Discourse Coalitions, Extractivist Politics, and the Northern Gateway Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Harper Casebook

— 1 — biogra HOW TO BECOME STEPHEN HARPER A step-by-step guide National Citizens Coalition • Quits Parliament in 1997 to become a vice- STEPHEN JOSEPH HARPER is the current president, then president, of the NCC. and 22nd Prime Minister of Canada. He has • Co-author, with Tom Flanagan, of “Our Benign been the Member of Parliament (MP) for the Dictatorship,” an opinion piece that calls for an Alberta riding of Calgary Southwest since alliance of Canada’s conservative parties, and 2002. includes praise for Conrad Black’s purchase of the Southam newspaper chain, as a needed counter • First minority government in 2006 to the “monophonically liberal and feminist” • Second minority government in 2008 approach of the previous management. • First majority government in May 2011 • Leads NCC in a legal battle to permit third-party advertising in elections. • Says “Canada is a Northern European welfare Early life and education state in the worst sense of the term, and very • Born and raised in Toronto, father an accountant proud of it,” in a 1997 speech on Canadian at Imperial Oil. identity to the Council for National Policy, a • Has a master’s degree in economics from the conservative American think-tank. University of Calgary. Canadian Alliance Political beginnings • Campaigns for leadership of Canadian Alliance: • Starts out as a Liberal, switches to Progressive argues for “parental rights” to use corporal Conservative, then to Reform. punishment against their children; describes • Runs, and loses, as Reform candidate in 1988 his potential support base as “similar to what federal election. George Bush tapped.” • Resigns as Reform policy chief in 1992; but runs, • Becomes Alliance leader: wins by-election in and wins, for Reform in 1993 federal election— Calgary Southwest; becomes Leader of the thanks to a $50,000 donation from the ultra Opposition in the House of Commons in May conservative National Citizens Coalition (NCC). -

The Rohingya Refugee Crisis

“ AN OCEAN OF MISERY ” THE ROHINGYA REFUGEE CRISIS Interim Report of the Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights The Honourable Wanda Elaine Thomas Bernard, Chair The Honourable Salma Ataullahjan, Deputy Chair The Honourable Jane Cordy, Deputy Chair FEBRUARY 2019 2 STANDING SENATE COMMITTEE ON HUMAN RIGHTS For more information please contact us: By email: [email protected] By mail: The Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights Senate, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1A 0A4 This report can be downloaded at: sencanada.ca The Senate is on Twitter: @SenateCA Follow the committee using the hashtag #RIDR Ce rapport est également offert en français “AN OCEAN OF MISERY”: THE ROHINGYA REFUGEE CRISIS 3 THE COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP The Honourable The Honourable The Honourable Wanda Thomas Bernard Salma Ataullahjan Jane Cordy Chair Deputy Chair Deputy Chair The Honourable Senatorsrs Yvonne Boyer Patrick Brazeau Nancy Hartling Thanh Hai Ngo Kim Pate Donald Neil Plett Ex-officio members of the committee: The Honourable Senator Peter Harder, P.C. (or Diane Bellemare) (or Grant Mitchell); Larry Smith (or Yonah Martin); Joseph Day (or Terry Mercer); Yuen Pau Woo (or Raymonde Saint-Germain) Other Senators who have participated in the study: The Honourable Senators Andreychuk, Coyle, Forest-Niesing, Martin, and Simons Parliamentary Information and Research Services, Library of Parliament: Erin Shaw, Jean-Philippe Duguay, and Alexandra Smith, Analysts Senate Committees Directorate: Barbara Reynolds, Clerk of the Committee Elda Donnelly, Administrative Assistant -

Senate Questionnaire Changing Subjects Now, We Want to Get

Senate Questionnaire Changing subjects now, we want to get people's views on the Canadian Senate. TRACKING 7. There are three broad choices in terms of the future of the Canadian Senate. Overall, which of the following would you say would be the best outcome? Would you say the Senate should be: Abolished Reformed Left as is 8. As you may have read, seen or heard, Canada’s Senate is back in the news. According to documents filed in court, the RCMP are investigating expense claims made by Senator Pamela Wallin, and Senators Patrick Brazeau and Mac Harb have been charged with one count each of fraud and breach of trust. Senator Mike Duffy faces 31 charges of fraud, breach of trust and bribery related to a $90,000 payment from the prime minister's former chief of staff to repay Duffy's ineligible expenses. The three trials are all expected to get underway later this year. How closely are you following these Senate issues? Are following it in the news, and discussing it with friends and family Seeing some media coverage, and having the odd conversation about it Just scanning the headlines Haven’t seen or heard anything about it 9. Whom do you trust the most to effectively deal with Senate issues? [Randomize top 3 choices] Conservative Party leader and Prime Minister Stephen Harper New Democratic Party leader Thomas Mulcair Liberal Party leader Justin Trudeau None of them Not sure 10. How much will the Senate debate be a factor for you in this year's federal election? (Please use the 1 to 10 scale below; you can choose any number that best reflects how much of a factor this is for you.) [1-10 Scale] Left hand label = 1 – Not a factor at all Right hand label = 10 – It’s the deciding factor . -

Identity Politicking: New Candidacies and Representations in Contemporary Canadian Politics

Identity Politicking: New Candidacies and Representations in Contemporary Canadian Politics by Teresa-Elise Maiolino A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology University of Toronto © Copyright by Teresa-Elise Maiolino 2017 Identity Politicking: New Candidacies and Representations in Contemporary Canadian Politics Teresa-Elise Maiolino Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology University of Toronto 2017 Abstract This dissertation centres on the candidacies and leaderships of three politicians—Justin Trudeau, Olivia Chow, and Kathleen Wynne. It examines the ways in which gender, race, sexuality, and other salient aspects of politicians’ identities are strategically negotiated and mobilized by politicians, political actors, the media, and the grassroots. The cases herein question the extent to which identity matters in Canadian electoral politics at the municipal, provincial, and federal levels, bridging sociological understandings of power and authority with feminist analyses of identity. The project engages broadly with qualitative methods—discourse analysis, media analysis, participant observation, and interviewing. The research contributes to understandings of: (1) the durability of masculinity in Canadian electoral politics; (2) dispositional requirements for leaders; (3) the compensatory labour that minority politicians perform; (4) alignments and allegiances between politicians and grassroots movements. The first case of the dissertation examines media coverage of a charity-boxing match between Liberal Member of Parliament Justin Trudeau and Conservative Canadian Senator Patrick Brazeau. It offers the concept recuperative gender strategies to describe how political leaders work to restore their public gender identities. The second case is focused on the candidacy of visible minority Toronto mayoral candidate, Olivia Chow. -

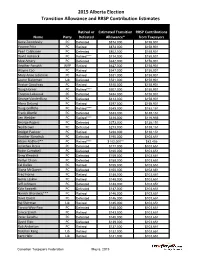

2015 Alberta Election Transition Allowance and RRSP Contribution Estimates

2015 Alberta Election Transition Allowance and RRSP Contribution Estimates Retired or Estimated Transition RRSP Contributions Name Party Defeated Allowance* from Taxpayers Gene Zwozdesky PC Defeated $874,000 $158,901 Yvonne Fritz PC Retired $873,000 $158,901 Pearl Calahasen PC Defeated $802,000 $158,901 David Hancock PC Retired**** $714,000 $158,901 Moe Amery PC Defeated $642,000 $158,901 Heather Forsyth WRP Retired $627,000 $158,901 Wayne Cao PC Retired $547,000 $158,901 Mary Anne Jablonski PC Retired $531,000 $158,901 Laurie Blakeman Lib Defeated $531,000 $158,901 Hector Goudreau PC Retired $515,000 $158,901 Doug Horner PC Retired**** $507,000 $158,901 Thomas Lukaszuk PC Defeated $484,000 $158,901 George VanderBurg PC Defeated $413,000 $158,901 Alana DeLong PC Retired $397,000 $158,901 Doug Griffiths PC Retired**** $349,000 $152,151 Frank Oberle PC Defeated $333,000 $138,151 Len Webber PC Retired**** $318,000 $116,956 George Rogers PC Defeated $273,000 $138,151 Neil Brown PC Defeated $273,000 $138,151 Bridget Pastoor PC Retired $238,000 $138,151 Heather Klimchuk PC Defeated $195,000 $103,651 Alison Redford** PC Retired**** $182,000** $82,456 Jonathan Denis PC Defeated $177,000 $103,651 Robin Campbell PC Defeated $160,000 $103,651 Greg Weadick PC Defeated $159,000 $103,651 Verlyn Olson PC Defeated $158,000 $103,651 Cal Dallas PC Retired $155,000 $103,651 Diana McQueen PC Defeated $150,000 $103,651 Fred Horne PC Retired $148,000 $103,651 Genia Leskiw PC Retired $148,000 $103,651 Jeff Johnson PC Defeated $148,000 $103,651 Kyle Fawcett -

Debates of the Senate

DEBATES OF THE SENATE 1st SESSION • 42nd PARLIAMENT • VOLUME 150 • NUMBER 201 OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Thursday, May 3, 2018 The Honourable GEORGE J. FUREY, Speaker CONTENTS (Daily index of proceedings appears at back of this issue). Debates Services: D’Arcy McPherson, National Press Building, Room 906, Tel. 613-995-5756 Publications Centre: Kim Laughren, National Press Building, Room 926, Tel. 613-947-0609 Published by the Senate Available on the Internet: http://www.parl.gc.ca 5394 THE SENATE Thursday, May 3, 2018 The Senate met at 1:30 p.m., the Speaker in the chair. While there are people who see pluralism as the problem, many are we who see it as the only answer to combating Prayers. ignorance, intolerance and hate. SENATORS’ STATEMENTS This is why I wish to congratulate His Highness the Aga Khan on 60 years of inspiration, hope and guidance toward a better and more pluralist world. HIS HIGHNESS THE AGA KHAN VISITOR IN THE GALLERY CONGRATULATIONS ON SIXTY YEARS AS THE IMAM OF THE SHIA ISMAILI MUSLIM COMMUNITY The Hon. the Speaker: Honourable senators, I wish to draw Hon. Peter Harder (Government Representative in the your attention to the presence in the gallery of Dr. Kyung-Ae Senate): Honourable senators, I rise today to congratulate His Park. She is the guest of the Honourable Senator Woo. Highness the Aga Khan on 60 years as the forty-ninth imam of the Shia Ismaili Muslim community and, as such, a direct On behalf of all honourable senators, I welcome you to the descendant of the Prophet Muhammad. -

Debates of the Senate

CANADA Debates of the Senate 2nd SESSION . 39th PARLIAMENT . VOLUME 144 . NUMBER 69 OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Thursday, June 12, 2008 ^ THE HONOURABLE NOËL A. KINSELLA SPEAKER CONTENTS (Daily index of proceedings appears at back of this issue). Debates and Publications: Chambers Building, Room 943, Tel. 996-0193 Published by the Senate Available from PWGSC ± Publishing and Depository Services, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0S5. Also available on the Internet: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1488 THE SENATE Thursday, June 12, 2008 The Senate met at 1:30 p.m., the Speaker in the chair. Hon. Joan Cook: Honourable senators, I would also like to express my sincere gratitude to the Director of Human Resources, Prayers. Ann Dufour, for her many years of loyal service. Under the leadership of the Clerk of Senate and Clerk of the SENATORS' STATEMENTS Parliaments, Mr. Paul Bélisle, Ann thrived in her role by successfully leading a number of significant initiatives. Her immeasurable contributions will continue to help the Senate in MS. ANN DUFOUR meeting future human resources challenges. Thanks to her vision, we are prepared to deal with changing demographics and the increasing competition to recruit and retain the best and TRIBUTES ON RETIREMENT AS DIRECTOR the brightest. OF HUMAN RESOURCES DIRECTORATE Needless to say, Ms. Dufour's retirement will leave a gap in this Hon. Terry Stratton: Honourable senators, please join me in fine institution and finding a replacement will not be an easy feat. congratulating Ms. Ann Dufour on her upcoming retirement. Ann will be leaving her position as Director of Human Resources Ann Dufour has earned our highest esteem and she will be in July. -

Legislative Assembly of Alberta the 27Th Legislature First Session

Legislative Assembly of Alberta The 27th Legislature First Session Standing Committee on Private Bills Tuesday, May 13, 2008 9:04 a.m. Transcript No. 27-1-1 Legislative Assembly of Alberta The 27th Legislature First Session Standing Committee on Private Bills Brown, Dr. Neil, QC, Calgary-Nose Hill (PC), Chair Woo-Paw, Teresa, Calgary-Mackay (PC), Deputy Chair Allred, Ken, St. Albert (PC) Amery, Moe, Calgary-East (PC) Anderson, Rob, Airdrie-Chestermere (PC) Benito, Carl, Edmonton-Mill Woods (PC) Boutilier, Guy C., Fort McMurray-Wood Buffalo (PC) Calahasen, Pearl, Lesser Slave Lake (PC) Campbell, Robin, West Yellowhead (PC) Doerksen, Arno, Strathmore-Brooks (PC) Elniski, Doug, Edmonton-Calder (PC) Fawcett, Kyle, Calgary-North Hill (PC) Forsyth, Heather, Calgary-Fish Creek (PC) Jacobs, Broyce, Cardston-Taber-Warner (PC) MacDonald, Hugh, Edmonton-Gold Bar (L) McQueen, Diana, Drayton Valley-Calmar (PC) Olson, Verlyn, QC, Wetaskiwin-Camrose (PC) Quest, Dave, Strathcona (PC) Sandhu, Peter, Edmonton-Manning (PC) Sarich, Janice, Edmonton-Decore (PC) Swann, Dr. David, Calgary-Mountain View (L) Bill Pr. 1 Sponsor Lukaszuk, Thomas A., Edmonton-Castle Downs (PC) Support Staff Robert H. Reynolds, QC Senior Parliamentary Counsel Shannon Dean Senior Parliamentary Counsel Florence Marston Administrative Assistant Liz Sim Managing Editor of Alberta Hansard Transcript produced by Alberta Hansard May 13, 2008 Private Bills PB-1 9:04 a.m. Tuesday, May 13, 2008 The Chair: Since it’s the first meeting and the first time for some of Title: Tuesday, May 13, 2008 PB you on the committee, I thought it might be useful to give a brief [Dr. Brown in the chair] overview, but before we do that, I will go through the approval of the agenda as circulated. -

Alberta Hansard

Province of Alberta The 28th Legislature Second Session Alberta Hansard Monday afternoon, May 5, 2014 Issue 24 The Honourable Gene Zwozdesky, Speaker Legislative Assembly of Alberta The 28th Legislature Second Session Zwozdesky, Hon. Gene, Edmonton-Mill Creek (PC), Speaker Rogers, George, Leduc-Beaumont (PC), Deputy Speaker and Chair of Committees Kalagian-Jablonski, Mary Anne, Red Deer-North (PC), Deputy Chair of Committees Allen, Mike, Fort McMurray-Wood Buffalo (Ind) Kennedy-Glans, Donna, QC, Calgary-Varsity (Ind) Amery, Moe, Calgary-East (PC) Khan, Stephen, St. Albert (PC) Anderson, Rob, Airdrie (W), Klimchuk, Hon. Heather, Edmonton-Glenora (PC) Official Opposition House Leader Kubinec, Maureen, Barrhead-Morinville-Westlock (PC) Anglin, Joe, Rimbey-Rocky Mountain House-Sundre (W) Lemke, Ken, Stony Plain (PC) Barnes, Drew, Cypress-Medicine Hat (W) Leskiw, Genia, Bonnyville-Cold Lake (PC) Bhardwaj, Hon. Naresh, Edmonton-Ellerslie (PC) Luan, Jason, Calgary-Hawkwood (PC) Bhullar, Hon. Manmeet Singh, Calgary-Greenway (PC) Lukaszuk, Hon. Thomas A., Edmonton-Castle Downs (PC) Bikman, Gary, Cardston-Taber-Warner (W) Mason, Brian, Edmonton-Highlands-Norwood (ND), Bilous, Deron, Edmonton-Beverly-Clareview (ND) Leader of the New Democrat Opposition Blakeman, Laurie, Edmonton-Centre (AL), McAllister, Bruce, Chestermere-Rocky View (W) Liberal Opposition House Leader McDonald, Everett, Grande Prairie-Smoky (PC) Brown, Dr. Neil, QC, Calgary-Mackay-Nose Hill (PC) McIver, Hon. Ric, Calgary-Hays (PC) Calahasen, Pearl, Lesser Slave Lake (PC) McQueen, Hon. Diana, Drayton Valley-Devon (PC) Campbell, Hon. Robin, West Yellowhead (PC), Notley, Rachel, Edmonton-Strathcona (ND), Government House Leader New Democrat Opposition House Leader Cao, Wayne C.N., Calgary-Fort (PC) Oberle, Hon. Frank, Peace River (PC), Deputy Government House Leader Casey, Ron, Banff-Cochrane (PC) Olesen, Cathy, Sherwood Park (PC) Cusanelli, Christine, Calgary-Currie (PC) Olson, Hon. -

Suggested Messages for Senators Regarding Bill C-262

Suggested Messages for Senators Regarding Bill C-262 Friends! Bill C-262 is an act asking “... the Government of Canada to take all measures necessary to ensure that the laws of Canada are in harmony with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.” Read the complete text of Bill C-262 Because of the amazing grassroots advocacy of at https://goo.gl/mWTFLh Indigenous peoples, churches and social justice organizations, Bill C-262 has passed 3rd reading in the For more info about the House of Commons and is now up for debate in the UN Declaration and C-262 see Senate. www.declarationcoalition.com Below are some suggested messages for handwritten postcards urging Senators to support Bill C-262. Pick one that resonates, or feel free to craft your own. Use language that is positive and respectful, as it will garner more ears to hear. Bill C-262 can change Canada’s future and move us toward respectful relations with Indigenous nations. I urge you to support Bill C-262, “An Act to ensure that the laws of Canada are in harmony with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.” The Truth and Reconciliation Commission has stated that the adoption of the Declaration is foundational to any genuine reconciliation in Canada. Bill C-262 can make that happen. Please support this “Act to ensure that the laws of Canada are in harmony with the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.” I pray for the federal government, as I pray for myself: that we would have the courage to seek justice and do the hard work required to repair the damage of colonialism. -

Premier Promotes Verlyn Olson and Greg Weadick to Cabinet Cal Dallas Becomes the New Parliamentary Assistant to Finance

February 17, 2011 Premier promotes Verlyn Olson and Greg Weadick to cabinet Cal Dallas becomes the new Parliamentary Assistant to Finance Edmonton... Premier Ed Stelmach announced today that Wetaskiwin-Camrose MLA Verlyn Olson, QC, has been named Minister of Justice and Attorney General, and Lethbridge West MLA Greg Weadick has been named Minister of Advanced Education and Technology. “I’m pleased to welcome Verlyn and Greg to the cabinet table,” said Premier Stelmach. “Verlyn and Greg bring the necessary talent and experience - Greg as a parliamentary assistant and Verlyn as a long-time member of the bar - to complete our cabinet team. Our cabinet will continue to provide the steady leadership required right now to continue building a better Alberta.” Premier Stelmach also named a new Parliamentary Assistant to the Minister of Finance and Enterprise. “I’m pleased that Red Deer South MLA Cal Dallas, who had been serving as the Parliamentary Assistant in Environment, will take over this important role and work closely with Finance Minister Lloyd Snelgrove,” said the Premier. Premier Stelmach also announced changes to committee memberships. Joining the Agenda and Priorities Committee are Sustainable Resource Development Minister Mel Knight, Children and Youth Services Minister Yvonne Fritz and Agriculture and Rural Development Minister Jack Hayden. New members of Treasury Board are Len Webber, Minister of Aboriginal Relations, Heather Klimchuk, Minister of Service Alberta, and Naresh Bhardwaj, MLA for Edmonton-Ellerslie. The new Cabinet members will be sworn in Friday, February 18 at 8:30 a.m. at Government House. Lloyd Snelgrove was sworn in as Minister of Finance and Enterprise on January 31. -

Alberta Hansard

Province of Alberta The 28th Legislature Third Session Alberta Hansard Tuesday afternoon, March 17, 2015 Issue 21a The Honourable Gene Zwozdesky, Speaker Legislative Assembly of Alberta The 28th Legislature Third Session Zwozdesky, Hon. Gene, Edmonton-Mill Creek (PC), Speaker Rogers, George, Leduc-Beaumont (PC), Deputy Speaker and Chair of Committees Jablonski, Mary Anne, Red Deer-North (PC), Deputy Chair of Committees Allen, Mike, Fort McMurray-Wood Buffalo (PC) Kubinec, Hon. Maureen, Barrhead-Morinville-Westlock (PC) Amery, Moe, Calgary-East (PC) Lemke, Ken, Stony Plain (PC), Anderson, Rob, Airdrie (PC) Deputy Government Whip Anglin, Joe, Rimbey-Rocky Mountain House-Sundre (Ind) Leskiw, Genia, Bonnyville-Cold Lake (PC) Barnes, Drew, Cypress-Medicine Hat (W) Luan, Jason, Calgary-Hawkwood (PC) Bhardwaj, Naresh, Edmonton-Ellerslie (PC) Lukaszuk, Thomas A., Edmonton-Castle Downs (PC) Bhullar, Hon. Manmeet Singh, Calgary-Greenway (PC) Mandel, Hon. Stephen, Edmonton-Whitemud (PC) Bikman, Gary, Cardston-Taber-Warner (PC) Mason, Brian, Edmonton-Highlands-Norwood (ND) Bilous, Deron, Edmonton-Beverly-Clareview (ND), McAllister, Bruce, Chestermere-Rocky View (PC) New Democrat Opposition Whip McDonald, Hon. Everett, Grande Prairie-Smoky (PC) Blakeman, Laurie, Edmonton-Centre (AL), McIver, Hon. Ric, Calgary-Hays (PC) Liberal Opposition House Leader McQueen, Hon. Diana, Drayton Valley-Devon (PC) Brown, Dr. Neil, QC, Calgary-Mackay-Nose Hill (PC) Notley, Rachel, Edmonton-Strathcona (ND), Calahasen, Pearl, Lesser Slave Lake (PC) Leader of the New Democrat Opposition Campbell, Hon. Robin, West Yellowhead (PC) Oberle, Hon. Frank, Peace River (PC), Cao, Wayne C.N., Calgary-Fort (PC) Deputy Government House Leader Casey, Ron, Banff-Cochrane (PC) Olesen, Cathy, Sherwood Park (PC) Cusanelli, Christine, Calgary-Currie (PC) Olson, Hon.