Variants, Including Females (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis Persius Persius

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada ENDANGERED 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 41 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge M.L. Holder for writing the status report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada. COSEWIC also gratefully acknowledges the financial support of Environment Canada. The COSEWIC report review was overseen and edited by Theresa B. Fowler, Co-chair, COSEWIC Arthropods Species Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur l’Hespérie Persius de l’Est (Erynnis persius persius) au Canada. Cover illustration: Eastern Persius Duskywing — Original drawing by Andrea Kingsley ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2006 Catalogue No. CW69-14/475-2006E-PDF ISBN 0-662-43258-4 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – April 2006 Common name Eastern Persius Duskywing Scientific name Erynnis persius persius Status Endangered Reason for designation This lupine-feeding butterfly has been confirmed from only two sites in Canada. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Matthew P. Ayres

CURRICULUM VITAE Matthew P. Ayres Department of Biological Sciences, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH 03755 (603) 646-2788, [email protected], http://www.dartmouth.edu/~mpayres APPOINTMENTS Professor of Biological Sciences, Dartmouth College, 2008 - Associate Director, Institute of Arctic Studies, Dartmouth College, 2014 - Associate Professor of Biological Sciences, Dartmouth College, 2000-2008 Assistant Professor of Biological Sciences, Dartmouth College, 1993 to 2000 Research Entomologist, USDA Forest Service, Research Entomologist, 1993 EDUCATION 1991 Ph.D. Entomology, Michigan State University 1986 Fulbright Fellowship, University of Turku, Finland 1985 M.S. Biology, University of Alaska Fairbanks 1983 B.S. Biology, University of Alaska Fairbanks PROFESSIONAL AFFILIATIONS Ecological Society of America Entomological Society of America PROFESSIONAL SERVICES Member, Board of Editors: Ecological Applications; Member, Editorial Board, Population Ecology Referee: (10-15 manuscripts / year) American Naturalist, Annales Zoologici Fennici, Bioscience, Canadian Entomologist, Canadian Journal of Botany, Canadian Journal of Forest Research, Climatic Change, Ecography, Ecology, Ecology Letters, Ecological Entomology, Ecological Modeling, Ecoscience, Environmental Entomology, Environmental & Experimental Botany, European Journal of Entomology, Field Crops Research, Forest Science, Functional Ecology, Global Change Biology, Journal of Applied Ecology, Journal of Biogeography, Journal of Geophysical Research - Biogeosciences, Journal of Economic -

“Thermal Time” Constraints in Papilio: Latitudinal and Local Size Clines Differ in Response to Regional Climate Change

Insects 2014, 5, 199-226; doi:10.3390/insects5010199 OPEN ACCESS insects ISSN 2075-4450 www.mdpi.com/journal/insects/ Article Adaptations to “Thermal Time” Constraints in Papilio: Latitudinal and Local Size Clines Differ in Response to Regional Climate Change J. Mark Scriber *, Ben Elliot, Emily Maher, Molly McGuire and Marjie Niblack Department of Entomology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (B.E.); [email protected] (E.M.); [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (M.N.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]. Received: 22 October 2013; in revised form: 20 December 2013 / Accepted: 8 January 2014 / Published: 21 January 2014 Abstract: Adaptations to “thermal time” (=Degree-day) constraints on developmental rates and voltinism for North American tiger swallowtail butterflies involve most life stages, and at higher latitudes include: smaller pupae/adults; larger eggs; oviposition on most nutritious larval host plants; earlier spring adult emergences; faster larval growth and shorter molting durations at lower temperatures. Here we report on forewing sizes through 30 years for both the northern univoltine P. canadensis (with obligate diapause) from the Great Lakes historical hybrid zone northward to central Alaska (65° N latitude), and the multivoltine, P. glaucus from this hybrid zone southward to central Florida (27° N latitude). Despite recent climate warming, no increases in mean forewing lengths of P. glaucus were observed at any major collection location (FL to MI) from the 1980s to 2013 across this long latitudinal transect (which reflects the “converse of Bergmann’s size Rule”, with smaller females at higher latitudes). -

Latitudinal and Local Geographic Mosaics in Host Plant Preferences As Shaped by Thermal Units and Voltinism Papilioin Spp

Eur. J. Entomol. 99: 225-239, 2002 ISSN 1210-5759 Latitudinal and local geographic mosaics in host plant preferences as shaped by thermal units and voltinism Papilioin spp. (Lepidoptera) J. Mark SCRIBER Department ofEntomology, Michigan State University, 47 Natural Science Building, East Lansing, MI 48824-1115, USA; e-mail: [email protected] Key words. Butterflies, climate warming, degree days, diapause, “false-second” generation, introgression, oviposition preferences, Papilio glaucus, P. canadensis, North America, reproductive isolation, sex-linkage Abstract. Laboratory and field tests support the “voltinism-suitability hypothesis” of host selection at various latitudes as well as in local “cold pockets”: The best hosts for rapid development will be selected by herbivorous insects under severe thermal constraints for completion of the generation before winter. Papilio canadensis and P. glaucus females do select the best hosts for rapid larval growth in Alaska and in southern Michigan, but not in northern Michigan and southern Ohio. In addition to latitudinal patterns, local host preferences of P. canadensis are described in relation to “phenological twisting” of leaf suitability for larval growth in cold pockets with “thermally constrained” growing season lengths. White ash leaves ( Fraxinus americana) have the highest nutritional quality (relative to cherry, aspen, birch, and other local trees) throughout June and July for P. canadensis populations inside the cold pocket, but not outside. In all areas outside the cold pockets, even with bud-break occurring much later than other tree species, ash leaves rapidly decline in quality after mid-June and become one of the worse tree host species for larvae. This temperature-driven phenology difference creates a geographic mosaic in host plant suitability for herbivores. -

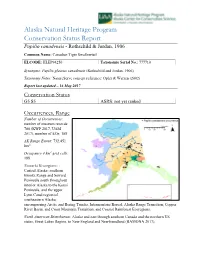

Alaska Natural Heritage Program Conservation Status Report

Alaska Natural Heritage Program Conservation Status Report Papilio canadensis - Rothschild & Jordan, 1906 Common Name: Canadian Tiger Swallowtail ELCODE: IILEP94250 Taxonomic Serial No.: 777710 Synonyms: Papilio glaucus canadensis (Rothschild and Jordan, 1906) Taxonomy Notes: NatureServe concept reference: Opler & Warren (2002). Report last updated – 16 May 2017 Conservation Status G5 S5 ASRS: not yet ranked Occurrences, Range Number of Occurrences: number of museum records: 786 (KWP 2017, UAM 2017), number of EOs: 188 AK Range Extent: 732,451 km2 Occupancy 4 km2 grid cells: 188 Nowacki Ecoregions: : Central Alaska: southern Brooks Range and Seward Peninsula south throughout interior Alaska to the Kenai Peninsula, and the upper Lynn Canal region of southeastern Alaska; encompassing Arctic and Bering Tundra, Intermontane Boreal, Alaska Range Transition, Copper River Basin, and Coast Mountain Transition, and Coastal Rainforest Ecoregions. North American Distribution: Alaska and east through southern Canada and the northern US states, Great Lakes Region, to New England and Newfoundland (BAMONA 2017). Trends Short-term: Proportion collected has remained stable (<10% change). Long-term: There was a peak in collection proportion during the 1950s, however the proportion collected has remained stable (<10% change) since the 1960’s. The peak in collection proportion during the 1910’s is due to a limited specimen total of two, therefore the proportion is artificially inflated. Papilio canadensis Collections in Alaska 350 60 300 50 250 40 200 30 150 20 100 50 10 Percent of Museum Collections Numberof Museum Collections 0 0 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 Collections by Decade P. canadensis P. canadensis Proportion Threats Scope and Severity: Most threats (including development, pollution, biological resource use, etc.) are anticipated to be negligible in scope and unknown in severity. -

Differential Antennal Sensitivities of the Generalist Butterflies Papilio Glaucus and P

8484 JOURNAL OF THE LEPIDOPTERISTS’ SOCIETY Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society 62(2), 2008, 84-88 DIFFERENTIAL ANTENNAL SENSITIVITIES OF THE GENERALIST BUTTERFLIES PAPILIO GLAUCUS AND P. CANADENSIS TO HOST PLANT AND NON-HOST PLANT EXTRACTS R. J. MERCADER Department of Entomology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA; email: [email protected], L. L. STELINSKI Entomology and Nematology Department, University of Florida, Citrus Research and Education Center, 700 Experiment Station Road, Lake Alfred, FL 33850, USA, AND J. M. SCRIBER Department of Entomology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA. ABSTRACT. It is likely that olfaction is used by some generalist insect species as a pre-alighting cue to ameliorate the costs of foraging for suitable hosts. In which case, significantly higher antennal sensitivity would be expected to the volatiles of preferred over less or non-preferred host plants. To test this hypothesis, antennal sensitivity was measured by recording electroantennogram (EAG) responses from intact antennae of the generalists Papilio glaucus L. and P. canadensis R & J (Papilionidae) to methanolic leaf extracts of primary, secondary, and non-host plants. EAGs recorded from antennae of P. glaucus were approximately four fold higher than those of P. canadensis in response to extracts of its most suitable host plant, Liriodendron tulipifera (Magnoliaceae). Likewise, EAG responses of P. canandensis to its preferred host, Populus tremu- loides (Salicaceae), were significantly higher than those of P. glaucus. In addition, P. glaucus exhibited significantly higher (approximately three fold) EAG responses to its preferred host, L. tulipifera, than to its less-preferred hosts, Ptelea trifoliata, Sassafras albidum, and Lindera ben- zoin. -

Lepidoptera: Papilionidae)

The Great Lakes Entomologist Volume 31 Number 2 - Summer 1998 Number 2 - Summer Article 4 1998 June 1998 The Inheritance of Diagnostic Larval Traits for Interspecific Hybrids of Papilio Canadensis and P. Glaucus (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae) J. Mark Scriber Michigan State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Scriber, J. Mark 1998. "The Inheritance of Diagnostic Larval Traits for Interspecific Hybrids of Papilio Canadensis and P. Glaucus (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae)," The Great Lakes Entomologist, vol 31 (2) Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle/vol31/iss2/4 This Peer-Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Great Lakes Entomologist by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Scriber: The Inheritance of Diagnostic Larval Traits for Interspecific Hyb 1998 THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOlOGIST 113 THE INHERITANCE OF DIAGNOSTIC LARVAL TRAITS FOR INTERSPECIFIC HYBRIDS OF PAPILIO CANADENSIS AND P. GLAUCUS (LEPIDOPTERA: PAPIUONIDAE) 1. Mark Scriberl ABSTRACT Traits distinguishing the closely related tiger swallowtail butterfly species, Papilio canadensis and P. glaucus, include fixed differences in diag nostic sex-linked and autosomal allozymes as well as sex-linked diapause regulation, and sex-linked differences in oviposition behavior. Larval detoxi fication abilities for plants of the Salicaceae and Magnoliaceae families are dramatically different and basically diagnostic as well. The distinguisbing morphological traits of the adults and larvae have not been genetically char acterized. Here we describe the segregation of diagnostic larval banding traits in offspring from the 2 species in their hybrid and reciprocal backcross combinations. -

Papilio Canadensis and P. Glaucus (Papilionidae)

JOURNAL OF THE LEPIDOPTERISTS' SOCIETY Volume 45 1991 Number 4 Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 45(4), 1991, 245-258 PAPILlO CANADENSIS AND p, GLAUCUS (PAPILIONIDAE) ARE DISTINCT SPECIES ROBERT H. HAGEN,! ROBERT C. LEDERHOUSE, J. L. BOSSART AND J. MARK SCRIBER Department of Entomology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48824 ABSTRACT. Papilio canadensis Rothschild & Jordan is recognized as a distinct spe cies, not a subspecies of P. glaucus L., on the basis of physiological and genetic differences despite great similarity in adult appearance of these two taxa. Interspecific hybrids are found in a well-marked zone where the ranges of the species come into contact. The ecological or genetic factors that maintain species integrity despite this natural hybrid ization are as yet uncertain. Additional key words: diapause, electrophoresis, hybrid zone, Michigan, Great Lakes region. In their revision of American Papilionidae, Rothschild and Jordan (1906) described a northern subspecies of Papilio glaucus L., P. g. canadensis, distinguishable from P. g. glaucus by differences in the details of wing color pattern and by its smaller size. Although evidence was scanty, Rothschild and Jordan suggested that glaucus and cana densis "com pletely intergrade" in the Great Lakes region. Presumably, the parapatric distribution of these two taxa was a major factor in their decision to treat canadensis as a subspecies of P. glaucus. Despite the morphological similarity between P. glaucus and can adensis adults and the occurrence of natural hybridization, our recent studies lead us to conclude that canadensis does warrant recognition as a distinct species. Three lines of evidence support our interpretation: first, there is significant differentiation between glaucus and canadensis in characters besides adult morphology; second, there appears to be a closer phylogenetic relationship between glaucus and P. -

Sentinels on the Wing: the Status and Conservation of Butterflies in Canada

Sentinels on the Wing The Status and Conservation of Butterflies in Canada Peter W. Hall Foreword In Canada, our ties to the land are strong and deep. Whether we have viewed the coasts of British Columbia or Cape Breton, experienced the beauty of the Arctic tundra, paddled on rivers through our sweeping boreal forests, heard the wind in the prairies, watched caribou swim the rivers of northern Labrador, or searched for song birds in the hardwood forests of south eastern Canada, we all call Canada our home and native land. Perhaps because Canada’s landscapes are extensive and cover a broad range of diverse natural systems, it is easy for us to assume the health of our important natural spaces and the species they contain. Our country seems so vast compared to the number of Canadians that it is difficult for us to imagine humans could have any lasting effect on nature. Yet emerging science demonstrates that our natural systems and the species they contain are increas- ingly at risk. While the story is by no means complete, key indicator species demonstrate that Canada’s natural legacy is under pressure from a number of sources, such as the conversion of lands for human uses, the release of toxic chemicals, the introduction of new, invasive species or the further spread of natural pests, and a rapidly changing climate. These changes are hitting home and, with the globalization and expansion of human activities, it is clear the pace of change is accelerating. While their flights of fancy may seem insignificant, butterflies are sentinels or early indicators of this change, and can act as important messengers to raise awareness. -

On Ontario Tiger Swallowtails B

MORE ON ONTARIO TIGER SWALLOWTAILS B. Christian Schmidt Two species of tiger swallowtails, Canadian (Papilio canadensis) and Eastern (P. glaucus), are typically depicted as occurring in Ontario. However, the exact distribution, identification and supposed hybridization between the two blur the lines between who’s who. A summer-flying glaucus-like swallowtail that may be a hybrid between P. canadensis and P. glaucus occurs throughout most of eastern Ontario. This situation was recently reviewed by Wang (TEA, Ontario Lepidoptera 2017). The purpose of this note is to provide further information on the distribution and identification of Ontario’s tiger swallowtails, and to identify knowledge gaps that butterfly enthusiasts can help fill in. It is hoped that this will raise awareness of the fact that there are still considerable research needs among the most conspicuous of all Canadian butterflies. The database of the Ontario Butterfly Atlas (Macnaughton et al. 2018) was used to generate distribution maps, phenologies, and to re-examine species identifications. The Papilio glaucus species group has a long history of changing species concepts – prior to 1991, only one species was recognized and the Canadian Tiger Swallowtail (P. canadensis) was thought to be a subspecies of the larger, more southerly P. glaucus. But mounting evidence from many aspects of developmental biology, biochemistry and morphology showed that P. canadensis was in fact a separate species (Hagen et al. 1991). Much of what we know about the evolution of the Papilio glaucus group stems from over three decades of research by Mark Scriber and collaborators. Surprises continue: recently, the discovery of a new species in the Appalachian Mountains, Papilio appalachiensis, has sparked further research into species boundaries within tiger swallowtails, particularly the nature and role of hybridization in speciation. -

Tesar, D., and J. M. Scriber

Vol. 7 No. 2 2000 TESAR and SCRIBER: Growth Season Constraints for Swallowtail Larvae 39 HOLARCTIC LEPIDOPTERA, 7(2): 39-44 (2003) GROWTH SEASON CONSTRAINTS IN CLIMATIC COLD POCKETS: TOLERANCE OF SUBFREEZING TEMPERATURES AND COMPENSATORY GROWTH BY TIGER SWALLOWTAIL BUTTERFLY LARVAE (LEPIDOPTERA: PAPILIONIDAE) DAVID TESAR1 AND J. MARK SCRIBER Dept. of Entomology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48824, USA ABSTRACT.- The combination of limited seasonal thermal unit accumulations (degree days) and freezing mortality or non-freezing cryoinjury from late spring/early fall freezes in climatically constrained areas has been hypothesized to be major determining factors for geographic range limits and degree of polyphagy in herbivorous insects. We test the hypothesis that cold stress such as from sudden freezes has direct or indirect (delayed) negative impact on egg and larval survival and growth of tiger swallowtail butterflies, Papilio glaucus Linnaeus. Nine treatment regimes with three temperatures (-14°C, -8°C, 4°C) and three exposure durations (8h, 24h. or 48h) were tested using 14 different butterfly families. Negative effects were observed for egg viability, 1st instar, 2nd instar, 3rd instar larval survival and growth subsequent to cold treatments, with more serious impact at colder temperatures and longer durations. These results support the hypothesis that, if severe, late spring freezes can select strongly against these vulnerable, non-diapausing stages. However, numerous physiological and ecological adaptations are known to exist for Papilio eggs, larvae, and pupae, which maximize successful completion of the generation before winter. A new one reported here is faster subsequent growth rates in surviving larvae which were exposed to the cold stress for the longest duration. -

NAME of SPECIES: Lymantria Dispar (Linnaeus)

NAME OF SPECIES: Lymantria dispar (Linnaeus) Synonyms: Porthetria dispar (Linnaeus) Common Name: European gypsy moth A. CURRENT STATUS AND DISTRIBUTION I. In Wisconsin? 1. YES X NO 2. Abundance: 42 Counties under quarantine 3. Geographic Range: Counties in the west-central part of the state represent the leading edge of the gypsy moth's westward migration and have scattered populations of the insect. 4. Habitat Invaded: Natural forests, riparian zones, urban areas 5. Historical Status and Rate of Spread in Wisconsin: Entered Wisconsin in the late 1980s. Without the STS aerial spray treatments done each spring in the STS zone, all of Wisconsin would be infested with gypsy moth is less than 15 years. With the spray treatments, that won’t happen for 40 years or more. 6. Proportion of potential range occupied: Eastern half of WI II. Invasive in Similar Climate YES X NO Zones United States: Connecticut, the District of Columbia, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont, parts of Illinois, Indiana, Maine, Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio, Virginia, West Virginia Canada: British Columbia, Nova Scotia Ontario, Quebec III. Invasive in Similar Habitat YES X NO Types IV. Habitat Affected 1. Host plants: Over 500 species of trees and shrubs. Preferred: Oak, aspen, willow, apple, crabapple, tamarack, white birch, witch hazel, mountain ash, basswood, linden, pine (older caterpillars), spruce (older caterpillars) Acceptable: maple, walnut, chestnut, hickory, cherry, hemlock, elm, hackberry, black and yellow birch, beech, cottonwood, box elder, ironwood In WI, hardwoods cover approximately 84% total timberland of three main forest types: Maple/Basswood (5.3 million acres), Aspen/Birch (3.4 million acres), Oak/Hickory (2.9 million acres) 2.