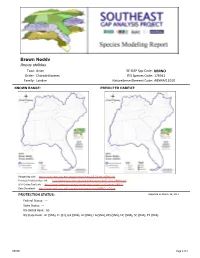

Brown Noddy Anous Stolidus Taxa: Avian SE-GAP Spp Code: Bbrno Order: Charadriiformes ITIS Species Code: 176941 Family: Laridae Natureserve Element Code: ABNNM11010

Brown Noddy Anous stolidus Taxa: Avian SE-GAP Spp Code: bBRNO Order: Charadriiformes ITIS Species Code: 176941 Family: Laridae NatureServe Element Code: ABNNM11010 KNOWN RANGE: PREDICTED HABITAT: P:\Proj1\SEGap P:\Proj1\SEGap Range Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Range_bBRNO.pdf Predicted Habitat Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Dist_bBRNO.pdf GAP Online Tool Link: http://www.gapserve.ncsu.edu/segap/segap/index2.php?species=bBRNO Data Download: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/region/vert/bBRNO_se00.zip PROTECTION STATUS: Reported on March 14, 2011 Federal Status: --- State Status: --- NS Global Rank: G5 NS State Rank: AL (SNA), FL (S1), GA (SNA), HI (SNR), LA (SNA), MS (SNA), NC (SNA), SC (SNA), TX (SNA) bBRNO Page 1 of 4 SUMMARY OF PREDICTED HABITAT BY MANAGMENT AND GAP PROTECTION STATUS: US FWS US Forest Service Tenn. Valley Author. US DOD/ACOE ha % ha % ha % ha % Status 1 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 2 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 3 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 4 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Total 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 US Dept. of Energy US Nat. Park Service NOAA Other Federal Lands ha % ha % ha % ha % Status 1 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 2 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 3 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 4 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Total 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Native Am.