Battersea Bridge Road to York Road

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greater London Authority

Consumer Expenditure and Comparison Goods Retail Floorspace Need in London March 2009 Consumer Expenditure and Comparison Goods Retail Floorspace Need in London A report by Experian for the Greater London Authority March 2009 copyright Greater London Authority March 2009 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4100 minicom 020 7983 4458 ISBN 978 1 84781 227 8 This publication is printed on recycled paper Experian - Business Strategies Cardinal Place 6th Floor 80 Victoria Street London SW1E 5JL T: +44 (0) 207 746 8255 F: +44 (0) 207 746 8277 This project was funded by the Greater London Authority and the London Development Agency. The views expressed in this report are those of Experian Business Strategies and do not necessarily represent those of the Greater London Authority or the London Development Agency. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................................................... 5 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................... 5 CONSUMER EXPENDITURE PROJECTIONS .................................................................................... 6 CURRENT COMPARISON FLOORSPACE PROVISION ....................................................................... 9 RETAIL CENTRE TURNOVER........................................................................................................ 9 COMPARISON GOODS FLOORSPACE REQUIREMENTS -

Charles Roberts Autograph Letters Collection MC.100

Charles Roberts Autograph Letters collection MC.100 Last updated on January 06, 2021. Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections Charles Roberts Autograph Letters collection Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................7 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 9 110.American poets................................................................................................................................. 9 115.British poets.................................................................................................................................... 16 120.Dramatists........................................................................................................................................23 130.American prose writers...................................................................................................................25 135.British Prose Writers...................................................................................................................... 33 140.American -

The Diaries of Mariam Davis Sidebottom Houchens

THE DIARIES OF MARIAM DAVIS SIDEBOTTOM HOUCHENS VOLUME 7 MAY 15, 1948-JUNE 9, 1957 Copyright 2015 © David P. Houchens TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 7 Page Preface i Table of Contents ii Book 69- Saturday, May 15, 1948-Wednesday, July 7, 1948 1 Book 70- Thursday, July 8, 1948-Wednesday, September 8, 1948 25 Book 71- Thursday, September 9, 1948-Saturday, December 11, 1948 29 Book72- Sunday, December 12, 1948-Wednesday, January 26, 1949 32 Book 73- Thursday, January 27, 1949-Wednesday, February 23, 1949 46 Book 74- Thursday, February 24, 1949-Saturday, March 26, 1949 51 Book 75- Sunday, March 27, 1949-Saturday, April 23, 1949 55 Book 76- Sunday, April 24, 1949-Thursday, Friday July 1, 1949 61 Book 77- Saturday, July 2, 1949-Tuesday, August 30, 1949 68 Book 78- Wednesday, August 31, 1949-Tuesday, November 22, 1949 78 Book79- Wednesday, November 23, 1949-Sunday, February 12, 1950 85 Book 80- Monday, February 13, 1950-Saturday, April 22, 1950 92 Book 81- Sunday, April 23, 1950-Friday, June 30, 1950 97 Book 82- Saturday, July 1, 1950-Friday, September 29, 1950 104 Book 83- Saturday, September 30, 1950-Monday, January 8, 1951 113 Book 84- Tuesday, January 9, 1951-Sunday, February 18, 1951 117 Book 85- Sunday, February 18, 1951-Monday, May 7, 1951 125 Book 86- Monday, May 7, 1951-Saturday, June 16, 1951 132 Book 87- Sunday, June 17, 1951-Saturday 11, 1951 144 Book 88- Sunday, November 11, 1951-Saturday, March 22, 1952 150 Book 89- Saturday, March 22, 1952-Wednesday, July 9, 1952 155 ii Book 90- Thursday, July 10, 1952-Sunday, September 7, 1952 164 -

Battersea Reach London SW18 1TA

Battersea Reach London SW18 1TA Rare opportunity to buy or to let commercial UNITS in a thriving SOUTH West London riverside location A prime riverside location situated opposite the River Thames with excellent transport connections. Brand new ground floor units available to let or for sale with Battersea flexible planning uses. Reach London SW18 1TA Units available from 998 sq ft with A1, A3 & E planning uses Local occupiers • Thames-side Battersea location, five minutes from Wandsworth Town station Bathstore • Excellent visibility from York Road which has Mindful Chef c. 75,000 vehicle movements per day Richard Mille • Outstanding river views and and on-site Chelsea Upholstery amenities (including gym, café, gastropub, and Tesco Express) Cycle Republic • Units now available via virtual freehold or to let Fitness Space • Availability from 998 sq ft Randle Siddeley • Available shell & core or Cat A Roche Bobois • Flexible planning uses (A1, A3 & E) • On-site public parking available Tesco Express Yue Float Gourmet Libanais A THRIVING NEW RIVER THAMES NORTH BatterseaA RIVERSIDE DESTINATION ReachB London SW18 1TA PLANNED SCHEME 1,350 RESIDENTIAL UNITS 20a 20b 143 9 3 17 WITH IN EXCESS OF 99% NOW LEGALLY ASCENSIS LOCATION TRAVEL TIMES TOWER COMPLETE OR EXCHANGED Battersea Reach is BALTIMORElocated Richmond COMMODORE14 mins KINGFISHER ENSIGN HOUSE HOUSE HOUSE HOUSE WANDSWORTH BRIDGE near major road links via A3, South Circular (A205) and Waterloo 15 mins 1 First Trade 14 Young’s 23 Wonder Smile A24. KING’S CROSS A10 Bank ST PANCRAS28 mins INTERNATIONAL Waterfront Bar 21a ISLINGTON 2 Cake Boy 24 Ocean Dusk The scheme is five minutesREGENTS EUSTON PARKKing’s Cross 29 mins SHOREDITCH and Restaurant walk from Wandsworth Town15c STATION 8a French Pâtisserie 4 A406 21b 13 10 A1 25 Fonehouse MAIDARailway VALE StationA5 and is a 15b 8b 2 and Coffee Shop 15a Creativemass Heathrow CLERKENWELL31 mins 5 short distance from London15a 8c 18/19 26a PTAH 21c MARYLEBONE A501 4 Gym & Tonic 15b Elliston & NORTH ACTON Heliport. -

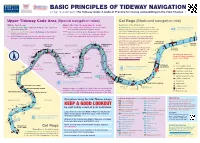

Upper Tideway (PDF)

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF TIDEWAY NAVIGATION A chart to accompany The Tideway Code: A Code of Practice for rowing and paddling on the Tidal Thames > Upper Tideway Code Area (Special navigation rules) Col Regs (Starboard navigation rule) With the tidal stream: Against either tidal stream (working the slacks): Regardless of the tidal stream: PEED S Z H O G N ABOVE WANDSWORTH BRIDGE Outbound or Inbound stay as close to the I Outbound on the EBB – stay in the Fairway on the Starboard Use the Inshore Zone staying as close to the bank E H H High Speed for CoC vessels only E I G N Starboard (right-hand/bow side) bank as is safe and H (right-hand/bow) side as is safe and inside any navigation buoys O All other vessels 12 knot limit HS Z S P D E Inbound on the FLOOD – stay in the Fairway on the Starboard Only cross the river at the designated Crossing Zones out of the Fairway where possible. Go inside/under E piers where water levels allow and it is safe to do so (right-hand/bow) side Or at a Local Crossing if you are returning to a boat In the Fairway, do not stop in a Crossing Zone. Only boats house on the opposite bank to the Inshore Zone All small boats must inform London VTS if they waiting to cross the Fairway should stop near a crossing Chelsea are afloat below Wandsworth Bridge after dark reach CADOGAN (Hammersmith All small boats are advised to inform London PIER Crossings) BATTERSEA DOVE W AY F A I R LTU PIER VTS before navigating below Wandsworth SON ROAD BRIDGE CHELSEA FSC HAMMERSMITH KEW ‘STONE’ AKN Bridge during daylight hours BATTERSEA -

Battersea Area Guide

Battersea Area Guide Living in Battersea and Nine Elms Battersea is in the London Borough of Wandsworth and stands on the south bank of the River Thames, spanning from Fairfield in the west to Queenstown in the east. The area is conveniently located just 3 miles from Charing Cross and easily accessible from most parts of Central London. The skyline is dominated by Battersea Power Station and its four distinctive chimneys, visible from both land and water, making it one of London’s most famous landmarks. Battersea’s most famous attractions have been here for more than a century. The legendary Battersea Dogs and Cats Home still finds new families for abandoned pets, and Battersea Park, which opened in 1858, guarantees a wonderful day out. Today Battersea is a relatively affluent neighbourhood with wine bars and many independent and unique shops - Northcote Road once being voted London’s second favourite shopping street. The SW11 Literary Festival showcases the best of Battersea’s literary talents and the famous New Covent Garden Market keeps many of London’s restaurants supplied with fresh fruit, vegetables and flowers. Nine Elms is Europe’s largest regeneration zone and, according the mayor of London, the ‘most important urban renewal programme’ to date. Three and half times larger than the Canary Wharf finance district, the future of Nine Elms, once a rundown industrial district, is exciting with two new underground stations planned for completion by 2020 linking up with the northern line at Vauxhall and providing excellent transport links to the City, Central London and the West End. -

Parks Open Spaces Timeline

Wandsworth Council Parks time line There are many large green open places in south west London. The commons of Barnes, Battersea, Clapham, Putney, Streatham, Tooting, Wandsworth and Wimbledon date from ‘time immemorial’. Though largely comprising the wastes or heathland of a parish, the commons were integral to mediaeval land settlements and were owned by lords of the manors. As London developed during the nineteenth century the land was increasingly developed for housing. Several legal battles took place to defend the commons as open land. Garratt Green had long been ‘defended’ by the infamous Mayors of Garratt elections. Listed below are the green places in the Borough of Wandsworth that are managed by Wandsworth Parks Service. Further historic information can be found in the individual site management plans. 1858 A Royal Commission into housing recommended creating Battersea Park, Kennington Park, and Victoria Park in Hackney with formal and informal gardens as a way offering moral improvement to an area. Health was a matter of fresh air, exercise and diet, rather than one of medical resources. 1885 Battersea Vestry created Christchurch Gardens as ‘an outdoor drawing room’. The shelter and memorial were added after 1945. 1886 Waterman’s Green was created by the Metropolitan Board of Works as part of the approach to the new Putney Bridge when it was rebuilt in stone. It was not publicly accessible. 1888 Battersea Vestry owned the parish wharf and created Vicarage Gardens as a promenade, complete with ornamental urns on plinths along the river wall. During 1990s it was included in flood defence schemes. 1903 Leader’s Gardens and Coronation Gardens were created as public parks by private donation from two wealthy local individuals. -

MA Dissertatio

Durham E-Theses Northumberland at War BROAD, WILLIAM,ERNEST How to cite: BROAD, WILLIAM,ERNEST (2016) Northumberland at War, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11494/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk ABSTRACT W.E.L. Broad: ‘Northumberland at War’. At the Battle of Towton in 1461 the Lancastrian forces of Henry VI were defeated by the Yorkist forces of Edward IV. However Henry VI, with his wife, son and a few knights, fled north and found sanctuary in Scotland, where, in exchange for the town of Berwick, the Scots granted them finance, housing and troops. Henry was therefore able to maintain a presence in Northumberland and his supporters were able to claim that he was in fact as well as in theory sovereign resident in Northumberland. -

To Volume Xxi

INDEX TO VOLUME XXI A Adelphi Cotton Works, token of the, 190. 7\ = Alexander Tod, moneyer of Adrian IV and Peter's Pence, 17. James III, 70. lEgelmaer the moneyer claimed for A on testoons of Mary probably Stockbridge mint, 160. John Acheson, 72, 148. lElfgifu, daughter of lEthelgifu , 40, 46. A the initial of Anne, Queen of lElfred and the Danes, 9, IO. Henry VIII on his coins, 89, et seq. coins of, 33, 34, 35, 130, A . DOMINO· FACTVM . EST· 159, 18I, 220. ISTVD, legend on Elizabethan cut halfpennies of, 33. counter, 137. death of, II. "A.S.N.Co.", token of Australia, find of coins of, in Rome, 174· 16, 18. 7\T may represent the initials of Gloucester mint of, 56. Thomas Tod and Alexander Levin lEthelbald defeats his Danes, 9. stoun on coins of James III, lEthelflaed, sister of Eadweard the 70-7 I. Elder, II, 12, 18. Abbott, Anthony, badge issued to, lEthelgifu, foster-mother to Eadwig, II4· 40. Aberystwyth mint of Charles I, 143, lEthelheard, Archbishop of Canter 144, 145, 147· bury, coins of, 34. Abor bar to King George V India lEthelred and the Danes, 9. General Service Medal 19II, marries lEthelflaed, 12. 153· of Mercia, death of, 12. " ,medal granted for the punitive lEthelred's London Laws sanction force against, 155. inter alia, workers under the Achesoun, John, engraver, 148. moneyers, 60, 212. moneyer of Mary of lEthelred II, coins of, 53, 159, 160, Scotland, 72, 148. 214-215, 218. Thomas, placks of James HAM PIC coins of, I. VI called " Achesouns " Huntingdon mint of, after, 69 . -

Tenth Annual Conference Multinational Finance Society

MFS Multinational Finance Society http://mfs.rutgers.edu TENTH ANNUAL CONFERENCE MULTINATIONAL FINANCE SOCIETY Sponsored by Ned Goodman Chair in Investment Finance, Concordia University, Canada Institut de finance mathématique de Montréal (IFM2), Canada School of Business-Camden Rutgers University, U.S.A. June 28 - July 2, 2003 Hilton Montréal Bonaventure 900, rue de La Gauchetière Ouest, Suite 10750 Montréal, Québec, Canada H5A 1E4 (800) 267-2575 TENTH ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE MULTINATIONAL FINANCE SOCIETY June 28-July 2, 2003, Montreal, Canada KEYNOTE SPEAKERS Paul Seguin - University of Minnesota Lemma W. Senbet - University of Maryland The conference is organized by the Ned Goodman Chair of Investment Finance, Concordia University, Canada, the Institut de finance mathématique de Montréal (IFM2), Canada, and the School of Business- Camden, Rutgers University. The objective of the conference is to bring together academics and practitioners from all over the world to focus on timely financial issues. Papers presented can be submitted for publication, free of submission fee, in the Multinational Finance Journal, the official publication of the Multinational Finance Society. The Journal publishes refereed papers in all areas of finance, dealing with multinational finance issues. PROGRAM CHAIR Lawrence Kryzanowski - Concordia University, Canada PROGRAM COMMITTEE George Athanassakos - Wilfrid Laurier Univ, Canada Bing Liang - Case Western Reserve University Turan Bali - Baruch College, CUNY Usha Mittoo - University of Manitoba, Canada Geoffrey -

London and Its Main Drainage, 1847-1865: a Study of One Aspect of the Public Health Movement in Victorian England

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 6-1-1971 London and its main drainage, 1847-1865: A study of one aspect of the public health movement in Victorian England Lester J. Palmquist University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Palmquist, Lester J., "London and its main drainage, 1847-1865: A study of one aspect of the public health movement in Victorian England" (1971). Student Work. 395. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/395 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LONDON .ML' ITS MAIN DRAINAGE, 1847-1865: A STUDY OF ONE ASPECT OP TEE PUBLIC HEALTH MOVEMENT IN VICTORIAN ENGLAND A Thesis Presented to the Department of History and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska at Omaha In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Lester J. Palmquist June 1971 UMI Number: EP73033 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI EP73033 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Port of London - River Thames

Port of London - River Thames NOTICE TO MARINERS M54 of 2018 BATTERSEA REACH BATTERSEA RAIL BRIDGE ARCH CLOSURES Contractors working on behalf of Network Rail will be conducting inspection works on Battersea Rail Bridge on Sunday 26th August 2018. In order to accommodate these works, No.2 arch on Battersea Rail Bridge will be closed to navigation as follows: Works Start Works End Navigational Arch Information Date Time Date Time Closed to Navigation and 2 Sunday 26th August 01:00 Sunday 26th August 05:30 Local Traffic Control for Inspection Works Arches closed to navigation will be marked in accordance with the Port of London Authority Thames Byelaws 2012 namely: • By day, three red discs 0.6 metres in diameter at the points of an equilateral triangle with the apex downwards and the base horizontal • By night, three red lights in similar positions to the discs displayed by day Local Traffic Control will be undertaken from a PLA Harbour Service Launch in the vicinity of Battersea Rail Bridge for the duration of the closures in arch 2. All vessels intending to navigate between Albert Bridge and Wandsworth Bridge are to call ‘BATTERSEA CONTROL’ on VHF Channel 14 as follows: • Inbound at Albert Bridge • Outbound at Wandsworth Bridge • Prior to leaving a berth or mooring between Albert Bridge and Wandsworth Bridge All vessels are to navigate in this area with caution, maintaining a continuous watch on VHF Channel 14 and follow the instructions from the attending Harbour Service Launch exhibiting flashing blue lights. Further details will be broadcast by London VTS on VHF Channel Port of London Authority 6th August 2018 London River House, Royal Pier Road, BOB BAKER Gravesend, Kent DA12 2BG CHIEF HARBOUR MASTER EXPIRY DATE: 29th August 2018 TO RECEIVE FUTURE NOTICES TO MARINERS BY E-MAIL, PLEASE REGISTER VIA OUR WEBSITE www.pla.co.uk Telephone calls, VHF radio traffic, CCTV and radar traffic images may be recorded in the VTS Centres at Gravesend and Woolwich .