(1) the End Times Our Hope & God's Promise Part One Individual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studies in Romans

Abilene Christian University Digital Commons @ ACU Stone-Campbell Books Stone-Campbell Resources 1957 Studies in Romans R. C. Bell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/crs_books Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Bell, R. C., "Studies in Romans" (1957). Stone-Campbell Books. 470. https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/crs_books/470 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Stone-Campbell Resources at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Stone-Campbell Books by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ACU. STUDIESIN ROMANS R.C.BELL F IRM FOUNDATION PUBLISHING HOUSE AUSTIN , TEXAS COPYRIGHT, 1887 FIRM FOUNDATION PUBLISHING HOU SE LESSON 1 Though Romans was written near the close of Paul's mis sionary ministry, reasonably, because of its being a fuller 1-1.ndmore systematic discussion of the fundamentals of Christianity than the other Epistles of the New Testament, 'it is placed before them. Paul's earliest writings, the Thes salonian letters, written some five years before Romans, rea sonably, because they feature Christ's second coming and the end of the age, are placed, save the Pastoral Epistles and Philemon, last of his fourteen Epistles. If Mordecai, with out explicit evidence, believed it was like God to have Esther on the throne at a most crucial time (Esther 4 :14), why should it be "judged incredible" that God had some ~hing to do with this arrangement of his Bible? The theme of the Bible from Eden onward is the redemp tion of fallen man. -

Today We Have This Powerful Story of the Raising of the Widow's Son from the Dead. We Know There Are a Couple of Other Exampl

Today we have this powerful story of the raising of the widow’s son from the dead. We know there are a couple of other examples in the Scriptures of Jesus raising people from the dead. Of course, the story of the raising of Lazarus and the story of the raising of the daughter of Jairus. But this raising story, you’ll notice, is a little different. In this story no one is asking Jesus for help. For Lazarus, Martha says “If you had been here, my brother would not have died.” Jairus says, “My daughter is at the point of death. Please, come lay your hands on her that she may get well and live.” Jesus sets on His own initiative and in this we see His great compassion. Let’s look at the scene a little closer. The one who died was the only son of a widow. So she was alone. Her husband had died, and now her only son had died, so she has the terrible grief of losing her son after already having lost her husband. She has the prospect now of being alone, and on top of this, in those days women didn’t really work for income. So now she has to be completely dependent on the charity of others to live. Maybe she now would even have to be reduced to begging. The Lord sees all this going on. The exact scripture we heard was: “When the Lord saw her, He was moved with pity for her.” So we see the Lord’s great compassion here. -

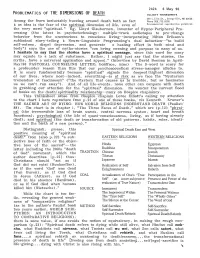

A Practitioner's Guide to Culturally Sensitive Practice for Death and Dying Texas Long Term Care Institute

A Practitioner's Guide to Culturally Sensitive Practice for Death and Dying Prepared By Merri Cohoe, BSW Sue Ellen Contreras, BSW Debra Sparks, BSW Texas Long Term Care Institute College of Health Professions Southwest Texas State University San Marcos, Texas TLTCI Series Report 02-2 April 2002 Information presented in this document may be copied for non-commercial purposes only. Please credit the Texas Long Term Care Institute. Additional copies may be obtained from the Texas Long Term Care Institute, 601 University Drive, San Marcos, Texas, 78666 Phone: 512-245-8234 FAX 512-245-7803. Email: L [email protected] Website: http://LTC-Institute.health.swt.edu CWe; w.auU eJw [o;~ tJus; ~fl/ [o;OU/tI~iIv~4tAwv~, ~, and~tuJi4i1vOW1l~. CWe; w.auU ~ eJw [0; ~ aft tJuv Soci.at CW~ wJuy Iuwe; ~ t/te; uuuJ; I<w USJ. ~it is; 0W1I ~ widv [0; ~ tAerrv p;uuul. 2 Table of Contents Introduction ....... ........................................................................ 5 Acknowledgements .......................... ...... ..... ... ............. .............. .... 6 African Methodist Episcopal .................. , ................. " ........... , .... ... .. .. 7 American Evangelical. .. 8 Anglican .................................................................................... 9 Anglican Catholic Church ......... " . " ................................................ '" 10 Assemblies of God .............. , ..... .................... ................ ....... .......... 11-12 Atheism..... .................. ....... .................... ............... -

The Human Encounter with Death

The Human Encounter With Death by STANISLAV GROF, M.D. & JOAN HALIFAX, PH.D. with a Foreword by ELISABETH KÜBLER-ROSS, M.D D 492 / A Dutton Paperback / $3.95 / In Canada $4.75 Stanislav Grof, M.D., and Joan Halifax, Ph.D., have a unique authority and competence in the interpretation of the human encounter with death. Theirs is an extraordin ary range of experience, in clinical research with psyche- delic substances, in cross-cultural and medical anthropology, and in the analysis of Oriental and archaic literatures. Their pioneering work with psychedelics ad ministered to individuals dying of cancer opened domains of experience that proved to be nearly identical to those al ready mapped in the "Books of the Dead," those mystical visionary accounts of the posthumous journeys of the soul. The Grof/Halifax book and these ancient resources both show the imminent experience of death as a continuation of what had been the hidden aspect of the experience of life. —Joseph Campbell The authors have assisted persons dying of cancer in tran scending the anxiety and anger around their personal fate. Using psychedelics, they have guided the patients to death- rebirth experiences that resemble transformation rites practiced in a variety of cultures. Physician and medical anthropologist join here in recreating an old art—the art of dying. —June Singer The Human Encounter With Death is the latest of many re cent publications in the newly evolving field of thanatology. It is, however, a quite different kind of book—one that be longs in every library of anyone who seriously tries to un derstand the phenomenon we call death. -

Problematics of the Dimensions of Death

2424 6 May 90 PROBLEMATICS OF THE DIMENSIONS OF DEATH ELLIOTT THINKSHEETS 309 L.Eliz.Dr., Craigville, MA 02636 Among the fears ineluctably buzzing around death both as fact Phone 508.775.8008 & as idea is the fear of the spiritual dimension of life, even of Noncommercial reproduction permitted the very word "spiritual." Eg, Lloyd Glaubermen, inventor of Hypno-Peripheral Pro- cessing (the latest in psychotechnology: multiple-track audiotapes to pre-change behavior from the unconscious to conscious living--incorporating Milton Erikson's subliminal story-telling & Neuro-Linguistic Programming's dual induction--"to build self-esteem, dispel depression, and generate a healing effect in both mind and body") says the use of myths-stories "can bring meaning and purpose to many of us. I hesitate to say that the stories have a spiritual message , since this word for many may equate to a lack of substance. Rather, I might just say that the stories, the myths, have a universal application and appeal." (Interview by David Beeman in April- May/90 PASTORAL COUNSELING LETTER; boldface, mine) The S-word is scary for a profounder reason than this that our psychoacoustical stress-manager alludes to. It is scary fundamentally because "spiritual" signals the deepest/highest dimension of our lives, where most--indeed, everything--is at risk as we face the "Mysterium tremendum et fascinosum" ("the Mystery that causes us to tremble, but so fascinates us we can't run away"). And of all life-events, none other can compare with death in grabbing our attention for the "spiritual" dimension. No wonder the current flood of books on the death/spirituality relationship--many on Hospice chaplaincy. -

Death in the Spirituality of the Desert Daniel Lemeni

The Untimely Tomb: Death in the Spirituality of the Desert Daniel Lemeni UDC: 27-788"03/05" D. Lemeni 27-35"03/05" West University of Timişoara Review Faculty of Teology Manuscript received: 22. 10. 2016. Str. Intrarea Sabinei, nr.1, ap. 6 Revised manuscript accepted: 07. 02. 2017. 300422 Timişoara, Timiş, Romania DOI: 10.1484/J.HAM.5.113743 [email protected] In this paper we will explore the “practice of death” in the spirituality of the desert. e paper is divided into two sections. Section 1 explores the desert as place of the death. e monk has symbolized this death by locating his existence in the desert, because the renunciation of secular life led the monk to regard himself as dead. Section 2 points out depictions of monks as dead or entombed. We will examine here the role played by “daily dying” in the Life of Antony. Antony the Great characterizes his life as a kind of “death”, because he lives as though dying each day. In other words, the monk, though not actually dead, eectively dies each day. is kind of “death” (daily dying) contains the seeds of later ascetic tradition on a “practice of death”. Keywords: death, Desert Fathers, Late Antiquity, monasticism, Antony the Great. INTRODUCTION growth of monasticism in fourth-century Egypt has long been recognized as one of the most significant and alluring The withdrawal from the world is the most powerful moments of early Christianity. In the withdrawal from the metaphor to describe the mortification in the spirituality mainstream of society and culture to the stark solitude of of the desert. -

©2011 Steven M. Kawczak All Rights Reserved

©2011 STEVEN M. KAWCZAK ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BELIEFS AND APPROACHES TO DEATH AND DYING IN LATE SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLAND A Dissertation Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Steven M. Kawczak December, 2011 BELIEFS AND APPROACHES TO DEATH AND DYING IN LATE SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLAND Steven M. Kawczak Dissertation Approved: Accepted: ____________________________ ____________________________ Advisor Department Chair Michael F. Graham, Ph.D. Michael Sheng, Ph.D. ____________________________ ____________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the College Michael Levin, Ph.D. Chand K. Midha, Ph.D. ____________________________ ____________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Constance Bouchard, Ph.D. George R. Newkome, Ph.D. ____________________________ ____________________________ Faculty Reader Date Howard Ducharme, Ph.D. ____________________________ Faculty Reader Matthew Crawford, Ph.D. ii ABSTRACT This dissertation is about death and its relationship to religion in late seventeenth- century England. The primary argument is that while beliefs about death stemmed from the Reformation tradition, divergent religious reforms of Puritanism and Arminianism did not lead to differing approaches to death. People adapted religious ideas on general terms of Protestant Christianity and not specifically aligned with varying reform movements. This study links apologetics and sermons concerning spiritual death, physical death, and remedies for each to cultural practice through the lens of wills and graves to gauge religious influence. Readers are reminded of the origins of reformed thought, which is what seventeenth-century English theologians built their ideas upon. Religious debates of the day centered on the Puritan and Arminian divide, which contained significantly different ideas of soteriology, a key aspect of a good death in the English ars moriendi. -

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title The making of a shaman: Calling, training and culmination Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4n0767rw Journal Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 34(3) Author Walsh, RN Publication Date 1994 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California THE MAKING OF A SHAMAN: CALLING, TRAINING, AND CULMINATION ROGER WALSH is a professor of psychiatry, phi losophy, and anthropology at the University of California at Irvine. His publications include The Spirit of Shamanism, Meditation: Classic and Contemporary Perspectives, and Paths Beyond Ego: The Transpersonal Vision. Summary Shamanism and especially the psychological health of shamans remain topics of considerable confusion. This article, therefore, examines the shamanic training process from a specifically psycho logical perspective. Much in this ancient tradition that formerly appeared arcane, nonsensical, or pathological is found to be under standable in psychological terms. The initial shamanic crisis is seen to be a culture-specific form of developmental crisis rather than being evidence of severe psychopathology. Commonalities are noted between certain shamanic training experiences and those of other religious traditions and various psychotherapies. Psychologically effective shamanic techniques are distinguished from merely super stitious practices and several shamanic techniques are seen to foreshadow ones now found in contemporary -

GENESIS 1 – 3 and the CROSS the Connection Between the Gospel and the Creation Scriptures?

GENESIS 1 – 3 AND THE CROSS The connection between the Gospel and the creation Scriptures? The story of the Bible begins with God in eternal glory before the beginning of time and history, and it ends with God and his redeemed people in eternal glory. At the center stands the cross, where God revealed his glory through his Son. The history of salvation is the grand overarching story of the Bible; embracing it gives coherence to all of life. It calls each of God's people to own the story personally and it dignifies each believer with a role in the further outworking of the story. The biblical story of redemption must be understood within the larger story of creation. First Adam, and later Israel, were placed in God's sanctuary… the Garden of Eden and the Promised Land, respectively. But both Adam and Israel failed to be a faithful, obedient steward, and both were expelled from the sanctuary God had created for them. But Jesus Christ—the second Adam, the son of Abraham, the son of David—was faithful and obedient to God. Though the world killed him, God raised him to life, which meant that death was defeated. Through his Spirit, God pours into sinners the resurrection life of his Son, creating a new humanity “in Christ.” Those who are “in Christ” move through death into new life and exaltation in God's sanctuary, there to enjoy his presence forever. Genesis and origins The English title “Genesis” comes from the Greek translation of the Pentateuch and means “origin,” a very apt title because Genesis is all about origins—of the world, of the human race, of sin, death, and of the Jewish people. -

The Christian View of Life and Death

The Christian View of Life and Death In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He [the Son] was with God [the Father] in the beginning. Through him all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made. In him was life, and that life was the light of men. The light shines in the darkness, but the darkness has not understood it. (John 1:1-5) In the history of our universe, life came first…then death, suffering, and ruin as a consequence of an ancient tragedy. In the original languages, the sixty-six books of God’s Word (Bible) repeatedly speak of two kinds of life—physical and spiritual, as well as two kinds of death—physical and spiritual. At the creation, the first man—Adam, like the rest of the universe, was formed from molecular elements. “The Lord God formed the man from the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life [spiritual] and man became a living being.” (Genesis 2:7) Adam had unique and transcendent attributes of intellect, emotions, and will--personhood. This personhood is a reflection [image] of God’s similar attributes. Initially, Adam had an intimate and loving relationship with his Creator. The first mention of death comes only ten verses later. And the Lord God commanded the man, “You are free to eat from any tree in the garden; but you must not eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, for when you eat of it you will surely die.” (Genesis 2:16, 17) Death means separation, not extinction or cessation. -

Death and Life and the Bible Robin C

Death and Life and the Bible Robin C. Calamaio freelygive-n.com Copyright 2006 – Edit 2019 Death first. Is death just a part of life? Is it simply an impersonal, random event with no hostile intent? All longevity models (evolution) think so. On the other hand, if death is imposed - that changes everything. What a massive understatement. Evolution and Biblical Creationism, are the two primary competitors in Western thought on origins. They are at great odds on this subject. Indeed, the two systems could not be more diametrically opposed. Here is a comparative review of these two belief systems. Compare point 1 to point 1, point 2 to point 2, etc. Evolution: 1. Death has been present from the beginning of life. 2. Death is natural and absolutely imperative to evolutionary progression. 3. All life has been dominated by death from the start. 4. Death did not “spread” to humans. As stated earlier, it has been present from life’s start. 5. Death may be an enemy from an individual’s point of view, but from an evolutionary view, it is a natural, and necessary, part of the progression of the species. 6. There is but one death for any living thing. Death forever extinguishes the individual life. 7. This existence is all that is. All will continue in random development just as all has randomly evolved. As long as there is life, death will be a universal constant. Biblical Creationism: 1. Death was totally absent from our completed, original heavens and earth. 2. Death is unnatural and was imposed as a judgement by God in response to Adam’s sin. -

The Bible and Death?” Genesis 2:15–17 Dr

I. Eternity in Biblical Perspective If I Should Die Before I Wake... “The Bible and Death?” Genesis 2:15–17 Dr. Harry L. Reeder III January 19, 2020 • Evening Sermon This is not an expositional consecutive text but an expositional topical text. The reason I have chosen this series eternity in Biblical perspective was not because of the recent passing of my sister, although it has coincided with this challenging providence, but some of the reasons go way back to God’s call on my life. At the time I was called to the ministry the attractive thing to do was to go into parachurch ministry, like Campus Crusade, InterVarsity and Navigators, and all of which I highly value. So the men who were pretty gifted would do that and the other ones would be told to go get a church somewhere so that was kind of the way it was viewed. In my college years and early years in seminary my heart went the other direction, because when I would study the Scripture it would tell me that Jesus went to the cross to purchase His church with His own blood and that Jesus had given Himself for the church, His bride, to secure her. He had gifted pastors and teachers for the equipping of the saints in the church so that they could do the work of the ministry. God’s plan of His Great Commission and equipping people with the Great Commandment was worked out in the context of the church. It was abundantly clear in the book of Acts that when God turned the world upside down He did it through leaders rooted in churches, like Ephesus, Jerusalem, Rome and Antioch.