The Development of the Sugar Industry In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Management of Disease Complex Inducing Grain Discolouration in Rice

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2020; 8(1): 197-199 E-ISSN: 2320-7078 P-ISSN: 2349-6800 Management of disease complex inducing grain JEZS 2020; 8(1): 197-199 © 2020 JEZS discolouration in rice crop in northern Telangana Received: 07-11-2019 Accepted: 09-12-2019 zone of the state P Vijay Kumar Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Professor P Vijay Kumar, RVT Balazzii Naaiik, B Venkata Rajkumar, M Swetha, Jayashankar Telangana State Agricultural University, Rudrur, M Bhavyamanjari, D Vijaya Lakshmi and C PadmaVeni Nizamabad, Telangana, India Abstract RVT Balazzii Naaiik Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is predominantly grown as a staple crop in the Nizamabad district of Telangana Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Professor state. The average productivity of the district varies from 5 - 6 t ha -1 and it is a major source of earning to Jayashankar Telangana State majority of farmers. Grain discoloration disease of rice is becoming a serious threat to rice production in Agricultural University, Rudrur, the district particularly in Kharif season which caused yield losses. The influence of disease incidence Nizamabad, Telangana, India and severity on grain yield and quality of the rice (Oryza sativa L.) was investigated by conducting Front B Venkata Rajkumar –line demonstration on management of Grain discoloration in Rice (var. RNR-15048) crop during three Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Professor continuous years i.e., 2017-18, 2018-19 and 2019-20 through recommended technology given by Jayashankar Telangana State PJTSAU at farmers fields in 10 locations each year (one location is equivalent to one farmer field) by Agricultural University, Rudrur, Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Rudrur, Nizamabad. -

Study of Pre Released Sugarcane Genotypes for Agronomic Traits And

Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2021; 10(1): 1928-1930 E-ISSN: 2278-4136 P-ISSN: 2349-8234 www.phytojournal.com Study of pre released sugarcane genotypes for JPP 2021; 10(1): 1928-1930 Received: 13-11-2020 agronomic traits and sugar yield Accepted: 16-12-2020 Firdoz Shahana Firdoz Shahana, Dr. Y Bharathi, Dr. T Prabhakar Reddy and Dr. B Professor, Jayashankar Joseph Telangana State Agricultural University, Regional Sugarcane and Rice Research Station, Abstract Rudrur, Nizamabad District, Study pertaining to agronomic evaluation of ten pre released sugarcane genotypes was conducted at Telangana, India RS&RRS, Rudrur, PJTSAU, Telangana state during rabi 2016-17.Genotypes 2009 R 74, 2010 R 854, 2011 R 274, 2011 R 24, 97 R 401, 2011 R 1, 2011 R 305, 2011 R 327, 2011 R 47, and 2010 R 175 were Dr. Y Bharathi studied for yield attributes, cane yield and sugar yield in comparison to popular variety 93 V 297. Professor, Jayashankar Experiment was conducted in randomized block design with genotypes as treatments replicated thrice. Telangana State Agricultural Genotypes 2011 R 274 recorded higher cane length (323.3 cm) cane girth (1.4 cm) single cane weight University, Regional Sugarcane (2.0 kg) and higher number of total internodes (22nos) and was significantly superior over 93V297. Due and Rice Research Station, Rudrur, Nizamabad District, to higher yield attributes significantly higher cane yield of 168 tons/ha was recorded with 2011 R 274, Telangana, India while 93V297 recorded cane yield of 101 tons/ha. Sucrose % and CCS yield was also superior with 2011 R 274 with 21.9% sucrose and 25.78 t/ha sugar yield. -

Assessment of Protective Clothing for Pesticide Applicators While Spraying

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2020; 8(1): 942-948 E-ISSN: 2320-7078 P-ISSN: 2349-6800 Assessment of protective clothing for pesticide JEZS 2020; 8(1): 942-948 © 2020 JEZS applicators while spraying in different crops Received: 14-11-2019 Accepted: 18-12-2019 M Bhavya Manjari M Bhavya Manjari, RVT Balazzii Naaiik, M Swetha, P Vijay Kumar, BV Research Associate, Department of Home Science, Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Rajkumar, D Vijaya Lakshmi, Maloth Mohan and C Padma Veni Professor Jayashankar Telangana State Agricultural University, Rudrur, Nizamabad, Telangana, India Abstract Majority of farmers rely on pesticides and fertilizers to increase yields. Farmer suffers from various RVT Balazzii Naaiik Senior Scientist, Department of ailments due to spraying of such pesticides such as nausea, vomiting, headache, skin disorders, digestive Agronomy, Programme Co-ordinator, problems and breathing problems. Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Rudrur had been used the protective clothing, Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Professor which contains Gloves, Mask, Apron (old white cotton shirt) Cap, Sun glasses, this technology proved Jayashankar Telangana State Agricultural University, Rudrur, technologically feasible, economically profitable, ecologically sustainable and culturally compatible. Nizamabad, Telangana, India Structured schedule was prepared for getting farmers response or feedback about protective clothing. Farmers opined that protective clothing has excellent to good functional features i.e suitability, comfort M Swetha Subject Matter Specialist, Department ability, durability; adoption feasibility. Majority of farmers had positive opinion about protective clothing of Agricultural Extension, Krishi Vigyan that it protects the body from external matters and reduces health hazards. Farmers expressed that with Kendra, Professor Jayashankar the utilization of protective clothing, the morbidity / health hazards were decreased over a period of time Telangana State Agricultural University, Rudrur, Nizamabad, Telangana, India from day one today thirty. -

(Cicer Arietinum L.) Variety (Nbeg-3) in Nizamabad District of Telangana

Cluster Front Line Demonstration Evaluation Programme on Bengal gram (Cicer arietinum L.) Variety (NBeG-3) in Nizamabad district of Telangana 1 2 3 4 5 M. Suresh , RVT.Balazzi Naaiik , B. Kranthi kumar , P.Vijaykumar , M.Swetha , D. Vijayalaxmi6 , B.V.Rajkumar7 , M. Bhavya manjari8 and C.Padmaveni9 1. SMS (Soil Science), Krishi Vigyan Kendra- Rudrur, Nizamabad, PJTSAU, Telangana, India. 2. Programme Coordinator, Krishi Vigyan Kendra- Rudrur, Nizamabad, PJTSAU, Telangana, India. 3. SMS (Soil science) Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Malyal, PJTSAU, Telangana, India. 4. SMS (Plant protection.), Krishi Vigyan Kendra- Rudrur, Nizamabad, PJTSAU, Telangana, India. 5. SMS (Extension), Krishi Vigyan Kendra- Rudrur, Nizamabad, PJTSAU, Telangana, India. 6. Assistant Professor (Soil science) Agricultural College, Palem, PJTSAU, Telangana, India. 7. SMS (Horticulture), Krishi Vigyan Kendra- Rudrur, Nizamabad, PJTSAU, Telangana, India. 8. RA (Home science), Krishi Vigyan Kendra- Rudrur, Nizamabad, PJTSAU, Telangana, India. 9. Assistant Director of Extension, PJTSAU, Rajendranagar, Hyderabad, Telangana, India. Abstract The present study was conducted under Krishi Vigyan Kendra (KVK), Rudrur operational area during 2017-18 to 2019-20 in the rabi seasons with 150 frontline demonstrations across twenty three villages, seven mandals of Nizamabad district of Telangana. The results of demonstrations showed that farmers could increase the Bengal gram productivity notably by switching over to improved variety and adoption of improved production technology. In front line demonstrations, it was observed that the improved Bengal gram variety NBeG-3 recorded the higher yield (2078 kg/ha) compared to the farmers' practices variety (1775 kg/ha). The demonstration yield was increased over farmer’s practices was 12.11%. Technology gap and the technology index values were 422 kg/ha and 1689, respectively. -

Of New Districts, Revenue Divisions and Mandals in Nizamabad District – Preliminary Notification - Orders – Issued

GOVERNMENT OF TELANGANA ABSTRACT District Administration – Formation/Re-Organization of new Districts, Revenue Divisions and Mandals in Nizamabad District – Preliminary Notification - Orders – Issued. REVENUE (DA-CMRF) DEPARTMENT G.O.Rt.No. 369 Dated: 22.08.2016 Read the following:- 1) Telangana Districts (Formation) Act 1974, (Act 7 of 1974). 2) From the SPL.CS & CCLA, Telangana, Hyderabad, Lr.No.Coord/350/2015 dated 21.08.2016. ORDER:- The appended notification shall be published in Extra-Ordinary issue of Telangana Gazette, dated 22.08.2016. The Commissioner of Printing Stationery and Stores Purchase, Telangana State, Hyderabad is requested to furnish 100 copies of the Gazette notification for the use of the Government. 2) The District Collector, Nizamabad is requested to publish the preliminary notification in English and Telugu in the District Gazette for information of the public and give wide publicity in all concerned areas. ( BY ORDER AND IN THE NAME OF THE GOVERNOR OF TELANGANA) K.PRADEEP CHANDRA SPECIAL CHIEF SECETARY TO GOVERNMENT To The Commissioner of Printing, Stationery & Stores Purchase, T.S. Hyd. The Spl CS & Chief Commissioner of Land Administration, T.S., Hyderabad. The District Collector, Nizamabad. The Director of Census Operations, T.S., Hyderabad . The Account General, T.S., Hyderabad. The Director of Treasuries and Accounts, T.S. Hyderabad. All the District Collectors/All Heads of Departments. The PR & RD (Mandals) Department./The G.A (Elections/Spl.) Department. The Commissioner of Information and Public Relations, T.S., Hyderabad. All Departments of Secretariat / General Administration (Cabinet) Department Copy to: The P.S.to Prl. Secretary to Chief Minister/ P.S. -

Kamareddy-Nizamabad-Districts

10/17/2019 KAMAREDEDY DISTRICT We acknowledge the content from: https://kamareddy.telangana.gov.in › document › district-profile The district is spread over an area of 3,652.00 square kilometres (1,410.05 sq mi) making it the 15th largest district in the state.[4] Kamareddy is bounded by Nizamabad district on North, Sircilla district and Siddipet district on East and South East respectively, it is bounded on South by Sangareddy district and Medak district and on the West and South West by Nanded district and Bidar district of Maharashtra and Karnataka states respectively. NATURAL RESOURCES FOREST: The total Forest area in the District 82,190.48 Hectares farming 22.43 percent of the Total Geographical Area of the District. The thick Forest belt produces Timber, Fuel, Bamboo and Beedi Leaves, which yield good revenue. Custard Apples grow well in this District. 1/3 10/17/2019 SOILS: The important soils are Black Soils and Chalka ( Sandy Loamy ) and they constitute 52 Percent and 48 Percent of Total Area of the District respectively. The erstwhile blocks of Madnoor and Banswada are predominantly covered by Black Soils and other area of the district is covered with Chalka Soils MINERALS: The district is not rich in minerals, Iron ore of poor quality occurs at a few places as laterite and ferrogenous quartizites. Aluminous boles containing 24% to 35% alumina are reported from Gurja Kunta of Bhiknoor Mandal and Karedpally in Tadwai Mandal. White calcareous Kaolinised earth is found near Tippapur, Bhiknoor and Kupriyal. Granites of various quartzes and Deccan trap rocks yield excellent material for buildings and roads. -

In Nizamabad District of Telangana

Current Journal of Applied Science and Technology 39(48): 312-317, 2020; Article no.CJAST.63278 ISSN: 2457-1024 (Past name: British Journal of Applied Science & Technology, Past ISSN: 2231-0843, NLM ID: 101664541) Cluster Front Line Demonstration Evaluation Programme on Bengal Gram (Cicer arietinum L.) Variety (NBeG-3) in Nizamabad District of Telangana 1* 1 2 1 M. Suresh , R. V. T. Balazzi Naaiik , B. Kranthi Kumar , P. Vijaykumar , M. Swetha1, D. Vijayalaxmi3, B. V. Rajkumar1, M. Bhavya Manjari1 and C. Padmaveni4 1Krishi Vigyan Kendra- Rudrur, Nizamabad, PJTSAU, Telangana, India. 2Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Malyal, PJTSAU, Telangana, India. 3Soil Science, Agricultural College, Palem, PJTSAU, Telangana, India. 4PJTSAU, Rajendranagar, Hyderabad, Telangana, India. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration among all authors. Authors MS, RVTBN, BKK, DV and CP designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, wrote the protocol and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors PV and BVR managed the analyses of the study. Authors MBM and MS managed the literature searches. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/CJAST/2020/v39i4831236 Editor(s): (1) Dr. Nhamo Nhamo, Zimbabwe Open University, Zimbabwe. Reviewers: (1) Udokang Anietie Edem, Federal Polytechnic Offa, Nigeria. (2) Florin Sala, Banat University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine "King Michael I of Romania", Romania. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle4.com/review-history/63278 Received 24 October 2020 Accepted 28 December 2020 Original Research Article Published 31 December 2020 ABSTRACT The present study was conducted under Krishi Vigyan Kendra (KVK), Rudrur operational area during 2017-18 to 2019-20 in the rabi seasons with 150 frontline demonstrations across twenty three villages, seven mandals of Nizamabad district of Telangana. -

Food Security by Promotion of Pulses Through KVK Methodology – a Way of Doubling the Farmers Income

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2018) 7(10): 2585-2596 International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 7 Number 10 (2018) Journal homepage: http://www.ijcmas.com Review Article https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2018.710.300 Food Security by Promotion of Pulses through KVK Methodology – A Way of Doubling the Farmers Income C. Padma Veni1*, Bandaru Venkata Rajkumar2, D. Vijaya Lakshmi3, M. Swetha4, P. Vijay Kumar5, M. Bhavya Manjari6 and K. Dattatri7 1(Agril. Extension) & Programme Coordinator, KVK, Rudrur, Telangana, India 2(Horticulture), KVK, Rudrur, Telangana, India 3(Crop Production), KVK, Rudrur, Telangana, India 4(Agril. Extension), KVK, Rudrur, Telangana, India 5(Plant Protection), KVK, Rudrur, Telangana, India 6(Home Science), KVK, Rudrur, Telangana, India 7(Agril. Extension), ATARI, Zone-X, Hyderabad, Telangana, India *Corresponding author ABSTRACT Food security tops the Government agenda as production stagnates and prices continue to be high. Pulses on account of their vital role in nutritional security and soil ameliorative propert ies have been an integral part of sustainable agriculture since ages. Presently, the pulses are grown in 23 million hectares with 13–15 million tonnes of production in the country. National Food Security Mission on pulses, a centrally sponsored scheme is implemented in the country during 2007 with a goal to increase K e yw or ds production and productivity in pulse crops by providing farmers the high yielding variety seeds with improved technology as the Hon’ble Prime Minister Shri Narendra Food Security, Modi ji emphasised in seven points strategy document for doubling the farmer’s Promotion, KVK income by 2022. -

A Case of KVK, Rudrur, Nizamabad, Telangana State

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2018) 7(10): 2573-2584 International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 7 Number 10 (2018) Journal homepage: http://www.ijcmas.com Case Study https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2018.710.299 Farm and Home Technologies for Women Livelihood Promotion – A Case of KVK, Rudrur, Nizamabad, Telangana State M. Bhavya Manjari1*, C. Padma Veni2 and Venkata Rajkumar3 1Department of Home Science, Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Rudrur, Telangana, India 2Department of Agricultural Extension, Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Rudrur, Telangana, India 3Department of Horticulture, Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Rudrur, Telangana, India *Corresponding author ABSTRACT Women at Farm and Home contribute to economic growth in developing countries and clearly represent an untapped potential. When women adopt gender sensitive practices they can empower themselves, voice and represent decision making, provide business network, enhance access to market services and facilitate economics of scale. In this connection Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Rudrur conducted On Farm Trials on Farm and Home technologies for women in adopted villages to assess and refine for further demonstration. K e yw or ds For wider dissemination of these technologies and for the promotion of livelihood opportunity for the women, the present study was undertaken with the objectives 1. To Farm and Home Document consolidate feedback of beneficiaries on the results of On Farm Trials (OFT) on Technologies, Farm and Home technologies as Success Stories for wider dissemination and 2. To Livelihood Promotion, propose a strategy for market promotion of Farm and Home technologies as Sustainable Telangana State women livelihoods. Qualitative feedback was explored and consolidated from the year of Article Info inception of the OFT through Focus Group Discussions, frequent Monitoring Visits and Observations. -

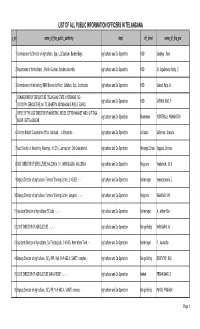

LIST of ALL PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICERS in TELANGANA S No Name of the Public Authority Dept Off Level Name of the Pio

LIST OF ALL PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICERS IN TELANGANA s_no name_of_the_public_authority dept off_level name_of_the_pio 1 Commissioner & Director of Agriculture, Opp. L.B.Stadium, BasheerBagh, - Agriculture and Co-Operation HOD Sandhya , Rani 2 Department of Horticulture, , Public Gurdens, Besides Assembly Agriculture and Co-Operation HOD Sri Jagadeswar Reddy, S 3 Commissioner of Marketing, BRKR Bhavan 1st floor, Saifabad, Opp. Secretariat Agriculture and Co-Operation HOD Samuel Raju, M COMMISSIONER OF SERICULTURE, TELANGANA STATE, HYDERABAD, 8-2- 4 Agriculture and Co-Operation HOD JAYAPAL RAO, P 293/82/PN/SERICULTURE, No. 72, BHARTIYA VIDYABHAVANS PUBLIC SCHOOL OFFICE OF THE ASST DIRECTOR OF MARKETING, BESIDE COTTON MARKET YARD, GUTTALA 5 Agriculture and Co-Operation Khammam VUDUTHALA, PADMAVATHI BAZAR, GUTTALA BAZAR 6 O/o the District Cooperative Office, Adilabad , , Collectorate , Agriculture and Co-Operation Adilabad Gaherwar, Sharada 7 Asst.Director of Marketing, Warangal, 4.1.234, Laxmipuram, Old Grain Market Agriculture and Co-Operation Warangal Urban Vuppala, Srinivas 8 ASST DIRECTOR OF SERICULTURE,NALGONDA, 1-1, MIRIYALGUDA, NALGONDA Agriculture and Co-Operation Nalgonda Venkatesh, Sri B 9 Deputy Director of Agriculture, Farmers Training Centre, 2-10-283, -, - Agriculture and Co-Operation Karimnagar Venkateswarlu, S. 10 Deputy Director of Agriculture, Farmers Training Centre, Suryapet, -, -, - Agriculture and Co-Operation Nalgonda RAMARAJU, KV 11 Assistant Director of Agriculture (BC Lab), -, -, - Agriculture and Co-Operation Karimnagar -

Impact of Success Cases Under RKVY Scheme at Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Rudrur, Nizamabad District, India

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2018) 7(10): 2661-2669 International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 7 Number 10 (2018) Journal homepage: http://www.ijcmas.com Review Article https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2018.710.309 Impact of Success Cases under RKVY Scheme at Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Rudrur, Nizamabad District, India C. Padma Veni1, Bandaru Venkata Rajkumar2, P. Vijay Kumar3, M. Bhavya Manjari4 and B. Kranthi Kumar5* 1(Agril. Extension) & Programme Coordinator, 2(Horticulture), 3(Plant Protection), 4(Home Science), 5(Crop Production), KVK, Rudrur, Telangana, India *Corresponding author ABSTRACT Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana (RKVY) is a State Plan Scheme of Additional Central Assistance launched during August, 2007 as a part of th the 11 Five year plan by the Government of India to achieve 4 % annual K e yw or ds growth in agriculture through development of agriculture and allied sectors. Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Rudrur was allocated fund Rs.22,00,000/- under Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana RKVY during 2014-15 for organising Field Testing and Popularizing (RKVY) , Annual Integrated Farming System Approach for the sustainable livelihoods where growth in Vanaraja Birds were distributed to 37 beneficiaries. Smt. Shameem, SHG agriculture member of KVK adopted village successfully implemented backyard Article Info poultry and started and rose to the occasion to earn Rs. 2000/- per month by 2016-17 after consuming by the family. KVK motivated the farmers on the Accepted: use of Raised bed planter, Sugarcane Ridger, Paddy straw Baler to promote 20 September 2018 Available Online: Farm mechanization in their fields by use of Success stories documented. -

Interactive Information Dissemination System

CHAPTER 15 Interactive Information Dissemination System AN ALTERNATIVE INFORMATION & COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGY MODEL TO MEET THE INFORMATION NEEDS OF INDIAN FARMERS ON ECO-FRIENDLY AGRICULTURE B. Savitha, Associate Professor and Interactive Information Dissemination System State (IIDS) Project Coordinator, Professor Jayashankar Telangana State Agricultural University (PJTSAU), India T. S. Anurag, Principal Research Scientist, IIDS Consortium Principal Investigator, and Chief Investigator of IIDS Platform Projects, Digital India Corporation (DIC), Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, New Delhi, India P. Punna Rao, Principal Scientist, IIDS Consortium Co-Principal Investigator, State IIDS Project Implementation Coordinator, Acharya N. G. Ranga Agricultural University (ANGRAU), India D. Raji Reddy, Director of Extension and Nodal IIDS Implementation Officer, PJTSAU, India M. Mahadeva, Research Associate, Digital India Corporation, New Delhi, India P. Sailu, Research Associate, Digital India Corporation, New Delhi, India List of Abbreviations AKPS Annapurna Krishi Prasaar Seva ANGRAU Acharya N. G. Ranga Agricultural University CAU Central Agricultural University DAATTCs District Agricultural Advisory and Transfer of Technology Centers DIC Digital India Corporation ICAR Indian Council of Agricultural Research ICT Information and Communication Technology IIDS Interactive Information Dissemination System IVRS Interactive Voice Response System KVKs Krishi Vigyan Kendras (Agriculture Science Centres) m4agriNEI Mobile Based Agro Advisory