A Study of the Powers of the Swazi Monarch in Terms of Swazi Law and Custom Past, Present and the Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

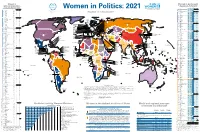

Women in Ministerial Positions, Reflecting Appointments up to 1 January 2021

Women in Women in parliament The countries are ranked and colour-coded according to the percentage of women in unicameral parliaments or the lower house of parliament, ministerial positions reflecting elections/appointments up to 1 January 2021. The countries are ranked according to the percentage of women in ministerial positions, reflecting appointments up to 1 January 2021. Rank Country Lower or single house Upper house or Senate % Women Women/Seats % Women Women/Seats Rank Country % Women Women Total ministers ‡ Women in Politics: 2021 50 to 65% 50 to 59.9% 1 Rwanda 61.3 49 / 80 38.5 10 / 26 1 Nicaragua 58.8 10 17 2 Cuba 53.4 313 / 586 — — / — 2 Austria 57.1 8 14 3 United Arab Emirates 50.0 20 / 40 — — / — ” Belgium 57.1 8 14 40 to 49.9% ” Sweden 57.1 12 21 4 Nicaragua 48.4 44 / 91 — — / — 5 Albania 56.3 9 16 Situation on 1 January 2021 5 New Zealand 48.3 58 / 120 — — / — 6 Rwanda 54.8 17 31 6 Mexico 48.2 241 / 500 49.2 63 / 128 7 Costa Rica 52.0 13 25 7 Sweden 47.0 164 / 349 — — / — 8 Canada 51.4 18 35 8 Grenada 46.7 7 / 15 15.4 2 / 13 9 Andorra 50.0 6 12 9 Andorra 46.4 13 / 28 — — / — ” Finland 50.0 9 18 10 Bolivia (Plurinational State of) 46.2 60 / 130 55.6 20 / 36 ” France 50.0 9 18 11 Finland 46.0 92 / 200 — — / — ” Guinea-Bissau* 50.0 8 16 12 South Africa 45.8 182 / 397 41.5 22 / 53 ” Spain 50.0 11 22 13 Costa Rica 45.6 26 / 57 — — / — 40 to 49.9% 14 Norway 44.4 75 / 169 — — / — 14 South Africa 48.3 14 29 15 Namibia 44.2 46 / 104 14.3 6 / 42 15 Netherlands 47.1 8 17 Greenland Latvia 16 Spain 44.0 154 / 350 40.8 108 / 265 16 -

PRAISES of SOBHUZA II Swaziland Broadcasting Service and Printed to Be Read in Schools

poems, that constituted an official history, recorded for use by the PRAISES OF SOBHUZA II Swaziland Broadcasting service and printed to be read in schools. The following tibongo are by Mabuntane Mdluli, descended from Posted in Praise-Poetry and tagged Sobhuza II, Swaziland. one of the most famous of King Mswati’s warriors. They hint at how Sobhuza II (1899-1982), one of the most remarkable Africans of the inauspiciously Sobuza II’s reign began. last century, was king of Swaziland for 61 years. Educated at the Lovedale Institution in South Africa and an early member of the Dancer on black shields of jojo (1) African National Congress, he was at the same time a passionate You played on shields of shikane traditionalist, pledged as he once put it “to extricate Africa from this Black bewildering widow bird idea of one man one vote”. You grew plumes in winter When other widow birds are bare. The kingdom he inherited was in a disastrous state, and he Where you build recognised from the start the monarchy was his best asset in Stubborn black one of Hhili, (2) combating colonial rule. He played the part with consummate skill, Only he who perseveres survives persuading anthropologists like Max Goodman and Hilda Kuper that He who does not persevere must flee. the Swazis were an ancient nation with ancient customs, and Claw of the lion that is heavy dispatching two regiments, the Emasotja and the Sikonyane, to serve You trod the ocean, (3) with British forces in World war 2, “stabbing and killing” like The ocean surged traditional Swazi warriors, in the Middle East, Tobruk and Anzio. -

Boer War Association Queensland

Boer War Association Queensland Queensland Patron: Major General Professor John Pearn, AO RFD (Retd) Monumentally Speaking - Queensland Edition Committee Newsletter - Volume 12, No. 1 - March 2019 As part of the service, Corinda State High School student, Queensland Chairman’s Report Isabel Dow, was presented with the Onverwacht Essay Medal- lion, by MAJGEN Professor John Pearn AO, RFD. The Welcome to our first Queensland Newsletter of 2019, and the messages between Ermelo High School (Hoërskool Ermelo an fifth of the current committee. Afrikaans Medium School), South Africa and Corinda State High School, were read by Sophie Verprek from Corinda State Although a little late, the com- High School. mittee extend their „Compli- ments of the Season‟ to all. MAJGEN Professor John Pearn AO, RFD, together with Pierre The committee also welcomes van Blommestein (Secretary of BWAQ), laid BWAQ wreaths. all new members and a hearty Mrs Laurie Forsyth, BWAQ‟s first „Honorary Life Member‟, was „thank you‟ to all members who honoured as the first to lay a wreath assisted by LTCOL Miles have stuck by us; your loyalty Farmer OAM (Retd). Patron: MAJGEN John Pearn AO RFD (Retd) is most appreciated. It is this Secretary: Pierre van Blommestein Chairman: Gordon Bold. Last year, 2018, the Sherwood/Indooroopilly RSL Sub-Branch membership that enables „Boer decided it would be beneficial for all concerned for the Com- War Association Queensland‟ (BWAQ) to continue with its memoration Service for the Battle of Onverwacht Hills to be objectives. relocated from its traditional location in St Matthews Cemetery BWAQ are dedicated to evolve from the building of the mem- Sherwood, to the „Croll Memorial Precinct‟, located at 2 Clew- orial, to an association committed to maintaining the memory ley Street, Corinda; adjacent to the Sherwood/Indooroopilly and history of the Boer War; focus being descendants and RSL Sub-Branch. -

A Changing of the Guards Or a Change of Systems?

BTI 2020 A Changing of the Guards or A Change of Systems? Regional Report Sub-Saharan Africa Nic Cheeseman BTI 2020 | A Changing of the Guards or A Change of Systems? Regional Report Sub-Saharan Africa By Nic Cheeseman Overview of transition processes in Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe This regional report was produced in October 2019. It analyzes the results of the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) 2020 in the review period from 1 February 2017 to 31 January 2019. Author Nic Cheeseman Professor of Democracy and International Development University of Birmingham Responsible Robert Schwarz Senior Project Manager Program Shaping Sustainable Economies Bertelsmann Stiftung Phone 05241 81-81402 [email protected] www.bti-project.org | www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/en Please quote as follows: Nic Cheeseman, A Changing of the Guards or A Change of Systems? — BTI Regional Report Sub-Saharan Africa, Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung 2020. https://dx.doi.org/10.11586/2020048 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). Cover: © Freepick.com / https://www.freepik.com/free-vector/close-up-of-magnifying-glass-on- map_2518218.htm A Changing of the Guards or A Change of Systems? — BTI 2020 Report Sub-Saharan Africa | Page 3 Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................... -

Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept of Kingship

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship Jacob Douglas Feeley University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Feeley, Jacob Douglas, "Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2276. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2276 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2276 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship Abstract Scholars who have discussed Josephus’ political philosophy have largely focused on his concepts of aristokratia or theokratia. In general, they have ignored his concept of kingship. Those that have commented on it tend to dismiss Josephus as anti-monarchical and ascribe this to the biblical anti- monarchical tradition. To date, Josephus’ concept of kingship has not been treated as a significant component of his political philosophy. Through a close reading of Josephus’ longest text, the Jewish Antiquities, a historical work that provides extensive accounts of kings and kingship, I show that Josephus had a fully developed theory of monarchical government that drew on biblical and Greco- Roman models of kingship. Josephus held that ideal kingship was the responsible use of the personal power of one individual to advance the interests of the governed and maintain his and his subjects’ loyalty to Yahweh. The king relied primarily on a standard array of classical virtues to preserve social order in the kingdom, protect it from external threats, maintain his subjects’ quality of life, and provide them with a model for proper moral conduct. -

11010329.Pdf

THE RISE, CONSOLIDATION AND DISINTEGRATION OF DLAMINI POWER IN SWAZILAND BETWEEN 1820 AND 1889. A study in the relationship of foreign affairs to internal political development. Philip Lewis Bonner. ProQuest Number: 11010329 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010329 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT The Swazi kingdom grew out of the pressures associated with competition for trade and for the rich resources of Shiselweni. While centred on this area it acquired some of its characteristic features - notably a regimental system, and the dominance of a Dlamini aristocracy. Around 1815 the Swazi came under pressure from the South, and were forced to colonise the land lying north of the Lusutfu. Here they remained for some years a nation under arms, as they plundered local peoples, and were themselves swept about by the currents of the Mfecane. In time a more settled administration emerged, as the aristocracy spread out from the royal centres at Ezulwini, and this process accelerated under Mswati as he subdued recalcitrant chiefdoms, and restructured the regiments. -

Early History of South Africa

THE EARLY HISTORY OF SOUTH AFRICA EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES . .3 SOUTH AFRICA: THE EARLY INHABITANTS . .5 THE KHOISAN . .6 The San (Bushmen) . .6 The Khoikhoi (Hottentots) . .8 BLACK SETTLEMENT . .9 THE NGUNI . .9 The Xhosa . .10 The Zulu . .11 The Ndebele . .12 The Swazi . .13 THE SOTHO . .13 The Western Sotho . .14 The Southern Sotho . .14 The Northern Sotho (Bapedi) . .14 THE VENDA . .15 THE MASHANGANA-TSONGA . .15 THE MFECANE/DIFAQANE (Total war) Dingiswayo . .16 Shaka . .16 Dingane . .18 Mzilikazi . .19 Soshangane . .20 Mmantatise . .21 Sikonyela . .21 Moshweshwe . .22 Consequences of the Mfecane/Difaqane . .23 Page 1 EUROPEAN INTERESTS The Portuguese . .24 The British . .24 The Dutch . .25 The French . .25 THE SLAVES . .22 THE TREKBOERS (MIGRATING FARMERS) . .27 EUROPEAN OCCUPATIONS OF THE CAPE British Occupation (1795 - 1803) . .29 Batavian rule 1803 - 1806 . .29 Second British Occupation: 1806 . .31 British Governors . .32 Slagtersnek Rebellion . .32 The British Settlers 1820 . .32 THE GREAT TREK Causes of the Great Trek . .34 Different Trek groups . .35 Trichardt and Van Rensburg . .35 Andries Hendrik Potgieter . .35 Gerrit Maritz . .36 Piet Retief . .36 Piet Uys . .36 Voortrekkers in Zululand and Natal . .37 Voortrekker settlement in the Transvaal . .38 Voortrekker settlement in the Orange Free State . .39 THE DISCOVERY OF DIAMONDS AND GOLD . .41 Page 2 EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES Humankind had its earliest origins in Africa The introduction of iron changed the African and the story of life in South Africa has continent irrevocably and was a large step proven to be a micro-study of life on the forwards in the development of the people. -

Exploring Zechariah, Volume 2

EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 VOLUME ZECHARIAH, EXPLORING is second volume of Mark J. Boda’s two-volume set on Zechariah showcases a series of studies tracing the impact of earlier Hebrew Bible traditions on various passages and sections of the book of Zechariah, including 1:7–6:15; 1:1–6 and 7:1–8:23; and 9:1–14:21. e collection of these slightly revised previously published essays leads readers along the argument that Boda has been developing over the past decade. EXPLORING MARK J. BODA is Professor of Old Testament at McMaster Divinity College. He is the author of ten books, including e Book of Zechariah ZECHARIAH, (Eerdmans) and Haggai and Zechariah Research: A Bibliographic Survey (Deo), and editor of seventeen volumes. VOLUME 2 The Development and Role of Biblical Traditions in Zechariah Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Boda Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-201-0) available at http://www.sbl-site.org/publications/Books_ANEmonographs.aspx Cover photo: Zev Radovan/BibleLandPictures.com Mark J. Boda Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 ANCIENT NEAR EAST MONOGRAPHS Editors Alan Lenzi Juan Manuel Tebes Editorial Board Reinhard Achenbach C. L. Crouch Esther J. Hamori Chistopher B. Hays René Krüger Graciela Gestoso Singer Bruce Wells Number 17 EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 The Development and Role of Biblical Traditions in Zechariah by Mark J. -

Monthly Forecast

May 2021 Monthly Forecast 1 Overview Overview 2 In Hindsight: Is There a Single Right Formula for In May, China will have the presidency of the Secu- Da’esh/ISIL (UNITAD) is also anticipated. the Arria Format? rity Council. The Council will continue to meet Other Middle East issues include meetings on: 4 Status Update since our virtually, although members may consider holding • Syria, the monthly briefings on political and April Forecast a small number of in-person meetings later in the humanitarian issues and the use of chemical 5 Peacekeeping month depending on COVID-19 conditions. weapons; China has chosen to initiate three signature • Lebanon, on the implementation of resolution 7 Yemen events in May. Early in the month, it will hold 1559 (2004), which called for the disarma- 8 Bosnia and a high-level briefing on Upholding“ multilateral- ment of all militias and the extension of gov- Herzegovina ism and the United Nations-centred internation- ernment control over all Lebanese territory; 9 Syria al system”. Wang Yi, China’s state councillor and • Yemen, the monthly meeting on recent 11 Libya minister for foreign affairs, is expected to chair developments; and 12 Upholding the meeting. Volkan Bozkir, the president of the • The Middle East (including the Palestinian Multilateralism and General Assembly, is expected to brief. Question), also the monthly meeting. the UN-Centred A high-level open debate on “Addressing the During the month, the Council is planning to International System root causes of conflict while promoting post- vote on a draft resolution to renew the South Sudan 13 Iraq pandemic recovery in Africa” is planned. -

Key Principles of Public Sector Reforms

Key Principles of Public Sector Reforms Case Studies and Frameworks Key Principles of Public Sector Reforms Case Studies and Frameworks Advance proof copy. The final edition will be available in December 2016. © Commonwealth Secretariat 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publisher. Views and opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the author and should in no way be attributed to the institutions to which they are affiliated or to the Commonwealth Secretariat. Wherever possible, the Commonwealth Secretariat uses paper sourced from responsible forests or from sources that minimise a destructive impact on the environment. Printed and published by the Commonwealth Secretariat. Table of contents Table of contents ........................................................................................ 1 Acknowledgements ...................................................................................... 3 Foreword .................................................................................................. 5 The Key Principles of Public Sector Reform ......................................................... 8 Principle 1. A new pragmatic and results–oriented framework ................................. 12 Case Study 1.1 South Africa. Measuring organisational productivity in the public service: North -

The Structural Origins of Authoritarianism in Pakistan

CDDRL Number 116 WORKING PAPERS October 2009 The Origins of Authoritarianism in Pakistan Sumit Ganguly Indiana University, Bloomington Center on Democracy, Development, and The Rule of Law Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies Additional working papers appear on CDDRL’s website: http://cddrl.stanford.edu. Center on Democracy, Development, and The Rule of Law Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies Stanford University Encina Hall Stanford, CA 94305 Phone: 650-724-7197 Fax: 650-724-2996 http://cddrl.stanford.edu/ About the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law (CDDRL) CDDRL was founded by a generous grant from the Bill and Flora Hewlett Foundation in October in 2002 as part of the Stanford Institute for International Studies at Stanford University. The Center supports analytic studies, policy relevant research, training and outreach activities to assist developing countries in the design and implementation of policies to foster growth, democracy, and the rule of law. TTThhheee OOOrrriiigggiiinnnsss ooofff AAAuuuttthhhooorrriiitttaaarrriiiaaannniiisssmmm iiinn PPPaaakkkiiissstttaaannn Sumit Ganguly Introduction What ails the Pakistani polity? Since its emergence from the detritus of the British Indian Empire in 1947, it has witnessed four military coups (1958, 1969, 1978 and 1999), long periods of political instability and a persistent inability to consolidate democratic institutions. It also witnessed the loss of a significant portion of its territory (East Pakistan) in 1971 following the brutal suppression of an indigenous uprising in the aftermath of which some ten million individuals sough refuge in India. The flight of the refugees to India and the failure to reach a political resolution to the crisis precipitated Indian military intervention and culminated in the creation of the new state of Bangladesh.i Pakistan’s inability to sustain a transition to democracy is especially puzzling given that India too emerged from the collapse of British rule in South Asia. -

The Impact of Impucuko (Modernisation) of Rural Homestead Living Spaces on the Dwellers in a Selected Area of Umbumbulu, South of Durban

THE IMPACT OF IMPUCUKO (MODERNISATION) OF RURAL HOMESTEAD LIVING SPACES ON THE DWELLERS IN A SELECTED AREA OF UMBUMBULU, SOUTH OF DURBAN. Submitted in fulfilment of the degree MASTER OF APPLIED ARTS IN INTERIOR DESIGN FACULTY OF ARTS AND DESIGN Candidate: HLENGIWE MLAMBO Student Number 20513142 Institution DURBAN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF VISUAL COMMUNICATION DESIGN Supervisor PROF BRIAN PEARCE Co-supervisor PROF RODNEY HARBER DATE: 28 APRIL 2016 1 2 ABSTRACT This study discusses the impact of modernisation of rural homestead living spaces on dwellers in a selected area of Umbumbulu, south of Durban Kwa-Zulu Natal South Africa. The study was conducted after a change was noticed within the rural homesteads built environment. Factors responsible for the changes in building/ dwelling shape, size, style, as well as the choice of materials (SSSM) used were discussed. The study further examined the impact of the listed changes within the social context of Umbumbulu’s rural dwellers, while addressing in-depth questions around the topic of modernisation, especially within the confines of rural homesteads and living spaces. A qualitative research approach was employed where an interpretative research paradigm was chosen as a theoretical framework for the study. Data consisted of seven semi structured interviews. The research design consisted of themes, the analysis, as well as the findings in relation to literature. The conclusion showed what the rural dwellers understand about modernisation in a rural context, as well as how it has impacted the changes in building/ dwelling shape, size, style, as well as in the choice of materials used. Three identifiable themes were discussed namely: 1.