Cold War Gaming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grappling with the Bomb: Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

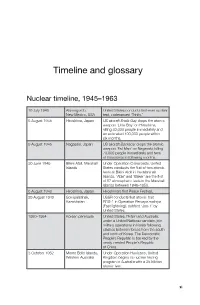

Timeline and glossary Nuclear timeline, 1945–1963 16 July 1945 Alamogordo, United States conducts first-ever nuclear New Mexico, USA test, codenamed ‘Trinity .’ 6 August 1945 Hiroshima, Japan US aircraft Enola Gay drops the atomic weapon ‘Little Boy’ on Hiroshima, killing 80,000 people immediately and an estimated 100,000 people within six months . 9 August 1945 Nagasaki, Japan US aircraft Bockscar drops the atomic weapon ‘Fat Man’ on Nagasaki, killing 70,000 people immediately and tens of thousands in following months . 30 June 1946 Bikini Atoll, Marshall Under Operation Crossroads, United Islands States conducts the first of two atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. ‘Able’ and ‘Baker’ are the first of 67 atmospheric tests in the Marshall Islands between 1946–1958 . 6 August 1948 Hiroshima, Japan Hiroshima’s first Peace Festival. 29 August 1949 Semipalatinsk, USSR conducts first atomic test Kazakhstan RDS-1 in Operation Pervaya molniya (Fast lightning), dubbed ‘Joe-1’ by United States . 1950–1954 Korean peninsula United States, Britain and Australia, under a United Nations mandate, join military operations in Korea following clashes between forces from the south and north of Korea. The Democratic People’s Republic is backed by the newly created People’s Republic of China . 3 October 1952 Monte Bello Islands, Under Operation Hurricane, United Western Australia Kingdom begins its nuclear testing program in Australia with a 25 kiloton atomic test . xi GRAPPLING WITH THE BOMB 1 November 1952 Bikini Atoll, Marshall United States conducts its first Islands hydrogen bomb test, codenamed ‘Mike’ (10 .4 megatons) as part of Operation Ivy . -

SPYCATCHER by PETER WRIGHT with Paul Greengrass WILLIAM

SPYCATCHER by PETER WRIGHT with Paul Greengrass WILLIAM HEINEMANN: AUSTRALIA First published in 1987 by HEINEMANN PUBLISHERS AUSTRALIA (A division of Octopus Publishing Group/Australia Pty Ltd) 85 Abinger Street, Richmond, Victoria, 3121. Copyright (c) 1987 by Peter Wright ISBN 0-85561-166-9 All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. TO MY WIFE LOIS Prologue For years I had wondered what the last day would be like. In January 1976 after two decades in the top echelons of the British Security Service, MI5, it was time to rejoin the real world. I emerged for the final time from Euston Road tube station. The winter sun shone brightly as I made my way down Gower Street toward Trafalgar Square. Fifty yards on I turned into the unmarked entrance to an anonymous office block. Tucked between an art college and a hospital stood the unlikely headquarters of British Counterespionage. I showed my pass to the policeman standing discreetly in the reception alcove and took one of the specially programmed lifts which carry senior officers to the sixth-floor inner sanctum. I walked silently down the corridor to my room next to the Director-General's suite. The offices were quiet. Far below I could hear the rumble of tube trains carrying commuters to the West End. I unlocked my door. In front of me stood the essential tools of the intelligence officer’s trade - a desk, two telephones, one scrambled for outside calls, and to one side a large green metal safe with an oversized combination lock on the front. -

April 19 Digest (Pdf)

Dear all, Please see below for upcoming events, opportunities, and publications that may be of interest to you. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. ‘Invisible Agents’ with Nadine Akkerman 2. ‘Breaking News! US Intelligence and the Press’ 3. ‘The scandalous case of John Vassall’ with Mark Dunton 4. Conference on ‘Women in Intelligence’ 5. Conference on ‘Emerging Trends: New Tools, Threats, and Thinking’ 6. Belgian Intelligence Studies Centre Conference 7. CfP: ‘The Bondian Cold War: The Transitional Legacies of a Cold War Icon’ 8. CfP: ‘Need to Know IX: Intelligence and major political change’ 9. Journal for Intelligence, Propaganda and Security Studies (Vol.12, No.1) 10. International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence (Vol.32, No.1) EVENTS 1.’Invisible Agents’ with Nadine Akkerman Hosted by Edinburgh Spy Week Friday 12 April Project Room, 50 George Square Edinburgh, UK Nadine Akkerman, winner of the 2019 Ammodo Science Award, will discuss her research into the role of women in the politics and espionage of the seventeenth century. For her best-selling book Invisible Agents, Nadine had to act as a modern-day spy, breaking cipher codes and studying invisible inks to unearth long-hidden plots and conspiracies. This compelling and ground-breaking contribution to the history of espionage details a series of case studies in which women - from playwright to postmistress, from lady-in-waiting to laundry woman - acted as spies, sourcing and passing on confidential information on account of political and religious convictions or to obtain money or power. Registration is available here 2. ‘Breaking News! US Intelligence and the Press’ Hosted by the Michael V. -

The Ethics of Intelligence Collection Ross W. Bellaby

What’s the Harm? The Ethics of Intelligence Collection Ross W. Bellaby Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of International Politics Aberystwyth University June 13th, 2011 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed ...................................................................... (Ross W. Bellaby) Date ........................................................................ STATEMENT 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Where *correction services have been used, the extent and nature of the correction is clearly marked in a footnote(s). Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed ..................................................................... (Ross W. Bellaby) Date ........................................................................ [*this refers to the extent to which the text has been corrected by others] STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ..................................................................... (Ross W. Bellaby) Date ........................................................................ I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying -

Downloads of Technical Information

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 Nuclear Spaces: Simulations of Nuclear Warfare in Film, by the Numbers, and on the Atomic Battlefield Donald J. Kinney Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES NUCLEAR SPACES: SIMULATIONS OF NUCLEAR WARFARE IN FILM, BY THE NUMBERS, AND ON THE ATOMIC BATTLEFIELD By DONALD J KINNEY A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Donald J. Kinney defended this dissertation on October 15, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: Ronald E. Doel Professor Directing Dissertation Joseph R. Hellweg University Representative Jonathan A. Grant Committee Member Kristine C. Harper Committee Member Guenter Kurt Piehler Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Morgan, Nala, Sebastian, Eliza, John, James, and Annette, who all took their turns on watch as I worked. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee, Kris Harper, Jonathan Grant, Kurt Piehler, and Joseph Hellweg. I would especially like to thank Ron Doel, without whom none of this would have been possible. It has been a very long road since that afternoon in Powell's City of Books, but Ron made certain that I did not despair. Thank you. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract..............................................................................................................................................................vii 1. -

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: from Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare By

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: From Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare by Matthew A. Bellamy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2018 Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Najita, Chair Professor Daniel Hack Professor Mika Lavaque-Manty Associate Professor Andrea Zemgulys Matthew A. Bellamy [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-6914-8116 © Matthew A. Bellamy 2018 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to all my students, from those in Jacksonville, Florida to those in Port-au-Prince, Haiti and Ann Arbor, Michigan. It is also dedicated to the friends and mentors who have been with me over the seven years of my graduate career. Especially to Charity and Charisse. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication ii List of Figures v Abstract vi Chapter 1 Introduction: Espionage as the Loss of Agency 1 Methodology; or, Why Study Spy Fiction? 3 A Brief Overview of the Entwined Histories of Espionage as a Practice and Espionage as a Cultural Product 20 Chapter Outline: Chapters 2 and 3 31 Chapter Outline: Chapters 4, 5 and 6 40 Chapter 2 The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 1: Conspiracy, Bureaucracy and the Espionage Mindset 52 The SPECTRE of the Many-Headed HYDRA: Conspiracy and the Public’s Experience of Spy Agencies 64 Writing in the Machine: Bureaucracy and Espionage 86 Chapter 3: The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 2: Cruelty and Technophilia -

MARINEMARINE Life the ‘Taking Over the World’ Edition

MARINEMARINE Life The ‘taking over the world’ edition October/November 2012 ISSUE 21 Our Goal To educate, inform, have fun and share our enjoyment of the marine world with like- minded people. FeaturesFeatures andand CreaturesCreatures The Editorial Staff (and the zen bits, grasshopper) Emma Flukes, Co-Editor: Shallow understanding News from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. BREAKING: Super Trawler stopped – a summary of events & YOUR FEEDBACK 1 [I’m definitely not zen enough to understand any National & International Roundup 6 of this, but let’s run with it anyway...] State-by-state: QLD 8 Michael Jacques, Co-Editor: In the practice of WA 10 tolerance, one's enemy is the best teacher. NT 12 NT Honcho – Grant Treloar TAS 13 Tas Honchos - Phil White and Geoff Rollins SA Honcho – Peter Day WA Honcho – Mike Lee Bits & Pieces Federal marine parks cop a roasting 16 Climate change sceptics on the decline – are we finally getting through? 17 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication The imminent future of Wave Energy 18 are not necessarily the views of the editorial staff or Seaweed: the McDonald’s of the Ocean? 20 associates of this publication. We make no promise that any of this will make sense. Ugly animals need loving too! – an experiment in anthropomorphism 21 Feature Stories Cover Photo; Maori Octopus – John Smith Saving the sand of SA beaches (and more about those cuttlefish…) 24 We are now part of the wonderful The Montebello Islands (WA) - A nuclear wilderness 27 world of Facebook! Check us out, stalk our updates, and ‘like’ our Heritage and Coastal Features page to fuel our insatiable egos. -

We Envy No Man on Earth Because We Fly. the Australian Fleet Air

We Envy No Man On Earth Because We Fly. The Australian Fleet Air Arm: A Comparative Operational Study. This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Murdoch University 2016 Sharron Lee Spargo BA (Hons) Murdoch University I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. …………………………………………………………………………….. Abstract This thesis examines a small component of the Australian Navy, the Fleet Air Arm. Naval aviators have been contributing to Australian military history since 1914 but they remain relatively unheard of in the wider community and in some instances, in Australian military circles. Aviation within the maritime environment was, and remains, a versatile weapon in any modern navy but the struggle to initiate an aviation branch within the Royal Australian Navy was a protracted one. Finally coming into existence in 1947, the Australian Fleet Air Arm operated from the largest of all naval vessels in the post battle ship era; aircraft carriers. HMAS Albatross, Sydney, Vengeance and Melbourne carried, operated and fully maintained various fixed-wing aircraft and the naval personnel needed for operational deployments until 1982. These deployments included contributions to national and multinational combat, peacekeeping and humanitarian operations. With the Australian government’s decision not to replace the last of the aging aircraft carriers, HMAS Melbourne, in 1982, the survival of the Australian Fleet Air Arm, and its highly trained personnel, was in grave doubt. This was a major turning point for Australian Naval Aviation; these versatile flyers and the maintenance and technical crews who supported them retrained on rotary aircraft, or helicopters, and adapted to flight operations utilising small compact ships. -

Australian Radiation Laboratory R

AR.L-t*--*«. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. HOUSING & COMMUNITY SERVICES Public Health Impact of Fallout from British Nuclear Weapons Tests in Australia, 1952-1957 by Keith N. Wise and John R. Moroney Australian Radiation Laboratory r. t J: i AUSTRALIAN RADIATION LABORATORY i - PUBLIC HEALTH IMPACT OF FALLOUT FROM BRITISH NUCLEAR WEAPONS TESTS IN AUSTRALIA, 1952-1957 by Keith N Wise and John R Moroney ARL/TR105 • LOWER PLENTY ROAD •1400 YALLAMBIE VIC 3085 MAY 1992 TELEPHONE: 433 2211 FAX (03) 432 1835 % FOREWORD This work was presented to the Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia in 1985, but it was not otherwise reported. The impetus for now making it available to a wider audience came from the recent experience of one of us (KNW)* in surveying current research into modelling the transport of radionuclides in the environment; from this it became evident that the methods we used in 1985 remain the best available for such a problem. The present report is identical to the submission we made to the Royal Commission in 1985. Developments in the meantime do not call for change to the derivation of the radiation doses to the population from the nuclear tests, which is the substance of the report. However the recent upward revision of the risk coefficient for cancer mortality to 0.05 Sv"1 does require a change to the assessment we made of the doses in terms of detriment tc health. In 1985 we used a risk coefficient of 0.01, so that the estimates of cancer mortality given at pages iv & 60, and in Table 7.1, need to be multiplied by five. -

The Civil Defence Hiatus: a Rediscovery of Nuclear Civil Defence Policy 1968-1983

University of Bristol Department of Historical Studies Best undergraduate dissertations of 2009 Rose Farrell The Civil Defence Hiatus: A Rediscovery of Nuclear Civil Defence Policy 1968-1983 PDF processed with CutePDF evaluation edition www.CutePDF.com In June 2009, the Department of Historical Studies at the University of Bristol voted to begin to publish the best of the annual dissertations produced by the department’s 3rd year undergraduates (deemed to be those receiving a mark of 75 or above) in recognition of the excellent research work being undertaken by our students. As a department, we are committed to the advancement of historical knowledge and understanding, and to research of the highest order. We believe that our undergraduates are part of that endeavour. This was one of the best of this year’s 3rd year undergraduate dissertations. Please note: this dissertation is published in the state it was submitted for examination. Thus the author has not been able to correct errors and/or departures from departmental guidelines for the presentation of dissertations (e.g. in the formatting of its footnotes and bibliography). The author, 2009. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means without the prior permission in writing of the author, or as expressly permitted by law. ‘The Civil Defence Hiatus’1 A Rediscovery of Nuclear Civil Defence Policy 1968 - 1983 Candidate Number: 32694 Word Count: 12,082 A dissertation submitted in accordance with the structure of the Historical Studies BA, Bristol University, April 2009 1 Lawrence J. -

WHEN the WIND BLOWS Programme Notes

WHEN THE WIND BLOWS Programme Notes “Is there a clean white shirt, dear? Ready for the bomb?” ‘Protect and Survive’ was published in May 1980. This government pamphlet was designed to provide information to the general public concerning preparation for a nuclear attack on the UK, as well as procedure during the aftermath. The Times newspaper had become aware of the existence of the leaflet in late 1979 and their exposure led to the government making it generally available six months later – it seems that the details contained within may have been intended for police, fire services, and local authorities but an outcry brought the booklet to wider attention. This in turn resulted in criticism from bodies like the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament – proper scrutiny of the guidance revealing at best a naïve outlook, at worst a bid to obfuscate and to misinform the population. Despite this, the government of the day ploughed on, with additional Home Office from Richard Taylor Animation and narrated by Patrick Allen – again, not intended for broadcast until hostilities were deemed imminent, but quickly leaked and revealed by CND and by the BBC current affairs flagship ‘Panorama’. Suitably appalled by the manner in which the official line was deviating from likely reality, the popular artist and children’s illustrator Raymond Briggs published his graphic novel ‘When The Wind Blows’ in response. This 1982 work depicts a retired couple, Jim and Hilda Bloggs, with old-fashioned values, living a gentle everyday existence, and (with talk of conflict rife in the media) discussing their memories of having survived the Second World War. -

Antinuclear Politics, Atomic Culture, and Reagan Era Foreign Policy

Selling the Second Cold War: Antinuclear Cultural Activism and Reagan Era Foreign Policy A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy William M. Knoblauch March 2012 © 2012 William M. Knoblauch. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Selling the Second Cold War: Antinuclear Cultural Activism and Reagan Era Foreign Policy by WILLIAM M. KNOBLAUCH has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by __________________________________ Chester J. Pach Associate Professor of History __________________________________ Howard Dewald Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT KNOBLAUCH, WILLIAM M., Ph.D., March 2012, History Selling the Second Cold War: Antinuclear Cultural Activism and Reagan Era Foreign Policy Director of Dissertation: Chester J. Pach This dissertation examines how 1980s antinuclear activists utilized popular culture to criticize the Reagan administration’s arms buildup. The 1970s and the era of détente marked a decade-long nadir for American antinuclear activism. Ronald Reagan’s rise to the presidency in 1981 helped to usher in the “Second Cold War,” a period of reignited Cold War animosities that rekindled atomic anxiety. As the arms race escalated, antinuclear activism surged. Alongside grassroots movements, such as the nuclear freeze campaign, a unique group of antinuclear activists—including publishers, authors, directors, musicians, scientists, and celebrities—challenged Reagan’s military buildup in American mass media and popular culture. These activists included Fate of the Earth author Jonathan Schell, Day After director Nicholas Meyer, and “nuclear winter” scientific-spokesperson Carl Sagan.