Matter of ORE-, 28 I&N Dec

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Independent Cinema 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

AMERICAN INDEPENDENT CINEMA 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Geoff King | 9780253218261 | | | | | American Independent Cinema 1st edition PDF Book About this product. Hollywood was producing these three different classes of feature films by means of three different types of producers. The Suburbs. Skip to main content. Further information: Sundance Institute. In , the same year that United Artists, bought out by MGM, ceased to exist as a venue for independent filmmakers, Sterling Van Wagenen left the film festival to help found the Sundance Institute with Robert Redford. While the kinds of films produced by Poverty Row studios only grew in popularity, they would eventually become increasingly available both from major production companies and from independent producers who no longer needed to rely on a studio's ability to package and release their work. Yannis Tzioumakis. Seeing Lynch as a fellow studio convert, George Lucas , a fan of Eraserhead and now the darling of the studios, offered Lynch the opportunity to direct his next Star Wars sequel, Return of the Jedi Rick marked it as to-read Jan 05, This change would further widen the divide between commercial and non-commercial films. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Until his so-called "retirement" as a director in he continued to produce films even after this date he would produce up to seven movies a year, matching and often exceeding the five-per-year schedule that the executives at United Artists had once thought impossible. Very few of these filmmakers ever independently financed or independently released a film of their own, or ever worked on an independently financed production during the height of the generation's influence. -

Representations of Mental Illness in Women in Post-Classical Hollywood

FRAMING FEMININITY AS INSANITY: REPRESENTATIONS OF MENTAL ILLNESS IN WOMEN IN POST-CLASSICAL HOLLYWOOD Kelly Kretschmar, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Harry M. Benshoff, Major Professor Sandra Larke-Walsh, Committee Member Debra Mollen, Committee Member Ben Levin, Program Coordinator Alan B. Albarran, Chair of the Department of Radio, Television and Film Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Kretschmar, Kelly, Framing Femininity as Insanity: Representations of Mental Illness in Women in Post-Classical Hollywood. Master of Arts (Radio, Television, and Film), May 2007, 94 pp., references, 69 titles. From the socially conservative 1950s to the permissive 1970s, this project explores the ways in which insanity in women has been linked to their femininity and the expression or repression of their sexuality. An analysis of films from Hollywood’s post-classical period (The Three Faces of Eve (1957), Lizzie (1957), Lilith (1964), Repulsion (1965), Images (1972) and 3 Women (1977)) demonstrates the societal tendency to label a woman’s behavior as mad when it does not fit within the patriarchal mold of how a woman should behave. In addition to discussing the social changes and diagnostic trends in the mental health profession that define “appropriate” female behavior, each chapter also traces how the decline of the studio system and rise of the individual filmmaker impacted the films’ ideologies with regard to mental illness and femininity. Copyright 2007 by Kelly Kretschmar ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 1 Historical Perspective ........................................................................ 5 Women and Mental Illness in Classical Hollywood ............................... -

Not for Publication United States Court of Appeals

FILED NOT FOR PUBLICATION OCT 30 2013 MOLLY C. DWYER, CLERK UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS U.S. COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT WARNER BROS ENTERTAINMENT, No. 13-55352 INC., a Delaware corporation; et al., D.C. No. 2:12-cv-09547-PSG-CW Plaintiffs - Appellees, v. MEMORANDUM* THE GLOBAL ASYLUM, INC., a California corporation, DBA The Asylum, Defendant - Appellant. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Central District of California Philip S. Gutierrez, District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted October 7, 2013 Pasadena, California Before: FERNANDEZ, PAEZ, and HURWITZ, Circuit Judges. Defendant The Global Asylum, Inc. (“Asylum”) appeals the district court’s order granting Plaintiffs Warner Brothers Entertainment, Inc., New Line Productions, Inc., Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios, Inc., Saul Zaentz Company, and * This disposition is not appropriate for publication and is not precedent except as provided by 9th Cir. R. 36-3. New Line Cinema, LLC’s (collectively “Studios”) motion for a preliminary injunction. 1. “A plaintiff seeking a preliminary injunction must establish that he is likely to succeed on the merits, that he is likely to suffer irreparable harm in the absence of preliminary relief, that the balance of equities tips in his favor, and that an injunction is in the public interest.” Winter v. Natural Res. Def. Council, Inc., 555 U.S. 7, 20 (2008). The district court found that all four Winter elements were met. 2. On appeal, Asylum challenges only the district court’s ruling that the Studios are likely to succeed on their trademark infringement claim under 15 U.S.C. -

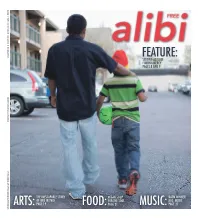

Arts: Food: Feature

FEATURE: VOLUME 28 | ISSUE 15 | APRIL 11-17, 2019 | FREE 2019 | ISSUE 15 APRIL 11-17, 28 VOLUME SEEKING ASYLUM FINDING MERCY PAGES 8 AND 9 PHOTO BY ERIC WILLIAMS BY PHOTO THE INESCAPABLE STORY VEGAN SOUP BoBM WINNER OF ONE IN TWO FOR THE SOUL M.O. MUSIC ARTS: PAGE 19 FOOD: PAGE 21 MUSIC: PAGE 27 STIRRING THE MELTING POT SINCE 1992 SINCE 1992 POT THE MELTING STIRRING [ 2] WEEKLY ALIBI APRIL 11-17, 2019 APRIL 11-17, 2019 WEEKLY ALIBI [3] alibi VOLUME 28 | ISSUE 15 | APRIL 11-17, 2019 EDITORIAL MANAGING EDITOR/ FILM EDITOR: Devin D. O’Leary (ext. 230) [email protected] MUSIC EDITOR/NEWS EDITOR: August March (ext. 245) [email protected] FOOD EDITOR: Email letters, including author’s name, mailing address and daytime phone number to [email protected]. Dan Pennington (Ext. 255) [email protected] Letters can also be mailed to P.O. Box 81, Albuquerque, N.M., 87103. Letters—including comments posted ARTS AND LIT.EDITOR: Clarke Condé [email protected] on alibi.com—may be published in any medium and edited for length and clarity; owing to the volume of COPY EDITOR: correspondence, we regrettably can’t respond to every letter. Samantha Carrillo (ext. 223) [email protected] CALENDARS EDITOR: Ashli Kesali [email protected] STAFF WRITER: Joshua Lee (ext. 243) [email protected] Methane Goes Bust the gas pump. Why should citizens have to SOCIAL MEDIA COORDINATOR: Samantha Carrillo (ext. 223) [email protected] have lung-destroying toxics forming in New CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: Dear Editor, Mexico’s air? Those are fugitive emissions Robin Babb, Rob Brezsny, Carolyn Carlson, Samantha On “Methane Goes Boom!” [Alibi v28 i14]: Carrillo, Desmond Fox, Maggie Grimason, Steven Luthy, going on for decades. -

Video 108 Media Corp 9 Story A&E Networks A24 All Channel Films

Video 108 Media Corp 9 Story A&E Networks A24 All Channel Films Alliance Entertainment American Cinema Inspires American Public Television Ammo Content Astrolab Motion Bayview Entertainment BBC Bell Marker Bennett-Watt Entertainment BidSlate Bleecker Street Media Blue Fox Entertainment Blue Ridge Holdings Blue Socks Media BluEvo Bold and the Beautiful Brain Power Studio Breaking Glass BroadGreen Caracol CBC Cheng Cheng Films Christiano Film Group Cinedigm Cinedigm Canada Cinema Libre Studio CJ Entertainment Collective Eye Films Comedy Dynamics Content Media Corp Culver Digital Distribution DBM Films Deep C Digital DHX Media (Cookie Jar) Digital Media Rights Dino Lingo Disney Studios Distrib Films US Dreamscape Media Echelon Studios Eco Dox Education 2000 Electric Entertainment Engine 15 eOne Films Canada Epic Pictures Epoch Entertainment Equator Creative Media Everyday ASL Productions Fashion News World Inc Film Buff Film Chest Film Ideas Film Movement Film UA Group FilmRise Filmworks Entertainment First Run Features Fit for Life Freestyle Digital Media Gaiam Giant Interactive Global Genesis Group Global Media Globe Edutainment GoDigital Inc. Good Deed Entertainment GPC Films Grasshopper Films Gravitas Ventures Green Apple Green Planet Films Growing Minds Gunpowder & Sky Distribution HG Distribution Icarus Films IMUSTI INC Inception Media Group Indie Rights Indigenius Intelecom Janson Media Juice International KDMG Kew Media Group KimStim Kino Lorber Kinonation Koan Inc. Language Tree Legend Films Lego Leomark Studios Level 33 Entertainment -

– Unsinn Im Genre-Film Das Spiel Mit Der Medienkompetenz Im Mockbuster SHARKNADO

kids+media 1/18 Populär – Unsinn im Genre-Film Das Spiel mit der Medienkompetenz im Mockbuster SHARKNADO Von Natalie Borsy Man stelle sich diesen Unsinn vor: Gebäude und ein Riesenrad, welche man vielleicht von Bildern des bekannten Piers von Santa Monica wiedererkennt, stürzen vor der Kulisse blutrot schäumender Wellen ein. Ein Tornado fegt durch das Meer und reisst den Schutt des Infernos mit, doch aus ihm heraus brechen ... Haie. Die blutverschmierten, von scharfen Zähnen bewehrten, aufgerissenen Mäuler von Haien werden vom Titel des Plakats komplementiert, welcher grell verkündet: „SHARKNADO. ENOUGH SAID!“ Abb. 1: SHARKNADO Werbeposter Tatsächlich waren keine weiteren Worte oder Erklärungen vonnöten, um einen beispiellosen Inter- nethype auszulösen, als die für Low-Budget-Filme bekannt gewordene Filmproduktionsgesellschaft The Asylum 2013 dieses Plakat veröffentlichte (siehe Abb. 1).1 The Asylum hat neben weiteren ab- surden Produktionen wie MEGA SHARK VS. GIANT OCTOPUS (2009), 2-HEADED SHARK ATTACK (2012) und ABRAHAM LINCOLN VS. ZOMBIES (2012) mit SHARKNADO erfolgreich die Nische des Mockbus- ters2 erobert. Nicht zuletzt erfährt SHARKNADO aufgrund von Bewertungen wie jener von Rotten Tomatoes, welche den Film als „[p]roudly, shamelessly, and gloriously brainless“ und „so bad it’s good“3 anpreist, eine Reihe von Fortsetzungen: Seit seiner ersten Ausstrahlung auf dem Sender Syfy 1 Vgl. Lázár 2015, S. 257. 2 Csaba Lázár definiert den Mockbuster als „[b]illige Quasi-Kopien erfolgreicher Hollywood-Filme mit bewusst ähnlich gewählten Titeln, qualitativ allerdings meilenweit entfernt“ (2015, S. 256). 3 https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/sharknado_2013/. Herausgegeben vom Institut für Sozialanthropologie und Empirische Kulturwissenschaft (ISEK) der Universität Zürich 53 kids+media 1/18 Populär 2013 toben jedes Jahr neue Sharknados in den US-Metropolen der Fernseherfilme und im Juli 2016 hat SHARKNADO 4: THE 4TH AWAKENS es sofort in die Kinos der Vereinigten Staaten geschafft. -

Madness, Sex and the Asylum in American Horror Story

“A Convenient Place for Inconvenient People”: madness, sex and the asylum in American Horror Story EARLE, Harriet <http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7354-3733> Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/15245/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version EARLE, Harriet (2017). “A Convenient Place for Inconvenient People”: madness, sex and the asylum in American Horror Story. The Journal of Popular Culture, 50 (2), 259-275. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk 1 ‘A Convenient Place for Inconvenient People’: Madness, Sex and the Asylum in American Horror Story The asylum in contemporary American visual culture offers a site of representation that is rich in possibilities for cultural and social comment, using an image of madness1 that plays with modern-day conceptions of mental illness to connote and critique contemporary social insecurities and fears. Although the asylum fell out of favour, due in part to negative connotations and a restructuring of in-patient care in the latter half of the twentieth century – such institutions are more commonly referred to as psychiatric hospitals or (sometimes) the euphemistic “residential assessment units” – the term persists in common parlance, and the physical space is a frequent location in horror and other fictional stories. The fictional asylum provides a theatrical location onto which the contemporary idea of madness can be imprinted and into which a cast of characters can be placed so as to re-enact our fears and misconceptions. -

Jack Davenport

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Jack Davenport Talent Representation Telephone Christian Hodell +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected], Address [email protected], Hamilton Hodell, [email protected] 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Television Title Role Director Production Company CALL MY AGENT Jonathan John Morton Bron Studios THE MORNING SHOW Jason Craig Various Apple TV+ WHY WOMEN KILL Karl Grove Various CBS NEXT OF KIN Guy Grayling Justin Chadwick Mammoth Screen/ITV PROTOTYPE Edward Conway Juan Carlos Fresnadillo Silver Screen Pictures/Syfy UNTITLED SARAH SILVERMAN PROJECT Blake Charlie McDowell HBO LIFE IN SQUARES David 'Bunny' Garnett Simon Kaijser BBC BREATHLESS Otto Powell Paul Unwin ITV THE GOOD WIFE Series 5 Frank Asher Matt Shankman CBS ABC Studios/Sony Pictures SEA OF FIRE Marty Kesowich Allison Liddi-Brown Television SMASH Series 1 & 2 Derek Wills Various NBC FLASH FORWARD Lloyd Simcoe David Goyer Touchstone Television SWINGTOWN Bruce Miller Alan Paul CBS Paramount THIS LIFE + 10 Miles Joe Ahearne World Productions/BBC MARY BRYANT Clarke Peter Andrikidis Granada MISS MARPLE: THE BODY IN THE LIBRARY Harper Andy Wilson ITV EROICA Prince Lobkovitz Simon Cellan Jones BBC COUPLING Winner of Best TV Comedy, British Comedy Awards 2003 Steve Martin Dennis BBC THE REAL JANE AUSTEN Henry Austen Nicky Pattison BBC4 DICKENS Charley Dickens Chris Granlund BBC THE ASYLUM Nick Copus FictionLab THE WYVERN MYSTERY [TV movie] Harry Fairfield Alex Pillai BBC ULTRA-VIOLET Det. Michael Colefield Joe Ahearne -

AFM 2018 Show Directory

AMERICAN FILM MARKET® SHOW DIRECTORY 2018 2018 General Information 5 Hours Lounges Internet Shuttles Screenings Theatres Hotel Restaurants Parking Hotel Directory Programs 15 Conferences Roundtables Writers Workshops Spotlight Events Exhibitors 19 Floor Plans 55 Independent Film & Television Alliance 73 Santa Monica Map 79 1 SUPERIOR COMFORT REPRESENTING PRODUCERS AND DISTRIBUTORS WORLDWIDE ON SELECT INTERNATIONAL FLIGHTS. Dear Colleagues, CHOOSE DELTA PREMIUM SELECT. We are here again, beachside, for the 2018 American Film Market. Enjoy a quiet cabin with wider, adjustable seats, While this wonderful location is the same, every AFM is different dedicated service, and delightful meals. because of you. The true universality of film is evident from the moment you enter the AFM doors. Our industry is built on a foundation of relationships, collaboration, and knowledge. The premieres, projects, and deals will be in the headlines, but the personal stories of connections made, information gathered, and ideas shared are the hidden value of AFM. This is a pure market — created as a hub for serious stakeholders to gather. This year we have enhanced the AFM environment and made access to the Loews exclusive to our official global participants. The conversations happening within the AFM offices and hallways will echo to AFM attendees through our expanded programming of Conferences, Roundtables, Workshops, and Spotlight Events. We will kick off an exploration of where the industry is headed with a new Global Perspective Conference. Throughout the week, forecasts for the future and advice on how to best navigate our industry will be offered through the lens of 150 international industry experts, decision makers, and academics. -

Buzz Bombs: the Room, Snakes on a Plane and Cult Audiences in the Internet Era

Buzz Bombs: The Room, Snakes on a Plane and Cult Audiences in the Internet Era Derek Godin A Thesis In The Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada July 2013 © Derek Godin, 2013 ii CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Derek Godin Entitled: Buzz Bombs: The Room, Snakes on a Plane and Cult Audiences in the Internet Era and submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: ________________________ Chair Dr. Ernest Mathijs______________ Examiner Dr. Marc Steinberg______________ Examiner Dr. Haidee Wasson______________ Supervisor Approved by _________________________ Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director ____________ 2013 _________________________ Dean of Faculty iii ABSTRACT Buzz Bombs: The Room, Snakes on a Plane and Cult Audiences in the Internet Era Derek Godin This thesis will chart the lives of two films released in the 21st century that had audiences identifiable as cult: The Room (Tommy Wiseau, 2003) and Snakes on a Plane (David R. Ellis, 2006). It will cover each film's conception, production history, release, reception and ongoing half-life. But special focus will be given in each case to the online activities of the fans, be it creating fan art or spreading word of these particular films. Specifically, this thesis will discuss online fan activity pertaining to both films, and how each film and fan activities related to each fit in the context of fan studies and cult studies. -

TCC Bruna Lionço.Pdf (11.26Mb)

ÁREA DO CONHECIMENTO DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS HABILITAÇÃO EM PUBLICIDADE E PROPAGANDA BRUNA LIONÇO MOCKBUSTER NA PRODUÇÃO CINEMATOGRÁFICA: A IMITAÇÃO É A FORMA MAIS SINCERA DE ELOGIO? Caxias do Sul 2019 UNIVERSIDADE DE CAXIAS DO SUL ÁREA DO CONHECIMENTO DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS CURSO DE COMUNICAÇÃO SOCIAL HABILITAÇÃO EM PUBLICIDADE E PROPAGANDA BRUNA LIONÇO MOCKBUSTER NA PRODUÇÃO CINEMATOGRÁFICA: A IMITAÇÃO É A FORMA MAIS SINCERA DE ELOGIO? Monografia do curso de Comunicação Social, habilitação em Publicidade e Propaganda da Universidade de Caxias do Sul, apresentada como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Bacharel. Orientador (a): Prof. Dr. Ivana Almeida da Silva Caxias do Sul 2019 2 BRUNA LIONÇO MOCKBUSTER NA PRODUÇÃO CINEMATOGRÁFICA: A IMITAÇÃO É A FORMA MAIS SINCERA DE ELOGIO? Monografia do curso de Comunicação Social, habilitação em Publicidade e Propaganda da Universidade de Caxias do Sul, apresentada como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Bacharel. Aprovado em: __/__/____ Banca Examinadora _____________________________________ Prof. Dr. Ivana Almeida da Silva Universidade de Caxias do Sul – UCS _____________________________________ Prof. Me. Carlos Antônio de Andrade Arnt Universidade de Caxias do Sul – UCS _____________________________________ Prof. Me. Flóra Simon da Silva Universidade de Caxias do Sul – UCS 3 AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço o apoio de toda a minha família, em especial aos meus queridos pais e irmãos, que de diversas formas me auxiliaram durante esta jornada e nunca deixaram de acreditar em mim. Agradeço também aos meus amigos e colegas que estiveram do meu lado ao longo desta caminhada e tornaram mais alegre esta importante fase da minha vida acadêmica. Agradeço imensamente à orientadora deste trabalho, Prof. -

LA Intensive 2015 Schedule FINAL

2015 L.A. INTENSIVE SCHEDULE Saturday, August 8 4:00 p.m. Check-in at UCLA 6:00 p.m. Orientation meeting 6:30 p.m. Dinner at UCLA Roundtable: Welcome to Hollywood Michael Bremer, Program Director Kelsey Murphy, Student Programs Coordinator 7:30 p.m. Walking tour of Westwood Village 8:00 p.m. Dessert at Diddy Riece, Westwood Village Sunday, August 9 8:00 a.m. Breakfast at UCLA 9:15 a.m. Depart UCLA for driving tour of Los Angeles 9:30 a.m. Westwood Cemetery, Santa Monica, Venice 12:00 p.m. Lunch at Farmer’s Market, The Grove 1:00 p.m. Driving tour continues: Bronson Canyon “Bat-cave,” Hollywood Sign, Hollywood Walk of Fame, Grauman’s Chinese Theater, Greystone Mansion 5:30 p.m. Return to UCLA 6:30 p.m. Dinner at UCLA Roundtable: Pitch Workshop Pt. I Harrison Reiner, Producer, Writer, Director, Pitch Expert Monday, August 10 8:00 a.m. Breakfast at UCLA 9:00 a.m. Depart UCLA - Tour Beverly Hills and Century City 10:30am Private Tour: Sony Pictures Animation, Culver City Founded in 2002, S.P.A. is an American animation company owned by Sony Pictures Entertainment. It works closely with Sony Pictures Imageworks, which handles digital production. The studio’s first feature film, Open Season, was released in 2006. Other work includes The Smurfs film series and Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs. 1:00 p.m. Lunch at Sony Studios Commissary Maria Marill, Executive VP, Production Services 2:30 p.m. Private Tour: Sony Pictures Post Production, Culver City Sony Pictures Post Production Facilities was built for filmmakers by postproduction professionals and is one of the largest, full service postproduction facilities in Hollywood.