US Catholic Charismatics and Their Ecumenical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sacraments of Initiation in the Work of Pius Parsch with an Outlook Towards the Second Vatican Council’S Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy

THE SACRAMENTS OF INITIATION IN THE WORK OF PIUS PARSCH WITH AN OUTLOOK TOWARDS THE SECOND VATICAN COUNCIL’S CONSTITUTION ON THE SACRED LITURGY A Dissertation Submitted to the Catholic Theological Faculty of Paris Lodron University, Salzburg in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Theology by Saji George Under the Guidance of Uni.-Prof. Dr. Rudolf Pacik Department of Practical Theology Salzburg, November 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe a debt of gratitude to those who have helped me in the course of writing this dissertation. First of all, with the Blessed Virgin Mary, I thank the Triune God for all His graces and blessings: “My soul magnifies the Lord and my spirit rejoices in God my Saviour, […] for the Mighty One has done great things for me and holy is his name” (Lk. 1: 46-50). I express my heartfelt gratitude to Prof. Dr. Rudolf Pacik, guide and supervisor of this research, for his worthwhile directions, valuable suggestions, necessary corrections, tremendous patience, availability and encouragement. If at all this effort of mine come to an accomplishment, it is due to his help and guidance. I also thank Prof. Dr. Hans-Joachim Sander for his advice and suggestions. My thanks are indebted to Mag. Gertraude Vymetal for the tedious job of proof-reading, patience, suggestions and corrections. I remember with gratitude Fr. Abraham Mullenkuzhy MSFS, the former Provincial of the Missionaries of St. Francis De Sales, North East India Province, who sent me to Salzburg for pursuing my studies. I appreciate his trust and confidence in me. My thanks are due to Fr. -

![The Charismatic Movement and Lutheran Theology [1972]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7475/the-charismatic-movement-and-lutheran-theology-1972-67475.webp)

The Charismatic Movement and Lutheran Theology [1972]

THE CHARISMATIC MOVEMENT AND LUTHERAN THEOLOGY Pre/ace One of the significant developments in American church life during the past decade has been the rapid spread of the neo-Pentecostal or charis matic movement within the mainline churches. In the early sixties, experi ences and practices usually associated only with Pentecostal denominations began co appear with increasing frequency also in such churches as the Roman Catholic, Episcopalian, and Lutheran. By the mid-nineteen-sixties, it was apparent that this movement had also spread co some pascors and congregations of The Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod. In cerrain areas of the Synod, tensions and even divisions had arisen over such neo-Pente costal practices as speaking in tongues, miraculous healings, prophecy, and the claimed possession of a special "baptism in the Holy Spirit." At the request of the president of the Synod, the Commission on Theology and Church Relations in 1968 began a study of the charismatic movement with special reference co the baptism in the Holy Spirit. The 1969 synodical convention specifically directed the commission co "make a comprehensive study of the charismatic movement with special emphasis on its exegetical aspects and theological implications." Ie was further suggested that "the Commission on Theology and Church Relations be encouraged co involve in its study brethren who claim to have received the baptism of the Spirit and related gifts." (Resolution 2-23, 1969 Pro ceedings. p. 90) Since that time, the commission has sought in every practical way co acquaint itself with the theology of the charismatic movement. The com mission has proceeded on the supposition that Lutherans involved in the charismatic movement do not share all the views of neo-Pentecostalism in general. -

Inner Healing and Deliverance As an Essential Component of The

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Doctor of Ministry Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2017 Inner Healing and Deliverance as an Essential Component of the Discipleship Structure of the Local Church Jonathan Lee Shoo Chiang George Fox University, [email protected] This research is a product of the Doctor of Ministry (DMin) program at George Fox University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Shoo Chiang, Jonathan Lee, "Inner Healing and Deliverance as an Essential Component of the Discipleship Structure of the Local Church" (2017). Doctor of Ministry. 234. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dmin/234 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Ministry by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GEORGE FOX UNIVERSITY INNER HEALING AND DELIVERANCE AS AN ESSENTIAL COMPONENT OF THE DISCIPLESHIP STRUCTURE OF THE LOCAL CHURCH A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF PORTLAND SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY JOHNATHAN LEE SHOO CHIANG PORTLAND, OREGON OCTOBER 2017 CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL DMIN DISSERTATION This is to certify that the DMIN Dissertation of Johnathan Lee Shoo Chiang Has been approved by The Dissertation Committee on October 6, 2017 For the degree of Doctor of Ministry in Leadership and Spiritual Formation Dissertation Committee: Primary Advisor: Dr. Leah Payne Secondary Advisor: Dr. Mark Chironna Expert Advisor: Dr. Aida Ramos Copyright 2017© Johnathan Lee Shoo Chiang All rights reserved ii CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ....................................................................................... -

St. John the Evangelist Upper Room Pentecost Novena

St. John the Evangelist Upper Room Pentecost Novena Nights 1 – 8 Night 9 Friday, May 22 to Saturday, May 30 Friday, May 29 Extended Pentecost Vigil 8:00 – 9:00 pm Mass 7:00 pm Our Plan Each night of our Novena we’ll place ourselves in the Upper Room with Mary and Apostles. We’ll spend time in prayer and worship and then listen to a short, encouraging real-life testimony from a parishioner about one of nine ways the Holy Spirit works in our life. After that we’ll have quiet time before Jesus in the Eucharist, to ask him and the Father to pour out the Holy Spirit upon us. We’ll end the evening praying the Chaplet of the Holy Spirit together as we intercede for the Church and the world, and for the fulfillment of Jesus’ promise that we would be baptized in the Holy Spirit. What Does The Holy Spirit Want To Do In Us? The Holy Spirit creates a desire and longing for prayer. The Holy Spirit brings us real joy in a world of passing pleasures. The Holy Spirit creates a hunger for reading Scripture. The Holy Spirit stirs up a genuine sorrow for sin and desire for new life in Christ. The Holy Spirit gives us boldness and courage to live out the faith in daily life. The Holy Spirit gives us supernatural peace. The Holy Spirit brings us into a personal relationship with Jesus. The Holy Spirit gives us a sense of mission and purpose in everyday life. The Holy Spirit teaches us the truth (about God, ourselves, the world, etc.). -

SFFA V. Harvard: How Affirmative Action Myths Mask White Bonus

Boston University School of Law Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law Faculty Scholarship 4-2019 SFFA v. Harvard: How Affirmative Action Myths Mask White Bonus Jonathan P. Feingold Boston University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Jonathan P. Feingold, SFFA v. Harvard: How Affirmative Action Myths Mask White Bonus, 107 California Law Review 707 (2019). Available at: https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship/828 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SFFA v. Harvard: How Affirmative Action Myths Mask White Bonus Jonathan P. Feingold* In the ongoing litigation of Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard College, Harvard faces allegations that its once-heralded admissions process discriminates against Asian Americans. Public discourse has revealed a dominant narrative: affirmative action is viewed as the presumptive cause of Harvard’s alleged “Asian penalty.” Yet this narrative misrepresents the plaintiff’s own theory of discrimination. Rather than implicating affirmative action, the underlying allegations portray the phenomenon of “negative action”—that is, an admissions regime in which White applicants take the seats of their more qualified Asian-American counterparts. Nonetheless, we are witnessing a broad failure to see this case for what it is. This misperception invites an unnecessary and misplaced referendum on race-conscious admissions at Harvard and beyond. -

JACKSON-THESIS-2016.Pdf (1.747Mb)

Copyright by Kody Sherman Jackson 2016 The Thesis Committee for Kody Sherman Jackson Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Jesus, Jung, and the Charismatics: The Pecos Benedictines and Visions of Religious Renewal APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Robert Abzug Virginia Garrard-Burnett Jesus, Jung, and the Charismatics: The Pecos Benedictines and Visions of Religious Renewal by Kody Sherman Jackson, B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2016 Dedication To all those who helped in the publication of this work (especially Bob Abzug and Ginny Burnett), but most especially my brother. Just like my undergraduate thesis, it will be more interesting than anything you ever write. Abstract Jesus, Jung, and the Charismatics: The Pecos Benedictines and Visions of Religious Renewal Kody Sherman Jackson, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2016 Supervisor: Robert Abzug The Catholic Charismatic Renewal, though changing the face and feel of U.S. Catholicism, has received relatively little scholarly attention. Beginning in 1967 and peaking in the mid-1970s, the Renewal brought Pentecostal practices (speaking in tongues, faith healings, prophecy, etc.) into mainstream Catholicism. This thesis seeks to explore the Renewal on the national, regional, and individual level, with particular attention to lay and religious “covenant communities.” These groups of Catholics (and sometimes Protestants) devoted themselves to spreading Pentecostal practices amongst their brethren, sponsoring retreats, authoring pamphlets, and organizing conferences. -

We, the Family of St. Angela Merici Catholic Church, Welcome All to Our Parish of Spirit- Filled Worship

We, the family of St. Angela Merici Catholic Church, welcome all to our parish of spirit- filled worship. We celebrate our love for Jesus and our diversity through faith formation, evangelization, and service. Rev. David Klunk Administrator Rev. Francis Ng Parochial Vicar Deacon Benjamin Flores Deacon Mike Shaffer Our Parish Deacons Rev. Dan Mc Sweeney S.S.C.C Sunday Ministry Rev. Bruce Patterson In Residence Celebration of the Eucharist Monday-Friday 8:00 am & 6:00 pm Saturday 8:00 am & 5:00 pm Vigil, Sunday 7:45 am, 9:30 am, 11:15 am 12:45 Spanish, 5:00 pm Adoration Chapel Monday-Saturday 9:00 am - 12:00 midnight Sacrament of Reconciliation Saturday 3:30 - 4:30 pm Or by Appointment Office Hours Monday - Friday 8:00 am - 2:00 pm Monday - Thursday 4:00 pm - 8:00 pm Saturday & Sunday 8:30 am - 12:00 Noon Happy Easter! Jesus is Risen, Alleluia, Alleluia!! May 10, 2020 We all miss you very much and hope you're staying healthy and staying in prayer. Life is still very busy around here; I want to take this opportunity to update and share some of God's Good News with you. Mother's Day Drive-Thru Blessing Looking for something special to do TODAY? Please come to our Mother's Day Drive-Thru to re- ceive a special blessing and gift from 10am to noon in the church parking lot. All the clergy will be there and hope you will as well. Also, please mark your calendars for Adoration of the Blessed Sacra- ment and Benediction on May 23 at 6:30 pm in the Church parking lot as well as a drive thru bless- ing on May 31 from 10 am to noon for the Feast of Pentecost. -

2019 Summer Issue

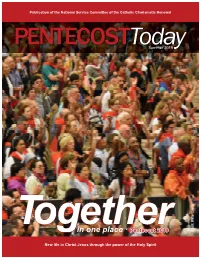

Publication of the National Service Committee of the Catholic Charismatic Renewal PENTECOSTToday Summer 2019 in one place · Pentecost 2019 fromPhoto CHARIS New life in Christ Jesus through the power of the Holy Spirit Chairman’s Editor’s Corner Desk . by Ron Riggins by Sr. Mary Anne Schaenzer, SSND in the unity of those who believe in Christ (Eph 4:11-16). hen I read the word “sandals” in In Pursuit of Unity Ron Riggins’ article concerning the CHARIS captures the unity preached Winauguration of CHARIS, and sandals esus prayed for our unity: “that they by Jesus and later by St. Paul, as Pope spiritually symbolizing readiness to serve, I may all be one” (Jn 17:20-21). And Francis sees baptism in the Holy Spirit recalled a quote regarding sandals: “Put Jin the Nicene Creed we profess as an opportunity for the whole Church. them on and wear them like they fi t.” Or as our belief that the Church is one. He expects those of us who have ex- Ron calls the NSC, Boots on the Ground. The motto in Alexandre Dumas’ novel perienced this current of grace to work CHARIS (Catholic Charismatic Renewal The Three Musketeers reflected a commit- together, using our diverse gifts, for International Service) inaugurated by Pope ment to unity: un pour tous, tous pour un unity in the Renewal and ecumenically Francis, is “marked by communion between (“one for all, all for one”). But then in the Body of Christ for the benefit of all the members of the charismatic family, in Frank Sinatra sang what seems to be the whole Church. -

PRAISE HIM! May/June 2017

Disciples of the Lord Jesus Christ Publication Volume XLIV No. 3 PRAISE HIM! May/June 2017 Hungering and Thirsting for God by Dr. Tom Curran Blessed Elena Guerra “Missionary of the Holy Spirit” by Christof Hemberger The Duquesne Weekend by Patti Gallagher Mansfield A Note From Mother Juana Teresa Chung, DLJC Superior General Dear Friends, Jesus loves you! It is a great joy to continue to celebrate the Jubilee of Catholic Charismatic Renewal! One of the things that I have been meditating upon is, the double portion of the Spirit that Elisha asked Elijah in 2 Kings 2:9. As I read these words, I was inspired to ask the Lord for more of the Holy Spirit, for an increase of the Sanctifying gifts and charisms for the service of the Church. Let me share with you some of the things that I have been doing to be better disposed to receive more of His Holy Spirit. First, for the increase of the Sanctifying gifts, I have been meditating upon and have been more aware of God’s grace in my life in day-to-day situations. In addition, I have decided to increase my visits to the Blessed Sacrament because He is the source of these gifts. God has given us these beautiful gifts so that we may be more like Him. What a joy and consolation is to know that we can rely on His mighty and powerful gifts to grow in His likeness. Secondly, for the increase of the charism for the service of the Church, I have been studying, asking questions about the gifts from those people who manifest the charisms, and then praying for these gifts. -

COLLECTION 0076: Papers of Alex V. Bills, 1906-1999

Fuller Theological Seminary Digital Commons @ Fuller List of Archival Collections Archives and Special Collections 2018 COLLECTION 0076: Papers of Alex V. BIlls, 1906-1999 Fuller Seminary Archives and Special Collections Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fuller.edu/findingaids Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the Missions and World Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Fuller Seminary Archives and Special Collections, "COLLECTION 0076: Papers of Alex V. BIlls, 1906-1999" (2018). List of Archival Collections. 29. https://digitalcommons.fuller.edu/findingaids/29 This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at Digital Commons @ Fuller. It has been accepted for inclusion in List of Archival Collections by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Fuller. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Archives, Rare Books and Special Collections David Allan Hubbard Library Fuller Theological Seminary COLLECTION 76: Papers of Alex V. Bills, 1906-1999 Table of Contents Administrative Information ..........................................................................................................2 Biography ........................................................................................................................................3 Scope and Content ..........................................................................................................................4 Arrangement ...................................................................................................................................5 -

Affirming Affirmative Action by Affirming White Privilege: SFFA V

Affirming Affirmative Action by Affirming White Privilege: SFFA v. Harvard JEENA SHAH* INTRODUCTION Harvard College’s race-based affirmative action measures for student admissions survived trial in a federal district court.1 Harvard’s victory has since been characterized as “[t]hrilling,” yet “[p]yrrhic.”2 Although the court’s reasoning should be lauded for its thorough assessment of Harvard’s race-based affirmative action, the roads not taken by the court should be assessed just as thoroughly. For instance, NYU School of Law Professor Melissa Murray commented that, much like the Supreme Court’s seminal decision in Grutter v. Bollinger3 (which involved the University of Michigan Law School), the district court’s decision in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, by “focus[ing] on diversity as the sole grounds on which the use of race in admissions may be justified,” avoided “engag[ing] more deeply and directly with the question of whether affirmative action is now merely a tool to promote pluralism or remains an appropriate remedy for longtime systemic, state-sanctioned oppression.”4 This Essay, however, criticizes the district court’s assessment of Harvard’s use of race-based affirmative action at all, given that the lawsuit’s central claim had nothing to do with it. In a footnote, the court addresses the real claim at hand—discrimination against Asian- American applicants vis-à-vis white applicants resulting from race-neutral components of the admissions program.5 Had the analysis in this footnote served as the central basis of the court’s ruling, it could have both * Associate Professor of Law, City University of New York School of Law. -

MS-603: Rabbi Marc H

MS-603: Rabbi Marc H. Tanenbaum Collection, 1945-1992. Series A: Writings and Addresses. 1947-1991 Box 7, Folder 8, Miscellaneous commentaries INC 18-118], Undated. 3101 Clifton Ave , Cincinnati, Ohio 45220 (513) 221·1675 phone. (513) 221·7612 fax americanjewisharchives.org nc. / ~ TITLE OF BOOK (To be Choeen) hy Marc H. Tanen~aum priest's / '. TURNING POINT8 IN JEIHSH_CHRI5TIAN_MU8LIM RELATIONS hi. xxxxxxxxxxxx~xxxx I _ FROM DIMIDIVKA TO VA!ICAN CITY My; first ex?osure to Christiane and to Chr.le,tlan theology "'~ .~Dn . at shout agp. four. In our poer, nevout home '1n .South Baltl111ore ,' it Was a family practice thqt no Sa~~ath aft~rnoon8 my fath~r would Bit with my ~rother, my sister nnd myself and would review with us stories 1n the weekly portlo~ of thp. Bl~le, mixed with rBminiacencea of the lIold countrylt. 8p.fore com1ng to k~r1ca in the early lQ20s, he had 11vena. a child with his family 1n Dlmldlvka, an . 11t;~(J'Verlsh6d J~'i'lRh villAge 1n the Ukraine. On the Snb .... ath "'"fnre Passover. wh~n anticipations ,....f" Passover an1 Easter were 1n the air of Baltimore, our fathp.r felt a compuledlon to un8urden himself with this Btory. It . happi!ned on Good Friday in D1m1d1vka. Down. the mudd~ roan from my father's v 1llaR::8, there 9tood a Ruee1an Ortho(tox ehul"c" During the Good Friday liturgy in wh10h the CD1ro1f1x1nn of Christ Was recounted, the Orthodox pr1eat apparently ~eo9me 80 enraged OVer the role of lithe Jews" as Chr1et-k11lp.rs", that , he worked his co!'gregaUonll of Russian peasant·.